Estelle Parsons sits in her sunny living room in her Upper West Side apartment, taking an afternoon break from preparations for her annual trip to New Hampshire’s Lake Winnipesaukee, where she has spent summers since she was a girl. The sole reason for this NYC visit is her interest in promoting projects she is passionate about at the Actors Studio. If that also means talking about her life and her 70-plus year career as an actress, so be it.

“But we’re going to talk about my projects at the Studio too, I want to get the word out there—this is something people should see,” she says in that familiar, insistent, no-nonsense New England Yankee voice, which strikes certain words like gongs, that dismisses foolish talk, that cuts to core truths.

Parsons, who turned 95 a few days ago, has the energy level and work ethic of a person decades younger. Trim and active, she hikes, works out, and stays busy with acting gigs. She also has a lineup of projects into next year at the Actors Studio, an artistic home where she has been engaged for more than half a century—and been a leader there since the 1980s. To celebrate its 75th anniversary this season, the Studio plans special events in April 2023 to honor Parsons, currently the company’s co-associate artistic director in New York.

“Lee recognized early on Estelle’s ability to lead,” says Beau Gravitte, the Studio’s artistic director in New York, referring to the institution’s founding artistic director, Lee Strasberg. “It’s hard to find words to define her impact on the Studio. She is one of the foundations. She’s shown up, in person, year after year. I don’t know frankly where the Actors Studios would be without her. She’s influenced generations of actors coming out of here.”

Asked to described her work with the actors, Gravitte says that a person’s previous credits aren’t important to her; all that matters is “if you’re talented and that you work hard. But performing in front of her can be a real test of fire. She knows what she’s doing. She is exacting, and she wants you to bring it when you come onstage.”

This exacting eye extends to the organization as a whole. “She’s fearless and a fierce leader,” says executive director Deborah Dixon. “She never hesitates about picking up the phone and calling somebody. She is incredibly proactive in all things about the Studio. She is a social activist and a leader for us in diversity that goes way back way, decades and decades before #BlackLivesMatter.”

Vital Onstage

To the general public she is most known as an actor for film roles in Bonnie and Clyde (for which she won an Oscar) or Rachel, Rachel (an Oscar nomination), or perhaps for TV roles, most recently on Grace and Frankie and Roseanne (now The Conners).

But it’s the stage where she has always felt most vital and where she’s made her mark as one of theatre’s great tragic comedians. A 2004 inductee into the Theater Hall of Fame, Parsons began her stage career in Broadway musicals in the early ‘50s and continued in every decade since, most notably in plays by Edward Albee, Tennessee Williams, Dario Fo, Tony Kushner, Horton Foote, Paul Zindel, Alan Ayckbourn, and, most memorably, in Roberto Athayde’s Miss Margarida’s Way.

In later years she starred in August: Osage County on Broadway and on tour, kicked up her heels in the Gershwin musical Nice Work If You Can Get It, joined the ensemble in David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People, and received her fifth Tony nomination for The Velocity of Autumn. More recently she appeared in the Michael Friedman musical Unknown Soldier at Playwrights Horizons, in a run that was interrupted by the pandemic four days after it opened, but not before Ben Brantley could call Parsons “incomparable.”

As a director, she created the New York Shakespeare Festival Players for Joseph Papp in the 1980s, and in an effort to develop a multicultural audience they performed Shakespeare on Broadway for NYC students. She also staged many shows, including Oscar Wilde’s Salome: The Reading with Al Pacino on Broadway and on tour.

Theatre That Connects

Parsons’s recent stage projects include public presentations at the Actors Studio that grew out of sessions there. These plays and pieces, which deal with social justice, climate change, poverty, and illiteracy, and which conclude with audience talkbacks with experts in the field, are what primarily interests Parsons now. Several will be featured in the spring as part of the 75th anniversary season. She’s particularly excited to talk about one non-scripted, untitled work, built originally from an outline, that has been developed over the last few years by professional actors of color from the Studio playing men who were recently incarcerated.

