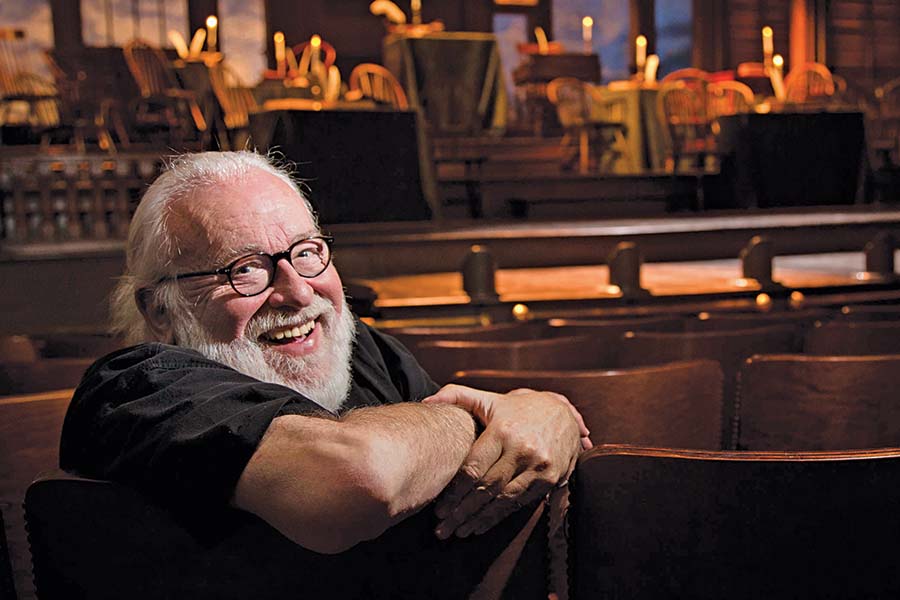

Director, writer, performer, and teacher Frank Galati, a longtime member of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company and professor at Northwestern University who won Tony Awards for directing The Grapes of Wrath and Ragtime, died on Jan. 2. He was 79.

Once, at rehearsal, an actor approached Frank with a lot of new, perhaps slightly crazy, ideas about his character and what he should be doing in that quiet moment of the play, which was, he thought, to be suddenly very loud. Frank listened intently, his brows concentrated, his eyes shifting this way and that, illuminated in thought. “Yes, yes,” he said, nodding slowly. “Yes, I see. Oh, yes!” And then he said, “And you know, Steve, the opposite is also true.”

Later in life, Frank told me he had stopped giving any critical notes whatsoever, because actors always self-corrected. I don’t know if this is true, but I do know that when he gave individual notes, he was multilingual: He spoke to each performer in the language of their unique sensibility and method. So to one he’d say, “How are you feeling about that moment when you stand and…?” and then, after several minutes of intimate and detailed discussion, turn immediately to another and say, “Act 3, sc ii? Faster.” His notes to the general company were, broadly speaking, rhapsodic. Utterly possessed by his love of the complex act of theatre, its secret codes and systems, its ways of making meaning, and above all, the text itself (which to him was a living presence of greatest possible treasure), he cast a spell—if spells can be said to consist of relentlessly original, insightful, and accurate observations, perfectly stated. Often there were tears. Frank was weepy. I’m weepy like that too. Especially now.

When I was 18 years old, in my first year at Northwestern, I saw Frank walking to class in the rain. He was a large man, particularly relaxed around the shoulders, with a forward gaze that seemed to be directed simultaneously outward and in. Against the rain, he was carrying a yellow umbrella meant for a child, only about two feet in diameter, with a bright red handle. What would my life have been if he hadn’t, from that moment to this, been my professor, director, eventual co-teacher, singular witness to my work, and the absolute pattern of an artist and a human being that I longed to be? It’s unimaginable. Back then, someone told me that he once said of me, “With that one, it’s all ardor or contempt.”

Slowly, among all the things I learned from Frank (that is, everything of importance that I know), was the understanding that the true mark of sophistication in response to performance is enthusiasm. Not cynical dismissal, but enthusiasm. Not the childish eyeroll, not the ability to find fault, but rather to find beauty. If the attempt was sincere, no matter how flawed or banal the result, Frank could find the flecks of gold amidst the sawdust of any performance. Whether in a freshman class or on the stage of the Lyric, he could feel the ardor—because, in its attempt to capture something of the fleeting world, all performance is devotional.

Here are some other things I learned from Frank:

- Use the depth of the stage more than the width, because that creates a simultaneity of perception rather than a sequence of perception; rather than invite a reading across the surface of the image, it lures the eye deeper into the image, and therefore into meaning.

- Say almost nothing in response to the actors’ first attempts at a scene; don’t cover them up with words, never make them think they are in error.

- When people are upstage, it implies they are not only distant in space but also in time, because “they are smaller.”

- It’s not an accident that the expression is to know one’s lines “by heart.”

- Theatre is the living manifestation of metaphor: This stands in for that. And this is particularly critical when the source text was not conceived for the stage and its limitations; then we must use all our cunning.

- Always insert something of the beginning in the end.

- Always smile during the curtain call, because it is a symbol of the Resurrection.

- About death he once said, “Why is everyone always wondering what it is like? We know what it is like. We’ve been dead already. We were dead before we were born. It’s just like that.”

Frank was a genius, and he was hilarious. He was our philosopher king, for whom understanding why the thing worked was more thrilling than that it did work. He was the most astute reader of text, performance, and people that I’ve ever known. His creative energy as a director and writer was relentless; as an actor he was eccentric, florid, riveting. His generosity was preposterous, his casting prescient and inclusive, his contribution to the American theatre, particularly in the realm of adaptation and staging, profound.

Nothing I can say here can adequately capture the life force and beauty of that man and his work; but, like the penultimate image of his Grapes of Wrath, where Rose of Sharon nurses a starving man as rain pours down in sheets behind them in the huge opening of the barn doors, it is indelible.

Attentive as we are, and should be, to every member of our audience, I believe we all make our plays for just two or three people: the only witnesses whose opinion, whose witnessing, matters. And it makes no difference if that person is no longer alive; we go on making and shaping everything under the thought of what they might think or feel or say of it. I know that when looked at that way, it doesn’t matter that Frank will never actually see another show of mine or any of ours; that we will never again return home to an eight-minute phone message from him, rapturous and luminescent. I know we all live on in each other and in our work. I know, as Proust (who Frank loved) wrote, that “nothing is ever lost; the missing jewel always turns up again.” So I know we will all be fine and carry on.

And I know that the opposite is also true.

Mary Zimmerman is a writer and director of theatre specializing in the adaptation of classic stories of world literature for the stage. She teaches in the performance studies department at Northwestern University.