Driving north from Chicago on I-94, you’ll pass Touhy Avenue, Dempster Avenue, and then just off the freeway on your right will appear a high school campus. From the outside, it doesn’t appear strikingly different from any of the other suburban high schools littered around the Chicagoland area: just a collection of beige, square buildings abutting one another, with decent athletic facilities, all set against the backdrop of the large Westfield shopping mall. This is Niles North High School in Skokie, Ill. One half of Niles Township High School District 219, a traditionally middle-class community, the high school serves approximately 2,200 students from a wide variety of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. More than 40 first languages are spoken in students’ homes, and only 38 percent of students identify as white.

While this vibrant community has always placed a strong emphasis on arts education, the past 29 years of artistry at Niles North have been nothing short of a miracle. The magic comes courtesy of a spectacular theatre program led by Timothy Ortmann, who will retire this year from his longtime post as the high school’s theatre director and the fine arts director for the district. Many would credit Ortmann with the creation of one of the most ambitious high school theatre departments in America; it’s certainly the only one that has hosted Kabuki master Shozo Sato, not once but three times as a guest artist and director.

In Skokie, and to some extent across Illinois, Niles North Theatre has become synonymous with the kind of theatrical excellence you have to see to believe. The department and Ortmann have received many honors, and program alumni have gone on to very successful careers in every corner of the entertainment business. Among countless performers, designers, and technicians, they include actors Jonathan Kite (2 Broke Girls) and Clara Wong (Billions); comedian Esther Povitsky (Crazy Ex-Girlfriend); producers Stephen Feder (T-Street) and Tyrone Phillips (Definition Theatre Company); and artist-professors Mason Rosenthal (Virginia Tech) and Kristy Leigh Hall (University of South Carolina).

This track record would come as no surprise to anyone acquainted with the full slate of collegiate-level courses Ortmann developed over the last 29 years. Prior to becoming the district’s fine arts director, Ortmann taught five classes during the school day and directed after-school rehearsals. In addition to the introductory Theatre Workshop course, the department offered an Advanced Theatre Studio class with changing curricula each semester, including subjects such as mask work, monologue analysis, or animal work. Ortmann has even offered a theatre class specifically for students with disabilities. The program’s further class offerings focused on acting, directing, production, stagecraft, and a summer Shakespeare intensive, wherein students routinely dedicated weeks of their summer vacation to First Folio analysis, stage combat training, and studying film adaptations.

All of this opportunity and careful study ultimately contributed to the program’s true miracle: the creation of a quasi-professional, constantly replenishing repertory company with a full-scale mainstage and second stage season, performing sophisticated material like Marvin’s Room, A Chorus Line, The Zoo Story, On Stars Not Falling, Kabuki Medea, K2, Equus, Hapgood, Falsettoland, Chicago, Clybourne Park, and Punk Rock with 14- to 18-year-old artists. The Niles North Theatre became so well-regarded in the community that they were able to sell season subscriptions, and not just to the parents.

Instrumental in this success, or perhaps justified by it, has been the financial support of the district. Jerry Proffit, who preceded Ortmann in his role, told me that when he once went to the arts department chair with the news that he was $2,000 over budget, the chair reportedly said, “Don’t worry about it.” Ortmann successfully harnessed the community’s support to motivate the district to continue investing in its arts programs. By the time the district received the Kennedy Center Award for Best Fine Arts Program in the Nation in 2007, the committed tax base in Skokie, Lincolnwood, Morton Grove, and Niles meant that the school was devoting over 4.53 percent of its total instructional budget to the arts, equating to more than $2 million annually. A sizable portion of that money supported the exemplary work of the Niles North Theatre Department, allowing students the opportunity to work with up-to-date lighting equipment, as well as having a dedicated scene shop and costume shop. They also have mention a state-of-the-art black box theatre, complete with a tension grid for unmatched flexibility in lighting design.

Other keys to the program’s success have been its emphasis on community-building and mentorship. Ortmann went to Niles North himself before attending conservatory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, then going on to work in Chicago theatre professionally. Jerry Proffit, who started the notably ambitious theatre program at Niles North, reached out to Ortmann in the early ’90s to see if he’d like to come and direct at his alma mater. His first play was Crimes of the Heart, and Proffit said it was immediately clear that Ortmann “was a better director than I was.” Ortmann had a special gift for directing, he noted, especially with students. “He was good about evoking a response from the student by making an observation about them. He would ask, ‘What is the character thinking right now? What are you thinking right now?’ You could see him getting the actors onstage working harder, and they felt free and comfortable with him experimenting; they didn’t feel frustrated or self-conscious,” Proffit explained.

