Dancin’ was my ticket out of Boston’s combat zone.

For nearly two years in the late 1970s, I worked as a projectionist at the Pilgrim Theater, a once grand but now decaying palace with a giant marquee that blared “Adult XXX open all nite!” I took the job in stride; all newly licensed motion picture operators had to pay their dues in the neon-and-porn -drenched “zone.” It was that competitive then. As a college student who loved film and was loath to wait tables, working as a projectionist seemed ideal. The union wages were well above minimum and, more important, I had a booth of my own. I read my assigned books and wrote film reviews for the campus weekly on my portable Royal typewriter alone and unbothered. High up in the projection booth, I had neither boss nor public to serve. As long as Angelique in Black Leather and Honeypot stayed in focus and in frame.

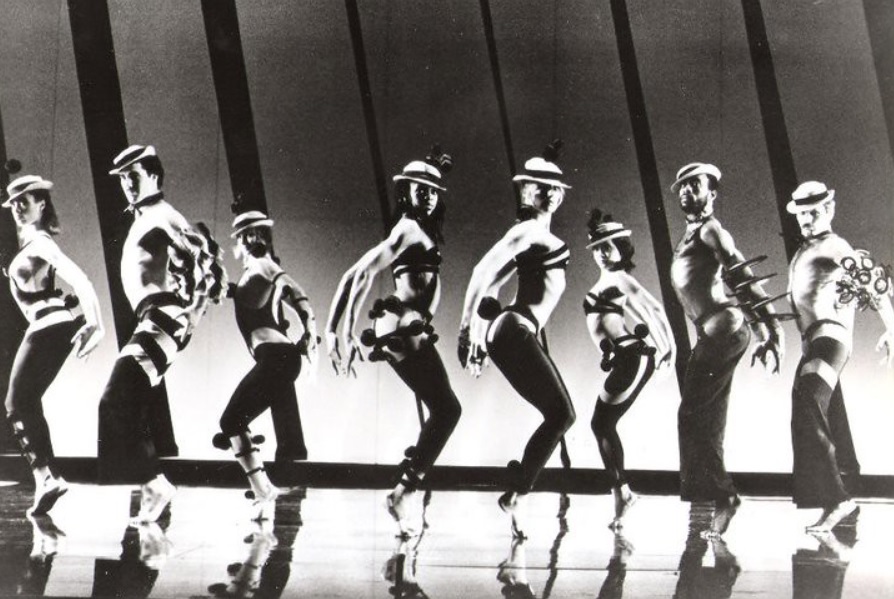

But after two years, the Pilgrim’s outsider/underbelly intrigue had faded. I was eager to move on to a first-run cinema that smelled of popcorn and carpet cleaner instead of mildew and urine. The Local 182 business agent, Mike Canney, offered me Bob Fosse’s musical revue Dancin’, which was headed to the Shubert Theatre as part of a national tour. What would be my part in a live stage show? Dancin’ called for film clips to be projected during two numbers as part of every performance, eight shows a week, Nov. 21 to Dec. 15, 1979.

“It’s just a three-week engagement,” Mike cautioned. “Once the show closes, you’re back on the waiting list.” I didn’t care if the engagement was three days. Just like that, I’d vaulted from the lowly red light district to the shiny jewel box of the Shubert, two blocks but worlds away.

At the early morning call, I entered the Shubert stage door and followed the distant echo of voices down a narrow hallway. My suede cowboy boots clicked like a metronome as I walked across the barren, dimly lit stage. All around me, stagehands snaked thick cables up the aisles and unloaded scenery and crates of costumes from the freight trucks backed up in the alley outside. As instructed, I searched for Fred, head of the stagehands’ union. I spotted a lanky guy with a shock of white hair wearing jeans and a plaid flannel shirt. He was surveying the scene with an air of authority, so I figured he must be Fred. I introduced myself.

“So you’re the projectionist,” he said with a slight smile. I knew he’d been expecting a portly middle-aged guy. “You have the easiest job in the show. But,” he paused and fixed his blue eyes on me, “you gotta get up there.”

He pointed skyward, and I craned my neck to the ornate Shubert ceiling. He meant only the mezzanine, where a Bell and Howell would be stationed on the narrow shelf under the marble railing that ran the length of the first row. My projector would be nestled among the bulky lights and thick black coiled cables. During the show I would operate the projector remotely from the spotlight booth high up in the balcony, but at intermission I would have to climb over the railing and onto the rigging to change the reels of Super 8 film.

That became a favorite moment for me: I got to leave my position in the spotlight booth and hurry down the flight of stairs to the mezzanine, entering from the back and trotting down the aisle, and hoisting myself over the marble railing in front of the first row. Patrons were filing into their seats or leafing through their playbills. There would be a gasp or a stunned laugh, or someone would inevitably say, “Oh, I thought you were jumping into the orchestra!” I’d smile, just getting my job done, a member of the crew. I squatted next to the projector and looked down into the orchestra at the audience murmuring with excitement, shimmying into rows, as I threaded the reel for the second clip, which would play during the curtain call.

I watched the show from the booth in the balcony, on a stool between Moose and Gary, affable guys and seasoned stagehands who operated the whirring, clanking spotlights. Here was yet another booth, with black walls on which various stagehands had printed in white lettering, like Egyptian hieroglyphics on a cave wall or a tomb, the titles of shows and dates of their runs. The black box was like stepping into a rarefied club with its own traditions and rituals.

