Happy Halloween! As American Theatre has done since 2016, we’ve collected another batch of haunted theatre tales from across North America. We hope this year’s anthology of ghost stories makes for a thrilling addition to your collection of holiday treats.

Dime Drops, a Blue Lady, and a Mystery Bathroom

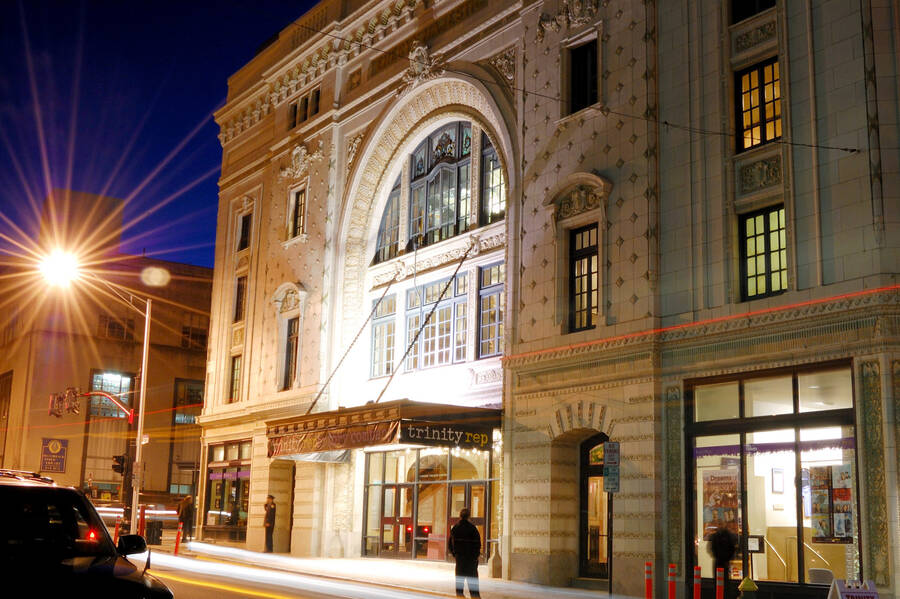

As readers of this series know, theatres with the most history often have the most ghost stories. Trinity Repertory Company’s complex in Providence, R.I., the Lederer Theater Center—which opened its doors in 1917 as the vaudeville house Emery’s Majestic Theatre—is no exception. Staff members have been observing strange occurrences in various spaces for a long time.

“I have personally witnessed the elevator arriving empty at night between 8 and 9 p.m., as I have spent a lot of time in the voms of the Chace Theater,” says Trinity Rep receptionist Kelly McDonald, who also served as house manager from 2006 to 2019. “I have also found dimes where the spirit supposedly hangs out in the Dowling Theater on house left.” What’s so special about dimes? As the program for the troupe’s upcoming production of A Christmas Carol (itself a ghost story) points out in a compendium of some of the theatre’s eerie tales, devotees of paranormal activity believe that the unexplained appearance of dimes signals the presence of spirits.

The main keeper of the venue’s ghost stories in recent years is former technical director Karl Orrall—McDonald notes that once he even led a tour for the staff of all of the reportedly haunted spots. Orrall has had his share of spooky interactions himself. Remarkably, he notes, when “someone brought in a ‘sensitive’ and gave them a tour of the building,” that individual detected all of the alleged sightings without any prior knowledge.

Among the many spirits Orrall identifies is the apparent ghost of a child.

“Often in the Dowling, when you stand onstage and look toward the booth on the corner of your vision, you can see a dark spot, or maybe it is a mass, house left in the middle row,” he says. “Sometimes when it is quiet and no one has been in the theatre, you can surprise it and you will be able to clearly see a small boy standing there. He is dressed in brown pants, a white shirt, and a corduroy cap—and then he is gone. I know several other people have seen him over the years.”

