In 1987 I was hired by the Rolling Thunder Theatre Company in Brantford, Ontario, for a 10-week contract. I would brainstorm with the cast, write and direct a new play, then wave bon voyage as the Thunder van ambled off for 10 months of touring.

Rolling Thunder was unique. Four of the five actors had disabilities, three with cerebral palsy, or CP. The fourth actor was blind. “Legally blind,” he said with a smile when we were introduced. “I’m not breaking any laws.” The cast members certainly weren’t seasoned performers, but each one brought the life experiences Rolling Thunder needed. The world through their eyes—that pretty much summed up what the company was all about. (A token able-bodied actor rounded out the cast since there’s always some heavy lifting to be done on the road. As for myself, I was part of the non-disabled world—at that time, anyway.)

The brainstorming began. Instead of needing to prod or encourage the cast to speak up, I had to slow things down, dig and draw out more of their own feelings and opinions. Details, details, details. How did they navigate through, and cope with, a world that often seems built only for shiny, healthy bodies? The able-bodied world, I kept hearing, could try to imagine living with a disability, but they (myself included) didn’t know what it was really like.

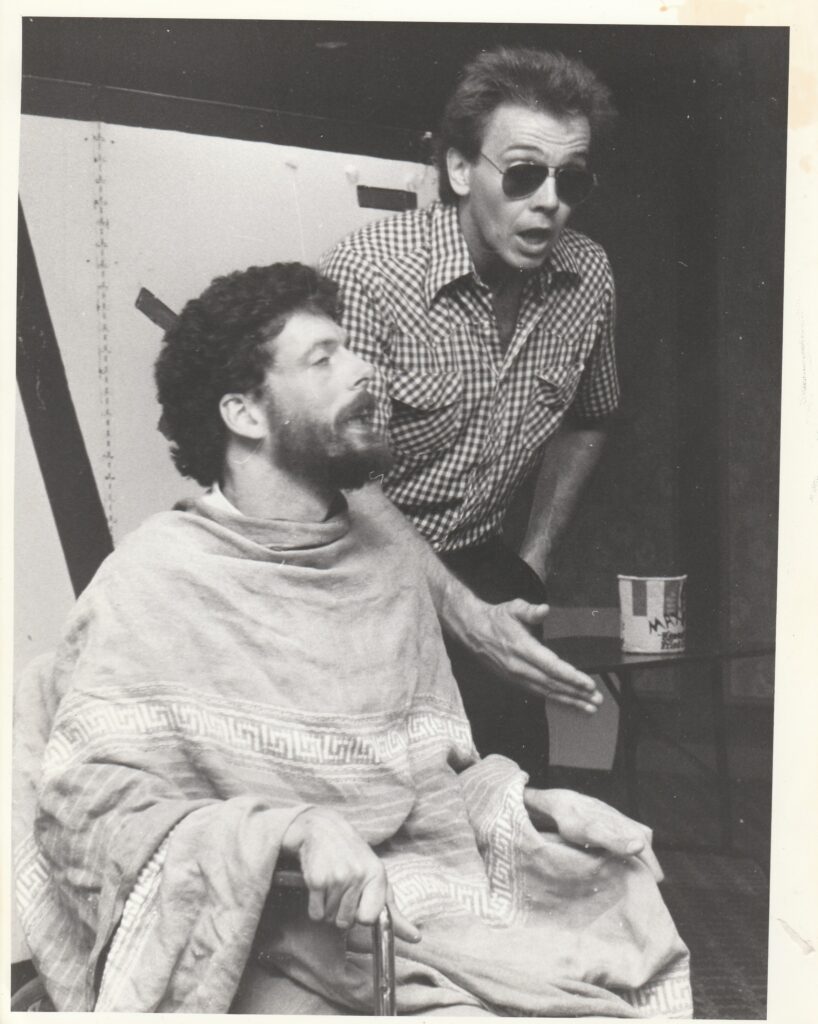

A scene from “A Good Hard Look” with Jim Crawford, Mark Wilson, and Al Sunisloe, who has CP, and uses an alphabet board to communicate.

The “poster boy” for Rolling Thunder, I still believe today, was Jim Crawford. Or, as we nicknamed him, “King.” Jim had cerebral palsy, but with gutter crutches cradling and supporting his upper arms, he could walk. His speech was somewhat impaired, but it did not take very long to get used to the rhythm and timbre of his voice and understand what he was saying.

Jim was gifted with comic timing. He was our king of comedy. He could play a scene broadly, his long face erecting an exaggerated “Who, me?” innocence, or go small with a single word or raised eyebrow, at precisely the right moment, drawing big laughs from the surprised audience. He wasn’t fulfilling a quota in a make-work position; he was in Rolling Thunder because for the first time in his working life he was the right person for the position. The best choice.

“The quieter the audience becomes,” Jim said when discussing skits with a hard edge, “the more I like it.”

He also admitted that he couldn’t stop hating his disability. But while cerebral palsy and seizures and a congenital heart condition (how’s that for a trifecta?) took more of a toll on him with each passing year, he refused to let the disability dictate his life completely. He wasn’t about to, for example, stop relaxing with something to smoke or drink, or give up those hot chicken wings from Flings Take-Out while watching, yet once more, Scarface, his favorite movie. Time, he believed, had never been on his side. Broccoli or spinach wasn’t about to swing things the other way.

