Eugene Lee, longtime resident scenic designer at Trinity Repertory Company and for NBC’s Saturday Night Live, who won Tony Awards for Candide, Sweeney Todd, and Wicked, died on Feb. 6. He was 83.

“There are hits, there are flops, people are born, people die.”

Anyone who has had the honor to collaborate with Eugene Lee can delight in this wise quip, spontaneously delivered in his unmistakable voice.

For 25 years, as Eugene’s friend, colleague, and mentee, I’ve been known to playfully distort my vocal cords to imitate his kooky sensibility and insight when I am seeking inspiration. What would Eugene do? I expect to ask myself that question for the rest of my life, as I strive to grow and collaborate on my future endeavors. Luckily I have countless conversations and stories to reference, each a lesson and a mystery, and his passionate can-do spirit to guide me. To say that Eugene was a genius is not an exaggeration. (I tend to be a straightforward guy.) Eugene’s gift was packaged in a complex and messy form that always relied on simple, real solutions, using real items. Eugene shared that he “always loved going to the dump as a kid. I love using real materials.”

In preparing to craft this tribute to Eugene, I rifled through my personal copy of his unpublished, never-finished autobiography. I’ve seen various versions over the years; the latest copy is a spiral-bound hard cover secured with a button and butcher’s twine tied in a sailor’s knot, a nod to his lifelong passion for wooden sailboats. Titled The Adventures of Eugene Lee, it’s an inspiring, bulging 375-page scrapbook of photos and typewritten stories, navigating in no apparent order the path from birth to his most recent project. Eugene’s stories always served a purpose; though they may have followed an indirect path and the message was not always immediately clear, I found I would always gain an insight if I really listened. (That may be one of my gifts: understanding him.) As he joked, “You can never learn less!”

