An excerpt from Shy can be found here.

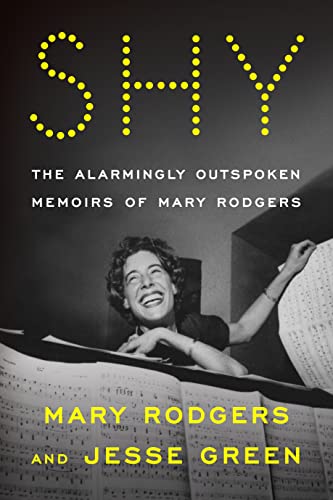

The new autobiography of composer Mary Rodgers is called Shy. But the ironic joke in that demure title is made blazingly clear by the book’s more accurate subtitle: “The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers.”

As told to, assembled, and well-annotated by New York Times theatre critic Jesse Green, Shy (the title actually refers to a song from Rodgers’s best-known work, the musical Once Upon a Mattress), is anything but. For musical theatre wonks, it’s a bonanza of upstage, backstage, and offstage showbiz gossip, advice, and reflections from a woman with a pedigreed vantage point, a sharpshooter wit, and a take-no-prisoners approach as a memoirist.

It’s an understatement to say that Rodgers, who died in 2014 at 83, led a colorful and extraordinary life. She was a gifted musical artist, a best-selling book author, a loving but often over-extended mother of a large brood (including Tony-winning Light in the Piazza composer Adam Guettel), and a dedicated arts patron. She was also the eldest daughter of Richard Rodgers, one of the most successful and influential composers in Broadway history—and for her, she makes clear, that was both a blessing and an agony. Her tell-all of family dysfunction, a chaotic love life, and a bumpy career read at times like a juicy cross between Moss Hart’s Act One and Christina Crawford’s Mommie Dearest.

In this case, it should be Mommy and Daddy, as she often refers to her parents, while exposing the child-rearing shortcomings that made them an aloof “god” and “ice queen” who swept a whole lot under the expensive Persian rugs. Or, as Mary puts it: “Pretense, lies, hypocrisy, and you’ve got a family crest.”

She also conveys warts-and-all portraits of her first husband (a closeted gay man who fathered three of her six children), various lovers (including legendary producer-director Hal Prince, an early squeeze), former pals she came to loathe (No. 1 on the hit list, a famously difficult writer she demolishes with the quip: “Talent excuses almost anything but Arthur Laurents”). There are also the collaborators who disappointed her (more than a few) and stars she was unimpressed by (including Judy Holliday, a “diva” whose final appearances were in a stage flop Rodgers composed). Not to mention an ultra-revealing chronicle of her nearly lifelong relationship (and infatuation) with Stephen Sondheim. (A central character in his musical Merrily We Roll Along was based on Rodgers.)

Since she refers to a slew of people who played roles in her life but are not household names now (if they ever were), Green’s many informative and clever notes at the bottom of the page are a bit distracting at first but quickly prove essential. As you read, it’s rather like working the room with the hostess of a fancy cocktail party as she tells tales about other guests she presumes you know—while someone else helpfully whispers in your ear to give you their thumbnail bios. (Like any good reporter, Green also researched her stories and found that most checked out, “no matter how outré.” Any factual errors, he assures, were corrected.)

Now and then, low blows and whiffs of bitterness bespoil the book’s generous spread of rich dish and hard-won wisdom. Her reaction to early drafts Green culled from their many hours of conversation: “Make it funnier. Make it meaner.”

But a saving grace of Shy is that Rodgers does not let herself off the hook either. She emerges here as a lusty, gutsy, complex woman who is admiring of those she loved and very candid about her own flaws—including extended addictions to prescription drugs and cigarettes, and a tendency to get involved with the wrong men and otherwise make bad, impulsive decisions. She acknowledges the privileges of her class (while underscoring she was “at the edge” of family wealth) and the influence and access she inherited. Most entertainingly, she’s a first-rate raconteur, and her hilariously barbed bon mots could give Dorothy Parker a run for the money.

Shy vividly, irreverently evokes the milieu Rodgers was born into, which for the most part no longer exists. Her childhood unfolded in a golden era of Broadway musicals, and within a family at the center of an inner circle of glittering opening nights, smash hits, soirees in swanky apartments on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and (briefly) poolside in Hollywood, amid snappy banter among geniuses. Her father was a Broadway titan who, with lyricist partners Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein II, created such theatrical classics as The Boys from Syracuse and Babes in Arms (Hart) and Oklahoma!, Carousel, and The King and I (Hammerstein), as well as a large chunk of what is now known as the Great American Songbook.

