When I edited theatre reviews at Back Stage West in the fall of 2001—i.e., in the immediate aftermath of 9/11—it seemed that, no matter the show they were covering, critics would either say something like, “This frothy laugh riot is exactly the kind of thing we need right now to take our minds off the state of the world,” or, on the other hand, “This hard-hitting drama is exactly the kind of gritty challenge we go to the theatre for in times of trouble.”

My takeaway: Maybe we need a little of both, only moreso when we’re in a moment of collective social trauma. (At the time I singled out the way a performance of “Pirate Jenny” by the great Melody Butui, in a Brecht-Weill revue at L.A.’s Odyssey Theatre, sounded freshly unsettling while the World Trade Center still smoldered.)

For myself, I can’t pretend I’m above either populist comfort food or snob hits, either so-called guilty pleasure or virtue-signaling significance. I had as fine a night at the theatre at Six as I did at Pass Over, and I think I’m fairly typical. As I watch the show listings pour in for the 2022-23 season all across the U.S., I see theatres of all sizes scheduling musical revues and murder mysteries (don’t be surprised if Sandy Rustin’s newish stage version of Clue is among the most-produced shows of the coming season—you heard it here first), but also no shortage of meaty contemporary dramas and thorny classics.

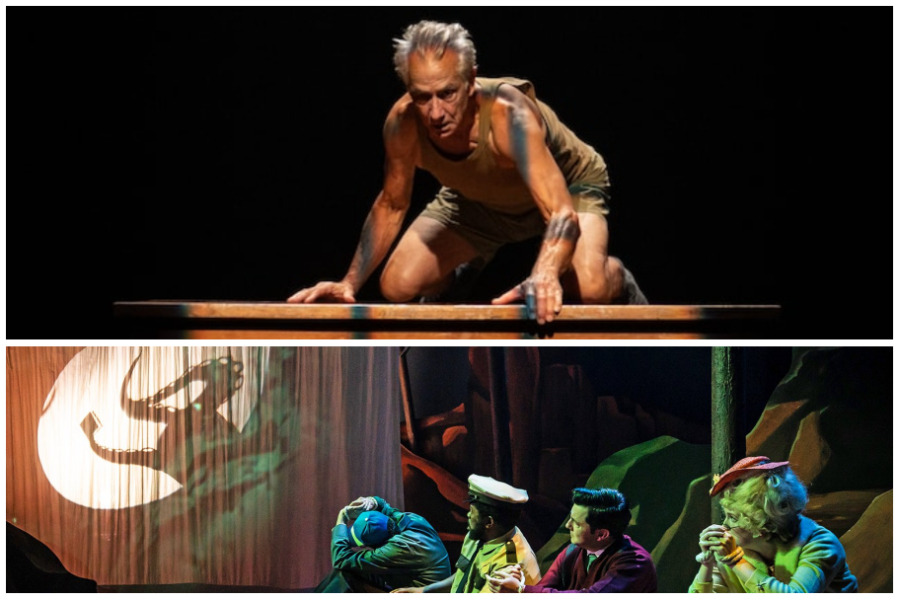

A quartet of current shows stood out to me as instructive illustrations of the sharp contrasts between unapologetic escapism and what we might call no-exit theatre, between candy and protein. All are ambitious in their own disparate ways, and all four are shows I would happily attend if geography were no obstacle (as it is, there’s only one I’ll likely be able to catch). At one pole, more or less, are two new musicals: an adaptation of the 1950s sci-fi film It Came From Outer Space, now running at Arkansas’s TheatreSquared through Sept. 18, and The Griswolds’ Broadway Vacation, which is exactly what it sounds like—a new musical based on the National Lampoon Vacation franchise, but with a theatre-centric twist—at Seattle’s 5th Avenue Theatre, Sept. 13-Oct. 2. The other two examples are worthy projects of entirely different kinds: director Bart DeLorenzo’s revival of Ibsen’s harrowing Ghosts, at the Odyssey Theatre through Oct. 23, and Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski, a solo show in which the flinty, soulful actor David Strathairn plays a real-life Polish witness of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Holocaust, Sept. 10-Oct. 9 at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience (and probably at a theatre or screen near you soon). To paraphrase the old Sesame Street song: Each of these things is not like the other.

It Came From Outer Space, it turns out, has slightly weightier ambitions than might at first seem obvious. (In fact, both this show and Remember This played previously at Chicago Shakespeare Theater, clearly a tastemaker in many flavors.) As its creators, Kellen Blair and Joe Kinosian—who created a durable regional hit a few years back with the frothy mystery musical Murder for Two—pointed out by email, the original black-and-white film is a cut above the likes of Plan 9 From Outer Space, “although we probably do have those kinds of movies to thank for the tropes of vintage sci-fi being so familiar to audiences.”