“It’s not a play,” Parsons explains. “It’s more like the theatrical equivalent of jazz, where you just let these professional actors do their thing and improvise. They’ve been working on this project for a long time and they know these characters so well, so they can riff on them and make something that is theatrically dynamic and human and will leave you with something to think about.” She’s eager for the piece to reach a wider audience but as yet is not sure exactly how—perhaps at a regional theatre or with support from philanthropists interested in the issues.

Another project, also part of her “Social Justice” series, has her directing A Man of His Time, which deals with history and race across generations. The piece by Kate T. Billingsley began around 2016 as a short work at the Studio under Parsons’s eye, and is inspired by Billingsley’s own family history: One of her forebears presided as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court over the infamous 1987 Dred Scott decision, which ruled that enslaved men had no standing to sue for freedom and gave force of law to the racist notion that Black people were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The decision sparked some of the passions that led to the Civil War.

“It’s all about giving people a play that starts the conversation,” says Parsons, who also directed a 20-minute film based on the piece. Parsons hopes a full-length play will emerge and see production, with stars Sam Waterston and John Douglas Thompson reprising the roles they played in the podcast version of the play. She’s once again working the phones, her friends, and the internet to hustle interest in making that happen as well.

Yankee Spirit

Growing up in Marblehead, Mass., Parsons had an independent spirit from the beginning.

“Dad was a lawyer and my grandfather was a lawyer, and they were both out of Harvard and they had a big firm in Lynn,” she recounts.

Was a law career in the cards for her as well? It looked that way briefly, but, ironically, she says, “The only good thing about being female” at the time was that the attitude toward her career was, “People don’t care what you do. You don’t have go into the same business because your father does this or that. I’ve always done whatever I felt like doing at any given time. I never felt I had to do anything in particular. I never felt I had to have an acting career—or succeed in it. It never ever occurred to me at all.”

Indeed, she says, “I had no idea about theatre—I didn’t know what that meant. I went to theatre in Lynn for children’s plays when I was seven. It was just something I did. The woman who ran the place took a liking to me, so I did all the leading roles in the children’s plays. I played Little Bo Peep. I was good at crying. And something Frank Baum wrote called The Land of Oz, where I played a little boy. It was a lot of fun, but I didn’t expect to do that as a grown-up.”

Indeed, when she was 15, she packed herself off to boarding school, which she says she loved. “We had horses, skiing, skating. My parents didn’t want to send me but I said, ‘I’m going’—and I graduated first in my class.”

Theatre still wasn’t on her mind when she went to Connecticut College; singing was.

“I was singing all the time when I was in college. I sang and played the piano,” she recalls. “For a minute there my teacher said I should be a concert pianist, but I said, ‘No way, I have no interest in that.’ But I did play the piano and had a huge classical repertoire—which you can see I’m still working on over there.” Parsons points to sheet music on her living room piano.

“My mother wanted me to be a writer, so I was an English major in college, which lasted about two minutes,” she continues. “I was in a Shakespeare course and they started talking about Macbeth in intellectual terms, and I was so horrified I went to the dean and said, ‘I can’t be an English major. I can’t sit in a classroom and just talk about Shakespeare intellectually.’ I found that so weird, because Shakespeare was theatre to me. So I majored in political science because I thought I’d go into politics.”

Parsons did just that, following a brief time at Boston University law school, running for office in her historic hometown, just north of Boston. She became the youngest person elected to the planning board. “I thought I would go into politics before I became an actor,” she says. “I enjoyed that a lot, but thank heaven I didn’t do it.”

Early Morning Television

One day in the early ‘50s, Estelle was asked to drive a Cadillac to where her college roommate was living in New York City. That trip would change the course of her life: The roommate’s sister had married Mort Warner, then vice president at NBC, who was starting a morning television program.

“Nobody thought morning television would last,” she says. “So I went in to say hello to him and he said to send him my bio or CV—I didn’t know what that was. So I went home and typed out my whole life story and I sent it down to him and I got hired.”

