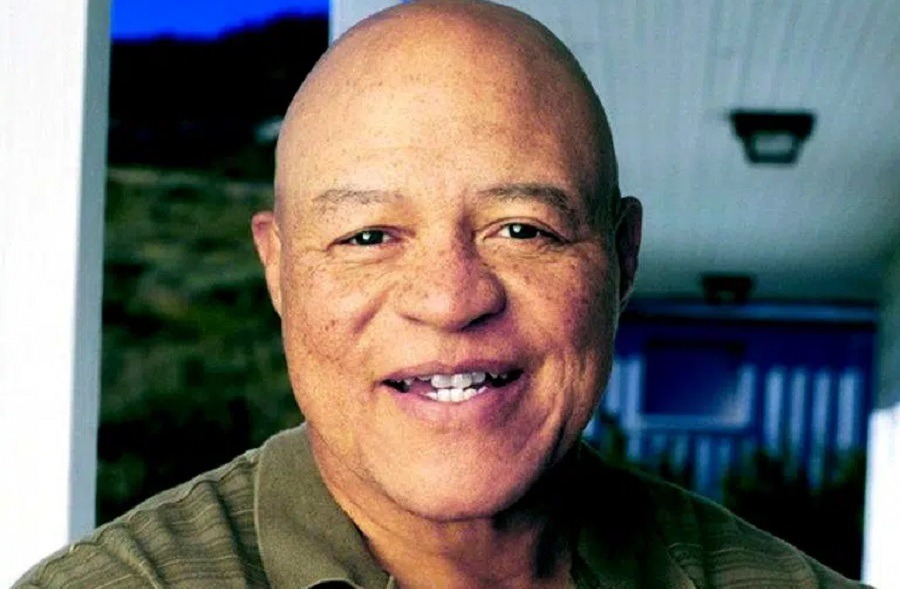

Veteran stage-and-screen actor John Beasley is grateful to finally be on a Broadway-bound track at age 79, after decades of regional theatre, feature film, television movie, and episodic TV credits. It’s happening with the musical adaptation of The Notebook, whose world premiere run at Chicago Shakespeare Theater just began performances and runs through Oct. 16. The new musical, with songs by Ingrid Michelson and book by Bekah Brunstetter, is drawn from the 1996 best-selling novel by Nicholas Sparks that spawned a 2004 hit movie starring James Garner, Gena Rowlands, Ryan Gosling, and Rachel McAdams; Beasley is in the role Garner played, an older version of one of the story’s young lovers. Sparks, the writer behind the show’s source material, is an Omaha, Neb., native, as is Beasley.

By the time The Notebook makes it to New York next year Beasley will be 80, a ripe age for this seasoned character actor to reach that milestone. While he may not be the oldest actor to ever debut there, he will be among a small group of octogenarians to do so. Given that he got his professional acting start at 45, Beasley said, “That Broadway comes at this age—I guess that’s par for my course. I think it’s the ultimate validation of my acting career. Broadway’s always been that vision. I’m told it’s life-changing.”

Excited though he is, Beasley’s keeping it all in perspective.

“To be a working artist is the highest calling, and I appreciate wherever it takes me,” he said in an interview over the summer. “If I never got to Broadway, I would still feel I’ve had a pretty successful career.”

He stars as Noah opposite Tony winner Maryann Plunkett as Allie; his younger selves are played at various ages by John Cardoza and Ryan Vasquez, while Plunkett’s are assayed by Jordan Tyson and Joy Woods. The chance to create a stage role is a particular highlight, he said.

“Normally you’re cast in a play that has legs and it’s set, but to be able to create this character in a world premiere production is special,” he said. “It’s new material; it’s good material. You think there are pieces that are written for you, and that’s how I feel about playing Noah. I was told a long time ago that when a part is yours, 100 good men can’t stand in your way.”

In fact, he was preparing to do a play at Indiana Repertory Theatre when he found himself in the running for The Notebook. He had submitted a well received rehearsal video many months before but heard nothing back; it turned out it wasn’t a lack of interest on the part of the producers but a pandemic delay.

