When playwright Mashuq Mushtaq Deen resigned from his residency at New Dramatists in August 2022 and published an open letter on his website explaining the reason for his decision, he expressed hope that his experience would serve as a cautionary tale for the larger theatre community, and that talking about it might prevent similar harm from happening to someone else. He was less interested in retribution or restitution than in healing, and it is in that same spirit that we’ve examined the conflict that began at New Dramatists, a nonprofit playwriting development center located in midtown Manhattan, two years ago.

What we found is one example of what might be considered an endemic breakdown in communication—the kind that has long happened around policy and power dynamics in the theatre, and which in recent years has been coming to light with more urgency.

It was during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout period in early March 2021 that Governor Cuomo’s office released a timeline for New York’s vaccine distribution, which included these eligibility guidelines: “Public-facing government and public employees, not-for-profit workers who provide public-facing services to New Yorkers in need, and essential in-person public-facing building service workers” would be eligible for vaccine appointments beginning March 17. The announcement continued, “This includes workers such as public works employees, social service and child service caseworkers, government inspectors, sanitation workers, DMV workers, County Clerks, building service workers, and election workers—the everyday heroes who have been showing up day in and day out throughout this pandemic.”

There was some debate about whether theatre workers could be considered public-facing employees for eligibility purposes, especially with many of the city’s arts organizations still shuttered or functioning remotely during this time, and the field was desperate to get back to work in person. I surveyed NYC arts orgs about their policies around this rollout, and of the 21 who responded, 14 reported that they did provide letters of vaccine eligibility to employees, while 7 reported they did not. New Dramatists was among the latter group.

ND artistic director Emily Morse said she recalled hearing conflicting reports about whether theatre workers were eligible, but ultimately the message she took away most strongly was that vaccine priority was for “public facing not-for-profits serving New Yorkers in need. At that moment, with what felt like the urgency and scarcity of those potential vaccines, they were allocated for people who were doing the public-facing work for New Yorkers. We did not meet those guidelines. We were not doing public-facing work at that time.”

ND staff and board sought further guidance from local government contacts and received the concise response, “Anyone who works for a nonprofit and interfaces with the public is eligible.” That language sounds simple enough, but ND finance director Christie Brown said they found it “super vague.” As a development laboratory, New Dramatists has nine core employees and a company of approximately 60 resident playwrights, both local and national, including two Princess Grace fellows. The organization does not produce a staged season or sell tickets to the general public, though the company does host programming for residents, including readings, workshops, and meetings—all of which were being held virtually at that time. Another complicating factor: Resident playwrights are considered beneficiaries of ND resources, not year-round employees, and are paid only when they do extended workshops, which made the term “worker” challenging to define.

After fielding many questions regarding eligibility, the ND staff ultimately came to the decision that they would not provide vaccine eligibility letters to all 60 resident playwrights, but would advise recent temporary employees—those who received a 1099 or W2 from 2020 or had a 2021 paystub—to use those documents as proof of employment by a New York nonprofit, and would provide letters of employment verification if requested. But ND did not broadcast this decision widely to its resident writers, and this didn’t sit well with Deen, he explained in a Zoom interview earlier this year.

“There were theatres that proactively said, ‘We want to help you. We are talking to the city government, we are writing you letters. If you want a letter, let us know, we’ll give you one.’”

Deen reportedly received such a letter from Ma-Yi Theater Company, and later that month, in any case, all New Yorkers aged 30 and older became eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine. That would have been the end of the matter—except that along the way, New Dramatists’ decision about vaccine eligibility letters, and the way the org chose to communicate with writers about it, became concerning for some residents, including Deen, who was serving on the Writers Executive Committee and the board of directors at the time. The conflict only escalated from there.

