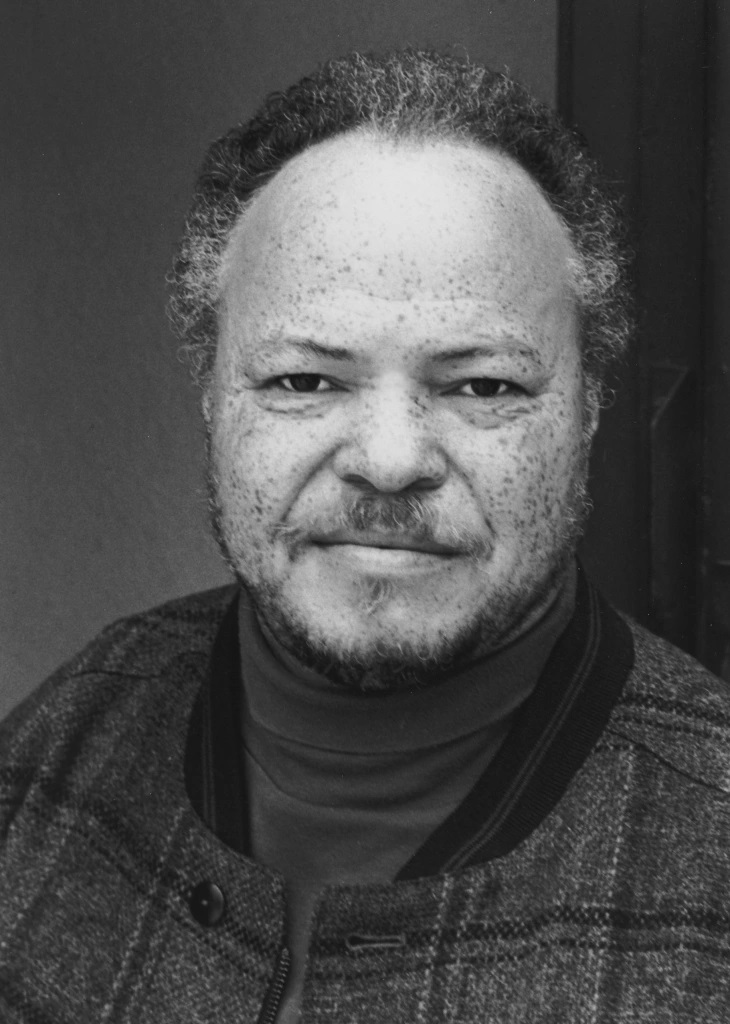

Actor, director, and educator Stephen McKinley Henderson may be best known in the theatre for his acting in many of August Wilson’s plays, but his résumé in all mediums is beyond impressive. Currently he’s reprising the role of Walter “Pops” Washington in Between Riverside and Crazy in the show’s Broadway run—a role playwright Stephen Adly Guirgis wrote expressly for him, and which he originated in an acclaimed 2014 production at the Atlantic Theater. Between Riverside and Crazy‘s opening night is Dec. 19; the last two weeks of performances (Jan. 31-Feb. 12, 2023) will be live-streamed from the Helen Hayes Theatre.

This hard-working actor, who turned 73 in August, took time out between shows to have a conversation with me.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: You were born in Kansas City, Mo. What got you involved in performing during your early days?

STEPHEN MCKINLEY HENDERSON: I started out doing talent shows in grade school and pantomiming songs, at first alone and then with a group of guys. We would work out routines to things like “Mr. Custer” and “Monster Mash” and “Charlie Brown.” I turned into a lover of poetry in junior high school, and then I got to attend a great high school, Sumner High School in Kansas City, Kans.; it had an incredible faculty and a long tradition of doing plays. The first play I did in high school was because of a teacher, a beautiful woman who was a mentor of mine for years, Gloria Terrell. She asked me to play Karl Lindner in A Raisin in the Sun because I was one of the fair-skinned Blacks in the all-Black high school. I said, “I don’t want to play the white man in A Raisin in the Sun!” She said, “Well, you can get away with this because you’re cool. You got a name on the street; the guys know you, and the other light-skinned kids in the school would take a lot of ribbing and they wouldn’t survive this.” So I did that, and then I played Helen Keller’s brother in The Miracle Worker.

