It was sometime in the late 1970s when I attended my first show at Long Wharf Theatre.

I was new to New Haven and only knew of the theatre—then just a dozen years old—by its reputation for producing intimate classics, contemporary works, and premieres, several of which—The Shadow Box, The Gin Game—had won Pulitzer Prizes, while others (Streamers, The Changing Room, Ah, Wilderness!) had transferred to Broadway. When I arrived, Long Wharf had just won the Tony Award for outstanding regional theatre, only the fourth time the new honor had been presented.

That first show was Spokesong, an American premiere of a Stewart Parker play with music, staged by Kenneth Frankel, a frequent director at the theatre. I remember John Lithgow riding a bicycle in pursuit of love around that intimate thrust stage, surrounded by actors I would come to know well in the ensuing years: Maria Tucci, John Horton, Joseph Maher, Josef Sommer, Virginia Vestoff. I was enchanted by the play, the music, the performances—and by Long Wharf. I was hooked.

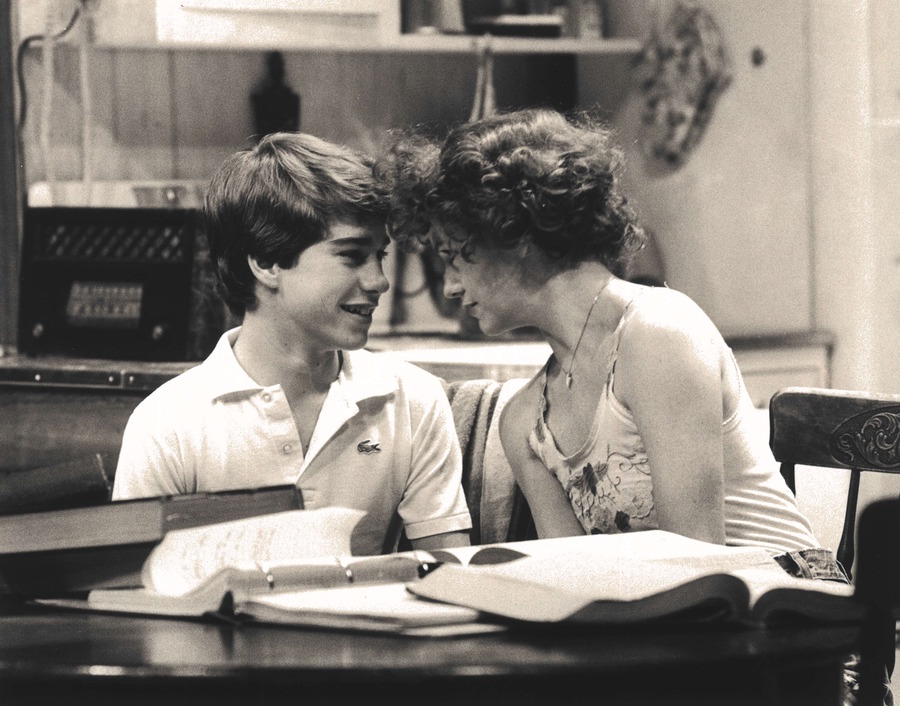

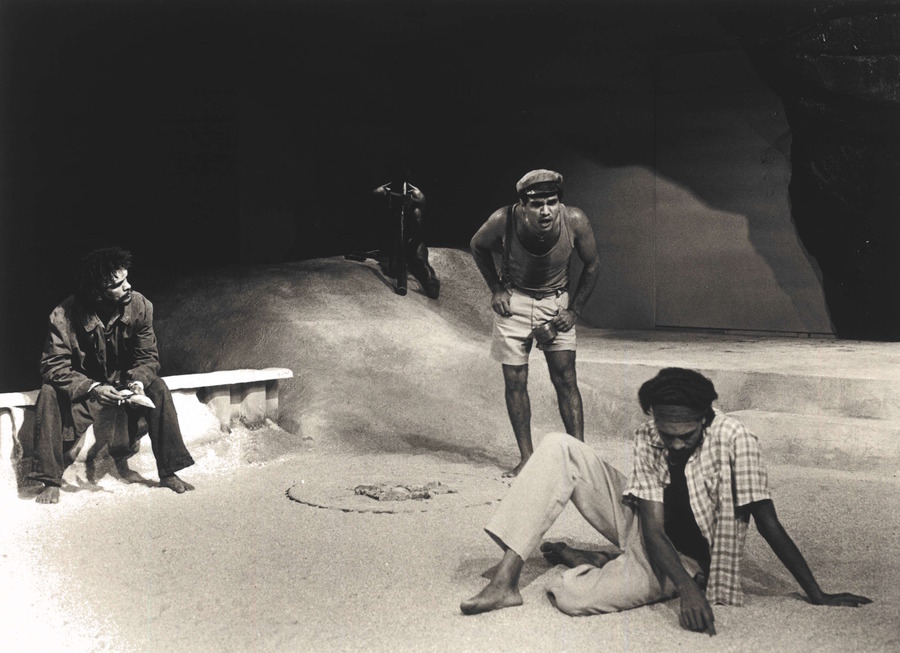

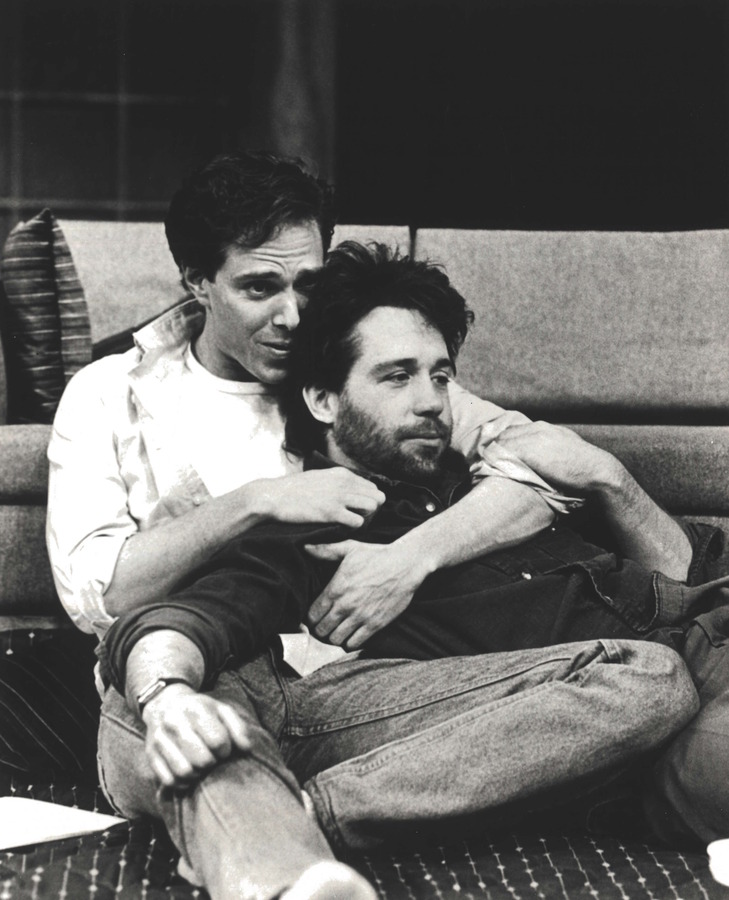

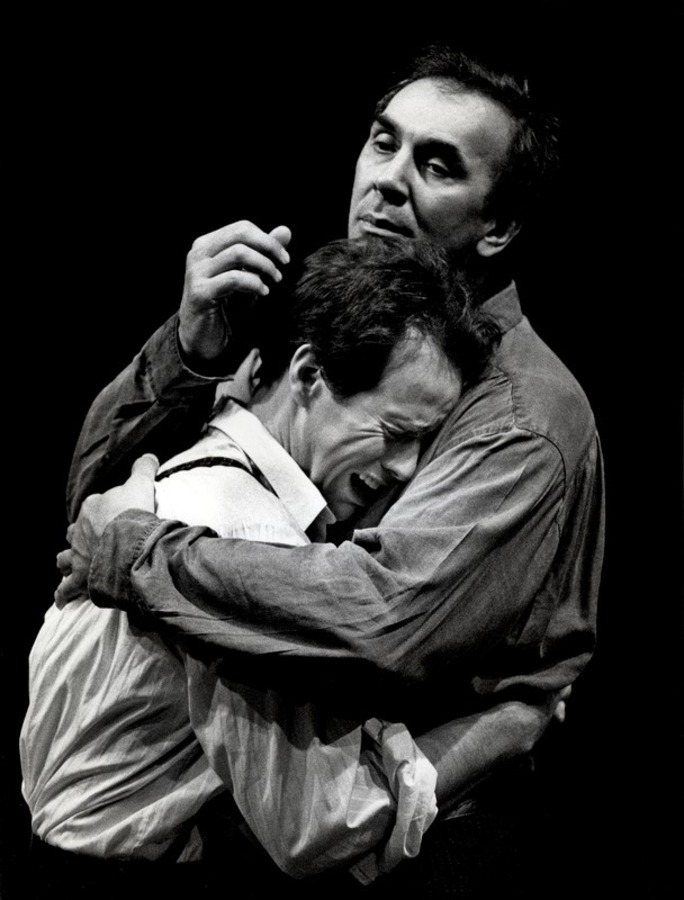

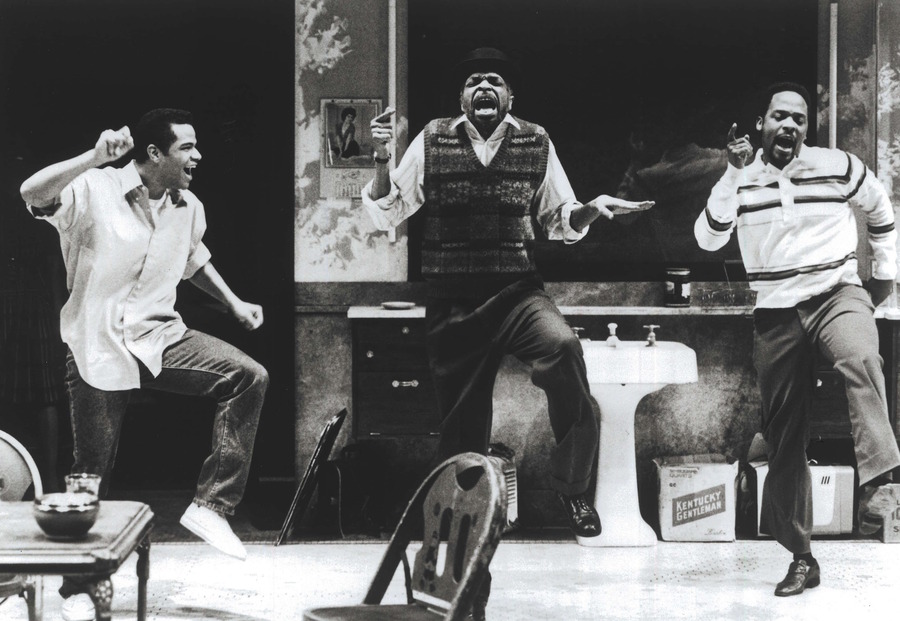

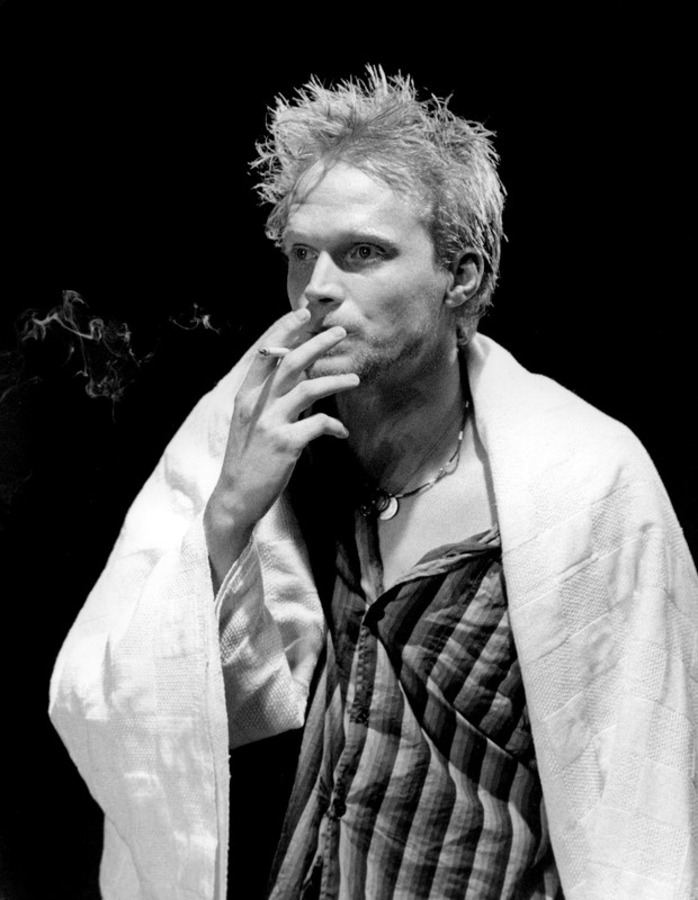

Long Wharf would go on to fulfill its mission and earn its nonprofit status by offering great works from the world stage and plays by new generations of writers. Miller, Williams, Albee, Wilder, and O’Neill led the American giants, while the contemporary Brits included David Storey, Peter Nichols, and Simon Gray. South Africa’s Athol Fugard also found an artistic home there, as did international classics from Shakespeare, Shaw, Moliere, Chekhov, Ibsen, Congreve, Coward, Strindberg, O’Casey, Wilde, Turgenev, D.H. Lawrence, Brecht, and Beckett.