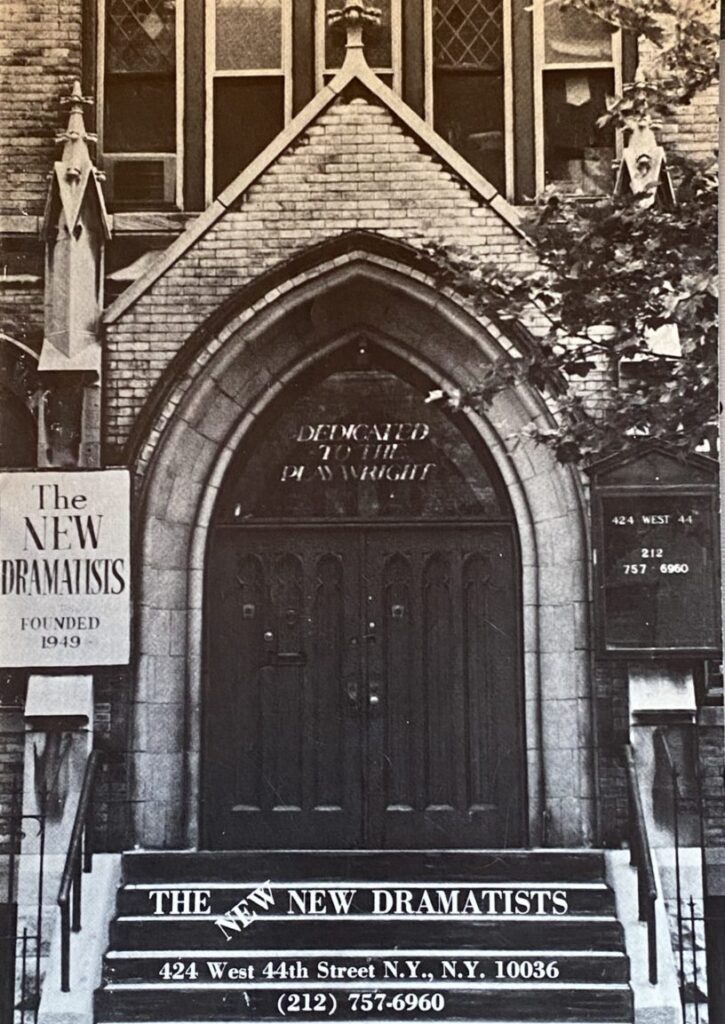

A bit of background on New Dramatists: Founded by playwright Michaela O’Harra in 1949 as “a community where playwrights of diverse aesthetics and backgrounds could develop their plays, share resources, and advocate for themselves and their work in the American theatre,” the organization has nurtured a long list of notable alumni among the 700-plus writers it’s served, and has been regarded as a kind of spiritual home for artists. “It’s a nexus, essentially, certainly of New York theatre, but also of the American theatre,” explained Morse.

