The following essay comes from authors Mallory Catlett and Aaron Landsman, whose book The City We Make Together, was published by the University of Iowa Press in 2022.

In a democracy, we take a certain kind of representation for granted: People in elected office are supposed to speak and act on behalf of their constituents. They represent us, and often try to show their qualifications for doing so by empathizing with our concerns and struggles. When we talk about representation in a play, we often ask another question: Is the person onstage appropriate to play this specific character? Both of these representational “acts” hinge on belief and trust.

We started making the participatory performance City Council Meeting in 2010, to get the audience to reflect on why they do or don’t participate in civic life. We tried to stage a conversation about participation: why we make the choices we do, how we perform power, and who gets to play which roles. Following Plato’s advice on democracy, we assumed viewers had all the qualifications they needed to lead or be led; we didn’t have to teach them anything. Instead we structured the performance by asking for real communication among its participants, through a set of instructions and rules, and not the representation of communication, as occurs in traditionally scripted dialogue.

After our last performance in fall 2014, we felt there was still energy left in the project. At least two people had run for office after working with us on it, and there were still offers, if not resources, to present it again. So we started teaching and writing, which led to our book The City We Make Together, published by the University of Iowa Press in 2022. This has led us to a new set of questions about the way we value representation in politics and theatre, and a new way to think about teaching civics through performance.

One of the key tensions in our show was that it put the choice in each viewer’s hand about how to perform difference. Viewers decided what kind of role to take on—from bystander, to speaker, to supporter, to councilor—but we didn’t tell them who specifically they would read for or how to perform. The assignment of texts within the piece was random, which meant you might have to say the words of someone very different from you.

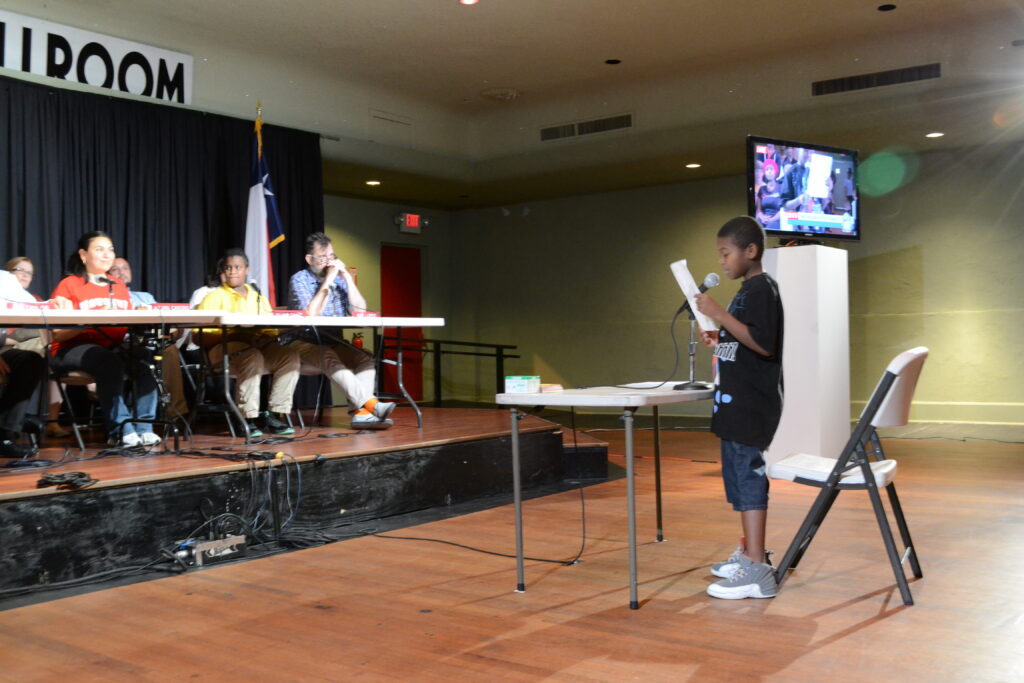

We didn’t want audience members to feel like they had to have a set of special skills in acting to get it right. We tried to make it clear in a myriad of ways that the job was simply to voice what they found on the page in front of them as clearly as they could—to render the words of a real person, likely a stranger, for the viewers gathered in the room. We reminded each audience that the words they were saying had been spoken by someone at an actual city council meeting. Watching diverse groups of participants address this gap in identity—what philosopher Jacques Ranciere calls the “irreducible distance” among people in an audience or a citizenry—was, for us, the point of the piece.

Here’s how we described this dynamic of representation in the book:

When a 30-year-old bearded white man from Williamsburg [Brooklyn], who carries all the outward signs of a “hipster gentrifier,” has to say the words of a 17-year-old African American woman from the East Side of San Antonio, who is testifying about disinvestment in her neighborhood, it’s a tricky line to walk. For the self-aware, representing this perspective and taking responsibility for these words creates a beautiful tension.

Ideally our performance tried to reflect questions, rather than solve them: How does this audience member think about representing others? What kind of care do they take with a stranger’s words and beliefs? How much respect do they have for those who are not like them and they don’t know?

Since we started writing The City We Make Together in 2015, we have been through a lot, politically and in the theatre. We’ve seen the election of 2016, the COVID pandemic and the resultant onset of digital government meetings and digital performance, and then there was the Jan. 6 insurrection. We’ve supported ongoing uprisings across the country for the sanctity of Black lives, both in the street as well as in our field, through organizing like We See You White American Theater. City councils are changing too, often toward the kinds of performative acrimony and factionalism that have emerged nationally. What could that mean for how our work as artists might be perceived?

