As they say in the theatre, the show must go on. It is a motto of perseverance and priority, a signifier that no matter what happens, whether a prop breaks, your stockings tear, the set falls down, or your microphone cuts out, at the end of the day a curtain must rise and a story must be told. But what happens when this motto is taken too far? When the art becomes more important than the artists, when the production matters more than the conditions you cultivate, what recourse does anyone have?

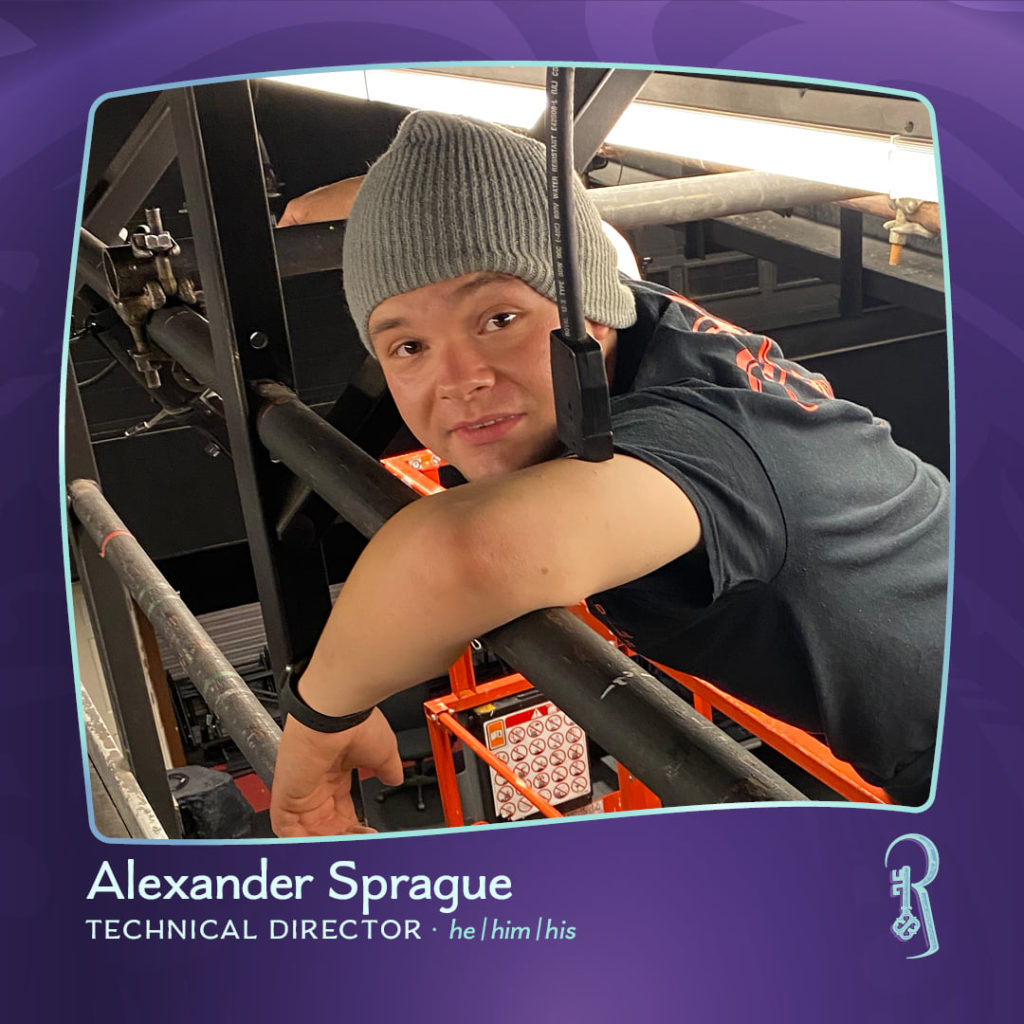

Rhode Island’s Reverie Theatre Group is redefining professionalism onstage and behind the scenes by placing emphasis on the overall theatrical process alongside performance. Its founders, artistic director Lauren Pothier, technical director Alexander Sprague, and executive director Megan Ruggiero, came together in their search for healing after exposing a culture of harm perpetuated by the artistic director at their former company. They wanted to create a place to make theatre that felt safe, fulfilling, and uplifting, sans the usual exhaustion and exploitation that is too often considered just a part of the process. For the company’s inaugural season, which continues with a New Works Festival this weekend, Reverie plans to present a selection of works exploring the theme of “Autonomy.” The road to this destination was a long and often painful one.