It came down to him and one other contender for the role. When the other actor dropped out, though, Beasley still had to read for the team. He flew with his wife to New York; while he had only been provided with sides for his scenes before, he had the entire script. He waited until the flight to read it, not wanting to get his hopes up too high.

“I said to Judy, ‘I know this is Broadway, but at this point in my career I’m looking for good material.’ It wasn’t about the money. It wasn’t even about Broadway. I was prepared to turn it down if the script was not as good as the script I was going to do in Indianapolis. I finally read it on the plane, and by the time we landed in New York I was sobbing. My wife handed me a tissue and I told her, ‘I’ve gotta do this. If I get in that room, it’s mine.’ I told that story to the cast here and they said, ‘And it is.’”

For years Beasley made a career playing characters older than himself, from Willy Loman in an Omaha Center Stage production of Death of a Salesman to Hoke Colburn in an Omaha Community Playhouse mounting of Driving Miss Daisy to Brother C. Charles Blackwell in the Robert Duvall film The Apostle. With Noah, he has the chance to play a character his own age, and someone whose life circumstances cut close to home. Even as Noah and Allie face mortality, their love burns bright; when she develops dementia, he moves into her nursing home so that each day he can read her the story of their lives together, thus transcending time.

“I know this guy,” said Beasley. “I can identify with this guy. I’m at a point in life where I’m burying friends now all the time, so I can relate to it. I can play to his life experience. I’ve been married 57 years. I can put myself in the place of this guy and imagine what if this were me and my wife—how would I react.”

He has taken some pains not to be influenced by previous iterations of the story.

“I haven’t read the novel. I did see part of the movie; it’s a real tearjerker. But I didn’t want to look at it and try to do some of the same things James Garner did. This is me creating a role, and I want to do that on my own.”

The actor is especially delighted to be paired with the consummate Plunkett, whose Broadway work spans Sunday in the Park With George, Me and My Girl, The Crucible, The Seagull, Saint Joan, and A Man for All Seasons. She’s also appeared in the entire 12-play cycle of Richard Nelson’s epic “Rhineback Panorama.” Beasley and Plunkett, strangers to each other’s work before The Notebook, clicked before ever meeting in person.

“Maryann and I knew we had a connection even over our Zoom workshops earlier in the year,” said Beasley. (But for a COVID surge, the production was meant to have begun rehearsals in February.) “It’s a connection you have to make. It’s a trust you have with each other and you can find that trust early on, and we did.”

An Omaha native, Beasley developed a love for theatre in his youth, though he get sidetracked by his participation in athletics and activism. He found even less time for stage work after he and Judy started a family. The couple’s two adult children, Tyrone and Michael, are both actors.

As a young man caught up in the Civil Rights protests of the 1960s, Beasley was a vocal critic of abusive law enforcement practices. Upon receiving death threats, he promptly moved his family to Philadelphia, where his wife is originally from, in 1968. Working a series of jobs there to provide for his family, from jitney driver to janitor to longshoreman to machine operator to clerk, he still dabbled in theatre, acting in his first Shakespeare production at the Germantown Theatre Guild in Philly.

When he felt it was safe for him and his family to return to his hometown in the early 1970s, he began drama studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The folks he trained with there, among them Royal Shakespeare Company veteran David Suchet, encouraged his talent. When Suchet returned as a guest director, he cast Beasley as Mitch in a UNO theatre staging of A Streetcar Named Desire.

Steeled by faith and confidence, Beasley balanced life as a laborer and family man with roles at local theatres and in industrial films, secure in the belief that if he honed his craft it was only a matter of time before he would find breakout success.

“I knew those things would come, even when I was in college,” he recalled. “I dropped out early because I didn’t feel I really needed a college degree to pursue what I wanted to do in life. Bottom line, I worked.”

ln Omaha, he broke casting barriers by winning roles not traditionally given to actors of color. He then tested his wings outside his hometown, earning parts at regional theatres such as the Mixed Blood in Minneapolis, the Goodman in Chicago, and the Alliance in Atlanta.