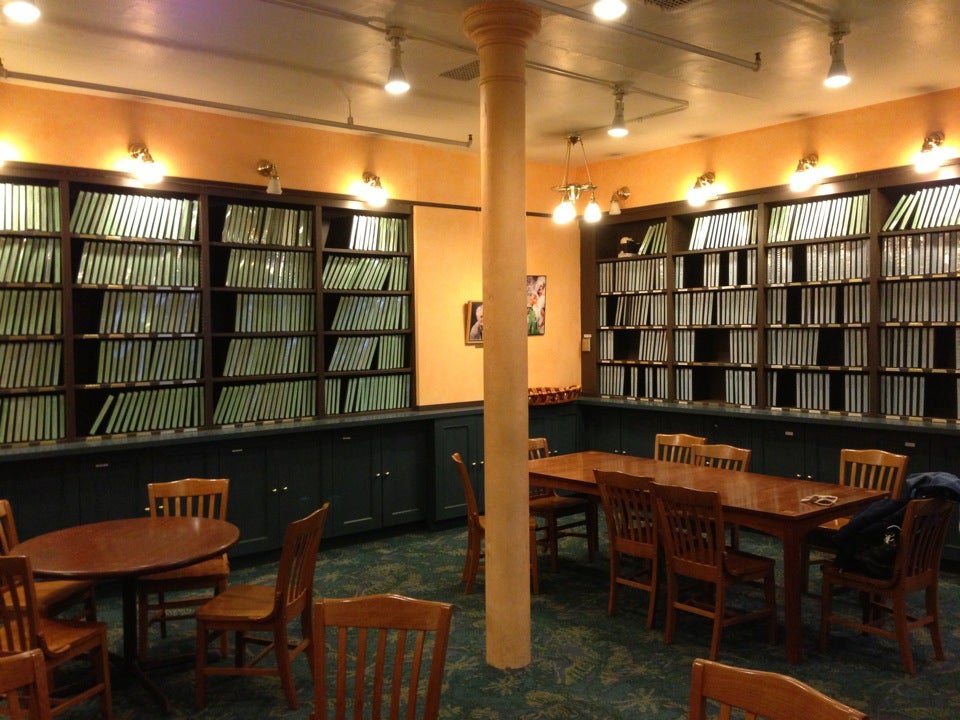

Based out of a 110-year-old Lutheran-mission-turned-arts-center located at 424 West 44th St. between 9th and 10th avenues, the New Dramatists building was a functioning mission up until the late ’60s, and still features most of the same architecture and stained glass as its predecessor. Writers refer to it informally as “the Church.” The building features a library filled with manuscripts, three meeting spaces, a pantry, staff offices, a classroom, a ground-floor studio space, and a theatre on the second floor, where church services were once held. On the third floor is Seventh Heaven, a few modest garrets where writers could stay overnight.

“So much of it was the flow of people,” said one resident playwright of the space’s magnetism. “There were always residents, community members, staff, and other writers who were in the library, who were working, who were at the events, or just moving around the space at any time. Whenever I walked in, I felt I was always welcomed and I felt like I was home.”

“It’s an incredibly crucial resource,” said another resident, “whether you live in the city and you need space to write and get away from home and the people that you live with, or whether you’re a playwright from out of town that needs to come into New York to workshop material.”

The core of ND’s offerings is a free seven-year residency for selected playwrights, who are empowered as the “artistic director” of their own new-play development process.

“I think this idea of being very actively involved in crafting our residencies really felt like a collaborative, collective discussion with staff and resident playwrights,” said one playwright. “Even though they’re staff and we’re resident playwrights, it seemed like the approach was to all be in this together; we all wanted to build and care for this thing that we love.”

A handful of new residents are accepted annually, and the seven-person admissions panel changes over every year. During the pandemic closure, residents were given two bonus years to compensate for the downtime, so many are now on a nine-year track. That was the case with Deen, who was near the end of his 7-year term when he resigned last year.

Playwrights typically apply multiple times before being accepted, and the residency is a meaningful achievement. A few playwrights even recalled bursting into tears or falling over when they learned of their acceptances.

“I applied many times, probably as many as seven, maybe more, before I got in,” said one resident. “It was a real honor and a surprise when I finally got accepted into the community.”

“It’s an extended investment of time,” said Morse, “and each writer then engages in their own artistic investigation over the course of those seven years.” O’Harra’s founding vision, Morse said, was “really about a community of writers, and so the program we offer is both the seven-year residency and the community of peer writers that come with that. So they’re working on their own work, directing their own trajectory through the seven years, but they’re doing it in the company of other artists doing the same, on their own terms. We meet each writer where they are when they come in for their residency.”

New Dramatists’ organizational structure comprises the staff, the board, and the company of playwrights. Within that company is the volunteer Writers Executive Committee (WEC), which gives feedback on organizational matters and plans two annual all-writers meetings. Four playwrights from the WEC also serve as representatives on the board and its various committees, including Deen at the time.

While the resident company has primary authority over their artistic pursuits, they are less involved in the organization’s business practices and day-to-day decision-making. Some resident playwrights consider this a problem, as ND was originally designed to be run by writers, for writers; many feel that their sphere of influence has shrunk in recent years.

“The vibe feels different,” observed one playwright. “It felt before to me that we were a community of artists. The staff were very kind and were there to support our work as artists, and we were all a community. There’s now a separation between leadership, staff, board, and us.”

Said another playwright, “The board has been lumped into being part of the quote-unquote community,” and it hasn’t been a natural fit. Not everyone on the board makes theatre or has lived on a playwright’s income, and some residents suggest that this creates a knowledge gap—which echoes an ongoing conversation about board leadership in the industry.

This cultural gap would lead to further divisions as the pandemic and the racial reckoning of 2020 impacted the field. In June 2020, after New Dramatists put out a statement in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, the organization made a commitment to interrogating its practices, and the board elected to form an Equity, Diversity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (EDAI) Task Force. Deen was invited to join. He “felt like a natural fit,” said Morse, “because of his knowledge base, his experience, and his involvement with the organization.”