For five years, Parsons ran the Today program when the show’s original host, Dave Garroway, was away for the summer. She also appeared on The Home Show with Arlene Francis in the middle of the day. She considered it her 9-to-5 day job, though, as she spent weekends singing at places like the Swan Club in Great Neck, Long Island (“‘The Lady Is a Tramp’ was my big number,” she recalls).

Despite her success on the air, she says she “never liked interviewing people. I remember I had to interview Marilyn Monroe. I didn’t know what the fuck to say to any of these people. I’m from New England, and I’m not used to asking people to talk about themselves. I really hated that.”

When she was asked to go Morocco to cover Grace Kelly’s wedding, she put her foot down; married herself, with twins, she didn’t want to be away from home for that long. Her job was taken over by someone who really wanted it: Barbara Walters.

Turning to the Stage

“One day my husband said, ‘Why don’t you go on the stage, since you’re always talking about it?’ “

In 1955 she went on as a replacement in the hit Off-Broadway production of The Threepenny Opera, which was followed by small roles in Happy Hunting and several other musicals and revues, including Julius Monk’s Upstairs at the Downstairs shows and composer Jerry Herman’s first revue.

Wait a second. I need to know: Did this change of her life’s direction really boil down to her husband saying, “Why don’t you give acting a shot?”

“That’s what I’m telling you!” she exclaims. “I’ve been busy living my life. I didn’t have any drive. And as far as acting, I just didn’t think it was something you did when you grew up.”

Was it because of her Yankee lineage, and the conservative thinking in which the theatre was not a proper place for a woman?

“That was certainly a big part of it,” she admits. “My father was never happy about it. I remember whenever I was in a scrape, he would say, ‘That’s because you’re doing these theatre things.’ “

In the ‘60s, she appeared in two new works by major playwrights of the day, Edward Albee and Tennessee Williams—but not their best works. Parsons calls both “lousy shows. I was always doing their flops, because no one else wanted to do them.” She didn’t develop a friendship with Albee, who wasn’t around for much of the production of his play Malcolm, but she did hang out with Tennessee, a.k.a. Tom, when they worked on The Seven Descents of Myrtle, directed by José Quintero (“drunk most of the time,” Parsons says). “I remember one day José didn’t show up, so we started rehearsing and Tom was telling us things about the play. In comes José and he got so mad, and said, ’Don’t ever do that with my actors.’ And Tom went toddling off to the back row.”

When Parsons was nominated for an Oscar for Bonnie and Clyde, she decided she wouldn’t attend the ceremony, as she was in a play. But the play’s producer, David Merrick—knowing the value of the high-profile event for his production—told her he was putting in her standby, so she might as well go to the Oscars. Was she glad she did?

“Yeah, it was okay,” she says. “I don’t really like experiences like that. I’m not really happy at those big events. I came back the next day to my job and to my family.” Being out in L.A., she says, “is important for people who want to have movie careers. I didn’t care whether I won or not because I didn’t care about movies.”

Even when they announced her name?

“Yeah, it was fun,” she concedes. “What’s not to like? It just was not meaningful to me. But it has been extremely meaningful in my work because then everyone says, ‘Oh, she’s the Academy Award winner,’ so it’s helpful when you’re looking for work.”

On the other hand, the work she was offered as a result wasn’t especially wide-ranging.

“You get what you won the Oscar for,” she says. “I remember once I was on a panel at the Y and this man said the strangest thing about me: He heard that if anyone needed someone to play a hysterical person they would come to me. They knew I could do it because they saw me in Bonnie and Clyde. That’s why I did Rachel, Rachel. I’m not going to repeat myself over and over again. Why would I do it? It’s not interesting to me.”

Well, there was one reason to do it: to put her kids through school. But her main focus was always the theatre. “My agents were so angry,” she says.