Once I was a junior, they integrated the high school, but not with white students; they integrated it with white teachers. Many of the teachers who came knew about the theatrical legacy. One wanted to do Death of a Salesman, and I had the most experience in plays of anybody in the school. He tagged me to do Willy Loman. I did that, and then The Most Happy Fella, an operetta; I don’t know how I got away with that, because the music department had great singers; they just needed somebody to play the main character.

Sumner High School was one of the greatest training grounds I had. From there I went to Lincoln University, an historically Black college, the one founded by the Black cavalry in Missouri.

What was it that you gained from your family that helped you achieve professional success?

Poetry was the thing, but I used to tell my brother, who was deaf, about the parts of movies he couldn’t understand. My brother could follow the story and read the lips of the actors, but he must have seen a patchwork of the movie, so after we came back from a movie, he would ask me what was happening off-camera; I would act it out for him.

I didn’t grow up with my parents. My mother was quite young when my brother was born, and he was deaf. By the time I was born, she needed help. She gave me away to this family and then my mother had two girls. I grew up with this older couple, Mr. Benny and Ms. Irene Walton, who were a godsend to me. Ms. Irene’s father was in Black vaudeville, and Ms. Irene knew all these vaudeville routines. She would teach me those routines when I stayed home from school. She would regale me and my friends with stories of the Chitlin’ Circuit. Those stories really excited me about that kind of life, even some of the scary stories about how the performers got out of town just in time when traveling through the South.

You were educated at various places: Lincoln University, Juilliard, North Carolina School of the Arts, and Purdue. You also studied at Rose Bruford College in London and at William Esper Studio in New York City. Could you outline the chronology of your training to become an actor, and ultimately a director?

I went to Juilliard first and I got disillusioned. New York City sort of took me by storm after Kansas City. After a couple of years at Juilliard, I left and went to North Carolina School of the Arts. I was president of the student government and did some projects there. Later, I came back to give the commencement address at Juilliard and at North Carolina School of the Arts.

The summer program at the School of the Arts led to Rose Bruford, the summer studying in England. I then went to Purdue University graduate school. I was the director of the Black Theatre Workshop at the Black Culture Center and directed some shows there.

Then I joined the Rep Theatre in St. Louis, at that time the Loretto Hilton Repertory Theater, founded by the Sisters of Loretto, with money from Conrad Hilton. It is now known as the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis. That’s where I met Ron Himes, who runs the St. Louis Black Repertory Theatre.

What about William Esper?

My dear friend Harold Scott, who was a director, had headed the directing program at Rutgers for a while. He told me about Bill Esper, because Bill headed the Mason Gross School when I came to Rutgers to play Doaker in a production of The Piano Lesson. Bill asked me if I would like to study the Meisner approach and I said yes. It was an intense summer, but it was a wonderful experience. By that time, I was also teaching in Buffalo. It reenergized my teaching, because I was getting a little weary of the academic environment.

Then the next time I had that same little weariness of academe, I got to work with Lloyd Richards, because of Israel Hicks, who introduced me. Working with Lloyd was the last study I did, in my 50s, while working with August on Jitney.

You just mentioned the playwright you’re probably most associated with. How did you first come to work with August Wilson?

I had been working at the Totem Pole Playhouse in Pennsylvania, which Jean Stapleton and her husband, Bill Putch, ran. When I was driving back through Pittsburgh after doing The Boys Next Door in Pennsylvania, I met August through a serendipitous event. I got to talk with him about his plays; I was about to play Bynum in Joe Turner’s Come and Gone in Buffalo. After playing Bynum in Buffalo, and then Bono in Fences in Denver, I had a chance to get an audition for Jitney.

August kind of remembered meeting me. He said, “Oh, yeah, man, I think I remember you.” I then reminded him of a story he told me, and he said, “Oh yeah, that was you, man. I told you that was my old girlfriend coming down around the corner, and we were on that corner.” Marion McClinton cast me to play Turnbo in Jitney. We did that show for six years (1996 to 2002). We went to London and August won the Olivier Award for that production of Jitney.

