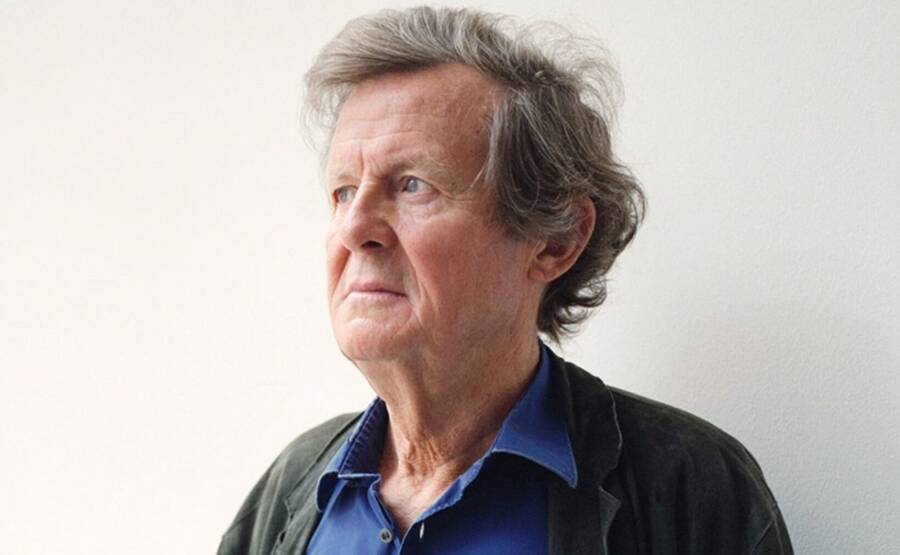

“Is that Barry Diller Island?” David Hare asked me a few weeks ago. The seasoned British playwright was referring to my Zoom background—I like to vary it up when I do these now obligatory online interviews, and a picture of Little Island, the somewhat whimsical, Diller-spearheaded concrete-and-foliage attraction in Hudson River Park, is one of my go-to slides. I hadn’t quite intended it, but this seemed an remarkably fitting kick-off for the subject of our conversation: Robert Moses, the larger-than-life planning tsar who transformed the face of mid-century New York City and surrounding areas with miles of expressways and parks, and who is the lead character of Straight Line Crazy, Hare’s new play, now at the Shed in Hudson Yards through Dec. 18, directed by Nicholas Hytner and starring Ralph Fiennes as Moses.

I was quite curious to find out why Hare—who has written several plays about British institutions (from Pravda to Racing Demon to The Permanent Way), as well more intimate dramas (Skylight is typical, and a personal favorite), but precious few about American life (Stuff Happens, his sharp play about the lead-up to the Gulf War, is a notable exception)—wanted to write a play about Moses, a city planner best known to Americans, to the extent he’s known at all, as the urban villain of Robert Caro’s 1974 book The Power Broker, and who is certainly quite unknown to Brits, for whom the play nevertheless opened to strong reviews earlier this year. It would be a bit like Aaron Sorkin writing a play about Sir Patrick Abercrombie. But apart from an invented Irishwoman on Moses’s staff, played by Siobhán Cullen, Hare has written a convincingly all-American drama, even if its preoccupations are in line with the subjects of much of Hare’s career, as I found when I spoke to him.

We happened to be speaking hours after Liz Truss stepped down as the U.K. Prime Minister, while Hare was in New York for Straight Line Crazy rehearsals and previews. Following is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: It’s an interesting day to be speaking to you. Is this interview a break from your catching up with the news?

DAVID HARE: I was asked to write 3,000 words today on the subject, but it’s all happening too fast and I’m too far away. I haven’t got time anyway, with previews, to coordinate my thoughts. So I’ve turned down that gig.

It seems like a lot of heads-of-state history is happening across the pond lately.

I did do a piece about the Queen. The Guardian rang me about nine months before she died and said, “You know, we’re a republican newspaper, so we haven’t got an article for when the Queen dies; would you like the job?” I said no, and then an hour later, I rang back and said, “Actually, I would, because in some way her history is my history.” So I really enjoyed writing it, and I seemed to get away with a few criticisms of the monarchy which I did not get shot for. Considering how Stalinist the press became for those 10 days after she died, I was very lucky to get away with some modest criticisms of her reign.