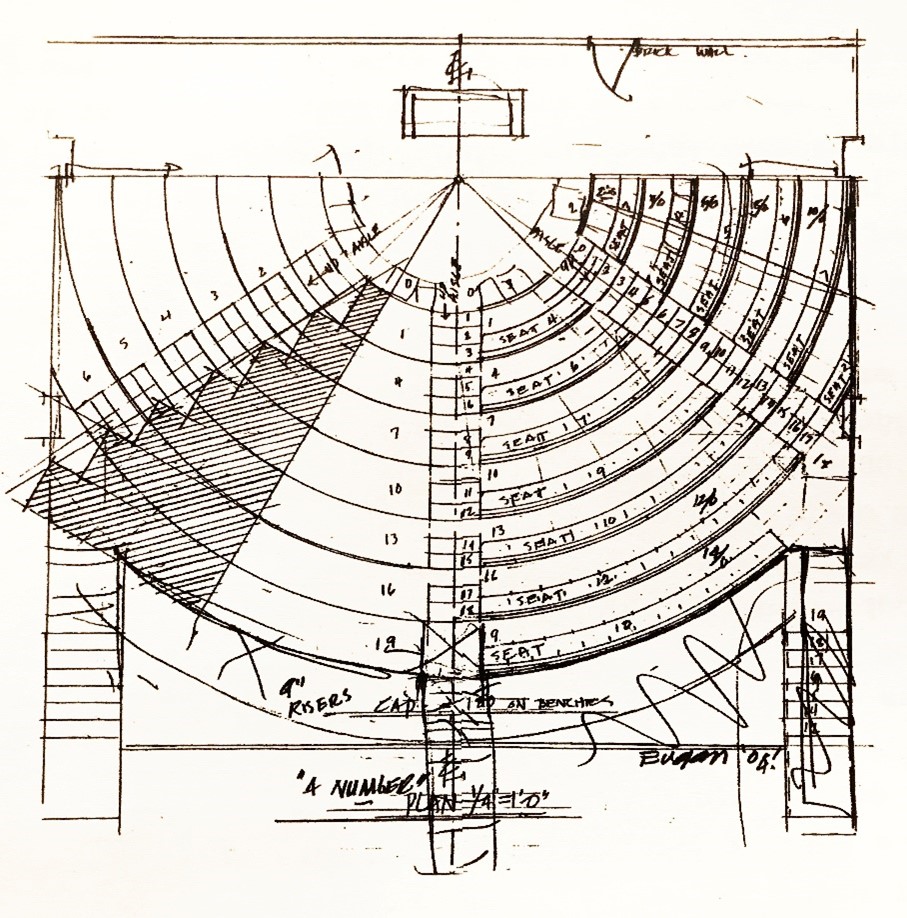

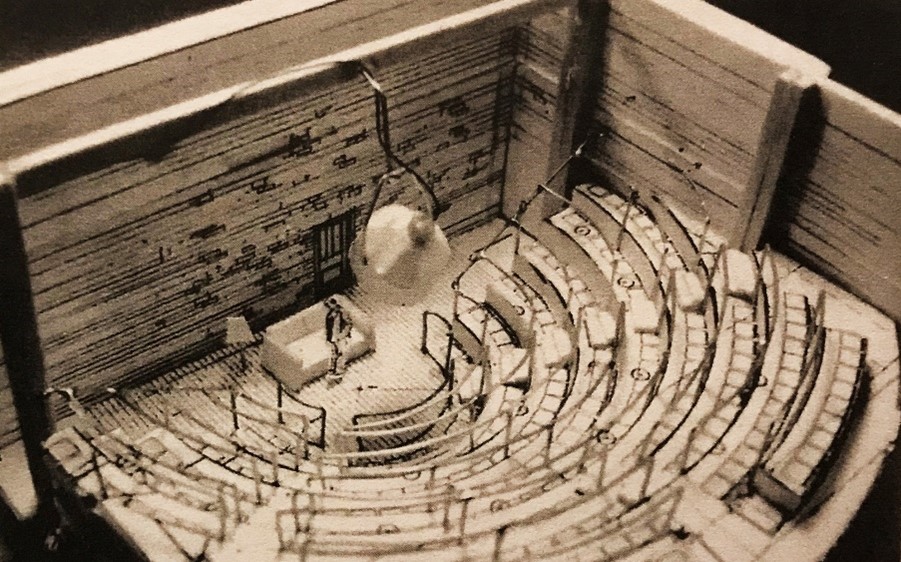

The first thing Eugene always focused on was the relationship of the actor to the audience. “I always feel more at home when the actors can touch the audience and vice versa,” he writes. Finding or reconfiguring a space to serve this relationship and to support the story is fundamental. I’m sure many theatre managers can attest to the challenges (and payoffs!) of reconfiguring their stage and seating to support his vision. Eugene: “Actors are always more important than the scenery. Scenery is highly overrated!”

Oskar Eustis, in his contribution to Eugene’s book, sums it up best: “Eugene often says that he hates scenery, and it’s true: What he loves is theatre. And making spaces where theatre can happen is his genius and passion. He’s a man of many contradictions: an old hippie who loves joining elite New England clubs; a fiercely innovative artist who worships history; a wild experimentalist who has made his living in television for nearly 50 years; a dedicated nonprofit theatre worker with a shelf full of Tony Awards; a committed avant-gardist equally committed to telling a story that anyone can understand. These intense contradictions have led to an utterly original designer who has worked successfully in more venues, mediums, and aesthetics than any scenic designer in American history. They also make him a wonderful collaborator…Once you’ve worked with him, it’s hard to stop.”

