The word that kept reasserting itself as I immersed myself once again in the theatre criticism of Michael Feingold, who died on Nov. 21 at the age of 77, is “tradition.”

“Authentic tradition,” “sustained tradition,” “living tradition.” This is the value he kept rearticulating throughout his long and distinguished career—the repetition echoing the quixotic quest of an indefatigable New York theatre critic tilting against the amnesia of commercial windmills.

In a 2001 column occasioned by his 30th anniversary at The Village Voice, Feingold diagnosed the malaise of the current theatre scene by noting the absence of what had previously given it life: a vital connection to the theatrical past.

“The theatre was better when I began because its old tradition was not yet dead, and the new movement springing up to replace that tradition was brand-new and seemed inexhaustibly fresh,” he wrote. “Today the old tradition is a ghost—or worse, a zombie—and what was once new, not exactly old enough to have become a tradition itself, has instead become a habit, rigid and repetitive, its choices blindly mimicked by youngsters who don’t know that there was once meaning behind them.”

What was he holding up as an alternative? Not subservience to stage history, but a creative engagement with it, rooted in curiosity, discipline, and knowledge.

In praising Mike Nichols’ 2012 Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, which incorporated design and music elements of Elia Kazan’s original 1949 Broadway production, Feingold observed that Nichols, working from within earlier parameters, “demonstrated that it can be done: We own a tradition, and we have the right to see it constantly living and made new.”

I was, at various points in our overlapping careers at The Village Voice, Feingold’s intern, fellow critic, and editor. No matter the role, I was eternally his student. When we first met I was still a graduate student in the program that had helped shape his mind, studying with the same teachers at the Yale School of Drama’s dramaturgy and dramatic criticism program who had influenced him. Feingold was the goal to which this eccentric course of study had been designed. A modern-day Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Feingold wore the theatre’s tradition on his back, not as an ivory tower scholar but as a practitioner unleashed from the rehearsal hall into the world of intellectual journalism.

A proud Chicago-born Midwesterner who nevertheless seemed a native of the Upper West Side that he long called home, Feingold had followed Robert Brustein from Columbia University, where he did his undergraduate degree, to Yale, after Brustein had become dean of the drama school. Feingold took part in the revolution that was underway in the university’s approach to theatre training. To establish a bridge between the conservatory and professional practice, Brustein had founded the Yale Repertory Theatre. Feingold was the theatre’s first literary manager—a clear sign that the new dean was committed to an aesthetic overhaul of the drama school’s gentlemanly reputation.

A polyglot and polymath with a deep knowledge of opera and music, Feingold translated musical works by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill for the Yale Rep, including the American premiere of Happy End. A different production, featuring fellow Yale Drama School alum Meryl Streep, made it to Broadway, earning Feingold Tony nominations for his book and lyrics.

It wasn’t the last time Feingold worked on Broadway. His version of The Threepenny Opera, another Brecht-Weill masterwork, had a run at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1989, starring none other than Sting. A couple of years after I left the Voice to become the theatre critic of the Los Angeles Times, I saw Feingold’s version of Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny in the 2007 Los Angeles Opera production, directed by John Doyle and starring Audra McDonald and Patti LuPone at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

For Feingold, the practice of criticism was perfectly compatible with theatremaking. The Village Voice didn’t look askance at his moonlighting. The first time I was sent out of town to review a production was when Voice theatre editor Ross Wetzsteon assigned me to review Feingold’s translation of Max Frisch’s The Firebugs at Minneapolis’s Guthrie Theater, where Feingold had years earlier served as literary director.

I happened to love David Gordon’s production and wrote glowingly about the staging and the translation. But I later learned that Feingold was nonetheless irate about my opening paragraph. Quoting a mutual teacher of ours, Gordon Rogoff, who wrote that “Frisch doesn’t write plays, he writes dissertations,” I went on to say that The Firebugs now seems after this bracing revival to have been “the best kept secret in modern theatre.”

