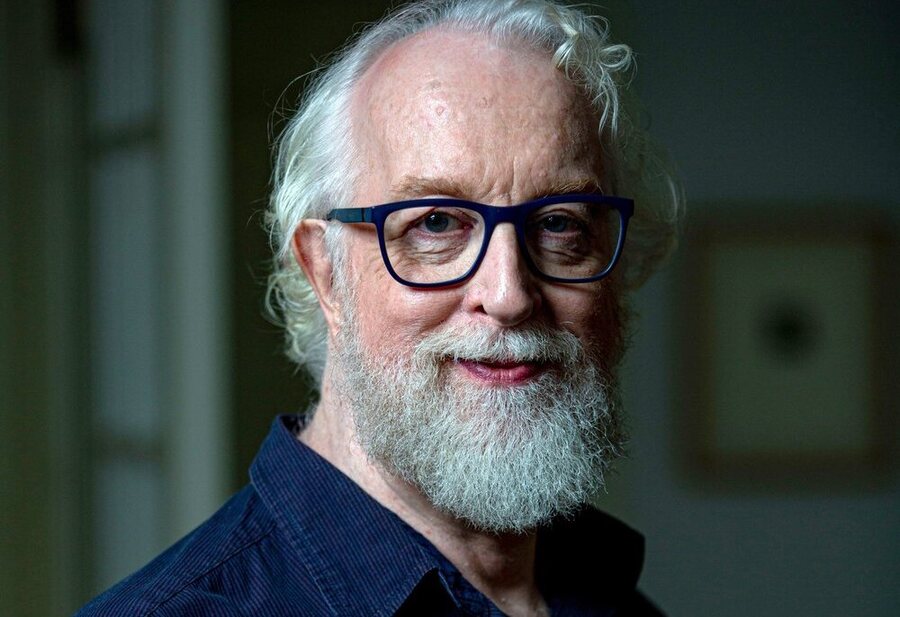

Tall, bearded Robert Falls could almost be a mascot for the City of Broad Shoulders. But the longtime artistic director of Chicago’s flagship theatre, the Goodman, who stepped down from the post last fall after 36 years in the job, doesn’t just loom large physically. He has long had ambitions to match, as he built on the strong national reputation forged by his predecessor, Gregory Mosher, and worked alongside executive director Roche Schulfer to maintain the Goodman’s role as a leader in both new work and classics, minting or reconceiving some American classics along the way. But for all his strong individual artistic vision, Falls did not run the Goodman as an aesthetic autocrat but fostered an Artistic Collective of associates with a stake in the programming (which also, as a side benefit, allowed him to forge a busy career as a director both at the Goodman and outside of Chicago, including repeatedly on Broadway).

Falls, who recently turned 69 and whose successor is Susan Booth, is now directing The Cherry Orchard at the Goodman (April 1-30). While he told me in a recent interview that he hopes this is not his last run around the Goodman track, there is no mistaking the valedictory quality of this choice. The following conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: The Cherry Orchard is a play about losing a home, a way of life ending. As you also recently left the place you called home for so long, does it feel a bit like a farewell statement?

ROBERT FALLS: I think it can’t help but resonate. With anything I do, I bring a deep personal connection to it, although I often find it’s incredibly unconscious. I’ve been very fortunate from the beginning to create a career and a home for myself at the Goodman where I was able to alternate between doing a new play and doing a classic work, and to create that dialogue between the classic and the new. For example, many years ago I was working simultaneously on Three Sisters while at the same time working on Eric Bogosian’s SubUrbia, both of which are about people trapped in a milieu and their circumstances and not able to get out. That wasn’t necessarily conscious, but that’s what happened.

So even before I made the decision to step down after a long time at the Goodman, I knew that I was moving toward The Cherry Orchard. Having directed four other plays by Chekhov: Ivanov in college, when nobody knew that play, Three Sisters in the ’90s, and then a rather life-changing experience doing The Seagull in 2010, followed by Uncle Vanya. And yes, Cherry Orchard—a lot of major directors over the years have used it as their swan song, but for me it was a little accidental. It was only really around the aftermath of my stepping down that I of course realize that it is a play about transition, that it reflects on arrivals and on departure. The fact that it’s a play about change, about a new generation coming up, a sort of new world, and people don’t quite understand what that’s going to mean, either the people who will become the inheritors of the world or the people who are leaving it, who’ve been displaced—it does seem to have some resonance. I think for somebody who has been at the Goodman as long as I have, it is a letting go. Though I think I’m going to be much better off than the Ranevskaya family.