It was as a member of that task force that Deen, along with a few other playwrights, expressed concerns via email about New Dramatists’ decision regarding vaccine eligibility letters. Finding the organization’s explanations insufficient, they then asked to discuss the decision at the April WEC meeting.

“There was a very clear concern about our decision making,” said Morse of the email exchange with Deen. “What was at the heart of it evolved through the course of a discussion, and there was a moment where the homogeneity of the decision makers was raised.”

As Deen put it, “I raised the following equity observation: The three staff members who made the decision on [the vaccine eligibility letters] were homogeneous: They were white, lived outside of NYC, lived with other people, and had cars.”

At the Writers Executive Committee meeting on April 22, Deen and other writers spoke about the lack of transparency and communication surrounding the decision. In his open letter, Deen noted that while he “made a point to acknowledge the integrity of all the staff members involved,” he also “brought up the possibility that decision makers of a different demographic might have decided differently. When I raised this equity issue, I advocated only for this: Going forward, can we include more diverse voices in the conversation before decisions are made?” He added, in a significant parenthetical: “The playwright body is the most diverse arm of the organization, as opposed to the staff and board, which are primarily white, and yet we have the least say in what happens organizationally.”

As Deen told me, “It was an example to say, ‘Look, if we’re going down this road of equity, inclusion, and diversity, this is a very clear example of where this group of people does not have enough input or a decision does not include their perspective. So how do we bridge that gap a little bit next time?’”

Morse said she registered the “disappointment that we didn’t make a different decision,” and that “the commitment was to proceed with more transparency around not just how decisions were being made, but also who makes those decisions.”

A month later, things turned sour when Deen said he reached out to executive director Joel Ruark. It became clear that Ruark had been offended by the way Deen had voiced his concerns. “He told me over the phone that he and his wife had revoked their personal friendship from me,” Deen said. It was a difficult remark to hear from a friend—and a complicated one to digest coming from an executive director. (Ruark did not respond to requests for comment.)

“We like to pretend that there are no power dynamics going on,” said Deen. “I think that the blurriness of our arts organizations comes from the fact that we are friends and colleagues. But if you are the artistic director or the executive director, you have power in this organization, and I am dependent on you to support my work out in the field, for you to say nice things about me to other people.”

Observed another resident playwright, “Theatre is this very intimate art form. What does it mean when, within this art form that seems to traffic in trust and intimacy and a lot of dissolving of certain boundaries that other places don’t, someone says, ‘I don’t want to be your friend’?”

Deen assumed that the New Dramatists community was operating from a place of shared understanding, but soon discovered that they were not all on the same page.

“During the pandemic, I think people wanted to be able to say, ‘I am working to take care of this community that is entrusted to me, I know what I’m doing. I’m the executive director,’” said Deen. “For me to challenge that was probably a really difficult thing for [Joel] to hear—that the decision he thought was best might not have been taking into account other points of view.”

Deen reached out to a subset of the WEC explaining his conflict with Ruark and asking for their support. He was concerned that the personal fallout he experienced would discourage others from speaking up about equity issues to the mostly white board and staff, and further worried that the conflict would affect his residency.

“ND can’t respond to EDI issues in this way,” he wrote. “It’s not good for the organization.”

A group of resident playwrights then drafted a statement, which was read at the WEC meeting in June 2021. It identified four key considerations: “1) How a playwright might raise an EDI concern in a way that feels safe. 2) How to make sure there are no punitive responses for raising that concern, not from an individual nor from inadvertent default structures—or lack thereof. 3) How to build and maintain transparency about an EDI process, and ensure follow-up. 4) How to implement an EDI process that supports playwrights and staff; this stuff is hard to raise and it’s hard to hear.”

The playwrights then requested an outside facilitator who could both guide Deen through this personal conflict and provide tools and training for the organization. New Dramatists denied the request. Morse explained, “The Writers Exec is part of the organization, so if things are raised in the Writers Exec, they include the other members of the organization—it is not a playwrights-only space. When something is raised there, it is attended to at the organizational level.”