So, enough British stuff for a moment. I was looking through your long list of plays and couldn’t find many on American themes, or featuring many Americans. There was Stuff Happens and then The Vertical Hour, about 16 years ago. Have there been any since?

No. There was an American theatre critic, John Lahr, who used to write in The New Yorker, and he wrote a sentence where he said that there was no British play in which Americans were not represented as vulgar and stupid, and that there was no sympathetic representation of an American on the British stage. I took this extremely personally, and I was very insulted by it. Because by then I’d written The Vertical Hour and Stuff Happens; you know, I had represented Americans on the British stage, and I’ve represented them extremely sympathetically. So he was talking through his hat.

What drew you to this subject, then? Not just a chance to prove Lahr wrong, surely.

When Nick Hytner left the National Theatre about six years ago, he became convinced he should have presented a play about Robert Moses. And when he had a theatre of his own, the Bridge, a new commercial theatre that he runs right by Tower Bridge, a very beautiful spot, he asked me if I’d read Robert Caro’s book; I had 10 years previously, and he asked me to reread it. When I did, I felt that, great as Caro was as the pioneer and the incredible master of this subject, nevertheless it was possible to take a different view of Moses. That’s what made me want to write it—the feeling that the conversation that various writers have had with Caro since then, and the other things that had been written, freed the subject up. You know, Caro’s book was so monumental, so original, so brilliant, that I think for a while it killed the subject stone dead. But I think now we can see Moses differently. And I see him very differently from the way Caro did.

I think I know what you mean, but could you elaborate more on how you see him differently? I feel like there’s a lot of Caro’s version of Moses in your play, even as you allow him to make more of a case for himself than Caro does.

Well, Caro’s book is all in the title: the power broker. He had this extraordinarily original thesis, which is that Moses created a fourth arm of government, and he did that with tolls—by having people throw 25 cents into the bridge toll or the road toll or the tunnel toll, and the money went to Moses, and so Moses was able to create a center of power which was independent of democratic control. That’s really what Caro is writing about, and he’s writing, therefore, about somebody who becomes corrupted by power, and who becomes more interested in power than in the work. I don’t see him that way. I see him as someone who was originally idealistic, and had an ideal, which was to open up Long Island to the working class, to the tenements, to the people who lived in appalling conditions in New York City, and to give them a kind of rural paradise. And he did that. The means by which he did it was the road; he believed in the motorcar as the instrument of his idealism. When attitudes to that changed, and it began to be clear as early as the 1950s the damage the motorcar was doing to social structures, he could not adapt his dream, in my view; his dream was too rigid, and he was also so frosty. He had taken so much criticism that he’d become incredibly touchy. And he just believed that because he had once been right, he was always going to be right. He was right about Jones Beach, and he was right about Long Island. Everything he did there is very, very beautiful, almost Soviet. But 40 years later, he had failed to adapt his dream.

For me, this play is universal. It’s not about urban planning. I’m happy to say it’s a very popular play with urban planners, who never imagined there would be a play about them. But to me it’s a play about how we all have dreams in our youth and that it is very hard to adapt to reality as time goes by. He’s a tragic figure.

I do see that arc in your play, but he’s still quite a tough character. Even when he’s describing his idealistic vision of the civil service, it’s about flushing out the dead weight, minimizing inefficiency. So there’s always a bit of an edge to his ideas. The one about building parks for the people is relatively pure, but even there, he seems to be one of those folks who talks a lot about “the people” but doesn’t like actual people very much.

That’s absolutely right. He did have difficulty with people, and that’s why the only time he ran for elected office, it was a disaster. He decided to achieve what he wanted without the difficulties of submitting himself to the people. I mean, the other thing the play does is recover the figure of Al Smith, who is not known even to a lot of New Yorkers. LaGuardia is the man who is sort of represented as the author of modern New York, but Al Smith was an extraordinary governor—a fantastic, genuine democratic figure. And he stood for election all the time. His partnership with Moses was an extraordinary mixture of two very different men, one extremely educated, high-falutin’—you know, he wrote with references to Sophocles, Aristotle, Ben Jonson—and then Al Smith, the ultimate man of the streets and a popular politician.

I saw a bit of Nixon in your Moses—as when he seems to fixate on how well liked the Catholic politician is, in contrast to himself.

That’s right, that’s deliberate.

The other person I thought of was Dick Cheney, who spent so long behind the scenes, learning where all the levers of power were in the White House, or Mitch McConnell, who’s done the same in the Senate.