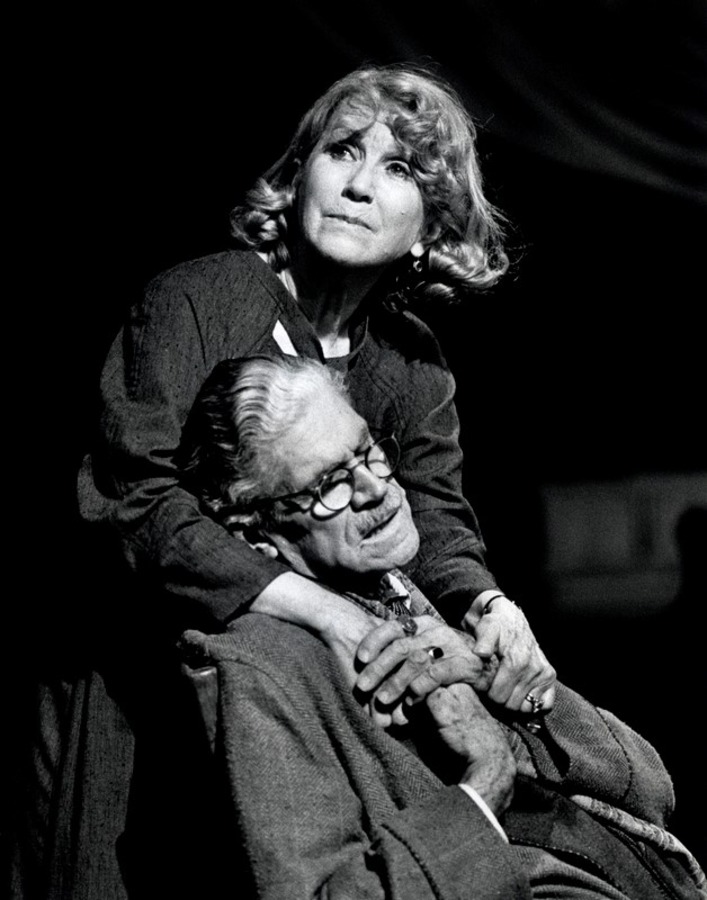

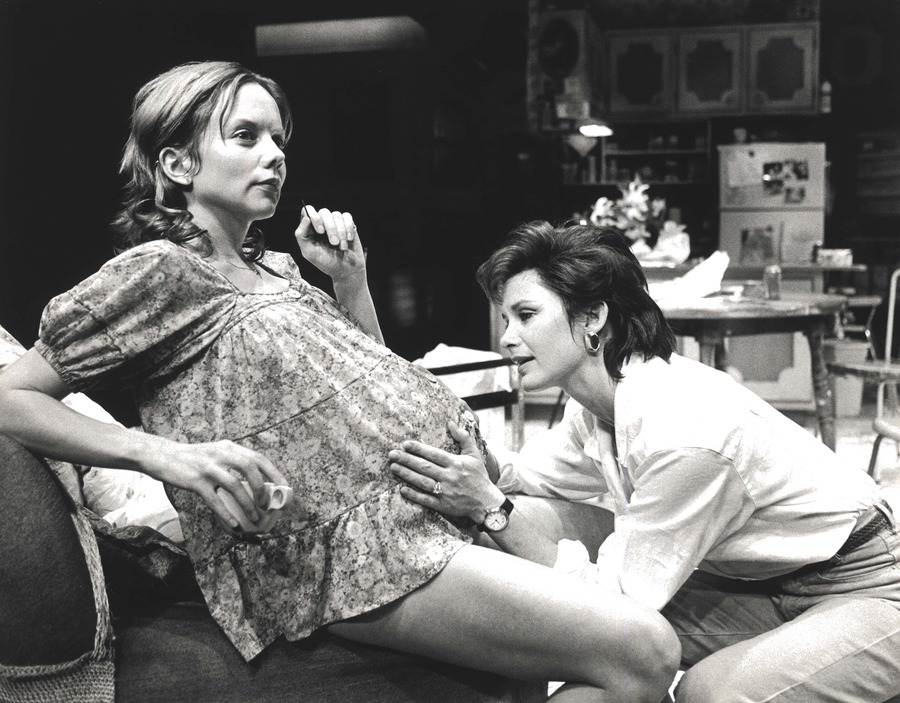

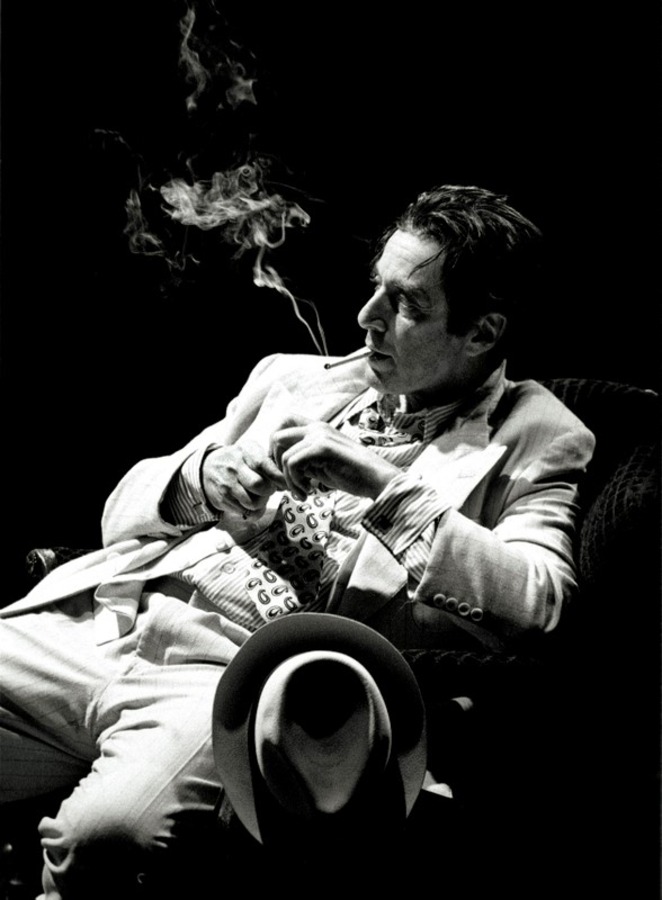

You could always count on amazing acting there too: During those early years I saw John Lithgow, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Lois Smith, Mary Alice, Milo O’Shea, Frank Langella, Julie Harris, Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Tammy Grimes, Colleen Dewhurst, Jason Robards, Frances McDormand, Richard Kiley, Len Cariou, Hal Holbrook, and Nathan Lane, to name just a few. In later years Joanne Woodward, Anna Deavere Smith, Colman Domingo, Martha Plimpton, Dale Orlandersmith, Al Pacino, Martin Landau, Brian Dennehy, Lynn Redgrave, John Douglas Thompson, and countless other masters of the art played the theatre.

So it was a big deal when, earlier this year, it was announced that this storied 57-year-old theatre would leave its longtime home for parts as yet unknown. This fall Long Wharf’s leadership and staff are entering a transitional period of closing up shop, selling off their no-longer-needed inventory of file cabinets and toasters, and placing a half-century of costumes and props in storage. Meanwhile they will continue to plan and fundraise for a future as an itinerant company with a much smaller staff, and an annual budget that will shrink from roughly $5.5-6.5 million to roughly $3.5-4.5 million. After a season of special events and limited-run performances during the fall of 2022 and the spring of 2023, three full productions are planned at various new spaces for the 2023-’24 season.

Though many smaller organizations have made an itinerant production model work for them, Long Wharf may be the first Tony-winning theatre to leave its longtime home for an indefinite nomadic existence. But the financial, artistic, and social exigencies surrounding the move are ones which most not-for-profit theatres anywhere in the U.S. can identify, prompting questions about their own sustainability, mission, and future. At Long Wharf, these questions are live, and the answers are provisional. (You can read here what artistic director Jacob Padrón and managing director Kit Ingui have in store for the theatre.)

Where the Sausage Gets Made

