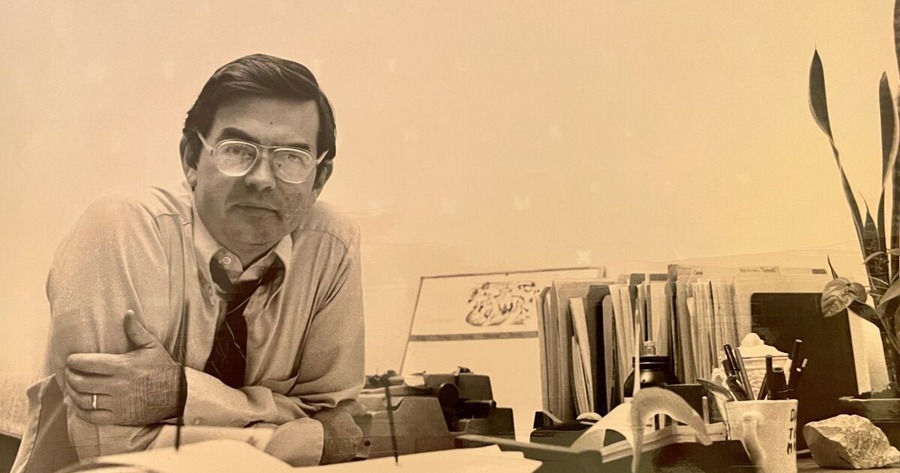

Dan Sullivan, longtime theatre critic for the Los Angeles Times as well as the former director of the Eugene O’Neill National Critics Institute, died on Oct. 4. He was 86.

“If the play seems at times incoherent and tedious, the reviewer will mention the heresy that this may be more the fault of the author than of the director.”

The play? Hamlet, no less. The reviewer? Dan Sullivan, no less. The production? The 1963 opening of the Guthrie Theatre, no less.

Most of us critics tend to leave Hamlet alone, on the grounds that its bona fides are—well, as the Supreme Court might say (or once would have said), settled law. Safer to blame the production.

But not Sullivan.

“Hamlet is a great poem, trapped inside a bulky melodrama, and you can’t cut the melodrama without hurting the poem,” he wrote for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. He had a point, and, the same review reminds us, a neat way with words: “’Great’ is the word for Ellen Geer’s Ophelia. The girl shows backbone in her early interview with the prince (‘Indeed, my lord, you made me believe so’ is delivered without the customary whimper) and in the mad scene she is actually mad. Hair in dirty disorder, gown stained with grass, she falls to her knees with a sob and claws the floor of the palace with her fingernails.”