Yeah, I don’t personally see Moses that way. I don’t think power is what Moses was about. What Moses is about is the imposition of a dream, the imposition of an idea of how society might be, and of how the landscape might be structured to facilitate that. That’s why the lives of the many are what he’s interested in. That’s why he’s so opposed to the preservation movement, which he regards is completely ridiculous. He regards it as what we call NIMBY in England. So when Jane Jacobs and Shirley Hayes and the other mid-century visionaries appear, who want to start what we now know as the preservation movement, he’s viscerally opposed to that, because as far as he’s concerned, that’s just well off people holding on to nice things, not wanting to share the pleasures of privilege with everybody. So it’s a complicated thing. And you must remember that the movement to preserve Washington Square was multi-political. Libertarians and Goldwater Republicans were part of that movement, because they too were opposed to public planning; they didn’t think government knew best. They wanted, like Jane Jacobs, to create from underneath. That may be a right-wing idea or it may be a left-wing idea, but that was a coalition of interest he finally couldn’t deal with.

And your play has Jane Jacobs admit at the end that saving the Greenwich Village she knew meant that it was also in a sense destroyed.

I mean, the catastrophe of New York—when I first came to the city in 1965, everybody lived cheek by jowl, and you would go from block to block and the poor would be there, and then the rich would be there, and then the middle would be there. That’s totally gone, because now you need so much money to live in Manhattan. That is one of the unfortunate effects, and, as Jane Jacobs says, she’s not sure if that’s her fault or Moses’s that it happened.

You can’t argue that the great crime of Moses, without any question, was the Cross Bronx Expressway. That was a racist enterprise. As James Baldwin said: “When I hear the words ‘urban renewal,’ they mean ‘Negro removal.’” The tragedy of New York was that the middle class could organize successfully to save Washington Square, but the Puerto Ricans and African Americans could not organize successfully in the Bronx—not through any failing of their own, but because nobody was willing to listen to them. If you look at the three times Moses is most significantly defeated, it was by middle-class interest groups. He is defeated in Washington Square; he’s defeated when he tries to turn a playground in Central Park into a parking lot, where the rich women of the East Side coalesce against him. And then he’s defeated by Joe Papp when he wants to build the Delacorte. Joe fights on behalf of culture, middle-class culture—Joe would resent my saying that—

I mean, he came from the working class, but I know what you mean.

Right, nevertheless, he’s putting on Shakespeare, so Joe wins. So Moses is defeated three times, always by middle-class groups.

You’ve written a number of plays about how systems work, or about how people work within and against systems, as with your series of plays about British institutions. Do you see them that way? Do you consciously set out to write about systems, or do you start with the human stories?

I suppose I have a view about human history. I don’t know what people are talking about when they talk about the universal, really. I don’t like what I call bell jar plays—plays in rooms, plays where people are treated as if everything is universal. I like specific plays in which you can feel the wind of history blowing across the stage. I don’t think our lives are the same as the lives of the Chinese peasants; if I’m going to write about Chinese peasants, I want to define the society they’re living in at the time they’re living in it, to make you feel the particular conditions which are giving them the feelings that they have. In that sense I’m not a Marxist. I do believe that historical context, social context, is everything; and in the theatre, it’s kind of necessary. I’m bored by Beckett, because he’s seeming to imply that everybody’s the same and the human condition is we’re born, we die.

What I’m interested in is the line between necessary and unnecessary suffering. That’s what I write about. Clearly, our lives are tragic, we have to suffer. But how much do we have to suffer? And why do we have to suffer? What do we have to suffer? And how can we change the things that we’re suffering that we don’t need to suffer? That is what that is what all the plays I write are basically about. Can we change the system? In what ways can the system be improved so that there is less suffering? That’s not all I’m interested in, but it’s always about people. It always has to be about people, because it has to be about the relief of the suffering. You know, the wonderful thing in Caro’s book is when he goes and just takes one mile in the Bronx, and examines exactly who suffered and why they suffered and what has now happened to them. That is why that book is given to people who want to study journalism at Columbia. They are sent that book before they arrived. Reporting means getting close to the lives of people who are suffering because of the decisions that are made at the top.

It’s funny you mention journalism, because I thought of Stuff Happens as a quasi-journalistic effort—an attempt to stage a first draft of history.