It was one of the most unlikely spots to create a theatre. No grand arts palace or shiny cultural institution designed by a famous architect, it was instead a rented warehouse space at the New Haven Food Terminal, a long, anonymous-looking, one-story industrial complex just off the I-95 highway at the edge of town that housed small manufacturing businesses, including a meatpacking facility. When those businesses’ work was done at the end of the day—sometimes with the faint whiff of sausage still in the air—the large, now-empty, surface parking lot began to be filled with cars of theatregoers arriving for that night’s show with New Haven’s cityscape visible in the distance.

From this funky, no-frills empty space—heavy on concrete and exposed HVAC system—a 487-seat theatre, sans fly space or traps, was fashioned. For me, as a young theatregoer, this bare-bones aesthetic was part of Long Wharf’s appeal. Its focus was clearly on the art, not the architecture; culture, not commerce.

That was the idea of Long Wharf’s founders, by design as well as by necessity. In 1965, the same year President Lyndon B. Johnson signed legislation creating the National Endowment for the Arts, 24-year-old Jon Jory left the Yale School of Drama after his second year, and, with fellow Yalie Harlan Kleiman overseeing the business side, started a theatre with a group of stage-loving backers who were impressed with the pair’s efforts at running a summer theatre season in nearby Clinton.

Long Wharf’s first show was Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (then just 12 years old), followed that first year with works by Euripides, Brendan Behan, Peter Shaffer, Noël Coward, and Anton Chekhov, as well as the musicals Little Mary Sunshine and The Pirates of Penzance.

Those early years were characterized both by exceptional art and financial struggle. After two years and a $35,000 deficit, Jory was fired and was succeeded by Arvin Brown, then associate director of theatre’s childrens’ program. Brown remained for the next 30 years, overseeing many of the theatre’s greatest triumphs, including a steady stream of New York transfers and the premiere of A.R. Gurney’s gift to the nonprofit theatre, Love Letters.