Along the way he became a stock player in major productions of August Wilson plays, culminating in roles at the Huntington Theatre in Boston and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In 1993, the Goodman put up a fresh-from-Broadway production of Two Trains Running that included some of the original cast. He joined the ensemble for their Chicago stop on the way to the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles. It was at the Goodman that he caught the attention of a holdover member of the Broadway cast, the inimitable Roscoe Lee Brown, who was unfamiliar with Beasley or his work.

Beasley fondly recalled Brown.

“After he saw me in a rehearsal he asked around about me and came to me and said, ‘I understand you started late, but you’ve got plenty of time and you’re going to do well,'” he said. “I needed that at that time, because I was in my middle 40s and people were telling me to give up this dream—that it had passed me by.”

Chicago’s been good to Beasley. His work at the Goodman led to other regional theatre gigs as well as screen work, including Brewster Place with Oprah Winfrey and the project he describes as having “changed my life,” The Apostle, a passion project of its actor-writer-director, Robert Duvall. Aware that Duvall was seeking naturalistic actors, Beasley figured his “reputation for doing real people” gave him an edge in casting.

“I had just finished playing Hoke Colburn in Driving Miss Daisy when I read the part of Brother C. Charles Blackwell in The Apostle, and I thought, well, that’s Hoke Colburn when he’s not driving Miss Daisy,” Beasley said. “I had already developed the Southern accent and the old man’s gait to make it believable in front of a live audience. I worked a lot of that character out in the theatre, so when I did get The Apostle, I already had the guy down.”

That led to series regular work on TV’s Everwood and The Soul Man starring Cedric the Entertainer, and recurring roles on such shows as CSI, Judging Amy, and Treme. He’s also a familiar face from feature films (The Mighty Ducks, Rudy, Losing Isaiah, The General’s Daughter, Crazy in Alabama, The Sum of All Fears) and TV movies (To Sir with Love II, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks).

Along the way he founded and ran his own stage company, the John Beasley Theatre & Workshop, in Omaha, where he produced August Wilson’s entire 10-play cycle, bringing in guest stars and fellow Wilson repertory players Anthony Chisholm and Willis Burks for a production of Jitney.

During a slowdown few years ago, Beasley realized it had been years since he last worked in Chicago, so he decided to list with an agency there. The decision paid off when the agency sent him up for The Notebook.

“You know, I would probably not have gotten called on it if it wasn’t for Chicago.”

And he might not be ready for the role at all if it weren’t for the attention he paid to his home life.

“We were going through some ups and downs early in our relationship, my wife and I,” Beasley confessed. “There were things to work through—and we did. I felt it would be better for me to stay here with my wife and family. It turned out to be the best decision I made. Judy and I have been together for most of our lives now.”

Between his “life experience” and theatre chops, he was ready when The Notebook called. “I’ve paid my dues, and I know that,” he said. “The foundation was already set.”

The creative apple doesn’t fall far from this solid oak tree of a man. His son, Tyrone Beasley, appeared in a production of The Merchant of Venice directed by Peter Sellars at his father’s old stomping grounds, the Goodman. It co-starred Philip Seymour Hoffman and John Ortiz, and went on to New York and Europe.

Tyrone also served as artistic director of his father’s theatre, sometimes sharing the stage with him. Earlier this summer Tyrone, now artistic director of Nebraska Shakespeare, recruited his father to portray Prospero in a Shakespeare-on-the-Green version of The Tempest.

Indeed, though screen work has afforded him a comfortable living (and he’s still hoping to realize the dream of film about his late friend, football star Marlin Briscoe), the stage remains John Beasley’s true acting home. He hopes to revisit a one-man Paul Robeson show he did years earlier because he’s now aged into the part. But for the time being, Noah in The Notebook is his one true thing, and perhaps the beginning of a new chapter in this thespian’s epic saga.

“This could possibly be the role of my lifetime.”

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance writer and the author of the 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.