Then there’s the Blue Lady. In the late 1990s, Orrall served as the company’s stage carpenter. At that time smoking indoors was legal, he mentions, “and the stage crew would hang out on the steps outside of the electrics shop and smoke and drink coffee because there is a window on that level.” He continues, “The first time we saw her was at the places call for a show I can’t remember.” As several members of the crew prepared to move to places, he says, “we would wait until the actors passed before we would move. Suddenly a translucent, slightly blue woman came out of the closed electric shop door, headed towards the stage door to the Chace Theater. As she passed the window I remember being able to see through her. She was in a hurry and called out the name Laura a couple of times.” I recalls that a production assistant in a chair on the landing beneath the greenroom stood up and shouted, “What the fuck was that?” and then ran up to the greenroom. “Several crew members avoided the back hall for a while. I think we saw her two more times over the next couple of years.”

Orrall also recalls one run of A Christmas Carol many years ago in which the show “had two casts, two running crews, and two carpenter crews building it. At one point the entire night crew quit, so the day crew had to work some overnight shifts.” At about 3:30 a.m. during one of these shifts, Orrall went up to the restroom in the greenroom of the Chace, where this season’s Christmas Carol will begin performances this week. “I pushed open the door, and a man was standing there washing his hands,” he says. “He was wearing a green sweater with a tan Egyptian pattern on the collar with a pair of tortoise-shell glasses tucked into the collar, brown pants, and very shiny brown loafers. I said, ‘Hello,’ and he said, ‘Hello, you guys are here late tonight.’ I said something about the other crew quitting and that this was a huge build. I went into a stall and heard him grab some paper towel.”

Normal enough, right? Orrall continues: “At this point he asked how long I had been at Trinity. I replied, and then he said that the set was looking good and he told me to have a good night.” Silence. “I left the stall and realized that the restroom door was not swinging closed and that I did not hear it close before I left the stall. I ran out after him but could not see him, and oddly thought to myself that I never heard his shoes on the tile.” Orrall adds, “He was not anywhere to be found. I asked the TD if he knew of anyone else in the building, and he told me that everyone else had left. We all avoided the greenroom for the rest of the night. Years later I saw his picture hanging in the lobby; out of respect I will not say who it was.”

Disembodied Voices and Self-Opening Doors

The Rodgers Theatre in Poplar Bluff, Mo., was opened by impresario I.W. Rodgers as a movie theatre in 1949, and current Rodgers Theatre manager Shanna Eason notes that there have been so many alleged encounters that ghost hunter groups have led tours of the building and also conduct overnight investigations that turn up quite a bit of activity. “I can’t verify the information they share on their tours,” she concedes. “However, we have had some interesting stories and I personally have experienced strange things.”

What kinds of strange things? Why, phantom doors, as recently as last month. “Most of the doors to the theatre have been upgraded to hollow metal doors with panic bars,” Eason explains, so “they have to be opened from the inside by engaging the bar and in most cases, the bolt locks are engaged.” She notes that on several occasions that the theatre’s doors have been mysteriously open, “and I have to drop what I’m doing to go close them. Our cameras show them opening and closing on their own! I have been laughed at. Most of the time I am alone there, and I thought someone was lurking; however, the cameras show nothing and the voice sounds right behind me.” Eason says she isn’t bothered by these presences: “I have never been scared by any of the activities because I love the history. It has been a good time, for sure!”

The Prankster Performer

Former Broadway house the New Victory Theater, which first opened as Theatre Republic in 1900, has a rich history, and it seems that some of the memorable figures who’ve trod the theatre’s boards and backstage have never left. Actor Tim Dolan, whose love of theatrical ghost stories led him to establish the walking tour company Broadway Up Close, feels the structure’s extensive history has lot to do with the various ghost encounters over the years. “It has had its fair share of big personalities that have filtered through its doors,” Dolan says, “each leaving their mark in their own unique ways.”

Colleen Davis, the New Victory’s production coordinator, has witnessed firsthand the sometimes mysterious results of those legacies. From her first day at the theatre, working as an assistant stage manager on the day of the opening celebration of the newly renamed theatre in 1995, she found that the building and devices in it would behave in strange ways. “For one whole day, I could not get a lock or a key or a key code or a door to work, the photocopier—nothing worked for me,” she recalls. But when someone else tried, everything functioned properly. This was before Davis heard any ghost stories about the theatre, and she thought the building somehow hated her. But she didn’t give up, and after freelancing as a stage manager for the organization for a few years, she joined the staff in her current role in 1998.