Even Long Wharf’’s misses were thrilling—and the stuff of legend: Tommy Tune and Mike Nichols collaborating on the new musical Double Feature, which didn’t quite work; a sometimes thrilling but short-lived Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? starring Nichols and Elaine May; a challenging Mabou Mines production, The Shorter Shaggy Dog Animation, that occasioned a parade of walk-outs.

“I have such memories of that space,” says Brown, now 82 and living in California. It was when he returned for the theatre’s 50th anniversary in 2015 and “saw all the photos of the productions on the walls, I suddenly realized the impact of the place.”

Shifting Habits and Support

In the ’90s, toward the end the tenure of Brown and his longtime managing director, M. Edgar Rosenblum, the financial pressure of producing a slate of six full productions on the mainstage and three in a 199-seat black box theatre began to mount.

The business model inspired by Danny Newman’s Subscribe Now! in the late ’70s began to show severe signs of strain. Though Long Wharf exceeded 18,000 subscribers in 1986—when Kathleen Turner, whose film career was sizzling, starred in Camille—the numbers started to plummet by the thousands over the next few decades. By the time the pandemic hit in 2020, there were only a few thousand signing up for the full season.

This was in line with national trends, as patrons’ purchasing habits shifted from big-check subscriptions to single-ticket buying as competition has grown for the arts and entertainment dollar. Other income streams also began to dry up, as corporate headquarters moved out of the state, government and foundations’ line items lessened, and, in more recent years, philanthropy from a handful of wealthy donors could not always save the day, as original founders and supporters died or shifted interests.

In 1996, Brown left his position to pursue a career in television. The next chapters of Long Wharf’s life would be characterized both by great triumphs and great catastrophes.

Good work continued to be produced on both its stages under Brown’s successors, Doug Hughes and Gordon Edelstein. But conflicts over the theatre’s future, and a pattern of offstage abuse, would dog Long Wharf for the next two decades.

Over the years, board members were often divided whether or not to relocate the theatre in downtown New Haven, ending its rental status and tenant costs, which included additional millions in capital improvements undertaken by the theatre over the years. There were conflicting cross-currents at play. The theatre’s audience base of subscribers and donors came primarily from the wealthier, and mostly white, suburbs, with only around 10 percent of its audience coming from New Haven proper, whose population was one-third Black, one-third Latinx, and one-third white.

For many patrons, the easy-on/easy-off highway access to the theatre, plus its acre of free surface parking, was a plus, as it meant they wouldn’t have to travel to the inner city, where Yale Repertory Theatre was established shortly after Long Wharf began, largely with support and subsidy from the university. Like many cities, New Haven in the ’70s and ’80s—following a decade of infamous urban “renewal” in the ’50s and early ’60s—was still recovering from an extended period of protests, disinvestment, economic decline, and shifting demographics.

But by the ’90s the fortunes of the city had begun to change, spurred by a new investment partnership between the city and Yale. By the early 2000s, the city was beginning to see a turnaround, with its greatly expanding medical, science, and tech centers, as well as Yale’s own substantial growth with schools and residential colleges. New businesses, shops, and restaurants were springing up. A new train platform brought visitors and commuters into the heart of the city. Some Long Wharf board members accordingly felt the pull to downtown New Haven, and even made elaborate plans for it, but the move would never happen.

But that was the least of the problems the theatre would face in the 21st century.

Checkered Decades

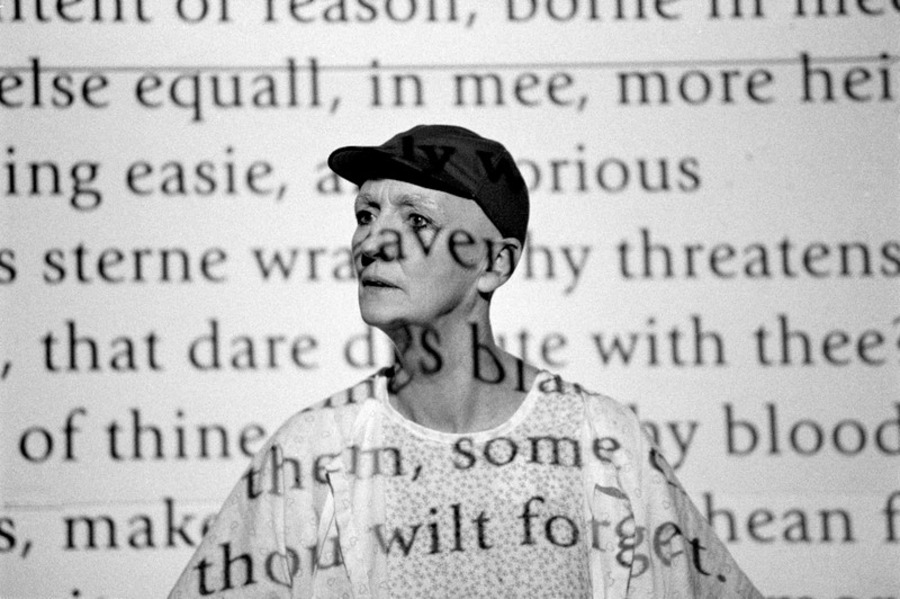

Brown’s successor, Doug Hughes, began his tenure in 1997 with a strong mix of classics (She Stoops to Conquer, Private Lives), contemporary work (new plays by Keith Glover, David Rabe, Douglas Carter Beane), and later musicals and special projects such as Cornerstone Theater’s production of The Good Person of New Haven. He ended his first season with the premiere of Wit starring Kathleen Chalfant, which went on to win a Pulitzer Prize and a New York transfer.

With the subscription slide now showing signs of slowing, generous patronage, and royalties from the ’90s premiere of the unexpected hit I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change, the theatre seemed to be on a steadier financial footing. But conflicts both professional and personal with the theatre’s governance led Hughes to resign in 2001; he has since gone on to have a busy directing career in regional theatre, Off-Broadway, and Broadway.

