Anyone paying attention may notice that Asian American theatre is both under intense duress and going through a kind of renaissance. KPOP, only the second Broadway musical with cast and creators of nearly all Asian descent, was originally lauded as a groundbreaking production only to be closed unceremoniously early shortly after an equally unceremoniously culturally and racially insensitive review from The New York Times. At the same time, in the last year, many Asian American playwrights, performance artists, and creators are enjoying more critical visibility than ever: from Kristina Wong’s Pulitzer nomination and string of regional theatre productions for Kristina Wong: Sweatshop Overlord, to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) being honored with a Tony for excellence in theatre to sold-out showings of Lloyd Suh’s The Chinese Lady at the Public and other regional theatres.

Such tenuous standing within theatre for artists of Asian descent reflects a larger trend by which we are seen as both foreign but exemplary, desirable but contagious, or, as historian Erika Lee (echoing a book by Shankar and Srikanth) calls it, “a part and apart.” Milestones in Asian American Theatre, a new anthology edited by veteran theatre scholar Josephine Lee, offers a vital, easy-to-read primer on how we arrived at this moment. This svelte, economical volume should be required reading not only for theatre students but for artists and producers as well.

Published by Routledge, the Milestones series of textbooks are designed to be accessible explorations of important social and cultural topics. This volume was intended as part of an introductory 10-week course on Asian American theatre. Speaking as someone who has taught an Asian American theatre course at the college level for several years, and has had to piece together material from the late 1990s and early aughts (including Josephine Lee’s important first book) with more recent articles and my own research, I can say that this book just made preparing for next semester much more straightforward for me, and should do the same for my colleagues who teach theatre and/or Asian American studies.

I must emphatically stress, however, that this book should not be relegated to the classroom. At 274 pages, including references and indexes, the book covers much ground with few words. It defines important terms for those new to either Asian American history or theatre, and offers additional resources for every chapter. In other words, the whole volume provides many ways to extrapolate its material into further specific topics or shows. Any producer, director, dramaturg, or playwright who wishes to work on an Asian American show or with Asian American materials and characters in the future can turn to this as a reference volume—not to provide the entirety of information a production might need, but as a way to find appropriate resources for a project, ensemble, or company. Indeed, with many predominantly white institutions trying to address the heightened calls for racial equity in season programming, Milestones (and perhaps others in the series) constitutes a very simple introduction to a vast and significant body of theatrical works that remain under-studied and under-produced.

The 10 “milestones” of the title are arranged in loose chronological and topical order. They include a look at plays centered on Afong Moy, the historical “Chinese lady” who was paraded before U.S. audiences in the 19th century; histories of exclusion and the “yellow peril,” and plays around nationalism; theatrical interpretations of U.S. imperialism in Hawai’i and the Philippines; dramatic explorations of Japanese American internment; the complexities of post-1965 immigration, the model minority, and masculinity in Broadway and Off-Broadway productions; Asian Americans in performance art and the avant-garde; plays covering Southeast Asian experiences of war, relocation, and memory; yellowface; racialization and representational resistance among South Asian, Muslim, and Arab Americans in the wake of 9/11; and the lost season of 2020 and its ensuing depictions of illness.

Milestones first delves into the complexities of Asian American history and politics. ”Asian America” is contested; our whens, wheres, whats, and whys differ vastly. From the first recorded people of Asian descent in Louisiana during the 1760s to the present, waves of migration span the duration of the U.S. nation state. We are from East, Southeast, and South Asia as well as the Pacific Islands and areas of West Asia often referred to as the “Middle East.” We have been indentured servants, migrant laborers, refugees, physicians, or venture capitalists. We came seeking work, asylum, education, fortune, or stability.