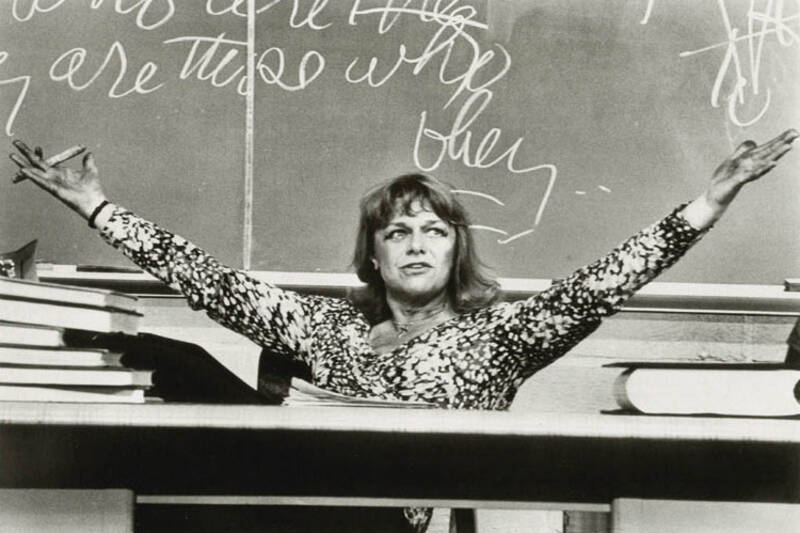

In addition to classics and new works, from Brecht to Beckett, on Broadway, Off-Broadway, and at summer and regional theatres, one of her career highlights was her tour-de-force (and sometimes improvisatory) performance in Miss Margarida’s Way, in which she played an authoritarian teacher to a classroom that comprised the theatre the audience.

“That was amazing,” she recalls. “It’s direct to the audience. You have to be a person who really wants to mix it up with audiences.”

The play was workshopped at the Public Theater, where Joe Papp initially gave the project just four weeks to develop.

“He came in after four weeks, looked at it, and said, ‘I think you need three more weeks,’ and just gave that to us. See, that was the beauty of Joe Papp. Who else in the country would say something like that?”

Few Regrets

Despite her age, Parsons says she’s eager to return to acting. She took all of last year off to be with her husband of 38 years, Peter Zimroth, as he battled a long illness; he died in November 2021. She expects to be on an episode of The Conners this coming season, and reasons, “If other jobs come along, I take them if they’re interesting. I’m ready to work.” In the meantime she has her Actors Studio projects, “so I never feel I’m out of work.”

Though she does wish she could have been part of a repertory company, she doesn’t have many regrets. “I feel I’ve had a wonderful life. That’s a movie, isn’t it?” she says with a smile. “I don’t think, ‘Oh dear, I haven’t done this, I haven’t done that. I’ll never get to do this.’ I don’t have any thoughts like that. You know why? Because all my life I’ve just done what I wanted to do at any given time.”

When asked what actors excited her, she named two: “Marlon and Kim Stanley. Kim Stanley just sparkled when she came onstage. Marlon’s another story. He was just so completely—relaxed is not the right word. It’s release. he was 100 percent there. And that doesn’t quite say it either. It was just his gift. He was just acting.”

She warms to the topic: “You can’t teach acting. Kazan wanted the Studio to be a professional workout, like a gym. That’s how it began—to make professional actors better when they work in front of a live audience, to use every part of themselves.”

One irony of the Studio is that it mainly consists of actors who work in TV and film who nevertheless practice their craft in front of a live audience, if only of their peers. You may not be able to teach acting, but this is clearly one way Estelle Parsons learned it.

“I’m more alive when I’m in front of an audience, and that’s the bottom line,” she says. “When I’m in front of an audience, every bit of me is alive, every pore is open. In real life it’s just not. What you do onstage, well, that’s it, man.”

Frank Rizzo (he/him) writes about theatre for Variety, as well as for outlets such as The New York Times, Connecticut Magazine, The Hartford Courant, Encore magazine, and other periodicals and platforms, including ShowRiz.com. Twitter: @ShowRiz.