At this point, there was a shift in the conversation. According to staff, specific language in the playwrights’ statement, such as concerns regarding safety and punitive consequences, as well as the fact that it was read in an open forum, meant that an internal discrimination investigation would be required. Deen received an email from Morse stating that the matter had been referred to the HR Task Force, whose members included three board members, as well as staff members Emily Morse, Joel Ruark, and Christie Brown. The staff members recused themselves from the task force in this case to avoid potential conflicts of interest. The HR review sought to determine whether Deen had been discriminated against, and whether he had suffered professional punitive consequences as a result.

“Any issue that carries the particular weight of potential discrimination or retaliation, and we’re talking about a staff member and a leader of the organization and a main beneficiary, carries real weight on it,” said Brown, who also manages New Dramatists’ HR procedures. “It was not just that this particular subject was brought up, but the way in which it was brought up. When something is said with 13 writers and the whole staff present that has that kind of information or statement in it—to me, as the HR person for New Dramatists, that’s the equivalent of someone telling me, ‘Maybe there’s a fire in the building. I think I see smoke on the third floor.’ We need to find out if there’s something there we need to be concerned about as an organization.”

But Deen and his colleagues weren’t asking for an HR process or an investigation. In an email cc’ing a number of playwrights, he again asked to address the issue as a community and reiterated the request for a facilitator.

I spoke with two facilitators at artEquity, an California-based nonprofit that offers training and consulting services at the intersection of art and activism, to shed some light on this kind of disconnect.

“I’ve seen instances where HR departments are really accessible, really open, and can be really effective,” said Carmen Morgan, artEquity’s founder and executive director. Other times, though, “the lack of trust that the staff has for them makes people feel more comfortable working with an outside third party. Those HR departments are a part of the [organizational] culture, so sometimes folks do feel safer with an outside neutral party. I think that facilitation is a good investment, when you think about the fact that it might stave off litigation or a discrimination investigation, or people leaving.”

For their part, ND’s leaders emphasized the necessity of the internal HR review and insisted on confidentiality for the process. Playwrights were asked not to discuss the situation on the online listserv, as the space included staff members, one of whom was under review. “It was a direction to move the conversation, not to stop the conversation,” said Morse.

Added Brown, “That comes to the heart of how you conduct a review like this. Confidentiality and privacy are really observed to the degree it’s possible. Whenever a workplace issue occurs, small or large, it is not easy to talk about it. It involves people making mistakes, maybe involves people behaving badly, and sharing that information can be or feel scary. For folks to feel comfortable coming forward, they need to know and trust that when they come and share this information, that information is going to be held in close confidence. I prefer to describe it as holding confidence, as opposed to something that feels like you’re keeping a secret.”

But Deen began to feel isolated and unsettled by the process unfolding around him. It seemed to him that New Dramatists staff and members of the community stopped speaking to him. Replies felt distant and overly formal. The few who reached out did so privately.

“When people stop talking to you, it’s a punishing thing, whether or not it’s intended that way,” said Deen. “You don’t understand why a mentor or friend has now suddenly stopped talking to you.”

ND has a standing relationship of pro bono consultation with an attorney on a number of areas, including employment law and pandemic regulations. Deen was informed that the HR Task Force had consulted with an attorney during their investigation. This only compounded his fears, as he did not have the same access to legal advice without involving Legal Aid.

“Is this the way we want institutions to run?” Deen asked. “I think it’s embedded in the corporate structure. I kept thinking, ‘Oh, I’m the glitch in the system. I’m not supposed to say anything. I’m the problem.’ This corporate system is made so that we start an investigation, everyone becomes very silent about what’s happening, no one talks to anyone, and then you’re having an internal investigation into a guy you’ve known for 30 years, who you all know and love dearly, and hasn’t even filed a complaint. How is this even a normal possibility?”

Of course, recent years have been anything but normal. As a New York-based playwright who made a home at New Dramatists during the pre-pandemic years, Deen was used to spending a lot of time at “the Church” chatting with interns, talking to staff, connecting with other writers, and seeing how everyone was doing. Those day-to-day interactions were limited when New Dramatists shifted to virtual programming during the height of the pandemic.

One resident playwright characterized the whole conflict as “a really tragic misunderstanding on Deen’s part, exacerbated by the isolation of the pandemic, not being able to talk face to face, the weird bureaucracy of processing things, without being able to be in person, and when you’re protecting people’s privacy. That also means there’s a lot of silence.” This writer called the conflict between Deen and ND “a sad occurrence,” but did not think it represented “a pattern of dismissal or harmful actions.”