A bigger selling point for the show, they say, is that the original script was by Ray Bradbury, which means that beneath its tale of jellyfish-like, shape-shifting extraterrestrials crash-landing in the Arizona desert is a Cold War-era allegory of intolerance and conformity with plenty to say to our current American moment. “The ideas and themes Bradbury was playing around with are timeless and universal,” wrote Blair and Kinosian. “At its core, it’s not really about aliens.” Nor is the show intended chiefly as a parody. “There’s a lot of silliness in the script, because that’s just who we are as writers, but we certainly aren’t ridiculing the movie, or even the genre,” they wrote. “It Came From Outer Space was Universal’s first 3-D film, and we were much more interested in capturing that spirit of invention, playfulness, surprise.”

What’s more 3-D than theatre, after all? Blair and Kinosian said that their relationship with Chicago Shakes, which in turn has something of a working relationship with Universal Theatre Group, helped grease the wheels of this stage adaptation. Likewise Warner Brothers, which owns the rights to the Griswold Vacation property, granted authors David Rossmer and Steve Rosen (The Other Josh Cohen) dibs on musicalizing the iconic road trippers created in the original 1983 film by Chevy Chase and Beverly D’Angelo.

“As far as we know, we’re the first to be given the honor of bringing the Griswolds to the stage—no pressure, ha,” Rossmer and Rosen wrote to me by email. True to its source material, the show, unlike Outer Space, is entirely intended as parody, or what its authors call “a comic and relatable look at that glorious monster that is a family vacation,” only in this case, both the Big Apple and its precarious tourist trade are targets as well. If you’re prone to gag a little at the show’s high-concept premise, not to worry—its authors are one step ahead of you. When I asked which specific Broadway shows the duo plan to, ahem, lampoon, they replied: “Ironically, we parody the trend of adapting films into Broadway musicals…so basically, we’re making fun of ourselves.” Rossmer and Rosen promised both “plenty of Easter eggs” for musical theatre nerds, while also claiming that Griswolds’ Broadway Vacation is “very much a musical for people who normally don’t like musicals.”

As someone whose office (when I go to it) is in midtown, and who regularly attends shows on Broadway and in the vicinity, I’ve braved my share of tourist hordes—and I couldn’t be happier to see them increasingly returning, after the bleak plague years we’ve just been through. I wondered how much the fraught topic of COVID restrictions (and the equally fraught issue of their relaxation) might play into the Griswolds’ theatregoing experience, and Rossmer and Rosen demurred, saying they’re “aiming for something a little more timeless. We’ve been through enough. It is our hope that this show will help to wash away some of the collective trauma we’ve all experienced over the past few years. After all that, every single one of us really, really deserves a vacation.”

Family dysfunction is no joke in Ibsen’s Ghosts, and the only escapes on offer are shameful compromise and assisted suicide. This was arguably the play that set the template for a great deal of Western drama ever since; every time you see a drama or a teleplay in which a terrible shared secret or disgrace is slowly, then shatteringly revealed, you’re being haunted by this seminal social tragedy about a well-meaning widow and the men who’ve ruined her life.

“This is the play where the woman didn’t leave the house,” said DeLorenzo, the director, referring to the assertive exit of the heroine in Ibsen’s previous play, the more famous and more beloved A Doll’s House. While Nora Helmer’s door slam provided a cathartic and galvanizing jolt, the decision of Ghosts’ Helen Alving to stick around “was probably more true and realistic to the time, as most women didn’t leave their husbands but tried to make it work.”

The play is thus necessarily grimmer, as Ms. Alving (played by Pamela J. Gray in the Odyssey production) reckons with the full consequences of a corrupt marriage. It is also more pointed than its predecessor—not only because, as DeLorenzo put it, Ibsen essentially set out to plant the Olympian stakes of a Greek play in a contemporary domestic context, but because, with the play’s brutal finale, Ibsen went full Greek.

“The ending is one of the greatest and most difficult scenes in drama to endure,” DeLorenzo conceded of the long scene in which Alving agrees to euthanize her adult son, Oswald, if he suffers another attack from the syphilis her late husband bequeathed him—only to watch as he begins to succumb to an attack. All eyes are on Alving and her fateful choice; and curtain.

