George Faison’s extraordinary talent has taken many forms: dancer, choreographer, actor, director, composer, producer, essayist, playwright, writer. Faison’s multifaceted career has rightly earned him admiration as a renaissance man. The numerous honors, prizes, acclaims, and accolades on his shelf are for the many works he’s created, staged, and choreographed, including Suite Otis and Slaves, and the Broadway shows he worked on, including Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope and The Wiz. In 1975, that last credit made him the first Black person to win a choreography Tony. He also worked as a choreographer for such legendary Black musical artists as Aretha Franklin, Roberta Flack, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick, Ashford & Simpson, and Earth, Wind & Fire.

Now 76, Faison took time over the summer to sit down and talk to me about his various careers and collaborations.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: Mr. Faison, there is no way I can cover your entire career, as you have done so much. But let’s start with your early years. You were born in Washington, D.C., and attended Dunbar High School. What can you share about your early upbringing and high school days?

GEORGE FAISON: My Washington upbringing—I had a father and a mother, and I lived with them. I know that this is important, only because when that happens, when you are raised by both parents, it has a bearing as you meet other people. It gives you an understanding what it is also to grow up without that support. I lived in the ghetto—1521 3rd Street was considered the ghetto, but it was on the road to Howard University. We were always involved with Howard. I don’t know if they deliberately had connections with the community, but they were part of what was going on—it was like a lightning rod. Growing up, I went to Howard first to have some dance classes when I was still in high school. That program was started by Maryrose Reeves Allen, and that was the beginning of dance at Howard. It was so long ago that I was in on a lot of firsts.

Did you start dancing in high school or before?

When I was 15, I was dancing in classes at Jones-Haywood Dance School with Chita Rivera, with Louis Johnson. Then I got to study liturgical dance with a group that rehearsed at the St. Mark’s Church. Mary Craighill did liturgical dance, and I became a dancer with her. Later, with other white modern dance companies, I learned some of the older modern dance techniques from Doris Humphrey and Ted Shawn. The first dance I did of theirs was The Shakers, a religious dance—I was a Black shaker shaking with the Shakers. I was a sponge, just taking up everything.

You also attended Howard University for a short period. I know you studied with Owen Dodson. Who else did you study with at Howard?

Ted Shine was there as well. I didn’t last long. My mother worked for a dentist who taught at Howard; she thought that was the road I should take. Then one magical evening a friend invited me to Cramton Auditorium. The Kiss Me, Kate production with the American Light Opera Company was the first production on that campus, in that auditorium. It was brand new. It was the next time I was there that meant so much to me—it was when I saw Alvin Ailey; when the curtain rose on that, I was home.

You say you were there for just a short time. Did you gain anything else that you felt aided you in what you were moving toward?

You were always learning something, or you were always introduced to something, to art that you could actually see—the students who were in fine arts and that painted and made sculpture, and so forth. I was part of that. And I did productions on campus. I did Jamaica with Louis Johnson. Actually, after meeting him, he became my mentor. That was my connection. Then Louis called me one day and said that they were having an audition for Arthur Mitchell; he was going to Africa, to President Senghor’s the First World Festival of Black Arts in Senegal, and I was introduced to the great classics of Black modern dance.

They did not end up going to Senegal after all, and that dashed my hopes about going to Africa with this incredible bunch of dancers. Here I am, skinny old me, so I got with Black dancers and joined a company called HARYOU (Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited) that was the anti-poverty program they had in Harlem. HARYOU was what it was: a bunch of thieves, crooks; they stole the money and worked us to death. While we were really learning to learn it—the choreography, the technique—we got introduced to Thelma Hill, who had danced with Ailey. Thelma was a prominent dancer from the Negro Ballet back in the 1930s, when all of them first went to Europe.

In 1966, you were chosen to become a dance partner with Lauren Bacall in a special on television, Stage 67. What is the story there?

This is how I got that job: A guy was late. I went to the audition, and I was probably going to be cut, but I was the last of the ones they had. And they were waiting for him. God set the clock turning and I was chosen. He came into the room, but I had already been given the job. Oh, the luck, and all the good will, and all of the wonderfulness that has happened to me has happened like that. All I could do was to prepare for it and get ready for that next moment.