Feingold felt the comment to be ignorant of Frisch’s standing in the European repertoire. But as the colleague who conveyed Feingold’s displeasure shared with me, he too had never seen a production and had not heard much about the work until Feingold pitched to have his translation covered by the Voice.

As a teacher, Feingold was an unstoppable font of cultural knowledge and insight. But he was not a mentor, and he treated every underling as a future rival. The Voice was one of the rare publications that encouraged a vigorous cross-section of critical voices. But Feingold, a territorial animal in a jungle that was shrinking with alarming rapidity, established himself as the paper’s chief theatre critic, in an arrangement with management that left lingering resentments among his colleagues.

All of this took place before I arrived in 1992, but the threat of someone doing to him what he had reputedly done to others was said to be the reason he hadn’t taken a vacation from his column in years. When I became his editor in 2003, I went out of my way to assure him that he would be protected. In truth, I was protecting myself. It was obvious to me that, difficult as Feingold could be, he was unmatched as a critic.

On Mondays, when his column would arrive around 11 a.m., I found myself enlivened by the originality of his mind. I would normally have seen the shows under review the week before. Feingold’s response never failed to awaken fresh perceptions, even when I didn’t share his opinion.

What distinguished Feingold as a theatre critic? Yes, his range of reference was greater than most, encompassing not only deep expertise in numerous areas of theatre history but also a seemingly limitless fund of performances to hold up for comparison. But there was something more important that separated him from his peers.

Feingold’s greatness rested in the agility of his focus. He had the ability to take an aerial view of the work under consideration. But then, with breathtaking swiftness, he would zoom in for a closeup, discussing the production with meticulous visual detail and sensitivity to the choices of the actors and director.

He wrote with an understanding of the practical demands of theatrical production. But he was unusually mindful of the road not taken, of interpretive possibilities excluded by short-sighted artistic decision-making. Feingold wrote for insiders, in which group he included everyone with a passionate regard for the art form. He most assuredly was not writing for consumers casually wondering where to spend their entertainment dollars on a Saturday night.

His loyalty was to the theatre and its tenuous survival. Theatre institutions were ephemeral, but artists lived forever on the stage of his memory. Tradition—that word again—was for Feingold passed down by those who dedicated their lives to their art, as he had. It is a human chain, not an abstraction, and something that we must accept responsibility for sustaining.

History, in his view, wasn’t a shackle but a source of freedom. To turn your back on it is to betray not only the past but also the present and the future.

No one was better at identifying new talent. This preternatural acuity made him an invaluable dramaturg at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center’s National Playwrights Conference, where he developed an enduring bond with a then-unknown playwright named August Wilson, who was working on Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