I looked up an interview with you from years ago in which you said that the Goodman’s board was pretty divided about hiring you in 1986, and that you got the job thanks to just one tie-breaking board vote. Why was the board so equivocal about you, and did you win them over?

I mean, I was a pretty cocky and confident young man, making a transition from the Wisdom Bridge Theater, where I had been for 10 years. I went through a fairly rigorous search process for the Goodman job, and was fairly aggressive in talking to the board of directors and trying to lay out what my goal for the theatre was. Gregory Mosher and Roche Schulfer had done a brilliant job in terms of establishing the Goodman as a home for new writing. But as Greg will say himself, he lost interest in the mainstage and his personal focus was more toward the very small 120-seat studio theatre. I personally was exploding with ambition and size. I’d outgrown the Wisdom Bridge, with productions like Hamlet and Mother Courage and Her Children. So I had a vision for the Goodman that was rather grandiose in terms of big Brecht productions, large Shakespeare—I felt that the classic work hadn’t really been investigated. Of course, those productions were all very expensive to do, and I needed to know from the board of directors that they were going to support the vision I was bringing, at a time when the theatre was facing a multimillion-dollar deficit and they were looking at a much more conservative direction. I insisted on interviewing all of them, at the same time that they were interviewing me, and I think that rubbed people the wrong way. I had my detractors as well as my enthusiasts.

But that was the direction I went for a long time, putting new plays alongside older plays. I really did think that the only way this theatre was going to regain its mojo and attract audiences and money was by going big at a time when everybody wanted to go small. I think it was indeed proved that was the right direction for the Goodman at that time.

From the start, you brought on associates and colleagues, including Frank Galati and Michael Maggio, and you still have a group called the Artistic Collective. So though you came in with a big vision, it seems like you knew you couldn’t realize that on your own.

Some of that was quite informed by Todd London’s The Artistic Home, which TCG was very involved in. I was a very early person working with Todd on the support of the artistic associates and of providing an artistic home. You know, running the little Wisdom Bridge Theatre on the North Side was essentially all me all the time; I would pick a season of five or six plays that I liked a great deal, I would direct two or three of them, and then I would figure out who to hire to direct those other plays. I didn’t think that was the best way to run a theatre, and I had been enamored of the work of other theatres around the world, particularly Citizens Theatre—I received a grant to go to Scotland to look at their work. At the time it was led by a playwright, with a collective running the theatre. I was also enamored of the sense of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and a commitment from the Peters and Trevor—Peter Hall, Peter Brook, Trevor Nunn—while I believe that Hall was officially running the theatre, they all had the common goal of the work and were associates. So from the beginning, I didn’t want to experience that loneliness. I wanted to have colleagues around and to bounce ideas off of, and also to take advantage of their best ideas. That became the centerpiece for the Goodman from the mid ’80s, all the way up to this moment.

And, of course, at that time, it began with three white men, and over the years it became far more diverse, actually quite early on. And the fact remains to this day that we need to create artistic homes so that artists have a deep relationship with the community, with the board of trustees, and with the staff of the theatre.

Of course, you don’t have to go all the way to Scotland to find a theatre collective. There was a pretty famous one right there in Chicago. From the start, did you consider Steppenwolf a competitor, even a rival?

No, some of my closest friends to this day are people that I met in the early 1980s, members of the Steppenwolf company—they’re personal friends and colleagues and people who’ve worked at both theatres. My vision was more of a director-driven theatre, but it was never like, “Oh, there’s Steppenwolf over there, an actor’s ensemble.” And that changed a lot when Martha Lavey became artistic director; she brought in more of a director’s perspective.

Chicago theatre is also characterized by a certain frankness, even fractiousness—that’s how it looks from outside, at least. Is that how it feels from inside?

From the beginning that was one of Chicago’s strengths as a theatre town. You know, I was probably a rock thrower, throwing rocks at the Goodman and other people when I was at Wisdom Bridge, and I certainly expected that as I took over the Goodman that there would be rock throwers from a new generation kind of coming up. But it was always in a collegial way.

Does it still feel collegial?

