There’s a priceless moment in the sensational new Off-Broadway production of Eric Bogosian’s Drinking in America in which Andre Royo, playing a scuzzy, profane Hollywood agent in the Hurlyburly mold, pauses his phone call to extend the antenna on his phone handset. It not only speaks to the attention to detail of director Mark Armstrong’s finely modulated production; it also firmly places us in the decade of the show’s creation. This is not the cuddly 1980s of John Hughes or The Goldbergs but the coke-fueled Reagan era of greed-is-good selfishness, macho conservatism, and, in turn, works like Bogosian’s, which reflected the pathologies of the age in a kind of gonzo funhouse mirror.

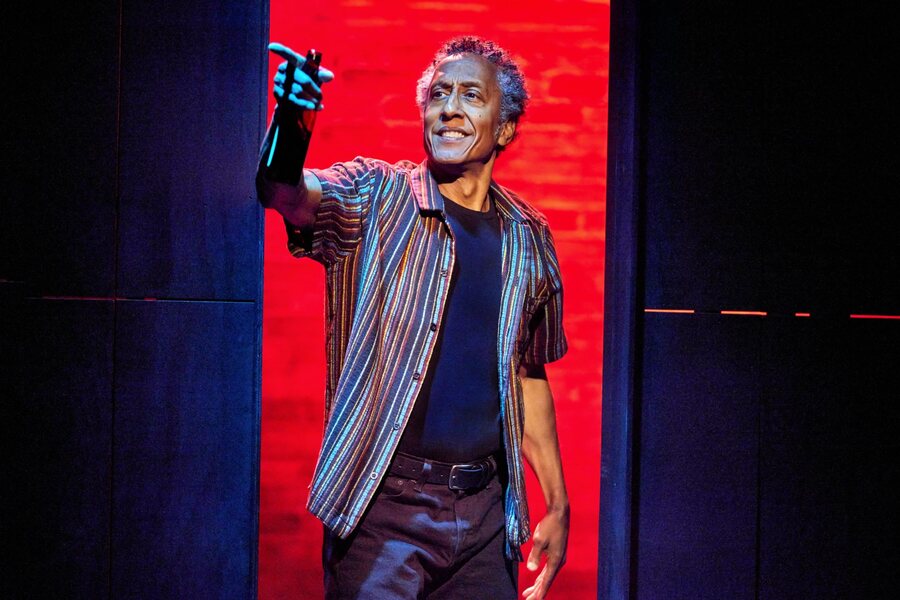

The Bronx-born-and-raised Royo, best known for his indelible performance as the pathetic but noble junkie Reginald “Bubbles” Cousins on The Wire, got his start onstage not long after Bogosian’s heyday, but hasn’t worked in the theatre since 2007’s The View From 151st Street, a LAByrinth theatre production at the Public Theater, in which he also played a needy junkie. For better or worse, addiction is a theme that Royo has returned to and plumbed to great effect throughout his career. But as I learned in seeing Drinking in America (playing through April 14 at the Minetta Lane Theatre, in a production by Audible Theater) and in talking to Royo early today over Zoom, addiction is hardly the only lens through which to read this bravura series of monologues. Indeed, there are many layers of depth folded into its well-earned despair; as one abject junkie character puts it, with the quiet peace of terrible self-knowledge: “Life is the monkey on my back.”

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I very much enjoyed you in Drinking in America, but I also want to take this opportunity to thank you for the beautiful tribute you wrote for us when Craig “muMs” Grant died a few years ago.

ANDRE ROYO: I really, really appreciate that, and I appreciate Stephen Guirgis for recommending me to write that. I was so fearful, so scared and emotional, but when I finally did it, it really did soothe my soul. So I appreciate having the opportunity to speak on my friend. I miss him terribly. And he’s here with me onstage—he always gives me notes at the end of the show. It’s an honor to him. You know, he was one of the reasons that got me to get sober and reclaim my joy of acting, and reclaim my position onstage. Because that’s something that me and him growing up in the Bronx always talked about. When I first started acting, I saw myself being some Broadway guy, coming out the side door to sign some Playbills and then hitting the bar. That was the dream of the actor until I heard, “I’m pregnant.” That dream went away, and then it was Law and Order.