When it was time for Proffit to retire, he asked Ortmann if he’d consider taking over. Proffit recalled that Ortmann was already thinking big at his job interview: When asked what he would change in the program, Ortmann replied that he’d like to do a “director’s choice” show during the first week of the school year to “set the tone.”

This became the Director’s Circle, a program for junior and senior students who applied or auditioned the prior spring to take on roles as designers, stage managers, or actors for the inaugural show of the year. The expectation was that these students would also act as leaders in the department and mentor the younger students.

The leadership structure that was created around this project injected a “healthy sense of competition” into the department, according to Kristy Leigh Hall (2003), a director’s circle alumna, Jeff Award-winning costume designer, Broadway and Hollywood costume tech, and head of Costume Design at the University of South Carolina. It paid exponential dividends, as incoming freshman would learn by example the high standards Ortmann aspired to and the intense work ethic he inculcated. The plays were rehearsed and built over summer break in the two weeks leading up to the start of the school year. Danny Adler (2005) told me that his Director’s Circle experiences rivaled the work he later did at NYU in conservatory. “Very adult, craft-focused, organic—he treated us like actors, not high school students.”

It’s worth noting that several people I spoke to about Niles North felt there were some downsides to the heavily structured program and to the creation of that elite group of Director’s Circle students. Kori Miner (2007), an alumna and teacher herself, said that while “she wouldn’t trade it for the world,” and that “so many of the good things about me are because of him,” for a lot of students who didn’t get more attention from Tim, “It was painful.” Miner added, “There was a lot of insecurity, a lot of fighting for his attention and praise.” Local parent and Jeff-winning actor Brian Parry echoed this, saying, “I agree that NN produced extremely high-quality work at a high school. Unfortunately a clear part of Tim’s operating procedure was to identify who were anointed and who were not.”

Still, this structure had an impact on Nathan Selinger (2014), currently a professional stagehand in New York. Selinger still remembers the influence the Director’s Circle production of Miss Julie had on him as a freshman with no theatre experience.

“I was absolutely blown away by the lighting and the set,” said Selinger. “There was an additional cyc they put in that showed all the changes and the time of day during the acts, and I just thought, this is the coolest shit I’ve ever seen!”

It’s no surprise that the student designers did such an incredible job. One ingredient in the Ortmann/Niles North special sauce was the professional artistic staff he recruited to work alongside and mentor the students. There was always a tech director/scenic designer, a costume designer (Teresa Ripley, who, Hall said, “could have won 10 Oscars in a parallel universe”) and a lighting designer (Jeff Award winner and DePaul professor Michael Rourke) on staff, as well as auxiliary specialists who would come in to work on choreography, hair design, or embroidery. Rourke said that Ortmann has “a grasp of the design process greater than some professional directors. He understands providing informative guidance without dictating the results.”

Students who worked with Ripley, Rourke, and his partner, professional lighting designer Barbara Reeder, weren’t just assisting adults; they were learning skills they would take with them for life. Kristy Hall stressed that everything she knows about costume construction she learned from Ripley.

“I am head of a graduate program that is an MFA of Costume Design and Technology—that is the design and the building of clothes,” Hall said. “I have absolutely no training at the collegiate level of the building of costume. I have what Mrs. Ripley taught me from the ages of 14-18 for 20 hours a week for four years.”

Former technical director-slash-scenic designer, “Captain” Eric Appleton, now a professor of theatre at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, said that the time he spent at Niles “changed his life.” Appleton was only at North for five seasons but was a beloved mentor and role model in that time. As Ortmann encouraged all students to work an allotted number of crew hours in addition to pursuing their onstage aspirations, many students found themselves in the scene shop with little knowledge but a willingness to work, and Appleton always found something for everyone to do, no matter their experience. This kind of inclusive mentality distinguished the program as elite rather than elitist.

