The moment that seemed like it would launch Miami theatre artist Teo Castellanos into the world turned out to be the one that kept him at home. He was performing his first full-length piece, N.E. 2nd Avenue, a multi-character solo show of only-in-Miami personalities, from a Haitian jitney driver to a Cuban rafter, at the 2003 Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The show had been a hit back home. But in Scotland, an increasingly despairing Castellanos faced an empty theatre each night. When he ran into a group of visiting Miami students from an arts program at a predominantly Black high school, he pleaded with them to come. They filled the house that night, screaming with delight and recognition at seeing people they knew onstage.

In their midst was Edinburgh’s leading theatre critic, Mark Brown of The Scotsman, whose rave review called N.E. 2nd “so brilliantly conceived and so fabulously acted that it goes instantly to the compartment of the brain marked ‘reasons I go to the theatre.’” His praise led to a sellout run and a prestigious Fringe First Award.

It also convinced Castellanos to double down on telling Miami stories and helping more young people like the ones who’d borne him up that night to find their creative way.

“I love my people,” Castellanos recalled of that moment. “I made the decision not to go to L.A. or New York but to stay and cultivate the scene here.”

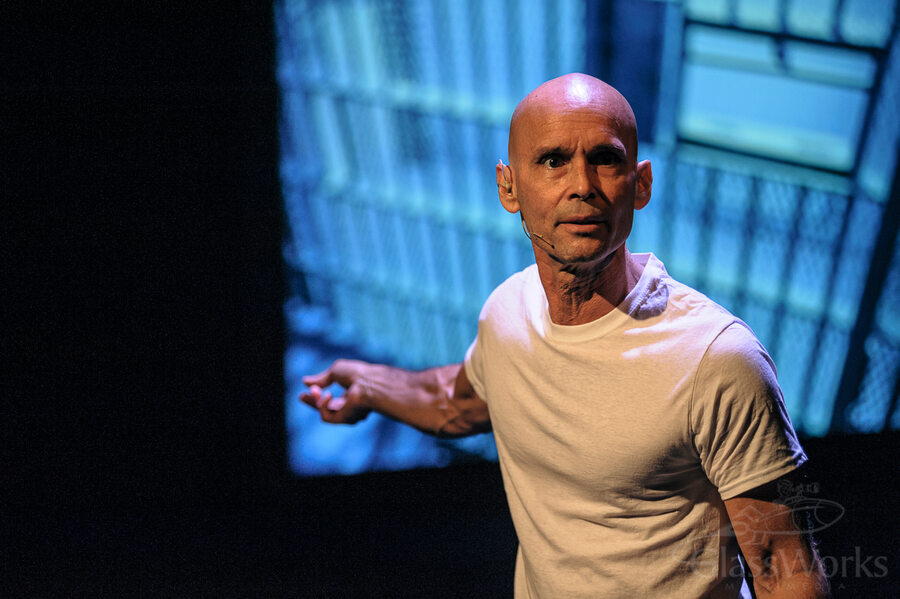

Teo Castellanos may be Miami’s most transformative theatre artist. He has empowered generations of Black, Latino, and socially or financially disempowered adolescents, like he once was, to tell their stories via theatre, poetry, and performance. He has devoted painstaking years to teach everyone from hiphop b-boys to combat veterans how to be theatre artists. His solo and group devised pieces, from N.E. 2nd to last October’s F/Punk Junkies, which channeled Afro-Caribbean myth and raging punk spirit, have given voice to the unique culture of this immigrant-shaped city.

Castellanos is neither well-to-do nor well-known outside a relatively small circle of mostly Miami-based theatre and contemporary performance artists and the institutions that support them. (He was a 2021 Doris Duke Artist in theatre and a 2019 United States Artist Fellow.) But he has lived, is living, exactly the life he wants.

“My dreams have become reality,” Castellanos, 60, once told me. “I never equated success with becoming rich and famous. I did equate it with forging my own path, creating my own life and lifestyle, doing what I love, and loving what I do.”