I heard my first cue through my headset. I hit the start button as “Recollections of an Old Dancer”—which quickly became my favorite among many memorable numbers in the show—began. A silent, haunting, black-and-white moving image of the real Bill “Bojangles” Robinson unspooled against a black backdrop. Performer Frank Mastrocolo appeared at the edge of the stage with a guitar and began his song: “I knew a man, Bojangles, and he’d dance for you.” Bick Goss, with silver hair and baggy shirt, swayed as the aged dancer: “‘Cause I drinks a bit.” Behind him, in the shadows, Hinton Battle was his youthful spirit, a graceful ghost who jumped so high, then lightly touched down. The live dancers mirrored the film in a blur of music, movement, and memory.

Hinton Battle never missed a performance. But Bick Goss’s understudy, Keith Keen, performed Mr. Bojangles a few times, a muscular, agile young man inhabiting the broken body of an old one. Keith was 22, the same age as me, and gay like me—only he was flamboyantly out, and I liked him for it even though I didn’t know him. My role in the show never intersected with the dancers. I kept to myself in my work life as the sole girl projectionist in Local 182. Here among the stagehands, I wanted to enjoy this already fleeting experience without the risk of discomfort that a declaration of queerness might trigger.

I fit in without fully fitting in. I joined Moose and Gary for post-show drinks a few times at the divey Bradford Lounge on the ground floor of the Bradford Hotel, next door to the Shubert, where the crew was staying. Gary was usually accompanied by one of the chorus girls, but not tonight. I took stage sips from one of the Budweiser bottles snaked in a chorus line across the bar; I had an early class in the morning, after all. Overhead a television flashed silently with Ted Koppel’s late-night news of the hostage crisis in Iran. Moose and Gary were loudly kidding with one another about a gift for Keith Keen, whose birthday was coming up. The crew would be at Dancin’s next stop in Philadelphia by then, with another projectionist in my place.

“He does a killer Carol Channing,” said burly, bearded Moose, swiveling on his barstool toward me and taking a swig from his bottle. “We got him a blonde wig. Now we need a picture of Carol Channing.”

“A Hello, Dolly! poster,” said Gary with a shake of his shaggy dark hair.

“I have a Lorelei window card,” I said, pleased I had a piece of prized theatre memorabilia to offer. I collected theatre and film posters for years; I wanted Lorelei, irresistible for the colorful caricature of Carol Channing with a wide, bright red mouth and dangling earrings, because I loved Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Moose and Gary let go a laugh in unison before I’d even finished speaking.

“Lorelei! Even better!” they were saying, their glee spilling over one another’s words. The lesser Channing show was clearly a more inspired choice. I brought my poster to work the next day and gave it to Moose before showtime. Keith would open his gift long after my stint as a stagehand was done, but I didn’t care. Part of me would still be connected to Dancin’.

Dancin’ was doing well but it wasn’t selling out, maybe because Annie was around the corner at the Colonial, or because it was smack in the middle of the holiday season. But as there were always empty seats in the rear rows, I was free to bring guests to the performances—several friends who were theatre buffs, my colleagues at the newspaper, my ex and her new girlfriend. None of them would ever have set foot in the Pilgrim. But here they were, dressed up, playbills in hand, as I led them across the crowded, buzzing lobby to an orchestra seat in the intimate Shubert before I had to dash as places were called.

For Mom and Dad, I bought house seats for a Saturday matinee. They were driving to Boston from Southeastern Massachusetts, just over an hour away. First row, I told the house manager. She looked at me quizzically. Didn’t I want the fifth or sixth row in the center of the orchestra? No, I wanted them as close to the stage as I could get. Dancin’ was my show; I wanted them to have a truly special experience.

I climbed over the mezzanine railing and crouched next to my projector, looking down onto the sea of heads in the orchestra below. There they were, in their seats just a few feet from the stage, staring ahead, waiting. I remembered all those summer stock productions of Gypsy and Mame that we saw on spontaneous day trips to the Cape Playhouse or the Hyannis Melody Tent.

Mom turned and looked up into the lights, just as I instructed, her eyes searching then falling on me, raising her hand and fluttering her fingers. She nudged Dad and he turned, too, with a grin. I smiled down from my perch, as if to say, Can you believe we’re here, practically on Broadway? I gave them a discreet wave just before the house lights dimmed.

I never did return to the porn theatre. It took me awhile to find my footing; I grieved my mother’s death for years. But by 1991 I’d moved to Provincetown to work as a newspaper reporter and was soon covering film and theatre, along with zoning, licensing, and board of selectmen meetings. My first date with Irene was a play, Giggle and Scream, at the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater on June 29, the date we’d forever mark as our anniversary. I felt like my life was just beginning.

Dancin’ burst back into memory when I read in Entertainment Weekly in 1990 that Keith Keen, he of the killer Carol Channing and my favorite Bojangles, was among the many performers lost to AIDS. He’d been dancing on Broadway in Fiddler on the Roof when his life was interrupted at 34.

Film may stop time but theatre lives on only in memory. When Dancin’ returns to Broadway for the first time in 40 years (it opens next Monday night at the Music Box Theatre), what will be revived for me is the Boston run—memories of Mom and Dad turning in their seats to look up at me as I squat next to my projector, the three of us cupped in the Shubert’s palm. “Recollections of Old Dancer” may no longer use film or a projectionist/operator this time, but I will still see that grainy black-and-white moving image of Bill Robinson doing the old soft shoe, mirrored by Hinton Battle and Bick Goss and Keith Keen, strutting and swaying in memory. Graceful ghosts still dancing, forever dancing.

Loren King (she/her) is a freelance entertainment journalist, film critic, and columnist in Boston. Her writing has appeared in The Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and the late great Boston Phoenix.