As Appleton tells it, part of his own learning curve was finding ways to divide the labor of building ambitious scenery in a way that would also meet students at various skill levels and provide them with an education. Jeff Award winner Joey DeBettencourt (2005), who toured nationally with Peter and the Starcatcher before ultimately going to medical school, said that as a young actor in Chicago, he was able to support himself with the carpentry skills he learned from “Captain Eric” for years.

When asked for a representative experience of collaborating with Ortmann, Appleton recalls the production meetings for K2, which was done in the massive, multi-million-dollar, tension-grid-equipped black box second stage. Ortmann told Appleton, “Build me a mountain. Don’t take shortcuts. Don’t do symbolism. Build me a mountain.” That typified the ambition of the work.

Another show which typified the ambition of the work and also involved building a mountain occurred much earlier in Ortmann’s tenure, in Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun, an epic about the Spanish conquest of Peru. Indeed, multiple people cited this show as an early sign of the kind of ambitions Ortmann had for the department. Royal Hunt was staged in 1997, and alumni who were involved still spoke of it with awe. The set required a mountain with a working waterfall which poured into a grate on the stage.

Television actor Jonathan Kite (1998) recalled, “It was like, ‘What are we doing here? This is crazy.’ There were scenes where we would watch the rehearsal with that sun up there, and Franco (Atahualpa) in the chains, and I’m going, ‘This could be on Broadway.’”

Upright Citizens Brigade regular Marty Scanlon (2006) recalled seeing that show as a kid and having it change his life. “The moment he lifts up his dead son and the waterfall hits him and the lights turn red,” Scanlon said, “I was literally like, ‘That is a moment I will look back on for the rest of my life. I’m going to do theatre for the rest of my life.’”

More life-changing happened among students and faculty who were fortunate enough to work with Kabuki master Shozo Sato on Kabuki Medea (one of Sato’s legendary adaptations of a Western classic), The Monstrous Spider (a traditional Kabuki story), or Iago’s Plot (a Noh adaptation of Othello). Sato, a world-renowned Kabuki master, is well known in Chicago for a string of adaptations of Western classics he staged in the ’80s at Chicago’s famed Wisdom Bridge Theatre. Ortmann had studied with Sato at University of Illinois, and was thus able to invite Sato in as both guest artist and director to teach high schoolers the art of Japanese theatre.

Zachary Zirlin (2003), an in-demand graphic designer for film and television, said that working on Iago’s Plot was mind-opening for a young actor accustomed to thinking about acting in the Western tradition—i.e., from the inside out. Instead, for this Noh drama, Sato and Ortmann encouraged Zirlin to “memorize these body positions and movements, and it [the emotionality] will come from that.”

Wendy Schiller McGuigan (2001) said that the most jaw-dropping moment of her four years at North came during Kabuki Medea, while playing the princess whom Medea sets on fire. The illusion was achieved using a traditional Japanese costume called a hikinuki. McGuigan recalled, “It was painted with this incredible painting to look like fire, and it took two or three people to put it back together every time we rehearsed it. The level of delicacy with which we had to use these incredible costumes that we were lent—being allowed to do that was very cool.”

Kristy Hall, one of the costume technicians who helped achieve this hikinuki effect, said that Sato made clear that what they were learning was a trade secret, not to be shared. While Eric Appleton said he didn’t learn any trade secrets from Sato, he credits the Japanese American master’s example with driving him to be a better artist. Twenty years later, he still recalls a magical afternoon watching Sato add small drips of black paint to a huge drop that he and the students had painted, only to find that once he was done, the drop “came to life.”

It wasn’t only Ortmann’s ambitious theatricality and willingness to program culturally diverse work that pushed the program to radical heights; it was also his bold selection of plays that required uncommon maturity from the students. After Marvin’s Room in 1996, the big fish was A Chorus Line in 1999.

Brian Goldfarb (2001), who played Don, recalled, “I remember Josh Andrews joking during auditions, ‘They’re going to have to fly in people who can dance, sing, and act, because some of us can do some of those things but we can’t all do all of those things.’” But somehow the show came together well enough to merit a write-up in The Chicago Sun-Times. Columnist Neil Steinberg, who had a niece in the pit orchestra, was impressed with the quality of the work, but even more impressed with the maturity of the performers and the choice to omit nothing from the “raunchy” script (except for the word “fuck”). He made special mention of actor Ross Neihaus’s portrayal of troubled dancer Paul. “He not only delivered Paul’s searing monologue about the seedy New York transvestite dance scene convincingly, but did so in front of his entire high school, three nights in a row.”