Said Deen, “Some people might say, maybe this just happened because of the time we were in. I don’t think that’s true; I think it would have happened anyway. But maybe there would have been more personal conversations that could have happened and might have mitigated something that got lost.”

Of course, it’s hard to argue that this conflict is merely a sign of the times when these structures and systems have been in place for such a long time.

“When institutions are relying on legal advice and litigation, you can track the conversation that folks are having, and you can document the point at which attorneys get involved, because the conversation sounds very different—the tone is even different,” said artEquity’s Morgan. “Often the legal advice they’re getting is from folks who are not necessarily anti-racist, or they don’t have a strong gender analysis. They know the law, but they’re perpetrating and supporting a culture that is implicitly racist, sexist, heterosexist. So it’s understandable why the folks who are experiencing an outsider experience don’t trust that. They’re often not making the situation better; they’re sometimes adding more injury.”

Indeed, whereas Deen said he had not felt discriminated against in regards to the original dispute, the HR review process began to feel discriminatory and harmful. Deen decided to resign from the EDAI Task Force.

“I guess, corporate-wise, every lawyer would advise them to do a discrimination investigation just in case,” Deen said. “I never said I’d been discriminated against because I’m brown and trans, but I think because you look at me and you see that, you make decisions and go down a road that you probably would not have gone down if I was a blond-haired, blue-eyed playwright. You wouldn’t have been worried about a discrimination suit.”

Deen said the situation produced somatic trauma symptoms in him, which affected his sleep and mental health to the point that it negatively impacted his ability to work. “My art really took a hit for the period that everything was going on,” Deen recalled. “I just couldn’t concentrate, I couldn’t focus. It was really hard to work.”

Concurred another resident playwright who knows Deen, “The longer this HR process went on, it caused more and more harm. If this is the process, then the process needs to change, because it clearly caused way more harm than the initial conflict. There still hasn’t been any acknowledgement by New Dramatists leadership of that.”

In Sept. 2021, the HR Task Force announced that it had concluded its review and had found no evidence of institutional discrimination or retaliation. ND was also working with Diaz Inclusion Consulting to conduct a review of the organization’s EDAI practices. According to New Dramatists, the consultants conducted surveys, focus groups, and nearly 40 one-on-one conversations with resident playwrights, board, and staff, including several conversations with Deen and writers who expressed concern on his behalf.

At a community-wide meeting held over Zoom on March 30, 2022, tensions ran high. It seemed that neither the organization nor its members were ready to have the conversation, and many reported contentious exchanges with board members. A facilitator from Diaz Inclusion established ground rules, expectations, and community agreements for the meeting, and allotted time for people to raise issues and respond.

“A lot of people in the community wanted there to be a meeting because people felt like they were in the dark,” said one writer. “If one of our residents was suffering, we wanted to know why, and we wanted to know how to help. It was a rift in the family. We wanted to be able to bear witness and be there to help fix it. However, the format of the meeting, the way that the meeting was facilitated, and the way that certain people felt like they could behave in the meeting, made it so we weren’t able to have the discourse that we could have had.”

Brown confirmed that “there were a number of hard things said by a number of people in that room,” but given the community engagement arrangements made before the meeting, one of which vouched for privacy, she was “not comfortable speaking to any of them.”

As artEquity’s Morgan put it, “If the conditions are not right for people to speak truth, then you’ll just once again be talking past each other. It’s important to go back to those group agreements, create a high feedback loop, be committed to the process, monitor those group dynamics, and just maintain a high level of candor. People with the most positional power need to get a lot of feedback, and they almost need to overly invite the feedback. Then when they get it, they need to believe it.”

“Organizations are trying to get to this better place, and that takes growth,” Deen observed. “Growth is sometimes uncomfortable.”

For his part, Deen spent the next few months in discussions with ND staff and an EDI consultant he enlisted about ways to complete the final two years of his residency. Deen requested to be removed from a majority of the organization’s communications and to conduct his two remaining extended workshops offsite. Deen also resigned from the board of directors, expressing a desire to take a step back from the organization.

“It hurt so much that I needed a break,” Deen said of this time. “This is the most disempowering experience I’ve ever had in the arts.”

