Ben Vereen sat across from us one August morning at breakfast in the Winston-Salem Marriott, enthusing about his first visit to the National Black Theatre Festival in North Carolina; the previous he night he had been given the festival’s Sidney Poitier Award. “I was so touched,” he said. “When my buddy Stokes started reading the introduction, I thought he was talking about someone else. I’m sitting here with Black theatre royalty, and what can I possibly say? When I looked up on the screen and saw all my friends who had passed in recent years being acknowledged, I said, we have to give them a standing ovation, because it’s their spirits in this room that are carrying us.”

Actor and playwright Regina Taylor told us she comes to the festival to be inspired, to network, to find and give support. “It’s like one long party,” she said. “I’m seeing people I haven’t seen in ages and meeting new folks. It’s about bridging past, present, and future, and it’s always exciting. It’s called holy ground, because we look back on the shoulders we stand on.”

Coming to every festival since 1991 has been Eileen J. Morris, artistic director of Houston’s Ensemble Theatre, who spent the early gatherings asking advice from such theatre giants as New Federal Theatre’s Woodie King Jr., Penumbra Theatre’s Lou Bellamy, and St. Louis Black Repertory Company’s Ron Himes. Over the years, as Morris learned and began producing and directing plays for the festival (a total of 10 by 2022), she’s become someone others might seek advice from. When asked what the event meant to her, she got emotional. “Lord willing, I will never miss a festival, because it rejuvenates me,” Morris said. “It makes me feel whole and lets me know others are there in my culture. The festival uplifts in ways that make the world a better place.”

Actor and singer Chester Gregory (Hairspray, Motown) has been coming since the early festivals, and said he learned from festival founder Larry Leon Hamlin not to hide behind modesty. “Allow your talent and hard work to shine,” he was told. “Being humble is a great thing, because you are acknowledging that you are sharing with people. But don’t ever be modest, because you downplay the hard work that you put into it.” Gregory keeps coming back to the festival, this time with The Eve of Jackie, about R&B/soul pioneer Jackie Wilson.

Petri Hawkins-Byrd, who co-chaired the 2022 festival along with Lisa Arrindell, pointed out that the National Black Theatre Festival is a misnomer, because it is so much more than theatre. This week’s festival, which ran Aug. 1-6, included spoken word, singing, dancing, oratory, art installations (with works by Lonnie Robinson and others), a craft fair of 100-plus vendors, film screenings, and more. “I’ve been coming here since 1999,” said Byrd. “I first came with a friend for two days. The friend left and I stayed, and have been coming back ever since. Every time, I feel this is a once-in-a lifetime experience. So we work together to continue the legacy.”

Similarly, actor Fay Hauser hails the festival for “plays that stimulate you, that give you a sense of history, that give you laughter and tears and prospects for the future. You can find groups of people who want to read plays and hear something new and creative. You can expand your possibilities by being part of the midnight poetry jam. And you can do that all night if you want.”

How did we get to this moment where such names as above, as well as the likes of Tommy Hicks, Roscoe Orman, Vivian Reed, Ted Lange, Lamman Rucker, Tonya Pinkins, Harry Lennix, Charles Dumas, Chuck Cooper, Starletta DuPois, Lillias White, and Hal Williams, come to Winston-Salem every other year to be uplifted and energized? Let’s go back to the beginning.

