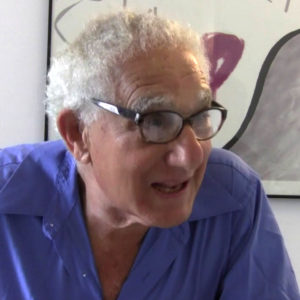

Robert Kalfin, founder of the Chelsea Theater Center and longtime Off-Broadway producer and director, died on Sept. 20. He was 89. Another tribute to him and his legacy can be read here.

I was 18 years old and a sophomore at Oberlin College when I was awarded an internship at the Chelsea Theater Center in New York. I was astonished that my parents agreed to let me spend a semester out of the classroom, though I would receive a full term of college credit by learning firsthand about making theatre. I was also surprised that the Chelsea Theater Center was not, in fact, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood (it once had been), but was by then sort of tucked away on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. (Let it be said that BAM and its environs back in 1972 had little relationship to downtown Brooklyn today.)

I have a vivid memory of walking into Chelsea for the first time on a frigid day in February. The big black box of a space, which I later learned was constantly reconfigured to accommodate each new innovative set design, was laid out for this particular production in a kind of “wide panoramic” architecture. Across the back wall of the stage were three giant screens where video was displayed. All of it was remarkably striking, but even more captivating were the actors. A woman playing an elderly Jewish mother was being tugged at by her son, who pleaded with her as she resisted and wailed. Upstage, video images appeared: a close-up of the woman’s face in live feed, the explosion of the Hindenburg, black-and-white images of vintage 1950s Lakewood, NJ. This was Kaddish, an adaptation and animation of Allen Ginberg’s epic poem. Conducting all this wild activity was the director, a swarthy, curly-haired gentleman named Robert Kalfin, who I discovered was also founder and artistic director of the Chelsea Theater Center. Little did I know how vigorously and gloriously my life would be transformed by knowing him.

For over four months that winter into spring, I assisted on a range of productions, including a reimagined The Beggars Opera by John Gay with a score newly realized by Roland Gagnon and starring Kathleen Widdoes as Polly Peachum and Marilyn Sokol as Lucy Lockit. I was, as any novice intern, a gofer, sweeping and mopping rehearsal rooms, getting coffees and bagels, running errands, delivering scripts to performers, often traveling several times a day on what we then called the IRT to and from Manhattan. I was deliriously happy. I observed and learned best I could. When later the following year, The Beggars Opera transferred from BAM to the McAlpin Rooftop venue Off-Broadway, I became the non-Equity assistant stage manager. (Not a very good one, I might add.)

There were other opportunities that first semester as well. I assisted the remarkable designer Theodora Skipitares on The Water Hen by Polish playwright Stanisław Witkiewicz. Theodora, who would become an acclaimed puppeteer and director, designed and was constructing costumes made from woven newspapers, and crystal chandeliers which required many extra hands and hours to fabricate.

When my internship ended, Bob became a friend. He counseled me and encouraged me to take risks and ask deeper questions. One Bob motto that has served me to this day: “Hold onto life like a terrier and do not let go.” Back at Oberlin, he visited me on campus to see my directorial debut (I and Silence Some Strange Race by Gordon Porterfield) and provided dramaturgical feedback. Always protective and reassuring. Always a positive spin to life. Always provocative.

While at Oberlin, I had the opportunity to read a short story by Isaac Bashevis Singer called Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy. To my mind, it had “Bob Kalfin” written all over it. I sent it to him, and he had it adapted into a play by Leah Napolin, presented first at Chelsea, then transferred to Broadway in 1975, launching the career of Tovah Feldshuh and produced by the legendary Cheryl Crawford. (An aside I can’t resist adding: The last play I took my grandmother to see before she died was Yentl. After the show, I brought her backstage to meet Tovah, who graciously escorted us into her dressing room. She asked my grandmother if she “actually liked the production.” “Very, very much,” my grandmother replied. “You did?” queried Tovah, somewhat surprised that this 84-year-old émigré was not offended by the play’s subject matter. “You liked it even when the girl got the girl? Didn’t that part upset you?” To which my Russian Jewish grandmother replied, in her inimitable Eastern European accent: “Vell, ya know? Sometimes dat’s vhat you gotta do!”)