In spring of 2021, a member of Epic Theatre Company in Cranston, R.I., reported that they had been sexually assaulted by founding artistic director Kevin Broccoli. The theatre’s reporting policies for sexual harassment, which were written by Broccoli himself in 2017, instructed that incident reports should be directed to him. In his absence, reports could be made to the producer or general manager, who were then expected to inform the A.D. The policy offered no guidance as to the procedure in the event that the accused was the artistic director.

Following the survivor’s disclosure, the company’s then executive director, Megan Ruggiero, and general manager, Lauren Pothier, conducted a month-long investigation into the accusations, which they ultimately deemed credible. Medical records from a visit made to the survivor’s primary care physician right after the alleged assault further confirmed conditions consistent with sexual abuse, according to the Boston Globe. But as a small nonprofit theatre company without a Human Resources department or a consistently convening board of directors, Epic had no collective authority to effectively remove Broccoli from leadership.

When Pothier and Ruggiero met with Broccoli in June 2021, they outlined the allegations made against him and the findings of their investigation, and requested that he step down from his position. Broccoli refused, telling them instead that he would find his own replacement—a decision which prompted the resignations of Pothier, Ruggiero, and associate artistic director Angelique Dina.

In a statement posted to Facebook on June 23, Ruggiero elaborated on her and her colleagues’ decision to resign. “Though Kevin told us he will be remaining at Epic to accept responsibility, hold himself accountable, and swiftly try to install new leadership to carry on the company,” Ruggiero wrote, “we still felt uncomfortable remaining in our staff positions. For me, doing that would have made me feel complicit in a way and as if I were not truly taking a stand for the survivor and potentially others, which based on our investigation, I believe do exist.”

In a statement released to members of the Epic Theatre community the following morning, Broccoli wrote about his decision to stay on as artistic director, claiming that the staff resignations were his idea. He also admitted to having “absolutely made mistakes…in regards to starting inappropriate relationships with other people I had working relationships with, and, as an artistic director, I should have known better.” He continued, “Professionalism dictates that any interaction I have with someone working with the company, even while consensual, involves that person having to navigate whether or not engaging with me will be useful in some way and/or whether not engaging with me will hurt them in some way.”

Though some were persuaded by this half-apology, it wasn’t enough to contain the damage. In light of the allegations against Broccoli, Johnston’s Marian J. Mohr Memorial Library suspended him from his job as a fiction specialist, the Artists’ Exchange venue on Rolfe Square severed Epic’s residency contract, and all company productions were frozen indefinitely.

The scandal divided members of the Rhode Island theatre community. Some expressed solidarity with the victim, while others remained loyal to Broccoli. A month later, Ruggiero posted an update on Facebook, in which she called out members of the community for allowing Broccoli to “control the narrative” and failing to believe the survivor’s experience. Having reportedly “run the gamut” of controversy, losing friendships, and facing intense public scrutiny during this time, Ruggiero remained adamant that seeking accountability was the only way forward.

She wrote, “This abuser has spent one month doing nothing he claimed he would do. He has not acknowledged the truth. He has not apologized for causing somebody trauma and pain that will last a lifetime. He has not stepped down from his position at Epic and ‘put new leadership in place’ like he promised.”

In her statement, Ruggiero referred to the @broccolifrauds Instagram account, where the survivor shared details about their assault, and others from the Epic community described examples of Broccoli’s predatory behavior toward gay male company members.

Eventually the controversy died down: Epic Theatre Company dissolved, and in September 2021, Johnston police stated that they had concluded their investigation and would not file charges against Broccoli. This story could have ended here, in classic Aristotelian fashion: A man did despicable things and a company collapsed underneath him. But there would be catharsis, and even healing, yet to come.

With Reverie, the Show Can Go On

Ruggiero and Epic’s former technical director, Alexander Sprague, had already been exploring the idea of starting their own company back in 2019, but the pandemic halted their plans. Around the same time, Pothier was earning a Master’s in Public Administration from Johnson and Wales University.