But like many children of immense privilege, her youth was unenviably fraught. She declares, “I doubt my parents even really wanted to have children, not the way children want to be had.”

With self-deprecating but rueful humor Rodgers portrays herself as a scrappy misfit growing up in a ritzy but chilly, furtive household. At home Daddy was often taciturn and laser-focused on his work. (“When he was writing, it was sacrilege to interrupt or disturb him in any way.”) He was also an alcoholic (a bottle of vodka a day at times, with some bottles hid in the toilet tank), and a serial philanderer with what Mary calls a major “case of Great Man-itis.”

His snobbish socialite wife, Dorothy, was occupied with charity work, interior decorating, and writing books about their graciously appointed home life—“basically fantasies,” in Mary’s view. Neither parent had much time, nor inclination, to nurture their two daughters emotionally. And though he did support her musical endeavors (financially and otherwise), Daddy Rodgers once bluntly informed the young Mary, “We love you but we don’t like you.” (She mostly felt the same way about them.)

Still, while often expressing ambivalence about his character, Mary leaned on her father (mostly great about the big things, like rescuing her from financial ruin a few times) and deeply admired his artistic achievements—with exceptions like “the goddamn praying larks and uplifting hymns for contralto ladies” in The Sound of Music,” and “the lovers’ songs in The King and I—ugh”). Moreover, she was grateful to him for giving her an early musical education, including taking her along to technical orchestra rehearsals for his musicals with Hart.

It was her mother she found difficult to forgive. Dorothy Rodgers is described as “hard, cold, stuck within herself,” a haughty Jewish antisemite who was also “two-faced about race” (pro-Civil Rights but wouldn’t hire a Black maid), and constantly disapproving of her problem child, the mischievous, unglamorous Mary—who at one point was packed off, like “an orphan of privilege,” to a rigid boarding school. “Is it a surprise that I became, as the nursery rhyme says of me, quite contrary?” Mary writes.

Later as, a fish out of water at Wellesley College (“the place was filled with Amazonian jocks”), Rodgers began to write music of her own. But her ambitions were mired in insecurity: “I had low expectations of myself, that way I could fulfill them. I was so conscious of working in my father’s field that I would choose to cultivate corners of it where no one was looking or would notice if I flopped. Children’s songs. Christmas songs.”

Apprenticing at a summer theatre, the Westport Country Playhouse, she found her tribe: “I thought…These are the people I want to spend my life with. They were theatre people, you could smell it, the way dogs smell certain things, only instead of meat it was imagination, iconoclasm, fearlessness, a gift for fun.”

By her mid-20s, Rodgers had a batch of published songs—plus three small children and a highly problematic marriage with a prominent lawyer. She praises him in Shy as essentially “an extremely good guy” and devoted father. But he was so frustrated at having to mask his sexuality in the rabidly homophobic 1950s that he took it out on Mary (at times violently). In retrospect, she empathized, saying: “What a wretched time to be a gay man! And what a wretched time to be a naïve, overly protected, headstrong young woman.”

Juggling the challenges of music, marriage, and motherhood, Rodgers launched her professional career writing “ditties, jingles and kiddie numbers” for television, gems like “Lassie, My Four-Footed Friend,” and material for kids’ show host Captain Kangaroo—whom she uncharitably describes as “a fat guy in a bowl haircut who named himself for a marsupial and looked like a little child molester.” (For what it’s worth, the latter phrase, Jesse points out, is an arcane reference to a key clue in the film The Last of Sheila, which Sondheim wrote with Anthony Perkins.)

Alongside a young Woody Allen, she wrote for adult TV as a composer for The United States Steel Hour anthology series. More congenial and meaningful was a long stint working with an admired friend, composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein. She helped produce his New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concerts series, landmark TV broadcasts that gracefully educated a generation of kids about classical music. She also found a simpatico lyricist (and fellow amphetamine addict) in Marshall Barer, with whom she shared the “exhausting, thrilling, euphoric” creation of Once Upon a Mattress, the charmingly goofy Broadway musical comedy based on “The Princess and the Pea.” Her nuts-and-bolts accounts of the evolution of that 1959 hit show (which starred a young, marvelous Carol Barnett and has been revived often) would be instructive for any aspiring theatre composer.