“There’s something interesting about a playwright making a gratuitous gesture,” he noted. The play could have ended with all the secrets revealed and relationships ruptured, DeLorenzo pointed out, and it “would be a good play without that last scene.” It’s something that comes up when he teaches his CalArts theatre students King Lear: “Why does Shakespeare kill Cordelia? Everything has been resolved. Why this extra note of bleakness? You don’t need it for the plot; the playwright wants to say something more, and to put us through the wringer. We don’t need it—or maybe we do.”

There is nothing gratuitous about the events that inspired Remember This, of course, but the question of what dramatic gestures on the part of theatremakers might be appropriate or not is especially fraught, as this is a work of art endeavoring to convey the horror of the Holocaust, and, not incidentally, to trace the signs of incipient fascism and indifference to atrocity in our own time. The play features David Strathairn—the flinty, soulful actor who, coincidentally enough, recently played Rev. Manders in Carey Perloff’s revival of Ghosts at Seattle Rep—as Jan Karski, a Polish diplomat who bore witness and tried in vain to warn the Allied powers, up to and including President Roosevelt, about the genocide transpiring in his home country before and during World War II, then spent his remaining years haunted by his inability to save lives, until he unburdened himself to French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann in the landmark 1985 Holocaust documentary Shoah.

Strathairn saw that film when it came out, and recalled to me, “I walked out of the Thalia Theatre and was in a daze for a couple of days about the whole thing.” So when Derek Goldman, founder of Georgetown University’s Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics, approached Strathairn nearly 10 years ago about working on a project about Karski, the actor immediately sparked to the idea, and to the Lab’s stated mission to “humanize global politics through the power of performance.”

“The best way to change the political or intellectual consciousness of a person is through the gut, through our emotive pathways,” Strathairn told me last week, adding that the response to the play so far, in previous runs at Chicago Shakes and at D.C.’s Shakespeare Theatre Company, has shown that the live exchange of theatre is indeed suited to this task. “We have found that the experience of witnessing the story of this man’s life and what he did in a theatrical space has a palpable effect on the audience, in a very emotive, visceral way. It’s a live, personal confrontation with the material.”

While busy with a film and TV career, Strathairn has done his share of stage acting over the years, mostly at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater. Remember This is something else for him, though. As Strathairn put it, “I never really saw this as a so-called transactional event, where it’s in a theatre just for the sake of having a play. Although it’s an interesting play, our intention was always to give it a curricular application.”

For his part, Goldman—who created the play in collaboration with Clark Young and Strathairn—wrote in an email that “metaphorically, but also in some very immediate way, we the audience are cast as Karski’s students…This does not mean the play needs to be didactic.” Instead, he said, the creators are “committed to an experience that is very deeply embodied, physical, expressionistic, in ways that most classroom experiences are not.”

The question of emotional engagement with the unthinkable is in fact a key theme and thread in Remember This, as Karski, a Gentile, recounts trying to turn himself into a kind of human camera, a “machine,” as he recognized the severity of what he was witnessing, first in the Warsaw Ghetto, and later at the Auschwitz extermination camp, and felt his terrible responsibility to report it clearly and lucidly.

“Anybody who has had an experience that they may not be able to reckon with or articulate—it’s in their body,” said Strathairn. All the better, then, that it comes to us embodied by an actor of such depth and acuity. But the tragedy, both of Karski’s experience and our own, is that truths that don’t live in our bodies, or that we can be made to feel as if they do, can be a hard sell. In one memorable scene, Karski recalls his visit with Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1940s, who listened politely to Karski’s testimony about what he saw in Poland before replying with a curious but all too common species of disbelief. “He told Karski, ‘I don’t believe you,” Strathairn said. “’I don’t say that you’re lying. But I don’t believe that this is possible.’”

If it seems especially unsettling that such straightforward testimony could be so denied, consider the truthy times in which we live.

“For us this is not a history play but very much a current events play,” wrote Goldman. “We find that the contemporary application of the events and themes of this play are bottomless, and get more and more vivid.” The current war in Ukraine, and the pivotal role of Poland in the same vicinity, albeit a different context, obviously comes to mind. But more broadly, Goldman said, “The play speaks deeply to the issue of the status of truth and the danger of disinformation and denial.”

The question remains: What do we want from the theatre? Fiction that feels like truth? Truth rendered in the digestible form of fantasy? Both, or neither? Strathairn told me that Seattle audiences seemed so happy to be back in the theatre that they initially greeted Ghosts with eager laughter, “as if it was some kind of Seinfeld episode,” only to grow quiet as Ibsen’s play twisted the knife. Said DeLorenzo, “I do like an amusing play. But I think we always need plays which ask fundamental questions about civilization. It’s the theatre’s most important purpose, going back to the Greeks.”

To which I would only add that, for me, a spoonful Plautus helps the Euripides go down.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org