After graduating from Oberlin, I moved to New York, where my first job was as assistant stage manager on Christopher Hampton’s Total Eclipse, about the love affair between Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine, which Bob staged at Chelsea. Later that year, Bob arranged for me to have an audition for a summer theatre in Woods Hole, Cape Cod, where I ended up playing Lucky in Waiting for Godot and directing Pinter’s The Collection. Later I would assume co-directorship of the Woods Hole Theatre Company.

In 1973, I ended up serving as a paid casting assistant at Chelsea on Hal Prince’s first revival of Candide, designed by Eugene Lee and seriously “immersive,” well before the word was commonplace. I recall sitting in auditions at the Shubert Theater on Broadway, where Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music had recently opened, and hearing Mr. Prince (later “Hal”) turn to Bob and me (well, turn to his actual casting director, Joanna Merlin) and say, “I want young operatic singers who look like comic book characters.” I rode the IRT back to the Chelsea offices and rifled through piles and piles of agent-submitted pictures and résumés when I came upon a photo of Maureen Brennan, who had just graduated from the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and who seemed to fit the bill. She ended up as Cunegonde, in her Chelsea Theater and later Broadway debut.

In 1973, Bob directed Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea at the New Repertory Theatre on West 43rd Street, well before there was a Manhattan Plaza. In fact, the theatre was in a space that had been a funeral parlor (and would return to being a funeral parlor years hence). Marilyn Chris, who I had witnessed (and worshipped) as Naomi Ginsberg in Kaddish, was the lead, and I was cast as the consumptive sculptor Lyngstrand. It would be my Off-Broadway debut and finale as an actor. A review by Edith Oliver in The New Yorker and Clive Barnes in The New York Times made me feel like I had succeeded in a world of which I had heretofore only dreamed, and Bob convinced me to think seriously about being a director—to have a “bird’s eye” view and a vision for the entire story onstage.

Bob continued to uplift my career. When I was placed on the waiting list for the Yale Drama School but ultimately not accepted—and felt my life was indeed worthless—he introduced me to Robert Moss, artistic director of Playwrights Horizons, which was just taking up residence on the yet to be created Theatre Row. Moss hired me as one of two associate producers (Andre Bishop was the other), and there I was able to direct my first professional shows, including The Dybbuk at Playwrights Horizons/Queens, which Bob Kalfin came to see and for which he provided valuable feedback and encouragement.

My life and success in the professional theatre is due to the gentle soul, graciousness, wild enthusiasm, and bountiful mentorship of Robert Kalfin. Without Bob, I would never have had the impetus to interrogate the “why” of my being of the theatre. There would never have been my tenure at Playwrights Horizons, and I never would have received an NEA/TCG Grant to spend three seasons with Gordon Davidson at the Mark Taper Forum. All of these steps led, many years later, to my spending 23 years as artistic director of the Sundance Institute Theatre Program.

What I understand now is that Bob Kalfin helped me to see into my own psyche, to construct a vision over time of how I imagined theatre and creativity functioning in the world, to trust my instincts, and—maybe more important than all of that—to carry optimism with me. His unwavering love of storytelling, his insatiable curiosity, his indisputable taste in literature, his embrace of visual art and theatrical space, his stirring risk-taking, all inspired me on a journey of curiosity, to know myself and to know the history of theatre and of being a gay man in the world. And to identify my place in the ecology of the American theatre. Bob’s good will also kindled in me the desire to uplift and support others as I grew and matured. That has, in fact, defined my entire life in the theatre: an embrace and support of talented storytellers with the belief that what lies inside our playwrights, directors, designers, and actors does in fact influence and transform the world.

Some 50 years after we met on that cold winter’s day at Chelsea at BAM, I sat by Bob’s hospice bed on Long Island. He looked at me, sighed, and said, “I’m sorry to be a burden now.” “Stop being so Jewish,” I joked with him. Then I reminded him why I was there. “I am here because you revealed to me and to so many of us the beauty and possibilty of live theatre,” I said. “No one loved playwrights and designers and actors more than you. And I am here because you gave me an extraordinary gift. You saw me. You saw something in me when I was very young and unable to see it myself.

“And I love you,” I told him.

Philip Himberg (he/him) was the artistic director of the Sundance Institute Theatre Program, and is currently the executive director of MacDowell.