The last straw came when, Deen alleges, he was directed to conduct further communication with the HR staff person, and that his consultant could not be included due to privacy issues. All communications about the accommodations he had requested for his remaining workshops, to which ND agreed, would have to be conducted directly, and confidentially, with ND. Deen wrote in his letter that New Dramatists’s communications became “even more legalistic and impersonal,” and that their proposed arrangement amounted to asking him to talk about his playwriting work with an HR intermediary. “That’s just not how it works,” he said.

Since Deen chose to resign from the final two years of his residency, he has found other organizations to host his development workshops. But he said he still feels a heavy loss.

“It’s the loss of a home, the loss of people I respected and cared about,” Deen said. “Some people really came through, so as a silver lining, I discovered some allies I didn’t know I had, and that’s a wonderful thing. But at some point, I had to leave, and it does feel like—well, I guess everyone went on without me. I don’t mean that to be a pity party for Deen. I know I chose to leave, but I really feel like I didn’t have a choice at that point.”

He wants to focus on writing and get back to being creative. But he’s telling his story now because he hopes it can be of benefit to the field.

“Half of writing is taking something that is terrible in the world, and turning it into some alchemy,” said Deen. “So if this public letter leads to you writing about it, which leads to some small shift in the field, where then we don’t resort to these kinds of processes, but to something that’s more humane, then that’s at least something good coming from it. It sounds like a lot of people have this happen to them but sort of quietly go away. So maybe they’ll feel less alone in it, because they’ll realize it’s happening to others.”

As for New Dramatists, their work is still in progress. The EDAI committee (formerly task force) has been working toward more inclusive and equitable practices. With support from Diaz Inclusion, the organization is working toward the ratification of an EDAI mission statement and set of stated core values.

“During the fall,” Morse said, “we created a working group of a combination of board members, playwrights, and staff, who then were led through process assignments and tasks to draft an EDAI mission statement that included statements of value. We just had a board meeting at which it was looked at and ratified. It’s now in the hands of our HR committee to use as a basis to come up with a community agreement, and will be disseminated to the community, the rest of the staff, and the playwrights.”

The Church is back in business too. New Dramatists was recently able to host its first in-person PlayTime series since 2019. The workrooms had been adapted to suit a virtual platform, but the playwrights are now able to continue their work in-person, in the company of other writers. (Due to the accessibility limitations of the Church building and its lack of a central HVAC system, the organization has decided to list the building for sale, and the New Dramatists real estate committee is in the process of making those arrangements.)

Brown and Morse said they didn’t think anything would be gained by responding directly to Deen’s letter, but Brown added, “That’s not to be dismissive. When eventually our core values are posted, you will see that we talk about community, acknowledging that disagreement exists, that feelings are important—I think it’s sacrosanct to allow people to have those. We certainly stand by our actions, stand by our process. At the same time, I do not want to give the impression of arguing with someone about their perspective, which they are totally entitled to have.”

Of the 20-plus resident playwrights I contacted, the majority did not want to be interviewed, and none wanted to be quoted by name on the record. So the question remains whether the field, New Dramatists included, has the capacity for an open conversation. Said one writer, “As a result of this situation and how the organization has handled it so far, there are people who no longer feel as safe at New Dramatists.”

“It’s strange,” they continued, “because the ask for mediation—to just talk about it— feels so straightforward and has been consistent from the moment it started. That was all we wanted, and still want.”

Fortunately, artEquity’s Carmen Morgan sees an opportunity for change on the horizon. “The conditions are really right, right now, because there is a demographic shift. We already know that more and more people who identify as female, more and more people of color, are in the workplace and in positions with positional power. This is the widest continuum of generations that we’ve ever had in the workplace. It’s exciting to have three or four generations in the workplace at the same time. These are some of the issues of difference that we’re contending with. If we get this right, it will transform our culture in ways that we’ve been waiting for.”

There’s ground to be gained, if organizations can put in the work.

“It is my great hope that New Dramatists continues to thrive,” said one resident playwright. “But what I think that means is that there needs to be some coming together as a community, and work done from everybody to keep the community strong or it’s not going to survive.”

Alexandra Pierson (she/her) is associate editor of American Theatre. apierson@tcg.org