You just answered some of the questions I have for you. But say more about what brought you back to the stage after 15 years.

You know, like for all of us, COVID was the scariest thing I saw. The pride of being a New Yorker is that New York is the city that never sleeps, it’s the hustle and bustle of the rat race, if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere. Even when 9/11 happened, we had a pause, and then we started selling T-shirts. But to see Broadway close, to see the city empty—that scared me, and really hit home. And you know, I think I was in Tahoe, and Trader Joe’s was selling Suntory whiskey at $30 a bottle, so I was stocking up and just drinking, drinking, drinking.

Then muMs passed away, and I just felt felt—I didn’t think acting was gonna matter to me anymore, and I noticed that with film and television, it felt weird. There’s 500 channels, and everything was so fast: cut, check, print, move on. I wasn’t in love, or I didn’t feel the passion as much as I used to. The only thing I knew that would bring that back is where I started, in theatre. So when the opportunity came to get back onstage, I went for it. It was a challenge, and there were obstacles. You tell your agent and manager you want to go do theatre, they think, “Okay, he’s drunk—let’s book him a job, we’ve got to get him out of there.” I had to really put my foot down and tell everybody: “This isn’t what I want to do, this is what I need to do.” And it helped me with my sobriety, it helped me with my creativity. It saved my life, so to speak. Because there’s nothing like the stage. I got the ball rolling, and here I am. It’s a moment in my life that I’ll never forget.

Me neither. I wonder, though, in coming back to the stage, were you really bargaining for such a strenuous solo show?

Well, a part of that is, I’m a Bronx-born-and-raised New Yorker, and my ego is really, really big, and if I’m going to really go onstage… [Laughs] There were other projects I wanted, I’ll be honest. The first thing I wanted to do was Talk Radio. That’s what got me on the phone. I knew Eric Bogosian through my buddy muMs; we played poker together at Eric’s house. And Talk Radio was always circling around. But then with Audible and Talk Radio, some red tape got stuck, and Eric was like, “How about Drinking in America?” And I read that, and I was like, “Oh, no—it’s a one-man show. It’s been 15 years since I’ve been onstage…” And Eric gave me that little look, like, “Well, when I did it…” And I was like, “Okay, wait a minute, my man—if you could do it!”

I was scared; it was a heavy lift. But when I read it a couple of times, it would calm me down; I just saw myself in all the characters, in my journey of being an artist, and drinking; I’ve been all these guys at one point or another in my mind. That made it a little easier for me to comprehend doing it. Then the rest was the rest was the work ethic, you know, just grinding. And Audible put a team around me that was just fantastic, that really created a space for me to nurture my creativity and become fearless in my choices.

It strikes me that the show is more about America than about drinking, though there’s a thread of some kind of addiction—in the case of the Cuban diner owner, for instance, he doesn’t drink or use drugs, but he’s a sort of workaholic. Am I on the right track?

Yeah. When I did when I did The Wire, that was my first introduction to drug addiction, in creating Bubbles. With no judgment of any of these characters, including Bubs, I had to understand that we’re all addicted to something: sugar, watching TV, capitalism. So you understand it’s the drive, the push, the hunger to achieve the American Dream, which is really based on capitalism. They sold us on the idea that if you work, you will get the success and the dream and all the things you want. If you can’t handle it, you will buckle—but then go have a cocktail. Liquor is so ingrained in our system; it’s something that we use to celebrate, it’s something that we use to medicate. It’s not a bad thing—until it becomes a bad thing. So when I looked at all these characters, like [my director] Mark [Armstrong] said: It’s really not about any one substance, it’s about your addiction to achieving.

And it’s all these men. Growing up when I was young, looking at my dad, all the men in my life, they constructed a box where they said: We have to protect, we have to provide, we can’t be soft, we can’t be weak. We can’t ask for help. Good guys finish last. If you’re too smart, you’re a nerd, you’re a geek. So we built this, like a ship in a bottle—we built these prisons where we had to be a certain way to be defined as masculine. All those things helped me understand these characters and dive into them in a way of just being human, and not the addiction.