I think so. As you know, Chicago is in a giant transition right now, not just with me, but all over the place, in terms of artistic leadership. And as with Cherry Orchard, that transition is pretty profound. Obviously, there’s a profound change from what was essentially a second generation of artistic directors. I was really influenced by Adrian Hall, whose recent passing was very moving to me, as Adrian was one of the first directors to identify me—mentor might be too strong a word, but I was overwhelmed by his work, and I’m a link to Adrian Hall. And now we’re making big transitions, and Chicago is going through that too. For a long time it felt quite collegial, and it still is—you know, unlike communities that are constantly bringing in actors exclusively from New York, 90 or more percent of the actors and directors here move from theatre to theatre to theatre.

You were at the Goodman for 36 years. At what point did you think it was time to head for the exit? Was it a case of, “I’ve had my say,” or that you felt it was time to hand the reins to someone else?

All of those things. Clearly we don’t quite have the same sense of term limits in this country in terms of artistic directorship as they do in the U.K. And for better or for worse, as I said, creating an artistic home was very much at the center of my thinking. The majority of the Artistic Collective have been there for a long time too, and I think that’s because they were provided with a home. I felt that home was successful for our audiences and for the community—a long-term successful relationship. And I just felt, moving into my late 60s, that I was ready for new and different challenges, and I was willing to say: I think I’ve said a lot here, I’ve been able to have tremendous opportunities. I was beginning to think that 35 might be it—I was pretty confident I wasn’t going to get to 40. And then we hit the pandemic. That was, as you know, not an easy time for any of us in the theatre. And that possibly accelerated a little bit of my thinking that yes, this is the time to turn it over to other people.

In addition to the pandemic, of course, there was the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement and the We See You, White American Theater document. Did you feel personally challenged or called out by that? Did you read it as saying, essentially: Here are some huge blind spots that need to be acknowledged, and some changes that are long overdue?

I would agree with both of those statements, and those are exactly the same things that were directed toward TCG and many other organizations. It was a reckoning that was due. I have felt that the Goodman has been a leader in diversity and equity, and I’m very proud of that and felt very connected to our community and the artists within our community from the beginning of my administration. Which is not to say that there were not moments of difficulty. The Goodman is a lot better theatre for having had the questions asked by We See You, White American Theater, which we took very seriously; each and every thing was discussed at the theatre.

I’m going to ask you the kind of question you probably hate, but here goes: What are you most proud of in your tenure of the Goodman?

I have to say, honestly, that the ability to support the Artistic Collective, and the diversity of that group and its relationship to the community of a very complicated city, as Chicago is, has been my greatest satisfaction. To create this collective and to collaborate with all of them, and to create a theatre for everybody, for all Chicagoans. Roche and Gregory Mosher were committed to that in the mid-1970s, so I’m the inheritor of an aesthetic that was already being laid out. I’m very proud of maintaining excellence and at the same time pushing the theatre when it needed to be pushed. I could go on and on about not just individual productions but groups of productions—the Goodman had a very early long relationship with August Wilson, and was the first theatre to do all 10 of his plays a long time ago. And similarly, to be able to devote myself to the works of O’Neill and Miller, and the number of festivals the theatre did devoted to single writers, was very important.

What do you think has changed the most about the theatre field in the time you’ve been at the job?

These are the questions that I dread the most. I neither have a crystal ball for the future nor a perspective on history—I wish I did, but it’s hard, because I sort of feel in the middle of it and that it’s constantly moving. It’s like looking at the ocean, and you kind of go: All of that water is new, none of that water was here 30 seconds ago, or 30 years ago, or 300 years ago. All you feel with your feet in the sand is that it’s coming in and it’s going out.

I was just talking to my wife about how we were in a culture war at a certain period of time—the Mapplethorpe incidents and Karen Finley. I was there at Congress, working alongside Peter Zeisler and others with the National Endowment of the Arts. And now we’re moving into a whole other set of culture wars right now—it’s insane. Trying to ban drag performances? The more things change…

But I remain optimistic that the theatre has been around for a long time, and it’s going to continue. I just feel that way. There’s no doubt that our younger audiences brains’ have been rewired by the speed of the culture. But honestly, I sit with young audiences looking at an O’Neill play or sitting watching an August Wilson play or a Stephen Sondheim musical, and I see people whose lives are changed. I don’t think that is going to go away.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org