A year or so into Davis’s full-time tenure, during a renovation that led the wardrobe crew to work from the trap room beneath the stage instead of their regular designated space, just before a performance by the Australian group Circus Oz, a bow tie went missing. The crew had last seen it on the performer’s dressing room table. “And it’s not there,” Davis recalls. “We hunted, hunted, hunted—couldn’t find it.” Eventually, a search party composed of Davis, the stage manager for Circus Oz, and the New Victory’s wardrobe supervisor gave up and decided to start the show without the tie. Then, as the three of them were “walking past the wardrobe room, there was a stack of metal shelves. There was a plastic bin that actually shot out and flipped upside down, and fell on its lid,” Davis adds. The wardrobe supervisor “picked up the bin, and on the floor was the bow tie, and we all said, ‘Thank you,’ and went on with the show.”

Davis says that this became a pattern: An item would disappear from one of the dressing rooms, they’d go looking for it, and “right when we’d give up, that’s when it would be refound somewhere else. Or maybe right where we’d looked.”

That wasn’t the only time a bow tie went missing and reappeared. Sharlon Wilson, the New Victory’s wardrobe supervisor at that time, recounts a similar incident. “I believe it was 2001, I put a bow tie on a rack onstage, and I went to the restroom, and when I returned it was gone,” she says. “I was the only person in the theatre at the time—as you know, the wardrobe people are the first to come in and the last to leave the theatre. I couldn’t believe my eyes: When I realized that the bow tie had moved to the opposite side of the stage, I was in disbelief…I could’ve sworn I saw a blurry image of a person. I was so frightened that I snatched the tie and moved swiftly to put it back in place and left the theatre.” Wilson adds that, on occasions when she was alone at the theatre late at night, sometimes she “would hear things moving around and some faint voices when I would put costumes onstage or pick up laundry off the stage,” and “I would often see images run past me.”

Davis reports that while she isn’t aware of any incidents in recent years, the mischief she did witness continued for some time.

“She kept playing pranks on us,” Davis says. “She disassembled an accordion on me once, like, the blocks and the reeds inside. They were all unscrewed, like all of them were all over the case.” Why does she gender the spirit as a woman? “Everyone’s assuming it’s Mrs. Leslie Carter, because the theatre featured her while she was a star in New York” in the first decade of the 20th century, when the venue was called the Belasco Theatre. Davis acknowledges that they can’t be sure it’s her, “but the guess is that she’s a performer, because she never messes with the show.” Whatever the issue, “she always fixes it, or we fix it, by showtime. We’ve never actually had a prank that affected the show.”

The Devilish Deacon

When director Mike Ricci, now based in Minneapolis, became artistic director of a local theatre in North Carolina (which declined to have its name included in this story) in spring 1990, the receptionist and box office manager, plus a few board members, told him stories of a clergyman who allegedly died in the building when it was a Baptist church; he had been a deacon who had led the congregation. Since the staff consisted of just Ricci and the box office manager/receptionist, Ricci explains, his role was “pretty much of a one-person operation,” with tasks ranging from budget management and fundraising to physically upgrading the space and designing and constructing sets. As a result, he notes, “I spent a lot of hours in that building, from early morning to past midnight on some days.”

On one hot summer night in that first year, Ricci was alone in the theatre and needed to get to the light board. He explains that reaching the board on house right required going across the balcony, because the space retained the church layout—“pews for seating, stage built over the baptistry, balcony where the lighting booth was set up, stained-glass windows surrounding the audience and backstage”—and had access to the balcony on just the house left side.