Hughes was succeeded in 2002 by Gordon Edelstein, who had previously served as the theatre’s associate artistic director. He came in the door just as a city-state proposal was on the table that would have given Long Wharf $30 million to build a new facility downtown (if it could raise a matching number). But the deal fell through, in part due to a change of Connecticut governors and a theatre board that was not unanimously behind the wish to move. Long Wharf would stay on the edge of town.

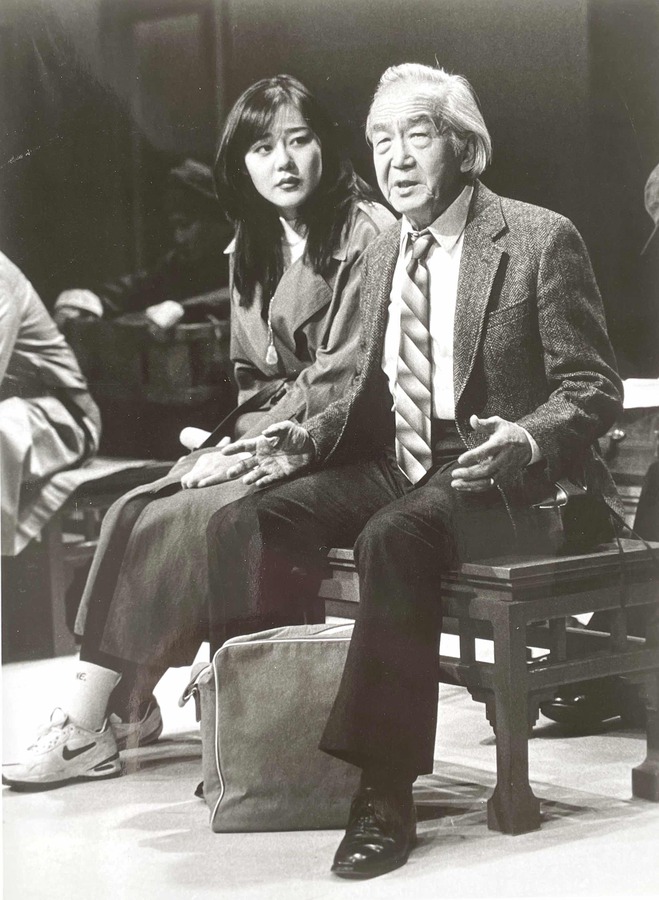

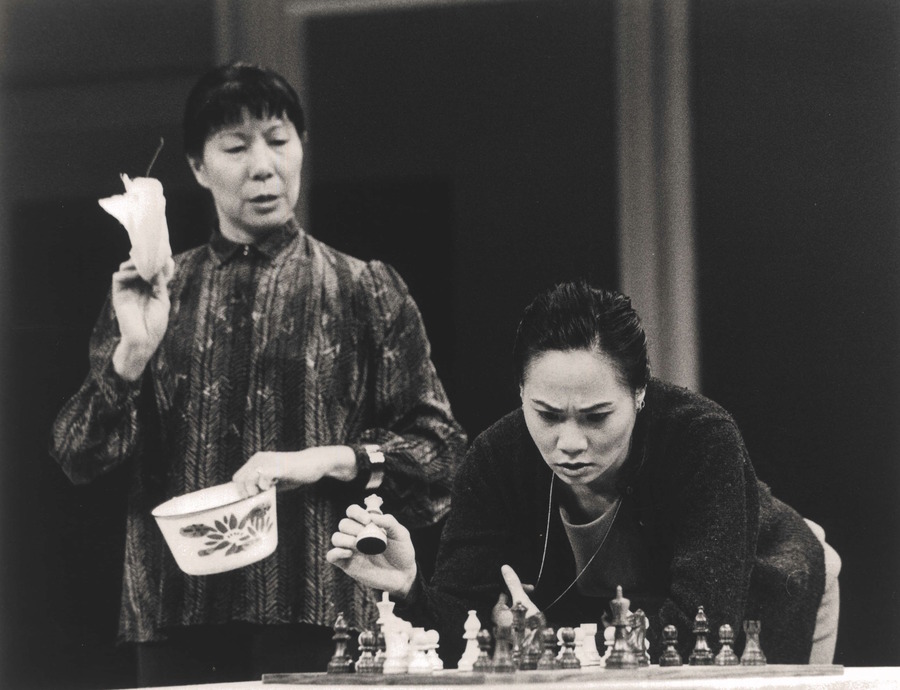

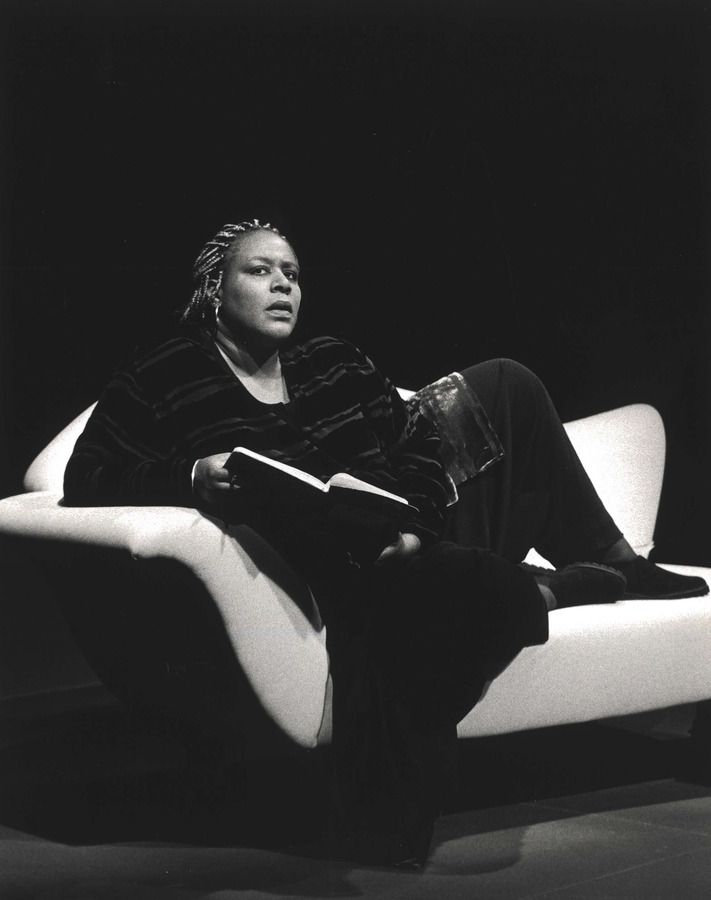

Edelstein’s tenure included premieres by Athol Fugard and new works by Anna Deavere Smith, Samuel D. Hunter, Craig Lucas, Donald Margulies, Dale Orlandersmith, and Paula Vogel, among others; more new and classic musicals fill the two stages, including ones by Charles Aznavour, David Shire, and Gabriel Kahane. Starring roles were filled by such names as Judith Ivey, Mia Farrow, Sam Waterston, and Jane Alexander, and transfers, including Steve Martin’s Meteor Shower and Eliam Kraiem’s Sixteen Wounded, both which later played Broadway.

But behind the scenes, all was not well. The theatre went through series of managing directors—five over 13 years starting in 2006—and an even more dramatic setback came in 2018, when Edelstein was fired after allegations of a pattern of inappropriate physical and verbal behavior toward young women in his employ came to light.