You were a member of and danced with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater from 1966 through 1970. Can you tell me about that time?

I saw the world. He introduced me to all of that. Alvin was extremely intelligent to start with, being an artist, a choreographer. I think I got some of my techniques from that. Clive Barnes, in The New York Times, said I am a disciple of Ailey’s and probably the one closest to his legacy. But they didn’t tell me that; I went on about my business. I didn’t read the reviews and just kept moving on.

I know you had some good experiences with the Ailey company. Was it all good, though? Were there any bad times?

When he couldn’t pay; when he didn’t have money and he stored the costumes in my house. It was like that. He was going through the question of whether to have a company or not. Those were really the hard times. We saw him through that until he was taken on and toured. Down in the South we got put out of restaurants.

We were on the road in 1968, at Lincoln College, when they announced during the intermission that Dr. King had been shot. We ended that program with Revelations, and it was really, really tough. Then all the hurt and pain erupted after that. I went to Europe again, and while I was standing in the Piazza del Duomo in Milan, I opened the newspaper and the middle page had “Detroit on Fire.” I can’t tell you what went through my body, seeing that. It left an indelible impression. I am truly one of the children of the Civil Rights Movement, and I still am.

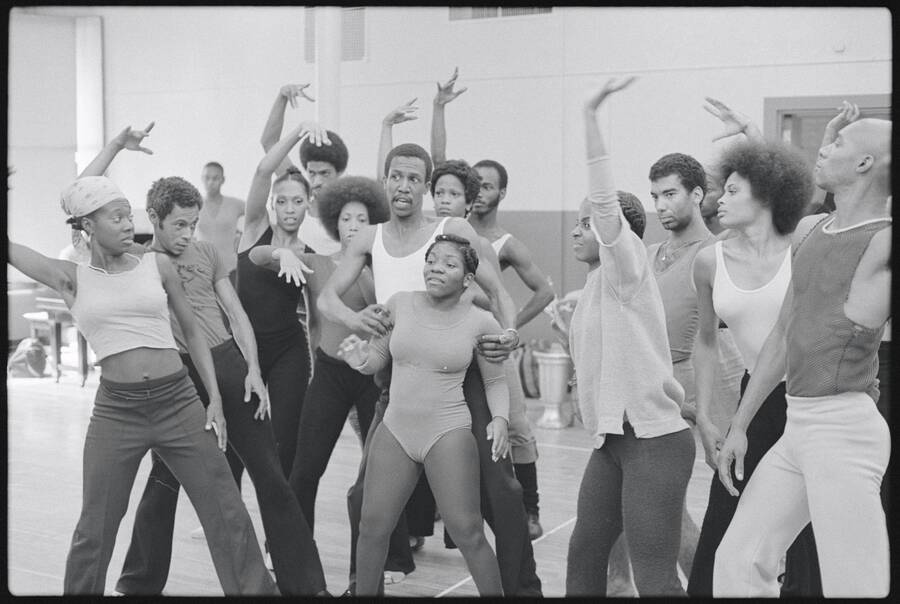

In 1971, you started the George Faison Universal Dance Experience. What motivated you to take that step?

I had my own message. I wasn’t going to fight Alvin. That was his company. I was not going to cause dissension to rise. The people who stayed with Alvin and loved him—they made it hard for him. Those were contentious relationships, until they got more money or he placated their needs. They didn’t create. They just stayed there. I was not going to stay with Alvin Ailey and complain. The last day I saw him I told him that I wanted to do Gazelle, and his reply was, “I’ll pencil it in.” I was outraged and cried all the way home.

Did Alvin feel that you were trying to compete with him or take something away from him?

No, we didn’t talk about that, and I didn’t feel like that. After all of the time of calling me George, he said, “Okay, Faison, what are you going to do?” He had never called me that. He probably came back from that when he saw what I was doing. I did my company. I did Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope. He sees one of his proteges, and then he hears that I won the Tony. And we were friends all that time. He later asked me to add Gazelle in his company in 1977, Suite Otis, and so forth. They paid me. And in the meantime, I was staging Earth, Wind & Fire, Ashford & Simpson, Brothers Johnson, The Emotions, Gladys Knight & the Pips, The Supremes. All you had to do was relax and let it take its course. I have an imagination. I could dream. You can’t ever, ever lose that.