Likely to generate the most buzz out of Shy is its frank account of her complicated connection with Sondheim—or, as she calls him, at one point, “the love of my life.” She was in awe of his brilliance, and they virtually grew up together (his mentor was Oscar Hammerstein II) and traveled in the same lofty circles, bonding over music, parlor games, and a similarly edgy sense of humor. Though she knew full well he was gay, Rodgers was so needy after her first marriage ended, and so enamored with “Steve,” that she agreed to his attempt (under a misguided therapist’s instruction) to move toward sex and marriage with her. But when they slept together, she notes they would “get into the same bed, side by side, frozen with fear,” barely touching. It was clearly a failed experiment that went on too long, and was “wildly uncomfortable” for both of them. It isn’t a comfortable read either.

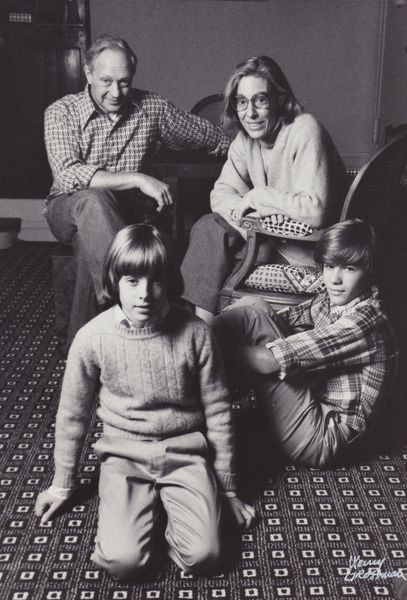

But their close friendship survived, and Sondheim pops up throughout the book. She later found the right marital partner in kind-hearted, supportive Henry “Hank” Guettel, a sometime film executive and theatrical producer, and for over a decade the beloved executive director of the nonprofit Theatre Development Fund (the organization that runs New York’s TKTS ticket booths, among other programs). He was presumably quick with a quip too: According to Green, playwright Paul Rudnick dubbed them “the Nick and Nora Charles of Central Park West,” a reference to the sophisticated upper-crust detective couple in The Thin Man movies.

With Guettel, Rodgers delivered three more offspring (one of whom died suddenly as a young child, a wrenching tragedy Rodgers movingly describes). And she fitfully continued to compose, though many theatre projects (including a musical based on the Carson McCullers novel and play The Member of the Wedding) “went nowhere” for various reasons often beyond her control (bad timing, bad backers, bad idea, or plain old bad luck).

After years of “wasted work,” she stopped trying to work in theatre altogether, because she “didn’t have the stamina to tilt at windmills…or the financial wherewithal to support my family.” Appreciation for her craft came later, in the 1997 cabaret show Hey, Love: The Songs of Mary Rodgers, for which Richard Maltby Jr. assembled 18 of her songs and wove them into a revue, which was praised by New York Times critic Stephen Holden as “a tautly witty psychological and musical patchwork about love and its discontents.” (There’s also an original cast album.)

One wonders if Rodgers would have fared better, career-wise, in a more feminist and post-feminist theatre, as opposed to the hyper-commercial, male-dominated theatrical era of the 1950s and ‘60s. In any case, she turned to other pursuits, penning 1972’s Freaky Friday, a novel for young people about a mother and 13-year-old daughter who swap identities. It became a best-seller, ushered in a new writing career, and spawned movies and a stage musical.

At a certain point, considering herself a failure as a composer (especially compared to her father and Sondheim), Rodgers turned to patronage. She was a stellar board member of the Juilliard School, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and other important arts organizations; she helped to manage the rights to the still in-demand works by her late father and Hammerstein (Shy includes her candid opinions about major revivals and adaptations of their shows); and she offered quietly generous support for the careers of talented young artists and other causes she believed in. She even came to understand and achieve peace with her difficult mother.

She short-changes those later years a bit in Shy, but we learn something about them from Green’s affectionate afterword, which also outlines their collaboration on the book over several years and the pleasure of her company and Guettel’s. “There was no social snobbery, their parties were an aristocracy of talent,” writes Green. “They flipped the template of the richest people I knew, who were generous within the narrow orbit of family or in the far heavens of philanthropy but nowhere in between.”

Though Mary Rodgers worried that the memoir of a “second-drawer composer and children’s book author” would generate little interest, Green writes that she “wanted readers to have a good time, even when learning about the times she did not.”

Mission accomplished, and then some.

Seattle-based critic Misha Berson (she/her) is a frequent contributor to this magazine.