“Reverie came from a group of us talking about wanting to make theatre that isn’t toxic, that doesn’t leave a bad taste in your mouth, and a place where people are paid for their time,” Pothier told me over Zoom. “We all came from different backgrounds in theatre, and we all have theatre horror stories.” She, Ruggiero, and other colleagues would regularly meet up at their favorite local teahouse and talk shop. “It’s unfortunate that [the Broccoli investigation] is what brought us together really close, but it is. We bonded over a lot of shared issues.”

Throughout the course of their investigation, Pothier and Ruggiero unearthed a culture of harm that had deep roots. “When we started talking,” Pothier said, “people were like, ‘Oh, I know what this is about.’ It was an unsaid thing in our community that no one really came forward about until now. Some people had tried to make some noise, but it never caught on. We were in a position where we could do something. It was definitely more of a situation where people knew that this had been going on to some extent.”

Ruggiero and Pothier’s findings not only exposed Broccoli as an abuser, but also revealed deep cracks in Epic’s facade, including years of lackluster management and mishandled company funds.

“All staff members were completely volunteer at Epic,” Ruggiero said. Broccoli would tell staff that Epic did not have the funds to pay everyone. Directors and stage managers were compensated, but without a formal budget process, it was difficult to keep track of payments.

“As his executive director, he finally gave me access to the bank account,” Ruggiero said. “And I started going back and investigating things, and I was like, where is this money going?”

For technical director Sprague, who also runs his own production company, working at Epic was “more of a hobby…a way to build my portfolio, which now was kind of pointless, because I just pulled everything out after the scandal.”

Working at Epic had been a big time commitment, with virtually no promise of a paycheck. “In my time at Epic,” Sprague said, “I believe I did 26 shows in a year and a half, one after the next. I did two seasons. And out of those two seasons, I made 100 bucks. There was always the promise of, ‘Oh, well, when the Patreon hits this amount of money per month, then I’ll pay out.’ Eventually I left because I just couldn’t balance Epic with my production company.”

As for Broccoli’s leadership, Sprague continued, “He wasn’t there a lot. He would pop in during tech rehearsals occasionally. There were multiple times he eviscerated both of us for over-designing something. He would disappear, show up, and then rip things to shreds. We never really felt supported by him. So for a while, it was just Megan and I running the tech process and kind of trucking along through that whole mess.”

To make matters worse, Broccoli “had a policy of no meetings. Megan and I fought to get production meetings, two per show. He was never at any of them.”

“Other people probably had very different experiences than I did,” Ruggiero said of working at Epic on the administrative side. “I never felt like it was oppressive. It just wasn’t open. There was also an element at Epic that was just like churning out work to make a profit, just constant shows. I felt like each show didn’t get its due diligence, because our team was so strapped that we were just going from one show to another and never had time to breathe, or to process the show, to fully enjoy what just happened.”

Ruggiero cited Broccoli’s “cult of personality,” which formed around the wealth of opportunities he created for the community.

“Kevin ran a company that did a lot of shows and provided a lot of roles for people to be a part of theatre in our community, myself included,” Pothier explained. “He was the person that gave me my first post-college role and really took me in after college. He had this way of collecting people and caring for them. I think it was just this magnetic thing that people were drawn to him, through no fault of our own.” That’s why, when the allegations arose, she said, “People were very wary to go against the one person who provided space for them.” And when the company collapsed, she said, “I know people were upset that the one theatre space that they had was no longer there. That was a reason why they weren’t fully supportive of us.”

Added Ruggiero, “I think that Kevin had different effects on all of the people who are now leading Reverie, and sometimes we get triggered about certain things. We’re all really understanding about that and able to talk about it with each other. He kind of used us all in different ways.”

It is unfortunate that it took intolerable conditions to foster the realization that a better way was possible.

“You should not have to push people to the brink to make art,” Ruggiero said plainly, sitting across from me at Providence, R.I.’s Schasteâ, Reverie’s unofficial birthplace, back in August. “I strongly feel it should be a fulfilling, energizing, spiritual experience—whatever spiritual means to you, it should always be uplifting. So many of us at Reverie have been involved in, not just at Epic, experiences in the area that just weren’t like that.”