❦

The brainstorming gradually evolved into The Off Ramp, a series of skits.

Rehearsal went slowly. One challenge was helping manage the energy levels of the actors. Able-bodied actors can cross the stage, be stopped, do it another way, then another, as they grow into the role. But the cast in Rolling Thunder, while needing to go through the scenes repeatedly, did not have enough juice to do it for very long before their energy and concentration began to flag. Progress came in bits and pieces, and on several occasions what I saw in rehearsal seemed like anything but progress. The dedicated cast persisted, however, and eventually built believable characters, a kind of muscle memory linking their stage movements to their lines.

Time to hit the road.

“C.P. Air,” intoned an announcer in one skit, while a spastic pilot strapped in a wheelchair and his blind co-pilot, both in stiff-brimmed caps and flight jackets, smile and wave, “We might get you there.”

Or an alternate-world kind of setting, where a young woman in a wheelchair brings home her boyfriend, who receives an icy reception from her all-disabled family because he lacks a disability himself.

The show got a better response than even we had hoped.

Then, complications. On the day of the fifth performance, Joe, the blind actor, was in a minor car accident. (No, he wasn’t driving.) The same week, one of the expected grants did not come through. Suddenly the company faced a serious money shortage. Joe, married and with a mortgage, needed more stability and left the company.

What to do? In a few days Rolling Thunder was expected in northern Ontario, then Ottawa, and soon there was the statewide health conference in Indianapolis. If we stopped the little momentum Rolling Thunder had going, it may never be recaptured.

Fortunately the company was based at, and partially backed by, Participation House, a residence for physically disabled adults, so Thunder didn’t face eviction. As for the actors, they qualified for unemployment insurance and agreed to carry on. Me? My contract was done, but I knew the play and the role. It wasn’t like we could parachute a new blind actor into the role and expect him to work for free. So, for the length of each show, I became blind. Performance fees would go toward covering expenses. Onward, sort of, we rolled.

In some places, it was like the circus had shown up. One time in a northern Ontario town we went out for dinner at a pizzeria . The woman who owned the business began staring, it seemed, before we even got out of the van. The staring continued as we studied the menu, the woman frozen behind the counter, a pizza in front of her waiting to be dressed. The staring intensified another few degrees when the garlic bread arrived and Vicki, in a manual wheelchair, began feeding her husband Desi, who was strapped into an electric wheelchair, his legs twisted, his arms jumpy and his speech very limited. (One of the words he could say, his eyes brightening as he persuaded it up his throat, was “bugger.”)

Soon the woman sent her daughter over to our table with souvenirs from the pizzeria—hats and pens and keychains. A short time later she sent her daughter over again, this time to get our addresses. Her mother, the daughter explained, wanted to send presents at Christmas. Each time the daughter came to the table she spoke to me, the “safe” non-disabled one.

Empathy, pity, fear. The mother’s response was a complicated brew, though her intentions may have been good. A person with a disability, every day, faces extra attention and assumptions about intelligence and abilities. A person gets used to it, and, in other ways, never gets used to it. Assumptions, unchallenged, can stiffen into beliefs.

Driving back to our hotel the van was quiet until Jim commented, “I see we didn’t make her sad enough to pick up our fucking bill.”

Laughter. Though not right away.

❦

A nugget that revealed itself early on in the touring: Jim couldn’t eat before performing.

The act of digesting, when combined with the stress of being in front of an audience, stole too much of the fuel he needed to propel and navigate his way through a skit. All that lifting and setting down of those crutches. Confusion would skitter across his face and lines of dialogue go missing. Suddenly he was addressing another actor as Gus or Bud. There were characters with those names—just not in the skit he was doing at the time.

The rule became this: All food was verboten for the two hours leading to showtime. In the place of food, it was coffee galore. If we could have arranged an IV drip for Jim’s java, we would have.

By the end of the tour the following June the numbers were: 141 performances, five actors back on the payroll, one van engine kaput, and one narrow miss just outside Ottawa when a 4′ x 8′ sheet of plywood, part of our backdrop, tore free from the roof rack and went scything through the air, luckily veering off into a vacant field.

What I learned during my time with the company, 10 weeks becoming four years, continues to claim a prominent place inside me. Especially since that day in 1997 when the baby finger on my right hand began to twitch and Parkinson’s Disease introduced itself to me.

I often think of Jim—who passed away in 1990 at just 30 years old—and the others, remembering how they used humor and determination when their bodies, those unreliable narrators, didn’t go along with their instructions. So when my iffy balance interrupts and forces me to, say, take a knee in the middle of a grocery store, I wave off any and all helping hands.

“Don’t worry,” I tell them, “I’m already on my way back up.”

P.S.: The Christmas presents from the woman at the pizzeria never arrived.

Larry Brown lives in Brantford, Ontario. His short fiction has appeared in magazines across North America and in Germany. His story collection Talk was published by Oberon Press, and he recently completed Kurtin, his new story collection.

Rolling Thunder survived a few years after Brown’s departure, but the economics of keeping the company on the road, along with the difficulty of getting disabled actors to commit to uncertainty, a thing that bangs at them practically every day, eventually brought things to an end.