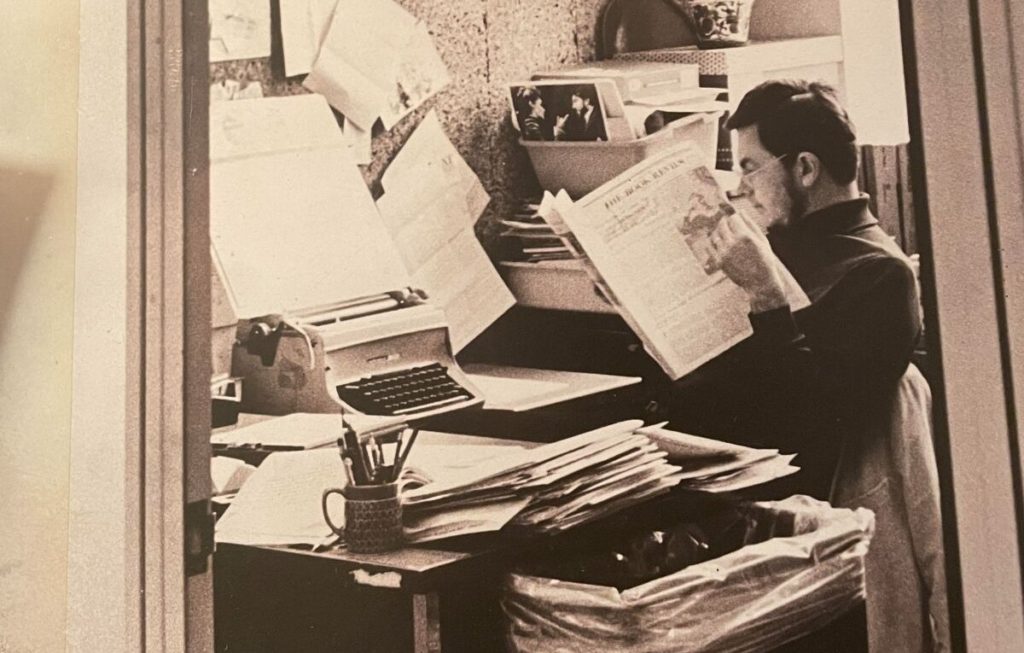

The style is authoritative, descriptive, fearless, clipped, third-person, unconcerned with the niceties of mental health; indeed, given our current era of necessarily self-protecting critics, you would not read such a paragraph today. But Sullivan came from a different era, one in which hedging was as much a sign of weakness as a run-on sentence or an over-reliance on adjectives. He did not often use first person—few of his peers did—and would have cut “I feel that” and its relatives, not that such words would ever have found on their way from fingers to typewriter to printed page.

Sullivan variously wrote for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Minneapolis Star-Tribune, New York Times (for whom he covered Off-Broadway), and, most notably, the Los Angeles Times, where he worked for 22 years, much of it locked in a fierce critical rivalry with Jack Viertel. This geographic range meant that Sullivan did not come with the typical New York parochialism of his profession, though he certainly wrote in the style of the big city newspaperman (or, in the case of the Chicago Tribune‘s notorious Claudia Cassidy, newspaperwoman). The lede was the lead; it was not the critic clearing their throat. Fancy words were to be eschewed (so were parentheses). Clarity was a creed, spelling errors a curse. Paragraphs as long as this one were pushing their luck.

For his generation of critics, reviews were not a freelance assignment but a beat, as regular as a sports columnist, whom such critics often resembled. Reporting what was on view was the first obligation. Verbs needed to be strong. Prepositions should not end paragraphs. Nouns were your friend; descriptive adjectives were far more effective than meaningless qualitative expressions of praise like “excellent” or, worse, “really good.” And writing on deadline was a muscle that had to be kept in shape by going to a kind of writer’s gymnasium of the mind. Delay just meant more blather.

Above all, Sullivan believed, the critic served the audience. Not the actor unable to face the truth. Certainly not the nervous producer. There was no obligation to be supportive of the theatre, and a certain Anton Ego-like theatrical flourish down the aisle was acceptable, even if Sullivan was, like many (but not all) critics, an introvert.

Improbably, perhaps, Sullivan was utterly dedicated to teaching young critics, which is how I came to know him when I took over the National Critics Institute at the Eugene O’Neill Center a few years ago. I inherited a filing cabinet with yellowed notes, and even Sullivan’s longtime associate, the gregarious theatre professor Mark Charney, who loved Sullivan, who could be gruff, like a brother. The cabinet turned out to be one of great curiosities for anyone interested in the gentle art of theatrical reviewing: a bevy of advice for cultural writers could be found in the drawers therein, with a particular specialty in techniques for coping with the dreaded pressing deadline and the stubbornly empty page.

Sullivan, who had continued at the O’Neill, which he loved, well past the usual retirement age, clearly found it hard for another to take over his position. I’m old enough now to better understand that—I believe Edward Albee called it the 360-degree view, where you can see both your youthful mistakes and what lies ahead—but he was nonetheless gracious and supportive, especially once he understood that changes in the program, and its style, were needed to move with the times. Sullivan did not have to teach people how to deal with hateful collective attacks on Twitter and Facebook.

But we’ve kept much of what Sullivan put in place: writing on overnight deadline, a flurry of activity, forthright conversation on what it means to be a critic, which obligations to take seriously and which to ignore, no matter how much pressure comes your way. And we still try to help folks right great first paragraphs, to join them well to what follows thereafter, and to end with a heck of a kicker. The place still is very much him, even if almost everything about theatre criticism has completely changed.

As someone who has read more of his work than most, I’ll end with this: Dan Sullivan was incredibly smart. He didn’t so much review theatre as wrestle with it.

(A decent kicker—if only it ended with a stronger noun.)

Chris Jones is the longtime theatre critic for the Chicago Tribune and the Broadway critic for the New York Daily News. He now also serves as editorial page editor for the Tribune. He wrote for American Theatre for many years, but this is his first piece for the magazine in a while.