What can you share about Poppy?

That was a drug ballet. It was in vogue to do a ballet about drugs. The choreographer who led that was Eleo Pomare. He was the rebel. He did jazz, Coltrane and stuff like that. He did Narcissus Rising, where he danced in a dance belt, and chains that dripped down, and motorcycle clothes, and a motorcycle helmet, very sadistic. We knew each other. We were all on each other’s programs. That’s how it was. You know, half of the people who are doing solo programs, they shouldn’t be doing solo programs. Do one good dance. Get on a program.

Your name is associated with many dance classics, including Suite Otis, from 1971. What can you share about that piece?

That Black people make romantic love, and Otis Redding said the rest. I stayed away from “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay,” because I was tragically hurt when I saw those pictures of them taking him out of the water.

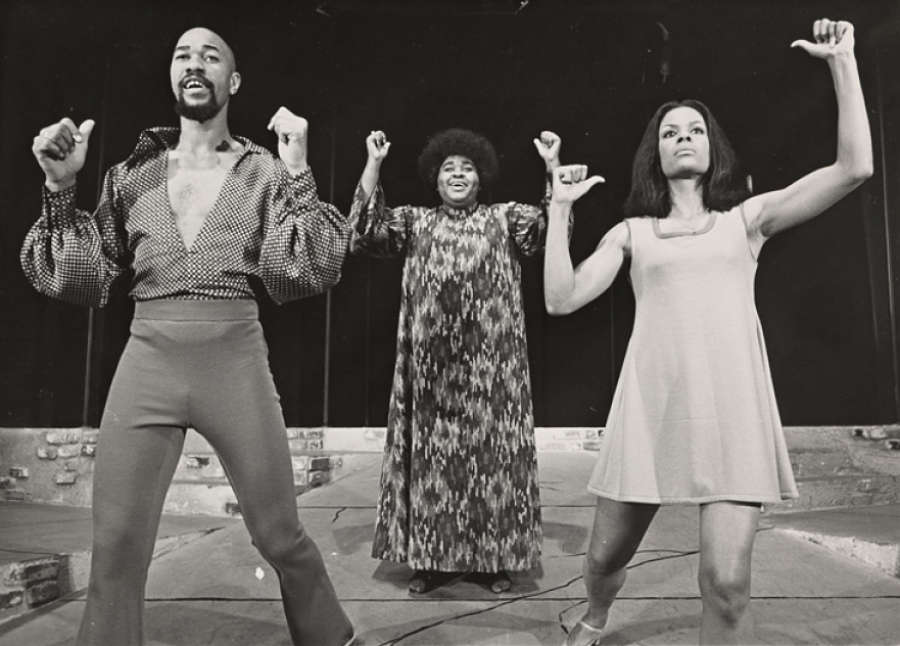

Your Broadway debut as a choreographer was Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope with Vinnette Carroll and Micki Grant. How did that come about?

Well, somebody called me—I think it was Hope Clarke—and she said, “We need a choreographer. We need you to come down here and meet Vinnette and do the dances for this show. They fired Talley Beatty.” I was aghast. Talley was one of my mentors. He choreographed the classics as far as Black jazz and modern dance are concerned. I was overwhelmed with that. It was crazy.

What about working with Micki Grant?

Micki Grant was a very, very talented composer of music. She is not unlike Charlie Smalls, and what he did with words and music. He is one of the few Black composers who ever graced Broadway, and we don’t hear anything about him. They put up all these fake productions of The Wiz. It is just horrible. Every one of them is dreadful. Diana’s too.

Micki Grant was a very talented composer. She found her own voice. She wrote the lyrics for and performed, “It Takes a Whole Lot of Human Feeling”—and it does, to be a human being. Those are things that haunt us and come back to remind us. That was part of the protest. Art is supposed to reflect the people, and she did that. She reflected who we were and the struggle that we were having.

As choreographer of The Wiz, you were the first Black choreographer to win a Tony in that category, in 1975, as well as the Drama Critics Circle Award. You were only 29 years old at the time. What did these awards do for your career?