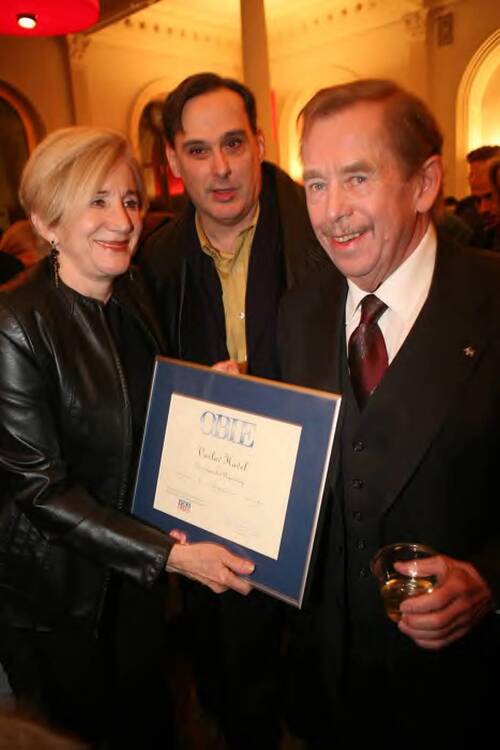

Feingold’s critical approach made him not readily transferable to other publications. The Voice was an ideal home for him not only because it provided an exceptionally well-informed readership but also because it encouraged its critics to become part of their artistic community. The Obies, honoring Off-Broadway excellence, brought Feingold for decades into close communion with leading theatremakers called to serve as fellow judges. There were a few uncomfortable moments; I recall a playwright refusing to attend the final voting meeting after Feingold had given his play a mixed review. But this was the exception. It was hard to hold a grudge against a critic of such unmistakable brilliance, unless you were an artistic director in the habit of casting unqualified TV actors in dramatic classics—a mortal sin in Feingold’s book, worthy of eternal damnation.

Kathleen Chalfant, who with the late Marian Seldes occupied the upper echelon of Feingold’s esteem, shared via email her own experience of being on the receiving end of his criticism: “Michael gave me my first grownup review in New York: ‘Kathleen Chalfant, as the ferret-faced neighbor woman, transcended the direction.’ It was perfect preparation for life in the theatre in New York, and after that Michael and I became friends. Many years later he told me that he was referring to the character, which was a perfect example of Michael’s kindness and care for his friends, even if he always told the truth as he saw it. He loved the theatre and held us all to the highest standards because otherwise, what was the point? I will miss him very, very much.”

More mainstream publications wouldn’t have tolerated the blurring of critic-artist lines as the Voice did. Still, when I became his editor, I gently moved Feingold away from reviewing the Pearl Theatre Company, where his translations of classics were regularly on the bill. He didn’t see a problem, but I knew others might. He wrote with the long view of an artist. Journalism, with its myopic concerns, couldn’t contain him. After the Voice began to falter, it was no surprise but still a profound cultural loss that he wasn’t able to find a more illustrious platform to follow his tenure there.

But there was something fundamentally scrappy about Feingold. Editors before me complained when he devoted his column to Broadway fare, passing up Off-Off-Broadway riches for high-priced midtown junk. But the theatrical fringe remained central to him. Indeed, he would lavish more intellectual care on a performance artist operating out of a hovel on the Lower East Side than on a multi-million-dollar import from the West End.

His recalcitrant and somewhat paranoiac nature made him at times an exasperating colleague. But underneath his curmudgeonly carapace was the sadness of a writer who felt he hadn’t ever been given his due. A two-time finalist for the Pulitzer in criticism, he should have won in 1992 when the board elected not to give any award in the category.

Feingold had a way of alienating even his supporters. And his lack of social graces made appearances in his writing, in dismissals that could be painfully blunt. But the chief limitation of his criticism is tied to one of his main strengths: the clarity of his unassailable conviction. For all his dialectical propensity, he didn’t often stop to ask what he might be missing. He was so defended against imagined competitors calling him out and unseating him that his self-questioning had to be kept on a tight leash. Even so, a complex humanity was always reachable via his sterling intelligence, and his robust wit had a way of offsetting the pedantic tone that would creep into his prose.

Few critics were as immune to hype. While others were touting The Producers as the musical’s second coming, Feingold recognized right away that while the charm of the show is “real and substantial,” stemming from “its ability to keep its feet firmly on the ground while its mind is wholly lost in a world of old jokes, old tunes, and old routines,” the ultimate “effect is that of a big college varsity show, on a vastly enhanced and adult professional level.”

Rereading Feingold is a cultural tonic in these days of consumerist hype and ideological grandstanding. His crankiness and hobbyhorses notwithstanding, he carried on a love affair with the theatre that lasted his entire professional life. After he left the Voice and started writing a bi-monthly column called “Thinking About Theater” for the website TheaterMania, he won a second George Jean Nathan Award for his theatre criticism.

An anthology of his theatre writing should be published, especially given the uncooperative state of the Village Voice digital archives. Feingold is an essential link in the theatre story of the last half-century, which is to say, of the last 2,500 years that prepared the way.

Charles McNulty is the theatre critic for the Los Angeles Times.