By 2019 the theatre was facing not only this high-profile disgrace but a string of annual deficits, some in the $1 million range. There was $3 million in accumulated debt, covered with a line of credit, and an endowment that hovered around $9 million, about half of what it was at its high-water mark, with remaining funds now largely restricted. The theatre faced a do-or-die dilemma: Come up with a plan and the resources to right and sustain the theatre—or face bringing down the curtain for good.

New Leader, New Vision

The board went in a decidedly different direction with the hiring of Jacob G. Padrón, a Yale School of Drama grad and co-founder of the Sol Project, as the theatre’s next artistic director, making him the state’s first Latinx artistic director, as well as the first artistic leader of Long Wharf who was not a director.

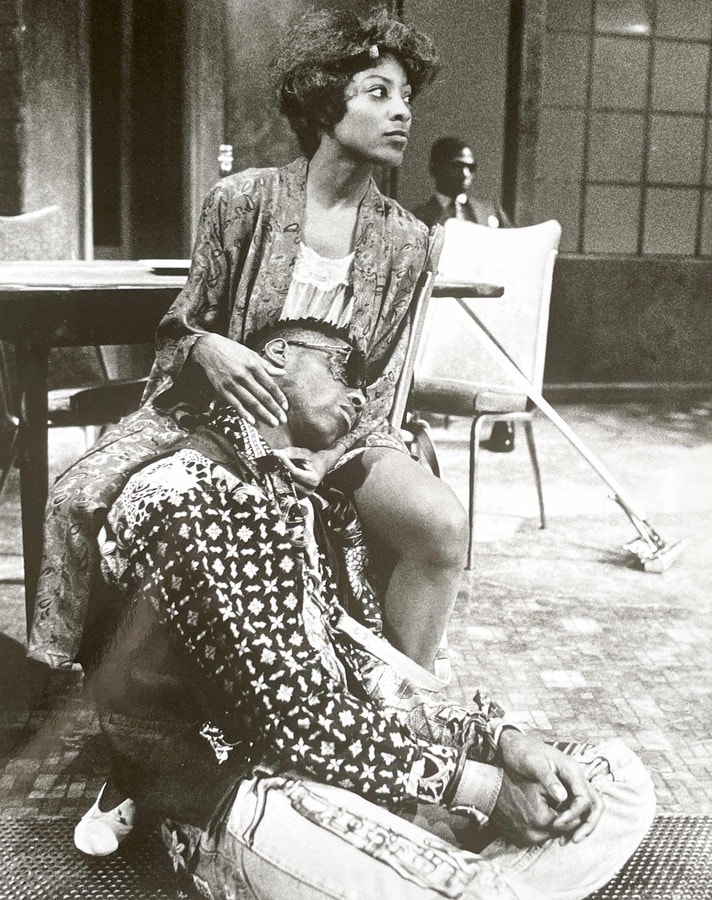

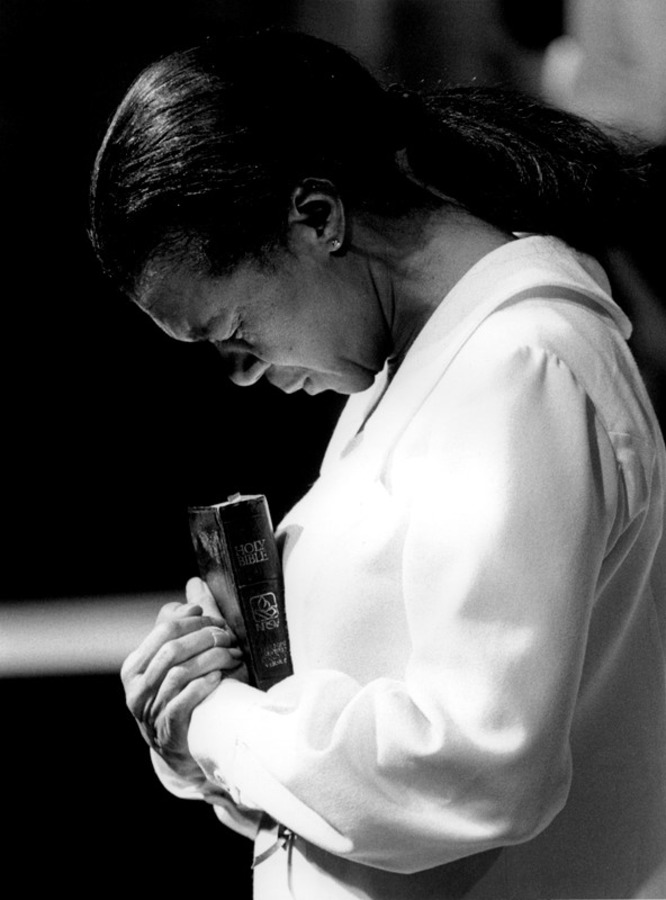

Padrón set out to focus his theatre’s programming on the multicultural city of New Haven, in the belief that by telling these stories the theatre could attract new audiences, most of whom had never been to the theatre, or made to feel welcome there. New funds started to be raised prior to Padrón’s arrival, and the theatre was about to go public with a “Stabilization Initiative”—for which it had already raised $2.3 million—to steady the theatre’s finances and offer resources for Padrón to enact his vision.