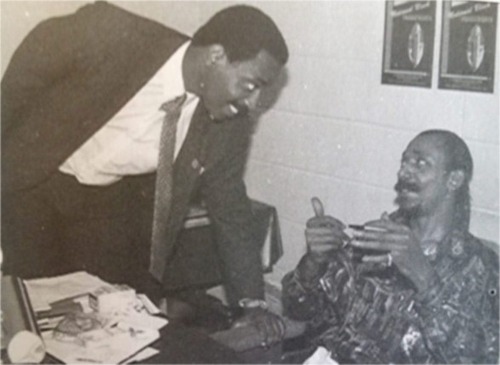

It was St. Louis in 1987. “I want to create a national Black theatre festival,” said Larry Leon Hamlin, who had founded the North Carolina Black Repertory Company in 1979, to Herman LeVern Jones, producer for the National Black Touring Circuit, as they both lit up cigarettes in a theatre lobby during intermission. This was the recollection of Jones as he sat across from us at the Marriott. He continued by recounting his reply to Hamlin: “I know what national means. And I know what the words Black and theatre and festival mean. But what do you mean when you put them all together?” Hamlin thought for a moment and said, “It’s about the spirit of our ancestors, the African Americans, and their storytelling. We stand on the backs of those ancestors, and if we can put it in the South, this will be a holy place to gather. This is not New York. This is not L.A. This is not Chicago. This is not any of those big, grand cities. I want it to be in the South, where slavery ruled. We’re going to unite Black theatres and do it in Winston-Salem every two years, and we’re going to have people celebrate this city, and we’re going to change the dynamic of the very racist environment in this city.”

Hamlin pushed for engagement with the city of Winston-Salem in 1989, and was met with a lot of skepticism from the City Council. “People were concerned, with so many Black people descending on the city, what would happen—after all, it was the South in 1989,” noted Jackie Alexander, the festival’s current artistic director.

Planning for the first festival was anything but certain. By May, with just 10 weeks to go before the festival was to begin, all they had raised was $5,000. Jones started contacting people. First on the list was Maya Angelou, who was a professor at nearby Wake Forest University. She said she was interested but that 10 weeks was just not enough time—even though she finally agreed. Jones in turn asked her to contact Oprah, who also said yes. “That’s when we had a National Black Theatre Festival,” Jones told us. They also lined up support from Cicely Tyson, Antonio Fargas, James Earl Jones, and Mario Van Peebles. After an intense PR push, the festival was all over numerous newspapers, including the front page of The New York Times Arts & Leisure. Once they started selling tickets, they could hardly keep up. They got to 12,000 and decided to cap it at 17,000 tickets.

Winston-Salem’s current mayor, Allen Joines, was involved in the beginning as part of the city’s economic development council. He admitted to “a lot of skepticism when the idea was first pitched. But when Hamlin landed Maya Angelou, Oprah, and James Earl Jones, we saw the validity.”

Sylvia Sprinklin-Hamlin, who had worked with Larry at the National Black Repertory Company not long after they were married, was appointed to the festival board of directors in 1991. When Larry died in 2007, Sylvia stepped in and became executive director. According media director Brian McLoughlin, Sylvia knew she had to continue the festival’s strong culture, so she called a meeting to bring everyone together and announced, “Larry’s gone, but the festival will continue.” Then she directed everyone to introduce themselves and to say what they wanted to do going forward. McLoughlin thought he’d be cute and said, “I’m media, I’m broadcast, I handle PR, and Larry Leon Hamlin hand-picked me for this.” Showing her authority, Sylvia replied, “And I can unpick you.” That was McLoughlin’s first meeting with Sylvia, but over time they both grew to respect each other abilities. “With Larry, it was, ‘Shoot first and ask questions later.’ Everything was about creativity. With Sylvia, it was all done methodically.” By their third festival together, they had built sufficient trust that Sylvia just gave him his budget and let him work, he said.

COVID meant that the 2021 festival was cancelled, and even doing it in 2022 was uncertain, as the pandemic is still present. When Sylvia died in January, organizers had to make a big decision. Newly appointed artistic director Jackie Alexander had little time to fill his predecessor’s big shoes—or, as McLoughlin joked, “big pumps.” By March, though, the festival was a go, which meant only five months for planning. Just like the first one in 1989!

Alexander, who is focused on the goal of serving the legacy and keeping it growing, told us, “Larry Hamlin was bigger than life. I only met him once, but at that moment, I got what everyone else got. So it takes all of us to try and keep things going. With all the challenges of Sylvia’s passing, COVID, gas prices—it’s a lot.” But as soon as the festival began again, Alexander said, “That energy was back. Everyone was hungry for the reunion. It’s been beautiful.”

Still, he admitted: “It’s not recommended to organize it in five months! Luckily, we had contractors who’ve been doing the festival for years, and they know where everything is and how it all runs. But the festival really operates on the strength of volunteers. In 2019 we had 1,300, including drivers, PR folks, event organizers, and backstage teams.” Their technical director gets 30 shows up in five days: 15 up on Tuesday, with sets struck on Thursday, then another 15 the next night. The crews, nicknamed Grizzlies, are mostly college students, brought in for the week as part of the volunteer cohort. “They’re not just volunteering,” Alexander said. “They’re volunteering for something that’s very personal and dear to them.”