It all meant freedom. I got my piece of freedom paper with the Tony Award. It is the pinnacle of my climb to the kind of recognition you can attain when you do something that is totally original, and I was able to do that in The Wiz. So I could call on all the magic I had from my dance company, from the concerts, from Alvin’s company, from everything I learned from people, that I learned from Fred Astaire, from the movies. Everything I had learned and seen, that I had been educated with. I could put in that; I could use my life; I could use people in my life. There’s a number, “Y’All Got It.” That was James Brown right in front of your face. I could do all of that.

In 1976, you worked with Leonard Bernstein on the musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. What can you share about that?

I was called in there at the last minute. You had two rich white guys, Leonard Bernstein and Alan Jay Lerner, trying to tell an African American story. They had very good intentions. What more can I ask for? But the thing was in a shambles. I have been involved in a couple of musicals that tried to include the Civil War, but they ended up fighting it all over. White boys are like that; they didn’t get it until they started tearing down these statues and becoming the Oakwood boys picking up robes, and burning flames again. That was the story of the White House. We had dazzling performances from the English actors, like Patricia Routledge—to watch her work! But the show wasn’t sharp enough. It wasn’t savvy enough. We were trying to face a new day. Yes, they wrote songs of freedom that were stirring and so forth, but we know the outcome of the Civil War.

Again, I started my career wanting people to know my story. What I put onstage, sometimes it was too real for them.

Apollo, Just like Magic, was a major Off-Broadway success in 1981. What would you like to share about that?

I could actually do that today. It was about the reopening of the Apollo Theater, and these fictitious guests there, but it invoked the spirit of it. We were looking down on the Apollo, hoping for a great opening, and we are in turmoil on the streets. I got to be on the streets. I got to be reflecting the people. We were always shortchanged by producers because they didn’t have money, and they couldn’t produce, and they made mistakes. We had to suffer all of those, the changes that arose during that as well.

You have worked with many well-known artists, and I would like to know about your experiences with many of them. I’ll start with Jennifer Holiday, with whom you worked on 1985’s Sing, Mahalia, Sing, about the life of Mahalia Jackson?

Jennifer was made for it, but it was difficult; she was difficult. She even auditioned for the movie of A Color Purple and took off one Sunday to her own detriment, because the understudy was Queen Esther Marrow, and she went on and brought the house down, just like Hinton Battle brought the house down when he did the Scarecrow in The Wiz, when Stu Gilliam decided he was going to take a day off the very day that 20th Century Fox came to see the show.

We talked about Louis Johnson. What more would you like to share about him?

Louis Johnson was one of the premiere dancers of our era. He danced in Damn Yankees. He was like Jackie Robinson: When we were not dancing and could not get work, there was Louis representing. When we were nowhere, nowhere, nothing—he was there.

At one point, Miles Davis made all of his music available to you. What is the story behind this?

That’s crazy. He invited well-known choreographers, Michael Peters and all of my contemporaries, to his house and gave us a lecture about his music. Then at the end of that, he asked us individually what we felt about his music. All the other people were star-struck, but I had heard the music and had been around a great number of musicians. I told him stories of what I felt about each one of his compositions. At the end of the meeting, he gave me all the tapes, every one of them. And I used one in one of my first ballets, Poppy.

You have also been the choreographer for many musical groups and entertainers, some of which you mentioned before but also including Dionne Warwick, Patti LaBelle, Aretha Franklin Stevie Wonder, Natalie Cole. Who did you enjoy working with most, and why?

Stevie is definitely one. Ashford & Simpson have a very special place. But the queen of all of that probably was Maya Angelou, who was a friend of mine for a long time. We drank together, we cursed together, and then I apologized. We partied. We ate great food, and she told great stories.

What would you like to share about Tad Schnugg, with whom you cofounded the Faison Firehouse Theater?

Well, he was the love of my life, and I’m so glad. You should never go through life without a partner. Do not go through this life without sharing it with another human being.

What advice can you offer to any artist who wishes to follow in George Faison’s footsteps?

Just have courage to open the door. Even though you don’t know what door you are knocking on, open the door and go through.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.