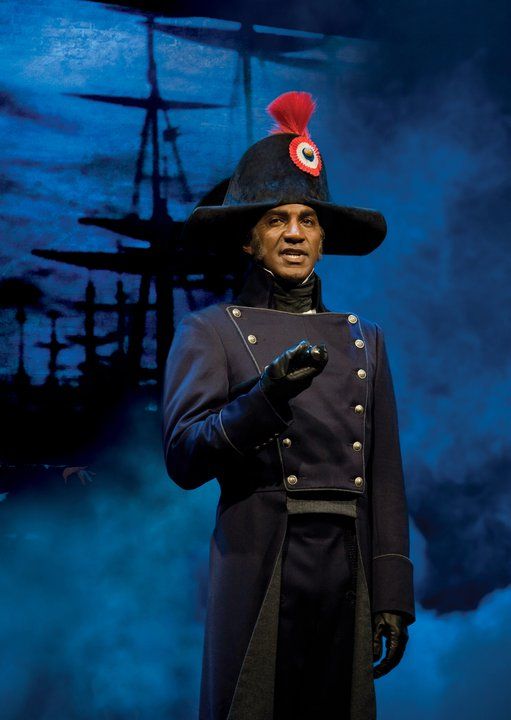

Versatile actor-singer Norm Lewis, who headlines the cast of the Roundabout Theatre Company’s national touring production of A Soldier’s Play, seems to move effortlessly among musicals (Les Misérables and The Phantom of the Opera on Broadway, Sweeney Todd Off-Broadway), straight dramas (The Tempest for Public Works), and stage comedies (last season’s Chicken and Biscuits). With A Soldier’s Play, which closes its Washington run at the Kennedy Center this week and next appears in Charlotte, N.C.’s Knight Theatre (full schedule here), he is taking on a meaty role in one of the great 20th-century dramas.

In Charles Fuller’s play, set at a segregated U.S. Army military base in Louisiana during World War II, Lewis plays Richard Davenport, a resolute Black Army captain, sent to investigate the murder of a polarizing Black sergeant, who in his pursuit of the truth unravels a web of racism and colorism against a background of tradition and culture, sacrifice and service. The piece won Fuller the 1982 Pulitzer Prize for drama after its production at the Negro Ensemble Company and Off-Broadway. That was followed by an acclaimed film adaptation, A Soldier’s Story, and finally, a belated Broadway debut in 2020, with Blair Underwood in the Davenport role. The tour kicked off last Dec. 13.

“This is something I never even thought I would be a part of,” Lewis, who is 59, said in an interview. “I’ve admired the work, loved it, thought it wonderful, but it was just never on my radar to do.”

Since booking the show last summer he’s immersed himself in the script, which features three major monologues from Davenport and covers fraught emotional terrain.

“There’s a lot I have to ingest,” he said. As with all roles, he said, “I try to figure out what the author is talking about and then I bring in things I’ve experienced in my own life to the character. You have to bring yourself to make it your own.” Lewis is especially struck by the way that Fuller was unafraid to explore “the dynamics within our race. He created such an amazing piece of history through art.”

Though he may be best known in the theatre for his work in musicals, Lewis brings dramatic craft to that work as well.

“When students do a song in master classes I teach, I make them do it as a monologue first,” Lewis said. “That way they understand the words and subtext, instead of getting locked into the melody. And then they go, ‘Oh, wow, I just found something new—I didn’t realize that’s what that was.’ Sometimes you get so caught up in the beauty of how it sounds instead of what it actually means.”

For Soldier’s Play director Kenny Leon, Lewis’s unique magnetism is what makes him a match for the role.

“Norm has a kind of presence and charisma onstage unmatched in the American theatre,” Leon raved. “I’m trying to dig into that and tie that to Captain Davenport—someone who loves his country, loves his culture, and can take us through this play. That’s Norm.”

None of this would have happened for the Florida native if he hadn’t moonlighted as a singer from his full-time job selling ads in the Orlando Sentinel. Singing was always part of his life, starting in church. “It was what I was supposed to do every Sunday: Go to church, praise the Lord, make a joyful noise. It wasn’t heart-driven. I wasn’t dying to be that performer guy, because I didn’t think I was good enough. It was just fun.”

A competitive athlete from childhood, he played team sports but eventually turned his focus to tennis. “Tennis was my passion,” he recalled. “I really wanted to be a professional player.” This was after Arthur Ashe’s death and decades before the Williams sisters, meaning there were few Black tennis stars to emulate. When that path closed, he attended a small liberal arts college in Florida, and later took an advertising day job while going to open mics as a singer at night.

“I guess in the back of my mind I wanted to be a performer,” he recalled. It was an open mic contest at a local bar that gave him his big break. “You could win money or a trip; sometimes I’d win, sometimes I’d lose. But this particular time I won, and the producer of a Premier cruise ship show was a judge. He said, ‘I need someone on the ship like you, would you want to do this?’ That’s what propelled me into this world.”

Performing on a four-month cruise to the Bahamas and back was all he needed to change course. Not long after, he made the leap to New York. He was nearly 30. Family and friends were taken aback.

“Showbiz was just not part of my world,” he said. “They were like, ‘What happened? We knew you sang at weddings and at bars, but…?’ So, yes, they were very shocked.”

Before long he booked his first tour (Once on This Island) and his first Broadway role (The Who’s Tommy), and silenced the doubters.

“One of the best pieces of advice I give aspiring performers is believe in something, namely yourself,” Lewis said. “There’s no rulebook on how to be in this industry. I have so many friends that have come into this world in weird ways. And now you have reality stars.”

As a Black stage artist based in New York, Lewis has been part of the reset the theatre field has been undertaking in response to increasing calls for greater diversity, equity, and inclusion. In 2020 he joined the likes of Audra McDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Kenny Leon, Capathia Jenkins, Wendell Pierce, Anna Deavere Smith, Vanessa Williams, and others to create Black Theatre United (BTU). The co-founders bring a gravitas and responsibility to the work, having already broken ground for Black theatre artists; Lewis himself made history playing Javert in Les Misérables and then the title role in The Phantom of the Opera.

“In the wake of George Floyd, it just became a necessary thing to speak out about injustices,” Lewis said. “We decided to create a coalition to make things better. We have a mission to bring equity, diversity, and inclusion into the theatre, not only onstage but behind the stage as well.”

BTU centered conversations around these topics by convening an online summit in the spring of 2021.

“We had theatre owners, producers, directors, union leaders participate,” Lewis said. “Instead of pointing fingers in people’s faces and saying, ‘You have to do this,’ we said, ‘Let’s have a conversation and understanding between us.’ So many people talked freely and openly about how they felt about what was going on. We’re going to do that again.”

That summit produced the New Deal for Broadway, a signatory pledge around equity and inclusion. Producers and union heads weren’t able to agree to everything, but, said Lewis, “It is just the beginning of the conversation to hold people accountable for certain things that need to change.”

Initially, Lewis said, pursuing roles traditionally cast with white actors was just about landing coveted parts. But he’s come to recognize a greater significance.

“There are few of us, especially in my age range, that could have done that—I was just lucky enough to be that one chosen,” he said. “It meant more to me after the shows, when I would see people backstage from different countries and they would say things like, ‘Oh, now I can see myself doing the role.’ It’s definitely about representation.”

In A Soldier’s Play, though, he’s representing more than just himself. As with any period piece about the African Americans—he originated a role in the antebellum-set musical Dessa Rose—the mandate is “to honor the ancestors. Because of their struggle, I am where I am right now. You try to bring the authenticity and the truth and the strength of who they were.”

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance writer and the author of the 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.