Said Mayor Joines, “Today I see the festival as a combination of excitement and reverence. The city of Winston-Salem has become the biggest contributor over the years, each time giving $150,000. And it’s worth it, because we are enhancing our culture. As the largest and most dynamic Black theatre event in the world, we get a lot of international press. Plus, financially it makes sense. Our convention bureau reports the 60,000 visitors have an economic impact of $13 million, spent on hotels, restaurants, retail, and so on. Finally, we believe the positive impact of this being the home to such a great event helps us recruit businesses and industries to locate here.”

Indeed, people in the city welcome the festival each time. As Alexander said, “When I talk to people on the street, regardless of race, they love it. They know that Winston-Salem is seen as the city of arts and innovation, and the National Black Theatre Festival is the crown jewel.”

But the festival isn’t just a gathering of people; it’s also a marketplace for new material and Black theatres. This year, NBTF instituted the Sylvia Sprinkle-Hamlin Rolling World Premiere Award, which brings together five nonprofit theatres, thus giving a playwright five productions of their new work “right away,” as Alexander put it. “If we can give the playwright reviews and coverage in five major cities, then we’ve created a hit, with buzz about the playwright and the theatres. We want to keep connecting the companies, keep them working together. We are all nonprofit theatres. It’s easy to get stuck in that bubble, because you’re just trying to survive from day to day. That’s why that collaboration helps, because we can’t make a hit here by ourselves, but five of us?”

Another way the festival nurtures writers is the Garland Lee Thompson Sr. Readers Theatre of New Works, run by poet and producer Garland Thompson Jr., whose father started the Frank Silvera Writers Workshop with Morgan Freeman in 1973. Thompson and Freeman wanted to offer an opportunity for playwrights of all colors to showcase their work and to engage the audience in critical analysis, in order to help playwrights develop their craft. At the 2022 festival, Readers Theatre of New Works premiered 30 plays, cast and directed by festival attendees.

It’s not just nonprofits who come to scout. Broadway producer Stephen Byrd (MJ, Ain’t Too Proud, Trip to the Bountiful) attended for the first time this year, and called it “the most incredible experience—a spiritual awakening.”

That echoes the superlatives of many. Frequent attendee Tonya Pinkins called it the biggest and best family reunion you could imagine. Ed Smith, who helped establish Black theatre in Buffalo, N.Y., urged all to attend: “If you like people, come. If you like laughter, come. We have all of that.” Said producer Garland Thompson: “You walk down the same hallways as a Black legend did. You can see what they saw and draw strength from it. You know you are connected to a very, very rich history.” And because the festival was announced so late this year, Off-Broadway writer, director, and actor Layon Gray rearranged his entire schedule to be there. He’s been coming since the beginning, he said, adding, “I’ll be here until my ghost is set free.” To Jackie Alexander, the NBTC is “the greatest Black theatre event on the globe.” The next one is planned for July 29-Aug. 3, 2024.

And Ben Vereen? He came to the festival for one day to receive the award, but was so positively impacted by the program and the attendees that he cancelled all other plans and stayed for the entire six days. “I have to stay,” he told us. “Everybody needs to be here. And when you come, you’ll come back and you won’t want to leave.”

Hinton Battle is a three-time Tony winner whose Broadway credits include The Wiz, Bob Fosse’s Dancin’, Dreamgirls, Sophisticated Ladies, Chicago, Miss Saigon, and The Tap Dance Kid. He is currently the co-founder and director of the Hinton Battle Dance Academy (HBDA) in Tokyo.

Dorothy Marcic, Ph.D., is a Columbia University professor, Fulbright Scholar, and playwright of Respect: The Musical and Sistas: The Musical. She’s the writer of 21 bestselling books and award-winning screenplays, and is co-creator of the Wondery podcast “Man-Slaughter.”

Kimberley LaMarque Orman, a professor at Fordham University and executive producer of the video series Fordham Road, has produced, acted, and directed in a variety of productions across the U.S., including Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Jar the Floor, Macbeth, In the Blood, Blues for an Alabama Sky, Romeo & Juliet, Three Sisters, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, and The Old Settler.