I like reporting. I did Behind the Beautiful Forevers, an adaptation of Katherine Boo’s book, which is a genius piece of reporting, saying, “You think you know what a slum is like? You know nothing about living in a slum. Let me, who spent three years in a particular slum, Annawadi, tell you what that slum is like.” That, I think, is a fantastic rmission. But I don’t think it’s enough. I think whatever you write about in the theatre has also got to have some metaphorical power. In other words, I don’t like journalism on the stage. I like learning about what I don’t know, in the interests of the play then being understood metaphorically. The classic response was a friend who came to The Permanent Way, which I thought was a play about railway crashes and the privatization of the British railway system, and my friend from New York was in floods of tears at the end. And I said a stupid, glib thing: “Oh, I didn’t know you cared so much about the British railway system.” And he said, “I didn’t see it as that, I saw it as a play about AIDS in the 1980s in New York, about my friends who died when they did not need to die because the system wouldn’t move to accommodate the catastrophes that were happening, and wouldn’t recognize the catastrophes that were happening.” He was in pieces.

I want to ask you about this well-worn term, the “state of the nation” play, a genre English playwrights are supposed to be known for, you included. Do you accept the label?

You know, I got landed with that, but all playwrights get landed with something. I don’t think Harold Pinter was very happy to be called theatre of the absurd. A journalistic tag always goes on what you do, and it’s very frustrating in the sense that, you know, when I write about all sorts of other things that are also interesting to me, I get, “Oh, you also do that?” But you know, I’m lumbered with it. What can I do?

I mean, if you’re saying to me that there is a broad tradition that you might say starts around about Heartbreak House with Bernard Shaw and with Harley Granville-Barker—socially realistic, but also epic. Yeah, I wanted to make the stage as free as cinema; I wanted to give it the freedom of the cinema, and also the social specificity of the cinema. My generation were brought up on cinema, and theatre was second best to us. I want plays to move freely and to make interesting juxtapositions. You know, Howard Brenton and I used to joke about, can we go from a mountaintop to a factory, from a factory to the Antarctic, from the Antarctic to a ship? By making interesting collisions, interesting things happen.

And so yes, that tradition of British epic that is also humanist, is based on people—yeah, that exists. A very rich and wonderful tradition it is too. The most successful players of the 21st century are all bang in that tradition. The Lehman Trilogy could have been presented by Joint Stock in the 1970s. Jerusalem is a completely classic Royal Court play of a kind that could have been written in the 1960s. So those those are very live traditions in Britain, and very rich traditions.

I feel like American playwrights are often trying to gesture toward that tradition, whether it’s Tony Kushner or The Civilians. I think you could also argue that Black playwrights have been writing state-of-the-nation plays for decades, from Lorraine Hansberry to Lynn Nottage.

My impression is that the American theatre is changing very fast. You know, Joe Papp used to keep saying to me, “I’m only doing your plays at the Public because there aren’t any American playwrights doing what you’re doing.” He used to be very rude to me and Caryl Churchill, and say, “Don’t think I’m doing these plays because I like them; I don’t like resorting to British playwrights, because that’s not producing to me.” Producing to him would be going into the African American community and finding African American writers. He said, “I’m only putting your plays on to show American writers what I think they should be doing.” That was his mission. My instinct is that things have changed since then, but I don’t know the American theatre well enough to be able to say that authoritatively.

You mean you think more playwrights are writing the kinds of plays that Joe would have produced back in the day?

That’s my feeling. And Joe was the visionary; he was way ahead of its time.

The other throughline of your work is that you’re very good at portraying the seductive vitality of rather bad people. You mentioned Shaw earlier, and I think of one of his signatures as giving the characters he probably disapproved of the most some of the best lines.

What’s the point of being a playwright if it’s not to invent people, and to articulate people who have completely different life experiences from your own? I’ve always said that the whole thing about my doing women so often, and being known as a playwright who wrote parts for women, was that I loved the leap of imagination. I didn’t want to write about being me. I’m not remotely interested. But I’m very, very interested in other people. That is what a playwright does, and why would you not relish the prospect of presenting people who are as unlike you as possible? So yeah, it may release in me what Philip Roth would call your demons. You know, he always said to me, “I love your demons, David,” particularly the way, in Pravda, Howard Brenton and I portrayed an early version of Rupert Murdoch. He just said, “You can’t liberate yourself as a writer until you release all the ugliness inside yourself, as well as all the beauty inside yourself.”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org