You and are I roughly the same age, and I really appreciated how this play and this production revisit the 1980s. This play’s lens on the Reagan era is pretty dark and cynical: references to subway vigilante Bernhard Goetz, the sermon by the right-wing evangelist. What did it bring up for you, revisiting some of the touchpoints of that time?

It brings up everything, but I was young then, so it hit me different. I was in the era when hip-hop started. We did that; we had a voice. Bernie Goetz and all that stuff, that was grown-up shit. For me, it brings back a lot of memories of feeling forever young, fearless, ruthless, hanging out and thinking that nothing was ever gonna happen to me. I love the ’80s. I don’t want to pooh pooh all the bad things that happened, but it wasn’t affecting me in a negative way. It was making me feel real cool. Me and my friends were just talking about how when you traveled in those days, people would be like, “You’re from New York? You’re from America?” We were looked at like superheroes. That’s no more.

Another thing the show feels like a throwback to is that era of solo shows, performance art, even hip-hop theatre. I know Eric wasn’t strictly in that genre, but there were some overlaps and similarities. Was that something you were tuned into then? Or were you more into straight-up hip-hop?

A little bit of both. In the ’80s, we weren’t coming downtown; we stayed in the Bronx. All we knew of Manhattan was that’s where people went to work. It wasn’t part of our culture. But one of my friends went there and came back like, “It’s crazy down there!” Nell’s, The World, The MK. When I started coming down with muMs, we were hearing about Miguel Piñero and the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. That was our little world. And then John Leguizamo—he was the big dog. He was the big deal before Danny Hoch. So we were getting educated in those type of voices.

And I remember late night, watching—back then it was called WHT, in the Bronx that was our cable—and I saw Talk Radio, and I didn’t know why I was enjoying it. It was just magnificent, and that diatribe that he was talking reminded me of Morton Downey Jr. I liked his energy. I’ve been told I have the same kind of energy in my neighborhood—I can go on and on, as you can tell right now. When I started going to HB Studios acting class, it was all about the monologues, about Mamet, people that had fast talk, that grungy talk, talking about the inner city in a certain way.

Like Teach from American Buffalo, hustler characters.

Right. I’m doing Short Eyes and hanging out with Luis Guzmán. That extra edge just spoke to me, you know. Al Pacino, I used to see him in Central Park when I was going to HB studios, and I would look at Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie and Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon and be like: I want to have those rants!

Your performance is very different from Eric’s, but at some moments in the show you actually look a little like him. Did he give you any notes?

We’ve got the hair, we’ve got the long face—Eric is my twin! We should do something together on screen or onstage. But Eric is an artist, and he’s a fan of my work, so he didn’t really impede on anything. He just came in, and said, “Put your foot on the gas, don’t let go. Don’t talk to people after the show, drink a lot of tea. Don’t lose your voice, and just trust—trust that you know that you have this.” He did give two great notes. The first was: By the time I get to the last monologue, where I’m talking to one guy in the audience, there’s a part of me that’s like, “I’m done”—I want to get through it. And Eric was like, “When you hold out your hand for change, you’ve got to stay there a lot longer.” And the second one was funny, he said: “You’ve got to come out for a second bow!” And I was like, “Come on, these people have seen me for 80 minutes, I don’t want to be back out there.” He was like, “No, you’re cutting off the the exchange. You have to come back out.” Other than that, he really left it up to me and Mark to give our rendition of his joint.

Another thing about Eric and Drinking in America. When I started to feel a little nervousness about it, and my managers and agents were hitting me with this movie, that movie—I had to turn that shit down—I was talking to Eric. And he said he wrote this play when he was a year and six months sober, and at the time I was reading it, I was a year and five months, and when I would start rehearsing it would be a year and six months. It just felt like the universe was telling me: “Yo, movies come and go. It’s time to go back onstage, find your joy.” The great thing about being an artist is that you get to use all your pain and all your situations and put it into your art. I talked to my lady and was like, “I’m gonna go to New York and say thank you to liquor for all the good times, and fuck you to liquor for all the bad times.” This is my swan song for now to say, “Hey, liquor. You’ve been well, but I want you in my craft, not in my liver.” Right now, the only thing I’m addicted to is applause.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org