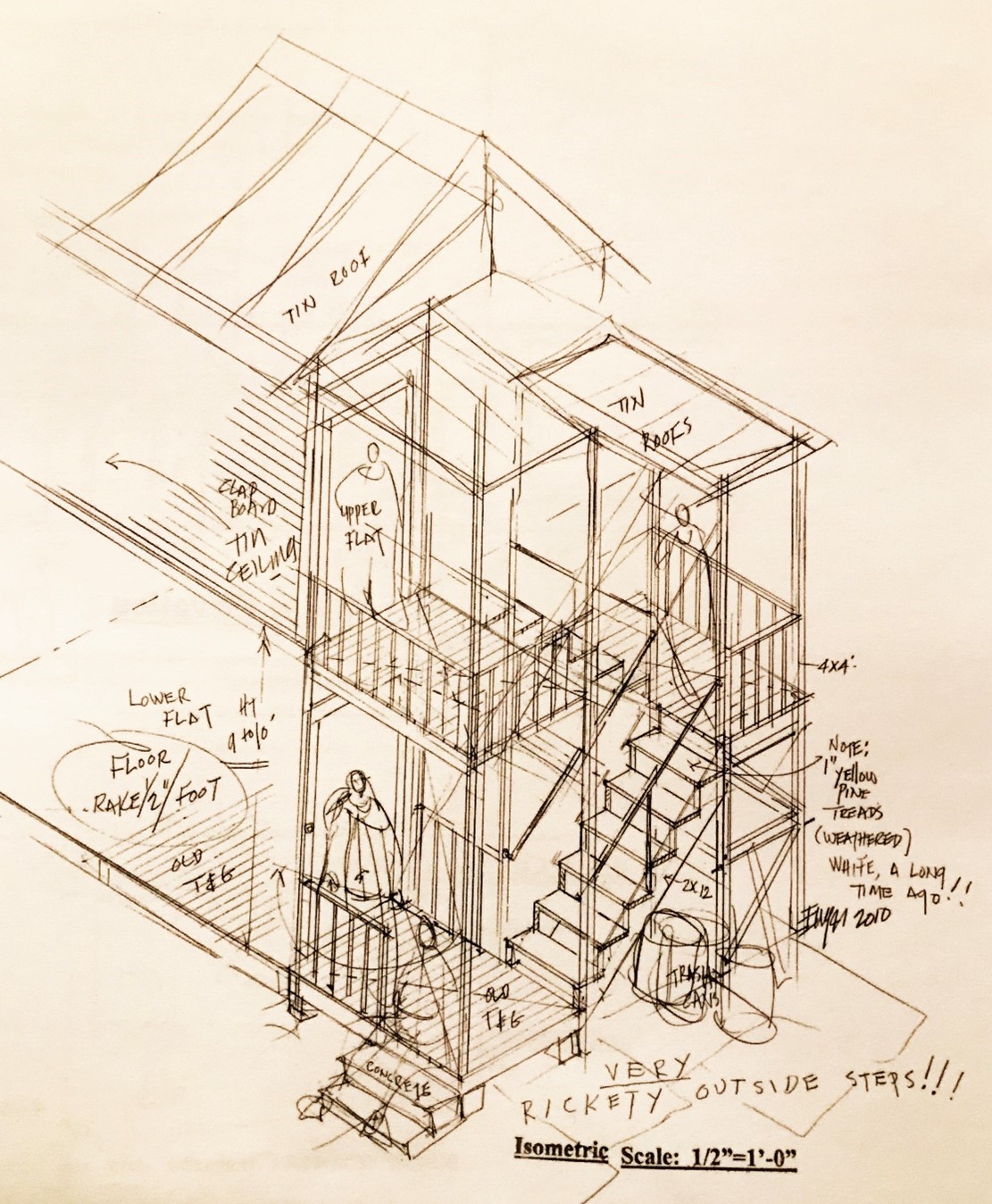

For most of my collaboration with him, Eugene and I worked remotely, communicating through hand-drawn drafts, messy models, and long phone conversations. During formative moments of a new project, I’d make a day trip to Providence to his grand Angell Street home and join him in his design studio above the carriage house, which has a little turntable built into the floor. Eugene was a photogenic fella, reliably dressed in khaki pants with a jacket and bow tie, his face framed by his elegantly circular eyeglasses. (“I love circles. My glasses are circles. All my cars have circular headlights.”) Eugene preferred a consistent schedule: “Every morning I wind the two clocks…In the winter I startup the coal stove; pretty soon the place is nice and warm. It is a nice dry heat. I start work around 9 and usually work until 5, without lunch.” Well, I can’t go the whole day without food, so Brooke (Eugene’s wife and the secret sauce behind the scenes) would always coordinate a lunch break on the back patio. It wasn’t easy, but Eugene would succumb to a grilled cheese sandwich on white bread with some potato chips and coffee. Now nourished, we’d be back to creating.

I will forever be in awe of Eugene’s ability to hand draft an expressive, accurately scaled drawing in a matter of minutes. Always at the ready in his chest pocket was a wooden hard lead pencil, which he would hold with his super-glue-encrusted fingers and create stunning isometric drawings, which he preferred. “You can measure from them, the isometric axes are true lengths, and they’re easier to understand than a ground plan. Directors can understand them.”

He’d always start with a model, kind of messy and playful, the kind he liked best. He’d then light them broadly and photograph them with his faithful Pentax 1000 (“It’s a very simple camera, no longer made”). He’d sometimes use a felt tip marker right on the photo, then print them using various speeds on the copier. He preferred black and white.

When we were ready to share our work and pack up the model, there was a vital ritual: “I take some white foam board and build my usual little box with a lid. I always build the model box the same way, with white glue and white tape. I always put a fillet of glue on the inside seam, and they never seem to come apart. I always tie down the lid with a piece of string made fast with a trucker’s hitch.”

On the final pages of Eugene’s book, he auspiciously transitions to: “The end of it.” On these pages, Eugene recalls an evening several years ago where he lay in bed sleepless, uncomfortable from recent double-knee surgery, kept awake by torrential rain and wind that shook the whole house. Searching for sleep, or perhaps peace, he accounted for his active projects and the nice people he was working with. He slipped deeper into rest, dreaming of his passion projects. (A pencil factory—that would have been cool!) Suddenly, the phone rang; it was Hal Prince. He wanted Eugene to design…Wait, is this a dream? Eugene’s eyes finally relax and, under shallow breath, he thanks Brooke, his sons, me, then sleep…sailing.

The final, forward-looking entry reads: “Brooke wants to take the dogs out for an evening drive, they expect it. Tomorrow, off to…”

Then and now, Eugene Lee is sailing off to his next adventure.

Edward Pierce (he/him) is a Tony-nominated designer who collaborates on Broadway, touring, and international live stage productions. He currently represents designers and artists as the president of United Scenic Artists, Local USA 829.