“As I started crossing the balcony,” he recalls, “the temperature suddenly dropped. I got chilled to the bone, and the hair stood up on my arms and my neck. I had never experienced that before. Thinking that it might be the deacon, and that he might be resting up in the balcony, I carefully made my way over to the light board, made the adjustments I needed to make, and made my way across, and then back down the stairs and onto the stage.” When he resumed his work, Ricci says, “I began to feel very uncomfortable, almost like a weight on my chest, difficulty breathing, etc.” He stood up and announced, firmly and clearly: “I know you’re here, Deacon, and I’m sorry about what’s happened to you. But I have work to do, and I’m going to be spending a lot of time in this building, so let’s make a truce that the both of us can be in here at the same time without bothering each other. Okay?” Ricci says he paused a bit, then “began to feel more normal—the weight was gone, and my breathing returned to normal.” After that, Ricci says, “I always felt that I had made some kind of peace with the deacon, and we were able to coexist in the building without really getting in each other’s way.”

Apparently the truce didn’t extend to Ricci’s wife and daughter. About a year after that incident, Ricci’s wife, painter and designer Ellie Ricci, was working on the company’s 1991 production of Frankenstein, and reports a bizarre experience while she was washing off brushes. She says she went to the back of the building to the slop sink; to do so, because of the church setup, it was necessary to go down a hallway to the shop, and at the opposite end of the shop was a small room with a sink. “I went down the hallway—nobody else was around at the time—walked past the shelves on my right that went over my head about a foot or so,” she says. On the corner post of the top shelf was a corduroy Florida State baseball cap. “It was sitting on top of that post for a very long time, years, I’d say. When I walked past it and got to the back where the door to the sink was, I heard something drop behind me. I turned around and it seemed that the hat was dropped to the floor. But in order for that hat to come off that peg it would have had to be lifted and dropped, and it was dropped right side up onto the floor.” She looked around, called out, and when no one responded, she proceeded toward the sink.

With her back to the door, she says, she “kept turning around because I kept thinking there was someone behind me, maybe wanting to use the sink, I don’t know, but nobody was there. I washed up as quickly as I could because I started getting the creeps.” She headed back to the theatre, put the cap back on the post or on a work table, “walked out the door and started walking down the hallway. Then in my ear, very close to the back of my head, at my right shoulder I heard a big hiss that was too close for comfort, so I screamed and ran back to the stage. Needless to say, I was pretty rattled.”

Their daughter, Danielle Ricci, now a choreographer, director, and educator, was 8-10 years old during Mike Ricci’s tenure at the theatre and attended elementary school across the street from the theatre. She spent time there each day after school while her mother was at work. “As a kid I grew up with a gift of feeling energy and hearing things,” she recalls. “I didn’t like it, because it scared me and made me uncomfortable.” She notes that she’s an only child, “so I was left to myself at the theatre and would find ways to fill the time as my dad either worked in his office or in the shop building a set. There were many times where I felt that I was being followed—especially on the stairways on either side of the building.” She describes how she’d climb the stairs “in a weird way so that my back was against the wall so that I didn’t feel the presence behind me.”

A few memories particularly stand out, she says. “There was a time in which I was sitting and drawing in the break room and was hearing my mom’s voice call me from the shop area of the theatre,” she says. “I knew my mom was at work and thought it was impossible that she was there. But I keep hearing my name being called. So, I called her from the phone on the desk I was sitting at, and she was in fact at work.”

Then there was the time her school choir was learning a musical theatre medley that included the title song of The Phantom of the Opera. “There was a day where I was in the lobby by myself, singing this part of the concert to myself,” she recalls. When she got to the Phantom’s line “Sing, my Angel of Music!” she says, “I heard these disembodied words right behind my right ear as clear as day.” She was so upset, she says, “I ran out of the room trying to find my dad.”

On another occasion, she was in her father’s office, which had previously served as the deacon’s office. She explains that her dad’s “desk sat facing the door, and a wall of windows was to the right. There was a heavy window that was always propped up with a piece of scrap lumber cut to hold the window open.” As she sat at the desk, “filling my time, I saw the top of the piece of wood forcefully drop out, causing the window to slam on the wall. There was a loud sound like the furnace roaring, and the chair I was sitting in spun around.”

