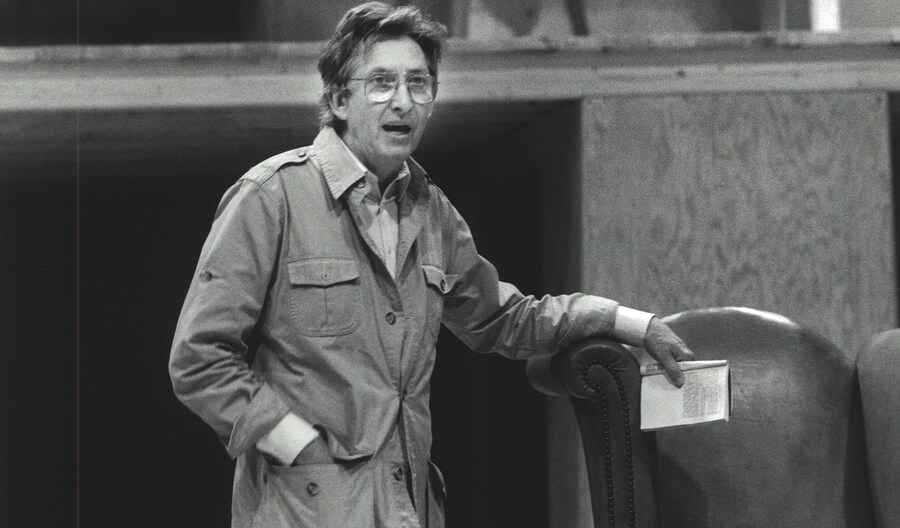

Adrian Hall, founding artistic director of Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, R.I., from 1964 to 1989 and artistic director of the Dallas Theater Center from 1983-89, died on Feb. 4. He was 95. This is one of two tributes to his memory; the other, by Anne Cattaneo, is here.

Every day I pass Adrian Hall Way on my walk to Trinity Repertory Company. The small street curves around the side of our theatre building in Providence, R.I., and it was named in honor of our founder who passed away at the age of 95 last week. I think of Adrian Hall each day, not only for reasons of geography, but because his influence continues to reverberate in our theatre, and throughout the American theatre more broadly.

Adrian was a visionary, a groundbreaker, a disruptive-artistic-community builder. He could be mercurial, bawdy, petulant, and grand. But the story of Adrian Hall’s singular genius is not a solitary story. He naturally collected artists around him, always travelling with a tribe of fellow theatremakers, and so his story is one that includes so many others.

Adrian built Trinity Rep with the idea that a resident company of artists was central to a great theatre. With that initiating idea, great actors came to live and work in Providence—Katherine Helmond, Richard Kneeland, Barbara Meek, Blythe Danner, Richard Kavanaugh, Ed Hall, Richard Jenkins, Peter Gerety, Rose Weaver, Ricardo Pitt-Wiley—the list goes on and on and on. Viola Davis, who grew up coming to Trinity’s shows, wrote about Adrian’s passing: “I became a professional actress at the age of 23, acquiring my Actors Equity Card [at Trinity Rep] because of this brilliant artist. Thank you for seeing me, Adrian.”

Richard Jenkins, who joined the company in 1971 and lives in Rhode Island to this day with his wife, the choreographer Sharon Jenkins, served as artistic director of Trinity from 1990 to ’94. “The luckiest day in Sharon’s and my life was landing in Providence in 1970,” Jenkins recalled, “and beginning our journey with the astonishing Adrian Hall and his brilliant designer, Eugene Lee. They taught us everything. From blood balls in Troilus and Cressida; hacking a side of beef and a floating boat with no water and no boat in Brother to Dragons; dancing mice in Inherit the Wind. These were just a few of the images that changed the theatre from a passive pageant to a vibrant, visceral experience.”

Adrian’s aesthetic genius was developed in seamless tandem with the peerless designer Eugene Lee (who died less than 48 hours after Hall did, and is equally missed). That aesthetic focused on what was theatrical, not filmic, and on how individual, visceral gestures could evoke the range of human experience. The “side of beef” Jenkins references was hacked in close proximity to the audience, spattering them with blood, in a play about the 1811 murder of a young Black slave by Thomas Jefferson’s nephew (based on Robert Penn Warren’s poem Brother to Dragons). Adrian knew how to explode an image in the hearts and minds of an audience while taking them on powerful, profoundly human theatrical rides.

Stories abound at Trinity about the work Hall did that revolutionized our theatre and the audience in Rhode Island. Project Discovery, the 58-year-old education program at Trinity, was built on the idea that adult shows would be performed for student audiences. Once, when Hall staged an adaptation of Melville’s Billy Budd on a wooden sailing ship in the RISD auditorium, the great Barbara Meek delivered a long monologue at the top of the show. Student audiences talked and laughed, generally inattentive to what Barbara was saying. This infuriated Adrian; he said, “Roll out one of those cannons and fire it at the little fuckers. That will shut them up.” They rolled out the cannon and fired it. The students screamed and laughed…and then fell silent. That awareness of the audience and its experience became central to the “Trinity aesthetic” that Hall and his collaborators created.

There was also the time (so the story goes) that Adrian built a tent in the street next to the theatre (in the aforementioned way that would be named for him, actually) and filled it with a live band and people serving beer to the audience as they arrived. People were having a wonderful celebration, with actors all around them and alcohol flowing. Then they made their way through the lobby of the theatre, which had been turned into a midway, complete with bizarre carnival games. It was only there that audience members began to realize the antisemitic nature of some of the games, as they were funneled into the main performance space. There, all of the seats had been torn out, forcing them to stand and watch as a middling little man climbed to the top of rolling platforms and was transformed from a pointless bureaucrat into Adolf Hitler. The play was Cathedral of Ice. It was this kind of powerful message, viscerally delivered, that was always central to Adrian’s work.

And what a message! Hall’s theatre dealt head on with abortion rights, with homosexual relationships, with the legacy of slavery, with fascism and the precarious nature of democracy…and this was the late ’60s and early ’70s! Adrian was an out gay man running a public institution when his sexuality was still widely criminalized and pathologized by the mainstream culture. He catalyzed conversations about race and gender at a time when most theatres were only beginning to undertake such conversations, if they did at all.

Perhaps his most lasting legacy is that of a public intellectual, someone who encouraged the community around him to engage in robust democratic dialogue. Providence and Rhode Island still feel the pulse of the conversations that Adrian started more than 50 years ago. When I asked Oskar Eustis, my predecessor as artistic director at Trinity, what I should write as a tribute for Adrian, he said: “Adrian Hall was an artistic giant among a generation of giants, the founders of the American nonprofit theatre. Along with Zelda Fichandler, Gordon Davidson, Margo Jones, Bill Ball, Nina Vance, and Joe Papp, he carved out a place for serious theatre art from the often-resistant American soil.”

We continue the work that Adrian began. His story, which is one of an individual kind of genius working in a collaborative form, is carried on by so many of us. And I will take heart every day, when I pass Adrian Hall Way, knowing that so many others have followed his way as well.

Curt Columbus is artistic director of Trinity Repertory Company.