An uncut A Chorus Line meant something in 1999, as did Marvin’s Room in 1996, and On Stars Not Falling in 2003. But Ortmann created an atmosphere where students felt safe to take huge personal and professional risks. Zachary Zirlin recalls the gay kiss at the end of On Stars. “I wasn’t scared to kiss one of my best friends onstage and then be bullied by anyone,” Zirlin said. “It felt like, yes, we’re telling this story, it needs to be told. He created an environment where that didn’t feel dangerous, it felt safe, and I think about that a lot.”

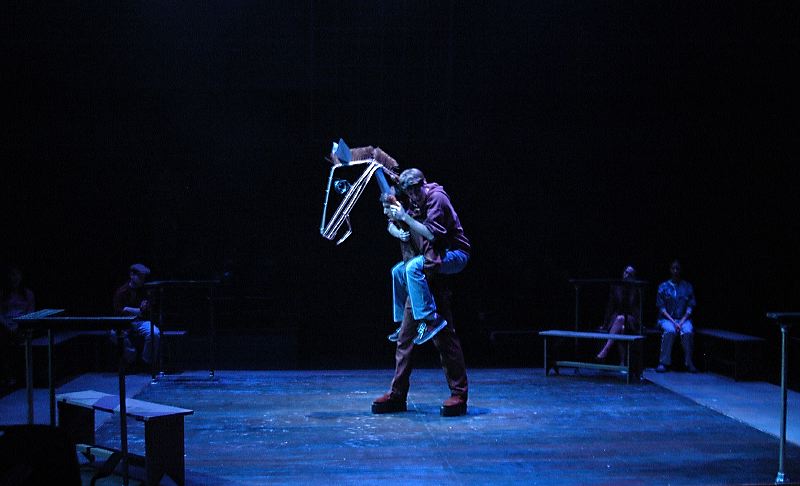

Marty Scanlon, who had his life changed by seeing Royal Hunt at age nine, would end up having his life changed again, this time as he acted in another Shaffer play, Equus, in 2005. He played the young lead, Alan Strang, and apart from excising the full nudity at the climax, the unsettling play was done in its entirety. It may have been the most adult undertaking Ortmann had ever attempted to date, and Scanlon says it was possible because the director had created an environment where it “was safe to fail. I went to school [later] to be a professional actor, and there weren’t many spaces where it was 100 percent safe to fail.”

Parents Lynn Floriano and Michael Boersma, who had two sons go through the program after Scanlon, echoed this, saying, “We felt the most valuable lessons learned were the vast scope of content and characters that our sons were able to explore in a safe space.”

Time and again, those who worked with Ortmann described his ability to create a safe space to fail as the thing that allowed them to transcend what some might believe to be the limitations of high school actors. That, and his high expectations. Scanlon said a lot of what was special about Ortmann’s approach was the way he treated his students like adult collaborators, expressing an unwavering confidence that told them, “I know that you have it in you and you will rise to it because you’re capable of doing it.”

Zirlin said the same ethos was true for the scenic design. When he sat down with Ortmann for their first production meeting for Laughing Wild, Zirlin remembers being blown away by the conversation. “I remember having those conversations about art and doing a conceptual show, and how to take Andy Warhol’s art and turn it into the concept for the show, and that was eye-opening. We were 16, being trusted to conceptualize with Tim, being equal parts of the conversation.”

Over his long tenure at Niles North, Ortmann demonstrated his various talents: as artistic director, producer, bureaucrat, and director. Nearly everyone I interviewed agreed that Ortmann could easily have been running a major regional theatre. Instead, through the rigorous pursuit of professional-grade work—and by the end of his tenure, Niles sometimes had eight-show seasons—some of the most important work he did was as an educator and as a human being.

Ortmann is gay. On the one hand, this was completely irrelevant to the work he was doing; on the other hand, it meant a great deal to the students he was mentoring. Said Jonathan Kite, “I remember thinking Tim might have been the first openly gay person I had ever met…there was such an awareness and openness that it was his identity, but it had nothing to do with his identity, and he was so strong of a human, he was strong enough for everyone. And all of these lost gay souls…I’m getting emotional talking about it. My brother was one of those people. And Tim was like, ‘I’m strong enough for everybody, you can come here and this is going to be a safe place for you.’ I don’t know where he’d be without Tim.”