Not Your Mother’s ‘Midsummer‘

One week over the summer, I made my way to New Bedford, Mass., where the newly incorporated Reverie Theatre Group was cutting its teeth on the area’s annual tradition of Shakespeare in New Bedford with an under-the-stars production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream staged on the grounds of the historic Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum.

The Shakespeare in New Bedford tradition was started by Korey Pimental, founder/co-artistic director of the Glass Horse Project and current Reverie board member, who has cerebral palsy. In an apt nod to Laura Wingfield and her hornless unicorn in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie, the Glass Horse Project was dedicated to making inclusive, accessible theatre with disabled and nondisabled artists.

While Reverie Theatre Group was forming, the Glass Horse Project was undergoing a period of transition, as Pimental headed to graduate school. Having collaborated together before, Ruggiero and the Glass Horse team decided to combine the two companies under the Reverie name, starting with Midsummer in New Bedford.

“I had a really lengthy conversation with Korey and the remaining staff members at Glass Horse about what they wanted to do,” Ruggiero said. “There was a time when we thought about staying under the Glass Horse name. That being said, because none of our leadership are disabled, we felt a little inauthentic having that name.”

They eventually landed on Reverie—a name which, Ruggiero explained, captures the sense of whimsical daydreaming, impracticality, and surrealism their artists hope to achieve through their work, while simultaneously acknowledging the ways in which artists, and especially women, are often told to “be more practical.”

In addition to carrying on the Glass Horse mission of inclusivity, accessibility, and diversity, Reverie is working to change the power dynamics at play in the theatre industry.

“Something that is really important is that all of our core leadership positions, minus our technical director, are women,” Ruggiero said. “We also have a lot of LGBT leaders. We’re really trying to empower administrators who don’t typically get those opportunities, who tend to get overlooked, particularly in this community, where it’s almost exclusively men who are leading companies.”

These practices were put into action in New Bedford, where I witnessed something truly magical: a not-your-mother’s Midsummer featuring a female-presenting Lysander, and a Deaf, male-presenting Helena, along with an assortment of fairies and folks of various genders.

This was all a part of the vision of director Taylor K. Corbett, a resident Reverie artist and former Glass Horse co-artistic director.

“Personally, and I’m sure this is a sentiment shared by quite a lot of people, I don’t think theatre is gay enough,” Corbett said. “Now it’s a little different. Kids are growing up with a lot more representation. And I think that’s due to people in my age group and a little older who didn’t have this growing up. So now it’s my job to make that happen. And Shakespeare is one of the places where we can have that representation.” Of the lovers in Midsummer, she said, “They’re hormonal teenagers. Straight kids are not the only ones with hormones that go crazy and make them do stupid things.”

Presented with the added challenge of staging an outdoor performance, the design team at Reverie was able to amp up their flower-power visual aesthetic with the use of psychedelic blacklight paint. It was a little less Dead Poets Society and a little more countercultural rave. “We’re going through hot glue like water,” Sprague joked.

“I think it was a brave decision on Taylor’s part,” Sprague said, “knowing the clientele that typically go to a Shakespeare in the Park, but they’ve been going along with it. We haven’t had any complaints about it. Nobody’s been upset. We’ve been getting all positive feedback, which is not what I expected.”

Having women-led leadership further enriched the casting process. “One of the things that I had never experienced in a casting room before was that nobody brought up anybody’s physical appearance,” Ruggiero said. “It was all about the ability and who we felt was best for the role. In some respects, gender was a little bit eliminated from the equation. It was really refreshing to have that experience, where people were talking more about the language that came through in the auditions and understanding the intent of the monologues, it wasn’t about how the people looked.”

Actress Jamie Roballo had never considered playing Lysander before being cast in Reverie’s production.

“I originally auditioned for the role of Hermia,” Roballo said, “but I was super excited when I got cast as Lysander. As a queer performer, it means so much to me to be able to tell a queer love story onstage. Lysander is a character I’ve really gotten to know and had the opportunity to make my own, and it’s been such a wonderful experience.”

Likewise, playing the lovelorn Helena had never crossed Adam Preston’s mind, let alone landing the role in his first Shakespearean production as a Deaf actor. “I remember being fascinated with Helena when studying the play and thinking that she was just the best, but I never would have dreamed that I would actually get offered an opportunity to play her as a male,” Preston said.