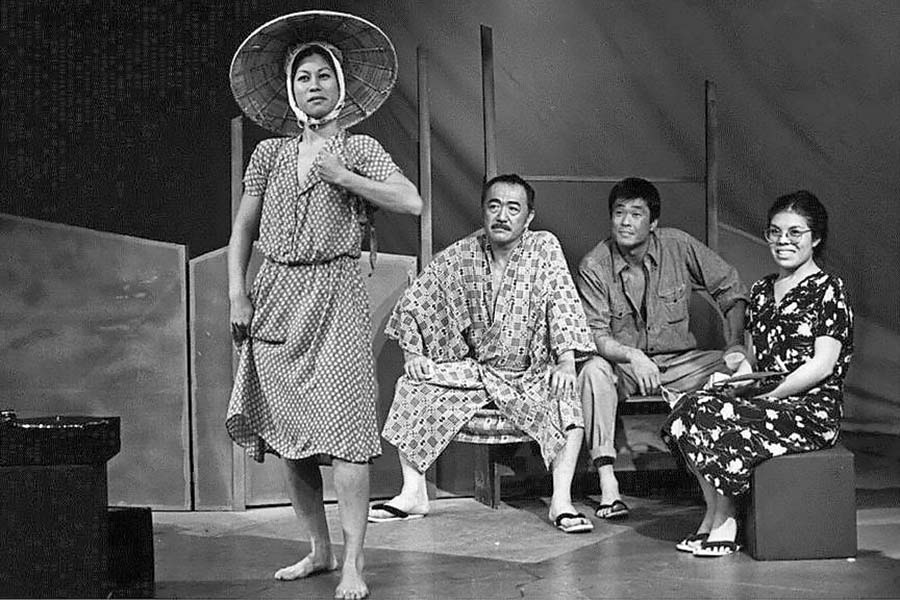

Meanwhile, Asian American theatre has been one place where people of varied Asian descents find strategic and fruitful alliance. While Milestones explores this history and the concomitant theatrical texts written alongside and in response to those histories, it also provides a much-needed history of Asian American theatre organizations, including organizations in larger coastal markets such as East West Players, Pan Asian Repertory Theatre, and Ma-Yi Theater Company but also organizations such as Hawai’i’s Kumu Kahua Theatre, Chicago’s Silk Road Rising, and Minnesota’s Pangea World Theatre and Theater Mu. These organizations not only have produced Asian American plays for decades; they have also grown Asian American talent from the ground up. Many renowned Asian American actors, playwrights, directors, and designers received their first major gig or commission from such companies, and such companies constitute a network of mentorship that becomes clear in the complex web drawn throughout the book.

Any shortcomings I could point to in Milestones are rooted in the brevity that makes it such an accessible volume. Inevitably, things get left out. And I would guess that any of the clearly conscientious contributing authors would be scandalized at the hubristic thought of creating an exhaustive or definitive single volume. With the explosion of plays coming from all communities of color, the book was bound to be already obsolete (despite covering shows up through fall 2021) before it hit the presses.

All that said, I would have loved to seen more about South Asian history and theatre artists throughout the book, even if the post-9/11 chapter does provide much context. In addition, we all have our biases; in my case, I was surprised to encounter little analysis of work by Young Jean Lee or Rajiv Joseph—playwrights whose work has gained wide recognition that could benefit from more context.

These minimal critiques, though, pale in comparison to the immense contribution to theatre and education Milestones clearly makes.

Nearly every Asian American theatre artist I know can recall the experience of being “the only” one of Asian descent in a given rehearsal room. Theatre training and history for people of Asian descent has often relegated Asian Americans to supporting roles, both onstage and off. Meanwhile, the Eurocentric American appetite for the “Oriental” as separate from Asian bodies or experience has fostered long-standing depictions of stereotype, often performed by white people in the form of yellowface and brownface. Even now in many parts of the country, yellowface and brownface performances cross educational and professional stages often, with critiques refuted by claims that producers simply “could not find” talent of the appropriate race or ethnicity.

Milestones painstakingly outlines the resilient presence of Asian American theatremakers across the country throughout the decades, in sometimes surprising cities and markets, making it clear that claims of scarcity in performing or creative talent cannot excuse the lack of effort or imagination on the part of producers and institutions. Among other achievements, this Milestones volume should put that misconception to rest.

Writer kt shorb (they/them) is also a director, scholar, and performer.