Stephen Feder (1998), a successful Hollywood producer and Jeff-winning actor in his own right, recalls how Ortmann handled his teenage anger.

“What was interesting was that Ortmann knew how to take angsty kids, the heavy shit we were dealing with in our own lives, and rechannel those types of emotions into the stuff that we were doing,” said Feder. “I don’t want to say it saved my life, but it definitely taught me how to handle life.”

Feder’s contemporary Rom Bar-Nissim (1998), an entertainment lawyer in Los Angeles, thinks Tim really did save his life, because he entered high school in a bad place. He also was candid enough to tell Bar-Nissim he needed to “brush his teeth every day and wear deodorant.” At first, Bar-Nissim was “mortified” but later reflected that, “No one in my life, not even my parents, took the time to say, ‘Wash your ass, okay?’ And he took it upon himself because he knew it was not only going to affect the production but it was going to affect me in life. He had the courage to approach an awkward 16-year-old young man and say, ‘Look, you gotta do this, bro.’” Bar-Nissim also wanted to emphasize that Ortmann often cast him in roles he may not have been the obvious choice for, but which got at the heart of whatever struggle he may have been going through internally.

Emma Decker (2013) summarized the feelings many have about Ortmann’s emotional intelligence, and how it served the program:

He sees you for who you are. He sees through all the high school b.s. and sees who you are in your core, knows that potential, knows what you can live up to, what role you need to work through whatever trauma you were going through at that moment. Looking back, I’m like, Did he have magical powers? Could he see into my mind? The roles he gave me, that was my therapy. I didn’t have therapy in high school. He didn’t treat us like just kids; he was the director, he set the tone, but he allowed you to find yourself, he let you go on that journey yourself. I think that’s what made genuine raw theatre. After graduating, I find him as a friend. That’s so cool that transition can take place, and I think it’s a testament to how he treated us as students.

Everyone has an Ortmann story like that: something he said they needed to hear, or something he asked of them they’d never thought possible. Things both extraordinary and mundane. Ultimately, perhaps there isn’t much difference between a superlative director and educator, as they both require sensitivity and instinct, which Ortmann has in spades.

In my case, Ortmann saw a kid with huge walls up, hiding vulnerability behind the veneer of a class clown. He refused to accept any of my goofball antics and chose to treat me like a professional colleague from day one, with high expectations of what I could offer besides jokes and excuses. It was a hard-won battle, but he never gave up on me. I’m still trying to live up to the level of excellence he expected.

This approach to his students is what inspired his successor, Megan Baskin (2000), to take on the mammoth task of continuing his work. She told me that Ortmann is “the reason I’m a teacher. He knows how to ignite the best in people, and seeing him make people better at being artists and being human beings, being able to honor the best in someone—I don’t think I’ve ever seen adults be able to bring that out of adults as impressively as he does. That excited me.”

Jerry Proffit—who spent 25 years on the Jeff Award committee after retiring from North—told me that the very best work Tim directed equaled some of the professional shows he was seeing, and that Tim could direct professionally if that’s what he wants to do. Perhaps his next step will be more involvement with Chicago’s groundbreaking Definition Theatre Company, founded by alum Tyrone Phillips (2008), of which Ortmann served as founding board president. Said Phillips, “I am honored to push the needle of equity in the arts forward with him and am truly in awe of how many lives he has touched and changed for the better.”

One thing I can say with confidence: Wherever Tim Ortmann goes next, magic is sure to follow.

Clayton Fox (Niles North class of 2007) has written for Los Angeles Magazine, Tablet Magazine, Real Clear Investigations, and more. He is a long-time fan of American Theatre and is grateful to be able to write this feature in honor of the best storyteller he’s ever known.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Since this piece was published last week, AT has received several comments, both positive and negative, from former students and colleagues of Tim Ortmann. While we do not plan to do any further reporting or publish any more comments on this specific teacher and program at this time, we are considering more coverage of legitimate debates that have arisen in our field around best practices in teaching, particularly of young people.