Preston added that the Reverie team were “probably among the first ones who have actually made me feel seen as a disabled person in theatre.” Though there were a few communication hiccups during masked rehearsals, “I was able to talk to the Reverie leaders. They heard me and they acted on it. It made me feel very seen and heard and very appreciated.”

He added that the camaraderie between the cast and crew was unmatched. “This is one of the very first shows where I’ve actually developed intimate relationships and friendships with other cast members,” Preston said. “There have been many shows I’ve been a part of where your colleagues are just there to be castmates. It’s a very transactional kind of relationship. You get along with them and you are friendly with them, but you don’t exchange numbers and make plans to hang out.” Preston said that the members of Reverie have already made plans to come cheer on his kickball team.

This level of comfort and respect seems to vindicate the emphasis Reverie’s leadership places on the kind of working environment they create. As Taylor K. Corbett told me, “Being very aware that this is something that has happened, not just in the grand echelons of Hollywood and Broadway, but also at the level of these fringe theatre groups—abuses of power can happen anywhere, and I think that’s something that we didn’t fully realize. We realize it now. We’re aware that it has to be a community and a collaboration. We’re all working together to make this, and no one can make something truly beautiful if they don’t feel safe. We want people to feel safe. And that’s from the get-go in my rehearsal room.”

Though the production didn’t have an intimacy coordinator—they plan to bring one on for their next show—the stage manager would do a check-in at the beginning of each rehearsal. Said Roballo, “She would ask not just how you were feeling physically, because obviously we were still trying to contend with the COVID-19 pandemic, but also how we were feeling mentally, how prepared we felt, and if there was anything that we needed to feel 100 percent in the space and comfortable in ourselves.”

When it came to fight calls and intimacy staging, the cast had “one-on-one conversations with Taylor and Megan about what we felt comfortable with, if we had any boundaries,” said Roballo. “Everything that came up, we would then check in with each other as actors: ‘Is this okay? Are you comfortable with me touching your arm or your hair? Is it okay if I kiss you in this scene?’ We were actually given the opportunity to say no. Just knowing that you have that ability to use your voice and say, ‘You know what? I’m not comfortable,’ makes you feel comfortable.”

After everything that happened at Epic, having a place to feel safe means a great deal to people. “I cried when we signed the paperwork to incorporate,” Sprague confessed. “I actually have our nonprofit letter hung on the wall.”

Another important piece of Reverie’s collaborative process is giving feedback, both anonymously and as a forum.

“None of us are perfect leaders,” Ruggiero said. “Something very important in theatre is to recognize that you can still learn. Our leadership team has been doing this for a very long time, in varying capacities, but we’re also learning and I’d love for the people who worked with us to be able to feel comfortable saying where we can improve.”

One key tenet in setting Reverie up for success: do less, celebrate more.

“At Epic, we had one show a month,” Ruggiero said. “With Reverie, we’re just starting out with Shakespeare in New Bedford, and then three other programs: two mainstage shows and then one New Works weekend. I think that that’s comfortable, allows some breathing room, and allows people to divide and conquer a little bit.” Even if Reverie were in a financial position to produce a jam-packed season, Ruggiero says she would never let that happen.

Next on the calendar is Reverie’s Dream Makers: New Works Festival, slated for Nov. 27 and 28 at Kingston’s Courthouse Center for the Arts, followed by Frank Wedekind’s The Awakening of Spring in February and Lysistrata in April.

Along with a pared-down calendar, the company is being conscientious about its funding. The Shakespeare in New Bedford program is funded through a series of state and local grants, as well as support from the Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum. Going forward, Reverie plans to fundraise and apply for grants so that all the artists involved with their productions will be compensated fairly.

For the folks in Rhode Island and elsewhere who are reckoning with the effects of trauma in the theatre, let Reverie be a case study, not in how to be perfect, but how to begin the healing process. The COVID pandemic has forced us to see the limits of our industry’s expectations of endurance. We have lost and we have suffered, but whether we’ve learned anything remains to be seen. For now, the show can go on, and that’s something to celebrate.

Alexandra Pierson (she/her) is associate editor of American Theatre. apierson@tcg.org