In sum, Danielle says she was always uncomfortable at the theatre because the deacon’s presence “was always around me. There are many times I would be in a room doing whatever I was doing and I would get so overwhelmed with a feeling of his presence that I would go find another person to be with.” Those sensations, she says, “made me aware that the stories about the deacon were very true.”

Voices in My Head

When Bob Shuttleworth was technical director of the Albany Little Theatre (now Theatre Albany) in Georgia from July 1984 to August 1986, he says, he “had heard rumors and legends of encounters at the theatre, a large antebellum home to which a theatre house (stage and audience) had been attached at the rear.” The building has been offering performances since 1932, so there’s been plenty of time for those tales to accumulate. “One legend involved a bride who died on her wedding day at the home,” Shuttleworth says. “One co-worker stated that she’s felt a presence pass through her, leaving the scent of lavender behind.” He notes, “I am not necessarily a believer in such things, however I try and keep an open mind.”

On one night in 1985, at around midnight, he was onstage working on a piece of scenery for the upcoming production when something bizarre happened. “I began to feel something,” he recalls. “Something intangible. I tried to simply shake it off, but it didn’t stop. A few minutes later I noticed that the stage had grown noticeably cooler, and that the feeling that something was there with me grew stronger.” He was kneeling on the stage at the time and raised his head to look around, but there was nothing to be seen. “Then I began to feel nervous, even a bit shaky, but couldn’t figure out why. That’s when I heard something. Or actually, I felt something, some kind of a voice in my mind. It was saying to me, ‘You need to leave…now!’ It was calm, but insistent. I laid down the tool I was holding and stood up and again looked around. Then I felt the presence again saying, ‘Now!’”

Shuttleworth explains he left the tool, turned off the lights, and headed out the door, locking it behind him. “As I took the few steps to my van, I began to feel calmer in one way, but definitely unnerved. I truly believed that I had heard/felt something. It definitely motivated me to leave. I worked there for about another year. Never had that experience again.”

The Ghost Light and the Wind Walkers

Though theatre ghosts are typically associated with old, storied venues, Sheila Rocha, chair of performing arts at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, N.M., reports strange happenings at her campus’s Performing Arts and Fitness Center (PAFC), even though its construction was completed in 2018. When the PAFC was less than a year old, she says, “booms were set up for side lighting. LEDs set, tested, and ready. We turned off everything, about to walk out, when a light from the suspension grid faded up.” A member of the tech crew went up to the catwalk and unplugged the instrument. As they all got ready to head out, the stage left sidelight turned on. “We’re a bit baffled. Checked the light board—it’s powered off. We unplugged it, but it just remained on. We studied that contraption and all the power cords from every angle. It had no juice but continued to remain lit.” She adds, “We let it be what it was, locked up and went home. It finally went to sleep sometime during the night.”

Rocha highlights that IAIA “is the first tribal college to create a BFA program in Indigenous Performing Arts with a state-of-the-art black box theatre,” and notes that the program’s earlier space was highly inappropriate for performance, a “Navajo-inspired structure on the property” that had “terrible sight lines and support poles, poor acoustics, and this peculiar ambience.”

One time while rehearsing with an Acting 1 class, “we were struggling to block inside of four major support beams. We sat on the floor to brainstorm our dilemma. Without warning the skylight turned dark as apparently storm clouds began to gather above us.” Rocha continues, “A powerful wind fell upon the hogan, subsided, and then we heard the oddest sound of footsteps. On the roof of the hogan we heard someone or something walking. They moved over the roof from one side and then to the other. A second set of footsteps joined in.” She adds, “We peered upward but saw nothing through the skylight. Steps intensified. The apparent weather change became too much for us, so we decided to light a fire in the wood stove. One of the acting students picked up a few logs and opened the stove.”

They then heard the wood drop to the floor. “Everyone turned to see the student standing in bewilderment as they backed away. Another student jumped up to see what was in the stove.” What did they find? “A small multicolored bird lay dead inside. It wasn’t a native species from the area. But it lay there spread out as if someone had designed its presence—one wing opened like a fan. The other wing tucked gently behind the tiny body, its beak closed pointed upward. An art piece with no purpose.” One student carefully took out the bird and announced that he’d bury it outside. “He left the hogan, a gust slamming the door shut behind him. The wind whipped up once more.”