His most famous student, Tarell Alvin McCraney, chair of the Yale School of Drama’s playwriting program, sometimes wonders which of them got it right.

“As kids we wanted to get out of Miami,” McCraney said from his Yale office. “Teo said, ‘You’re letting people fool you out of paradise.’ ”

Miami wasn’t paradise for Castellanos at first. His family moved here from Puerto Rico when he was 6, and he grew up in Carol City (now Miami Gardens), then a notoriously violent area divided between Blacks and Latinos. (“Sister city to the South Bronx!” he calls it in the autobiographical Third Trinity.) His single mother worked two jobs. Castellanos dropped out of school, got into drinking and drugs, and worked for years as a bus driver and supervisor. He exulted at balancing his straight job with getting high and maintaining a hipster night life: dancing at clubs, singing in punk and ska bands, going to gallery openings, attracting women.

By his mid-20s, drug dependency threatened to destroy that balance. But Castellanos stepped back from life on the edge. He got clean and sober. And something opened inside him. “All these feelings came up,” he told me for a 2005 story.. “One of the big ones was: I am an artist. I want to be an artist.”

He got a theatre degree from Florida Atlantic University in 1994, and bought the two-bedroom house where he still lives that same year, cultivating a lush jungle of a garden. His girlfriend Lorna Burke, who helped him get clean, became his wife of 32 years; their daughter Jaquen (a name they invented, combining Jamaica, where Lorna is from, and Borinquen, the Indigenous name for Puerto Rico), born in 1990, writes for TV in L.A. And he became a devoted practitioner of Zen Buddhism, which came to shape his life as much as theatre and teaching have.

His saga was enormously compelling. I’ve known Castellanos since he was a regular at a poetry night in a South Beach club in the late 1980s. Small, lean, his sleek head shaved, he was so lit then, he seemed electrified. As an arts writer at the Miami Herald, I wrote a profile detailing his journey “From the Street to the Sage,” as the headline put it.

But Teo is done telling that story. “I don’t want to focus on that at this stage in my life,” he said recently. “It’s irrelevant.”

What remains relevant is how driven he has been to create himself as an artist, and to give others the tools to find meaning and create community that he had to discover for himself.

Castellanos began inventing his own model of theatre as soon as he started studying. He was confounded and incensed that his college teachers pressed him to lose his accent, and that forms which were natural to him—hip-hop, improvising in a circle of peers, spoken word—were excluded. “This idea that you have to erase your culture, your upbringing, your ancestry, is ludicrous,” he said recently. “I was like, ‘This is not right! The ancestors in me are revolting.’ ”

He read Peter Brook, Augusto Boal, Grotowski, and Puerto Rican poets; researched African griots and pre-Colombian shamans, Theatre of the Oppressed. In retrospect, he sees that what he was trying to do was to decolonize theatre before that became a catchword. “When that word came out, I realized that’s what I’ve been doing,” he said.

He immediately integrated these ideas into teaching. McCraney was one of his earliest students, in a program Castellanos led from 1995 to 1999, for teens to write and perform pieces about drugs and AIDS in their Black and Latino neighborhoods. A counselor who knew McCraney’s mother was in rehab sent the eager 15-year-old to audition.

“Teo didn’t think I was very talented, but he saw my passion,” McCraney said with a laugh. He stayed with the program through high school at New World School of the Arts, Miami’s renowned public-school conservatory, and even through his first year at DePaul University. That experience molded McCraney as an artist and inspired his determination to foster dramatists from outside the mainstream at Yale who can speak for their communities.

“I call Teo my father in art,” said McCraney, who became a close friend and colleague to Castellanos. “I started taking my work as not just one portion of myself but my full existence. Teo knew that, like him, we needed the tools of storytelling and hope to understand the world of chaos we came from. We couldn’t lie. Those tools, that method, is always in my mind. If I’m doing a play and it can’t happen on those streets, it doesn’t pass the Teo test. It’s not authentic enough.

“I never felt like Teo was taking pity on us,” McCraney continued. “It was always, ‘I understand; here are some ways we can work through that.’ Teo made me the author of my own story. Teo says: Don’t just accept the dreams that are given to you.”