But in March 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic intervened, shutting down theatres across the country and scrambling Long Wharf’s short- and long-term plans.

Looming during the pandemic limbo was the theatre’s rental lease agreement with the Food Terminal, which would expire in 2022. It was clear that the facility needed more big-ticket capital improvements, but it wasn’t clear whether the complex would even be there in future years. As New Haven had become an increasingly hot real estate market, there was constant speculation that the Food Terminal might be up for sale.

With the clock ticking and a lingering uncertainty about audience numbers returning to pre-pandemic levels once the theatre reopened, Long Wharf’s leadership opted to double down on Padrón’s vision of connecting more closely with the city itself. This past spring, Long Wharf announced that it would leave its longtime home to become an itinerant theatre. By tapping into money from the stabilization initiative, it is taking the 2022-’23 season off from presenting full productions, using the year instead to move a half century’s worth of the physical material from the complex into storage, including hundreds of seats, lighting grids, equipment, and sound boards. New offices will be set up in New Haven’s downtown arts district, where the largely new Long Wharf staff and its board will plan for the 2023-’24 season—with a significantly smaller budget.

A sense of Padrón’s programming could be gleaned from the few shows that he was able to produce just before and after the shut-down. His first production was Ricardo Pérez González’ On the Grounds of Belonging, and, in the post-pandemic period—when a hesitant audience meant that attendance numbers dropped 70 percent —there was Lloyd Suh’s The Chinese Lady, Eliana Pipes’s Dream House, and Madhuri Shekar’s Queen, all new plays by people of color.

The World We Want to Live In

“What the American theatre is right now,” Padrón said when he first arrived in New Haven in 2019, “is really up for grabs, with cultural institutions asking themselves: What are we doing? How are we doing it? And are we really being of service to our community? The world is on fire, and we have to use art to extinguish it and bring people together. That is our work.”

How will an audience accustomed to a menu strong on Western classics react to the theatre’s broader view, much less its nomadic future? Kit Ingui, the theatre’s new managing director, acknowledges that not all longtime Long Wharf supporters are comfortable with the shift. A look at a Facebook page of the theatre’s fans and alumni shows comments ranging from supportive to critical, which is also reflective of changes in the board. Of the 28 board members listed at the time of Padrón’s first show in the fall of 2019, 12 have remained and 11 new members have joined.

“We acknowledge there are folks right now who are questioning their relationship with the theatre, and there are other folks who are inspired by this new direction,” said Ingui. “This is never about displacement. It’s always about broader and more radical inclusion.”

Ingui said that for many decades Long Wharf, like many other theatres, was sustained by a handful of wealthy donors, which softened the financial impact of declining audiences.

“That’s not the world we’re in anymore, and certainly not the world we want to live in,” she said. “We have utter respect and gratitude to those donors, but we want to be able to survive beyond that—and our old model had not proven that we can continue as we currently produce. So this change has been a long time coming.”

As Ingui looks ahead to productions at different locations—including some site-specific works—she said that Long Wharf will continue with its fledgling membership model, initiated during the pandemic, when live theatrical offerings were no longer available onstage.

The theatre’s leadership insists that they’re not setting out to create a new theatre from scratch, but rather to build on Long Wharf’s legacy. “Though there is a start-up vibe, for sure,” said Ingui, “we’re still Long Wharf Theatre, with a commitment to new work, new voices, and excellent storytelling and performances. Long Wharf Theatre is about the art we are going to make, not the building we make it in.”

A Test for the Field

Could Long Wharf’s transition be an early case study for the field? Teresa Eyring, executive director/CEO of Theatre Communications Group, which publishes American Theatre, said that the pandemic has given theatre leaders pause “to really look at the structures and the assumptions about how theatre is made and how theatres engage with their communities. Long Wharf is a very bold example of a theatre moving in that direction and really trying to reimagine how it exists within its community—and what its economic model is.”

Eyring expects dramatic changes in the field over the next three to five years, as theatres emerge from the pandemic to deal with a changing field artistically, economically, and socially.

“We are in a moment of transition in terms of new generations of theatremakers coming onto the scene who sometimes have really radical ideas about how theatre should exist in our world, our country, and in our community,” Eyring said. “I think what Long Wharf is doing is pretty revolutionary and exciting, and will serve as an example or a model for the rest of the theatre field.”

“When I first arrived,” said Padrón, “I wasn’t contemplating an itinerant theatre. What I was contemplating very deeply was having Long Wharf connect to all of its audiences, and one of the things I was thinking about was that our location wasn’t serving us.”

An old Long Wharf friend is wishing the theatre the best.

“I think the idea of expanding out is very solid,” former artistic director Arvin Brown told me. He confessed that “the idea of doing that without having a central space is difficult to imagine. It’s concerning, but I understand the pressures. I hope for the best. Things are so different now, maybe this is an experiment that will work.”

Brown’s hopeful but anxious words resonate with my own mixed feelings. Revisiting Long Wharf last spring for its final slate of fully produced new plays at the Food Terminal, I found them as fine as any I had seen when I first walked through those doors 45 years ago. They made me curious about the work still to come. Perhaps this is simply the end of a highway off-ramp, not the end of the road. If Long Wharf Theatre in its new configuration can find new and plentiful audiences—a very big if—it just might pave a potential pathway to a new era for other theatres too.

Frank Rizzo (he/him) writes about theatre for Variety, as well as for outlets such as The New York Times, Connecticut Magazine, The Hartford Courant, Encore magazine, and other periodicals and platforms, including ShowRiz.com. Twitter: @ShowRiz.