I knew him until his untimely death. I feel like my whole journey prepared me to be ready for Wilson’s incredible soldiering through the American theatre. I was just glad to get on board and be a part of those, as Kenny Leon calls them, Wilson warriors.

You just mentioned several of Wilson’s plays, and I know you have been on Broadway in several: Stool Pigeon in King Hedley II, which starred Charles Brown, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Leslie Uggams, Viola Davis, and—

And Monté Russell. Monté was an actor from Pittsburgh that went all the way through to Broadway with August. He was the first young blood in Jitney.

You also did Slow Drag in the 2003 revival of Ma Rainey, and were nominated for a Tony for playing Bono in the Broadway revival of Fences with Denzel Washington and Viola Davis; you all played the same roles in the Oscar-winning film version too. How many productions of Wilson’s plays have you done?

I’ve done eight of his plays, and for several of them I’ve done two roles, but in different productions. I’ve done all but the first and the last plays in the cycle (Gem of the Ocean and Radio Golf).

In the Village Voice, Michael Feingold wrote in his obituary of Mr. Wilson that “to think of the great characters and scenes in August’s plays is to think of an epic parade of great African American actors who have seized their moment to make theater history: James Earl Jones and Mary Alice in Fences, Charles S. Dutton in Ma Rainey and The Piano Lesson, S. Epatha Merkerson confronting him in the latter, Roscoe Lee Browne sagely ironic in Two Trains Running, Stephen McKinley Henderson oozing malice in Jitney, Ruben Santiago-Hudson and Lisa Gay Hamilton glaring a skyful of weaponry at each other in Gem of the Ocean.” I should mention that Michael Feingold himself died recently. What does it mean to you to be among these great actors associated with August Wilson?

It was a very eloquent obituary; it’s worthy of literary praise. It was both a humbling and prideful experience to be mentioned in that company.

Death of a Salesman is now on Broadway with a Black Loman family. That was done before, though, including at Yale Repertory in 2009, in which you played Charley to Charles S. Dutton’s Willy Loman. What would you like to share about that experience?

It’s wonderful to see now how much Wendell Pierce’s production is being well received. When we did Death of a Salesman at Yale, there was some pushback about whether this should be happening at all. There were several Wilson actors in that production, and the critics wanted to say, “You know, August wouldn’t be happy with that casting.” What they understand today is that with the wonderful performances of Black actors all over town, and in all kinds of shows, the only reason August said he didn’t want to be lifting American classics with an all-Black cast was because they were not doing any works by Black playwrights. Now it’s a whole different field from when August did “The Ground on Which I Stand.”

Many people only know of you as an actor, but you are also a director. Your New York directorial debut was Ali! in 1992, a play by Geoffrey C. Ewing and Graydon Royce. What was it that made you feel that you also had to direct?

Well, I was asked to; that’s what happened. Geoffrey was referred to me by a couple of other people. Actually, I tried to send him to another director I knew, who had been a detective and had been a boxer, Ed Smith. Ed didn’t have faith that Ali! could be successful. It was not quite there as a play yet, but once I met Geoffrey, I knew that it was possible. Woodie King was the first person who produced us, in Louisville, Ky. It was in ragtag form, but it was successful, of course, because it was in Ali’s home. Then we cloistered away and we built the play. We did it in London at the Mermaid Theatre, which was very successful. Muhammad Ali and Henry Cooper, the great British champion, were at the show one night together. At the curtain call, Ali came on stage to congratulate Geoffrey on his performance and then called Henry Cooper to the stage, saying, “Come on, let’s fight again.” Then we did it at the Olympic Arts Festival in ’96, where Ali lit the torch.

You’ve also been a theatre educator, and you are the former chair of the Department of Theatre and Dance for the State University of New York at Buffalo. What did you gain from being a professional actor that contributed to your successful teaching career?