Castellanos has continued to teach similar programs. In 2014 I visited him as he coached students in WordSpeak, a citywide poetry program for high school students, for a national spoken word competition, which he did for nine years. Castellanos adored his students, many of them dealing with fraught families or neighborhoods.

“I’m just floored by their commitment and resilience,” he said. “I don’t know why some people are blessed with that and some are not.”

He was also meticulous and demanding. “Better impress me—let’s see what y’all got!” he exhorted a trio of young Black and Haitian men doing a poem on gun violence. He had them research and write poems on social themes: terrorism, disappearing languages. “They come to understand that the world is bigger than their community,” he told me. “It deepens their compassion and understanding.”

Mary Luft, whose nonprofit Tigertail Productions ran WordSpeak, said of Castellanos’s rapport with the students, “They believed in him. He had the ability to reach into their creative self and pull out the best of who they were.”

At the beginning of his career, Castellanos acted in local plays, and in TV shows and films (usually as a Latino thug). He found his métier in the late ’90s, when he began making solos for Here & Now, an annual festival of short original works produced by the nonprofit Miami Light Project. Artistic and executive director Beth Boone suggested Castellanos expand one solo, commissioning what became N.E. 2nd Avenue, MLP’s first major project with a local artist. The company became Castellanos’s artistic base, commissioning and presenting his devised pieces. He and Boone became close, and he helped inspire her to make fostering Miami artists and stories central to MLP’s mission.

“We both have a deeply held commitment to community,” said Boone, who calls Castellanos, now president of MLP’s board, her artistic partner. “His work is not about making something so he can go to New York or L.A. His life’s work is about being right here, right now. It’s about deepening our roots where we are.”

The ’90s were the heyday of multi-character solo shows by the likes of John Leguizamo and Danny Hoch. Castellanos was a fan—to a point. “They all represented New York really well,” he told me in 2005. “I thought, I want to represent Miami.”

N.E. 2nd, which premiered in 2002, transfixed Miami. Castellanos had an eerily chameleonic ability to embody his characters: the stiffly correct posture and indignant Creole of the Haitian jitney driver, the Cuban-Yiddish accent of a confounded Jewban (Jewish-Cuban) grandfather trying to connect with his mixed-race grandson; the survivor’s bravado and ricocheting Spanglish of the Cuban rafter selling fruit at a traffic light. We knew these people. But this city, though deeply shaped by generations of immigrants and where Latinos dominate the culture and population, had always had seen itself validated through white and/or outsider eyes, whether it was in the film Scarface or in the much-hyped arrival of Art Basel. Castellanos instead gave us a pure, pungent refraction of Miami as only somebody from here could. The piece had multiple revivals and tours. Despite his many other projects, there’s a way in which he will forever be identified with N.E. 2nd.

After Edinburgh he formed D-Projects, based at MLP, and expanded his teaching into Scratch & Burn, his first group piece. He gathered hiphop b-boys, virtuosos at breakdancing and freestyling, and spent a year and a half teaching them both traditional and non-Western forms of performance, from Chekhov to African rituals; then acted as director and collaborator to bring them together for an incandescent, movement-driven piece raging at the war in Iraq and the human drive for domination and violence.

One of those b-boys was Rudi Goblen, then 23, who, like McCraney, was transformed by working with Castellanos. He became a theatre artist and is now getting his MFA in Yale’s playwriting program (I profiled him for this magazine in 2020). Castellanos remains Goblen’s close friend and foundation. “There hasn’t been one stage I’ve been on that Teo hasn’t been there with me,” Goblen told me.

His influence hasn’t only been on the young. The transformation among the Combat Hippies, a small group of middle-aged Puerto Rican war veterans whom Castellanos began working with in 2015, under the aegis of Miami Dade College’s live arts program, may have been even more profound. He spent four years training and helping them create AMAL (Arabic for hope), a wrenching piece in text, movement, and music on the racism and trauma that comes with being from an island colonized by the U.S., then fighting its wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

The process wasn’t easy. “Getting those guys to move and perform was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Castellanos sighed to me once. Antony Torres, who now manages and raises money for the Combat Hippies, recalled thinking, “This dude wants me to dig deep into childhood and war, and now he wants me to memorize this shit and perform it onstage? I was so scared.”