We have found that reactions to the book, specifically from readers who had not experienced the show in person, sometimes include a thoughtful challenge. Could an audience ever get accurate or fair representation right? Could a trio of white artists (including our third collaborator, Jim Findlay) bring a diverse audience together in a really equitable way? These readers were sometimes skeptical that our above-mentioned hipster audience member could, or should, read aloud the words of a Black female-identifying teen. Surely these doubts or questions are grounded in countless examples of the poor handling of difference by artists working without sensitivity, even if their intentions are good.

These provocations by readers of The City We Make Together bring up a new way to frame our own inquiries. Instead of thinking about how we applied theatrical tools to a city council meeting, we are thinking about how we applied city council rules to theatre and acting, and what the switch could mean in both arenas, as well as in the classroom.

From the book:

Ideally our piece exposed the performativity and limitations of a government meeting and exposed viewers’ presuppositions within it. Could it also give us opportunities to see those limitations as openings through which we could alter the political fabric of our cities? Could enacting a government meeting as art allow us more freedom to change the structure of actual governmental processes? As several cities in recent years, from Portland, Me., to Oakland and New York City, have begun integrating artists and creative processes directly into local governmental structures, the answer seems to be yes.

The limits of identity-based representation in politics have revealed themselves graphically in the last year. Long Island Republican Congressman George Santos constructed an elaborate persona, a character based on lies, in order to make himself sympathetic to voters. He claimed to be “Jew-ish,” complete with a Holocaust-surviving grandmother; he claimed to be a varsity athlete at a college he never attended; he claimed to be a successful businessman, a friend to victims of gun violence at the Pulse nightclub, and an LGBTQ ally. We’re sure this list is incomplete. It seems his goal was to make himself more sympathetic, believable even, as he courted voters.

We often see U.S. mainstream theatre rely on a set of principles in casting, which in its way can sometimes be similarly problematic. We cast people based on perceived identification and sympathies. Do the limitations of how we traditionally engage casting and portrayal foreclose possibilities for the field’s transformation? Is there a better way we can actually inhabit all the thorny histories in each of our bodies when we commune with audiences?

What we have found in creating this emergent body of performance, publication, and pedagogy is that, at the very least, we are hungry for an approach that takes into consideration what Brecht and Boal have to say about representation, and move forward from there. This is also a reason to better understand, teach, and utilize non-Western traditions that might take us past some of the limits of representation in American politics and theatre.

As always, artists and critics of color are offering possibilities for us to build different ways of seeing in the theatre. Aleshea Harris’s What To Send Up When It Goes Down asked us to be in the room differently based on our identities; Daniel Alexander Jones’s practice often embodies an honest communion among people of different backgrounds while honoring the spaces between us and the often difficult truths of our differences. Writer-performer Heathcliff Saunders acknowledges progress on Broadway in increasing the numbers of Black performers on its stages in his 2020 article “What I Think About When I Hear That Broadway Is Racist,” but adds, “The story of race in American musical theatre is we will overcome racism by not seeing Blackness… Black bodies are not Black lives, and Black lives are not Black bodies. More bodies alone will not change the story of Blackness we’ve been telling.”

And of course there are groups that have been making new ways for communities to perform beyond representation for a long time, from Cornerstone to Los Angeles Poverty Department to Theatre of the Oppressed groups everywhere. Our hope is that our work joins theirs in continuing to broaden the field.

Perhaps another thing that joins these two discussions of representation, from theatre to civics, has to do with institutions themselves. If it’s still mostly white people running theatre, presenting spaces, playwriting programs, and funding sources, will better demographic representation, or cautions about it, ever build actual liberation for the field? In government, maybe we need to go beyond simply electing people who make us feel comfortable in the way they position themselves as “representing” us. If we are constantly trying to build more equitable representation, but it’s always within a system built on white supremacy, how far can we take that?

As we begin to work with visionary theatre artist and educator Ebony Noelle Golden to build a curriculum based on City Council Meeting that can scale out to schools across the country, we continue to be interested in how to stay focused on systemic transformation. Can kids learn organizing tools that both shed light on the systemic shortcomings, while also learning how to be better engaged in the systems as they are now? Can the tools of live performance help? We are hoping to go beyond simply “giving voice”—by itself another form of representation that doesn’t always produce results—toward new civic structures and potential systemic change.

We are thinking about how the rules and framing of our original questions change from the theatre to the book to the classroom. Audiences and readers are more likely to come to a show by choice, while students are assigned materials whether they want to engage with it or not.

So when we run workshops, we often add some prompts that allow a diverse classroom to feel more protected. We tell students they can refuse to engage with material that puts them in the position of speaking for someone demographically different from them; they are welcomed to name the discomfort they might feel, or to turn over a piece of text to someone else; they can call bullshit on our whole endeavor, which is another possible way to take part in a democracy. While we have had partners at universities who worry about student fragility, we find that when we open up these new options, students have been eager to dive in. It creates an opportunity to talk about how this question of representation factors into one’s choice to participate fully and creatively in civic life. Unburdened by the usual expectations of casting, what roles can any of us begin to play?

Mallory Catlett is co-artistic director of Mabou Mines, an associate artist at CultureHub, and artistic director of Restless Productions NYC. She lives in New York City. Aaron Landsman is a multidisciplinary performance maker based in New York City. He teaches part-time at Princeton and is an artist-in-residence at Abrons Arts Center.