I tell you what it is: Harold Scott and Lloyd helped me with this. You have to find the same joy and the same fulfillment with teaching that you have with acting. You’ll know when you have achieved it—Edward Albee talks about the teaching emotion in Zoo Story. You know you’ve reached that when you are as fulfilled by seeing that light come on in students, helping them arrive at a place of enlightenment about the work. It feels like making a wonderful discovery of choice in a role. I have had students, some of whom went into law and other professions, come back and tell me that it was in my class that they realized that they could make choices, overcome obstacles, and see through to their objectives.

As I was thinking about what you have done, I started to think about you and Broadway and I realized I had not only seen you in those Wilson plays but also in Drowning Crow, A Raisin in the Sun, A Doll’s House, Part 2. You were also in Dracula, the Musical, which I did not see. How have you managed to do so many Broadway shows?

After I became chair of the department at SUNY and started working with August, when I came back I was able to get the dean to allow me to teach one semester, then take one semester off so that I could look for work. As it turned out, every time I had a semester off I got a show or a film, mainly a show, because that was when I was mainly doing theatre. I was fortunate, because I had already taught for 18 years at SUNY without a break; I had sabbaticals that allowed me to make some inroads with stage and films. If the show or film ran past that semester, I would take a leave without pay.

Stephen Adly Guirgis wrote the lead in Between Riverside and Crazy for you, and the Off-Broadway production in 2015 won you an Obie. Looking back now, what can you share about that experience?

Well, I’ll tell you: Be careful what you wish for! It has been a wonderful experience to be with Stephen, starting when he had only 15 pages and Neil Pepe at the Atlantic Theater believed in those 15 pages. Neil kept the play going; he would bring me in from Buffalo every couple of months to do a reading. I’m very grateful to Neil and the Atlantic, just as I am very grateful for James Houghton, who was the head of the Juilliard drama program and brought me back there as a teacher.

It’s quite a challenge to come back to something that you had such a wonderful experience with. Usually the revival is another production, another group of people. But we became a family, and now we’ve become the LAByrinth Theater family. I feel the same about these actors as I did about the actors who were in Jitney.

You, Elizabeth Canavan, Liza Colón-Zayas, Victor Almanzar, Michael Rispoli, and Rosal Colón were all in the premiere at the Atlantic. Now rapper/actor Common is making his Broadway debut with all of you in the new production; he plays the recently paroled son. How is having this new actor in the group changing the dynamic?

He’s bringing something that’s unique. We know him as Rashid, not as Common. Rashid is such a beautiful human being, wonderfully compassionate. His humanity is what he brings to the game, and his verve—he’s playing somebody that’s not him at all. He’s welcome in the family. We all pray before the show; he is very spiritual.

I must mention Austin Pendleton, the original director and still the director of the Broadway production.

Austin is an American theatre treasure; I first knew of him when he directed the production of Lillian Hellman’s Little Foxes where Elizabeth Taylor had her Broadway debut. He and Stephen collaborate well.

Your wife, Pamela Reed Henderson, to whom you have been married since 1978, just had surgery before the previews. How did you keep it all together during this trying time?

Because of her brother, she is recovering more and more every day. It was because of her brother that I have been able to continue to work in Between Riverside and Crazy, and our son came in too. I would not have been able to continue this production if it weren’t for my brother-in-law, Bill Reed.

What do you consider to be your greatest contribution to theatre?

The work I did with Ruben Santiago-Hudson and Indira Etwaroo of the Billie Holiday Theatre, back when we did August Wilson’s 10-play cycle at the Greene Space. Ruben Santiago-Hudson was the artistic director, and I was his associate artistic director. Chadwick Boseman, Roger Robinson, Elain Graham, among others, were part of it. We did the plays for the schools in the afternoon and then at night we did it for the public and broadcast it. The broadcasts are going to be archived and will be available at several locations across the country for study, but they will not be available commercially, as we couldn’t possibly pay the actors at that rate.

You have the last word: What would you like to share about Stephen McKinley Henderson that the world will ultimately come to know?

I just like to keep my secrets. Let them know that I’m not like Turnbo—I’m not a gossip. If you tell me something in private, I’ll hold on to it.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.