Castellanos gave them courage. And something more, said Torres: “What we connected over deeply was the universality of trauma we’d all been through, including Teo—understanding that’s not all we are. We have something to say about survival and resilience and growth.”

Castellanos, too, uses theatre to process the pain in his own life, and the empathetic stress he carries from helping others deal with theirs. He came to the Combat Hippies from 2014’s Third Trinity, a multi-character solo about him and his two cousins, raised as his brothers, one a Puerto Rican nationalist and the other a Miami drug smuggler, finding redemption and mythic power in their struggle to control their destiny and find purpose. Directed by McCraney, it was Castellanos’s most personally revealing show.

Afterwards he swore he’d never do it, or another solo piece, again. “It was too personal,” he said. “It took a lot out of me emotionally.”

Buddhism has been key to balancing his emotions. He’s an ordained Zen priest who for years has started each day (except Sunday, when he sleeps in) with a pre-dawn hour of meditation. He’s a follower of the renowned Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, whose teachings on interconnectedness, and the duty to ease others’ suffering, have sustained Castellanos’s devotion to helping others and helped him deal with anger at injustice, as well as pain at his own or others’ trauma. He often refers to “no mud, no lotus,” the title of Nhat Hanh’s best-known book, which invokes the idea that good grows from bad, that they are inextricably linked.

His latest piece, F/Punk Junkies, began gestating pre-pandemic as a dive into the Black punk and New Wave music he’d loved in his 20-something nightclubbing days (dancing is still a go-to release). But over the three years it took to make, it also became a celebration of the power of its five Black and Latina women performers: three middle-aged, two non-dancers, none traditional actors. Staged at MLP’s Wynwood space in early October, it mixed surrealism with Afro-Caribbean religious myths and folklore, and the looming spirit of blues legend Robert Johnson. Castellanos, who initially meant only to direct, had a relatively small role, as a fey version of a Santeria deity who gets a beatdown when he tries to sneak into a female secret society.

One of those women was Haitian American singer-songwriter Inez Barlatier, whose father led a Haitian music group Castellanos performed with in the ’90s. She had never done theatre before, but “Teo said, ‘You can do this—I will teach you’,” she told me after a show attended by her beaming father.

Castellanos, who had knee surgery and, after two years of pandemic discipline, caught COVID just before the show, had sworn that, at 60, F/Punk would be his last live performance. Now he’s not so sure. “I must admit I had a blast,” he said.

With that project done, he was looking forward to a rare chance to travel with his wife for a week’s vacation in London. He wants to collaborate with Barlatier again, and with Shamar Watts, a charismatic Jamaican-born dancer-choreographer whom Castellanos calls “phenomenal.” He wants to further explore the potential of surrealism, “where I can make up worlds.” And through Adrienne Arsht Center, he’s directing some former WordSpeak students on a show they wrote which will tour public high schools, with Goblen as dramaturg, persevering through “hell” to get the script approved by administrators nervous over Florida’s repressive new “don’t say gay” law restricting teaching on race, gender, and sexuality.

We spoke soon after F/Punk closed over coffee in Wynwood, where the awestruck barista recognized Castellanos from an appearance at her high school. He has lived through the neighborhood’s transformations, from late-night adventures when it was a crime-plagued area, to his years at Miami Light Project’s nearby space as Wynwood became a cultural and street art haven. Now it’s filled with condos and tourists, and development has driven MLP to a new neighborhood.

Yet Castellanos remains equanimous.

“I still love my city, with all its gentrification and right-wing politics,” he said, as we settled at an outside table. “It’s hard. I guess it’s my Zen practice. If I take a stick and say I’m only fond of the left side and cut off the right end, I still have the stick. We only know happiness because we know suffering.”

Jordan Levin (she/her) is an arts writer and editor in Miami.