They all went to the center of the building, in agreement that something was deeply off but not knowing what to do. “As quickly as the wind and footsteps arrived,” Rocha says, “they abruptly subsided. The sun broke through the gray, and whatever was walking above our heads relented. The student returned, and like good theatre folk we went back to work, but with eyes on the clock.”

Rocha also recalls an eerie experience in around 2005 at a theatre in Nebraska (which asked not to have its name included in this piece): “Our Native American ensemble, Four Directions, rehearsed and performed in what used to be the theatre balcony,” Rocha says, “transposed into a black box with subtle reminders of its century-old Mediterranean and Moorish architecture.” She continues, “During the Jim Crow era, it consigned people of color to the balcony, but later became the more contemporary locus for communities of color to explore performance creation. Mortar holds memory.”

During a break, one of the actors, named Moses, went to the basement to get cold drinks for the group. Rocha says he heard him shout, “Come down here right away!” She says she took the elevator down and stopped in front of the fireplace in the former smoking room. “I didn’t see Moses,” she says, “but I heard the sound of a bouncing ball from the basement lobby area.”

“Moses?” she said in a stage whisper. “Moses, are you down here?” Rocha notes that it was cold in the basement, and the lighting consisted of a faint yellow from sconces on the walls. “I heard heavy feet walking across the mosaic flooring. The bouncing faded as if the ball rolled away. ‘Moses!’ Stage voice two. I’m feeling a little creeped out now. I moved toward the light.” The actor responded: “‘Dang, did you hear that?’ My tall Lakota colleague, with his hands pushed deep into his pockets, emerged from around the corner—his eyes wide. ‘You see anything? But you heard it, didn’t you?’ Rocha says she could do nothing but nod.

Rocha says that although “Moe’s a grown man and a leader in the community,” that night “he shook his head, accompanied by a nervous chuckle, half unnerved. His long braids trailed behind him as he cued me to start up the stairs with him.” She continues, “I tried to ask about the drinks, but having lost all interest he hustled up the steps, his boots clicking the speed of hooves at a steady gait. As we reached the main landing we heard a sound, like a door closing or opening from below—and that damned ball, or was it air ducts, or a rat?” She adds, “We froze, looked at each other for a split second, then ran up the next flight of stairs laughing, or screaming—stage voice three, who knows. All I recall is that we were alarmed, and it was all I could do to keep up with him. The theatre was mostly dark until we reached the mezzanine.” She recalls saying, “Yes, I heard it. But I didn’t see anything, and you didn’t either, did you?”

She says he explained that, upon reaching the top of the basement stairs, Moses heard a child’s voice and the sound of a bouncing ball. “He called down to see what child might be there, if perhaps someone was still in the building. Youth classes rarely extended beyond our evening rehearsal time three floors below us and tucked away. No one answered him. But he continued to hear the bouncing ball and kid sounds, so he decided it was best to see if someone, somehow got locked in the theatre.” When he found the space empty, he called out to her. “But I came in from the direction that he had heard the voice and it was only the dim cold—no one was there.

“We hopped the elevator from the mezzanine to avoid any unnecessary encounters with the mystical,” she says. When they reached the black box, two of the younger performers, accompanied by two older actors, “approached me as the director to describe how they had been mysteriously accosted. One child’s braid was pulled by…no one; an older teen in a back room saw someone open her door while she was changing, but no one was there.”

Rocha describes what happened next: “As our Indigenous ways instruct us, we did the appropriate ceremony and prayer to address the tricky spirits who came to taunt us,” she says. “We were able to get them to leave that evening, but other rehearsals for other shows opened new portals for supernatural guests who took their turns invading our spaces: shadowy figures watching us from empty audience seats, voices muttering in other languages, and an occasional tittering child reminding us the sacred can equate to the unknown.” Rocha repeats: “Mortar holds our memories.”

Russell M. Dembin (he/him) is a former managing editor of this publication.