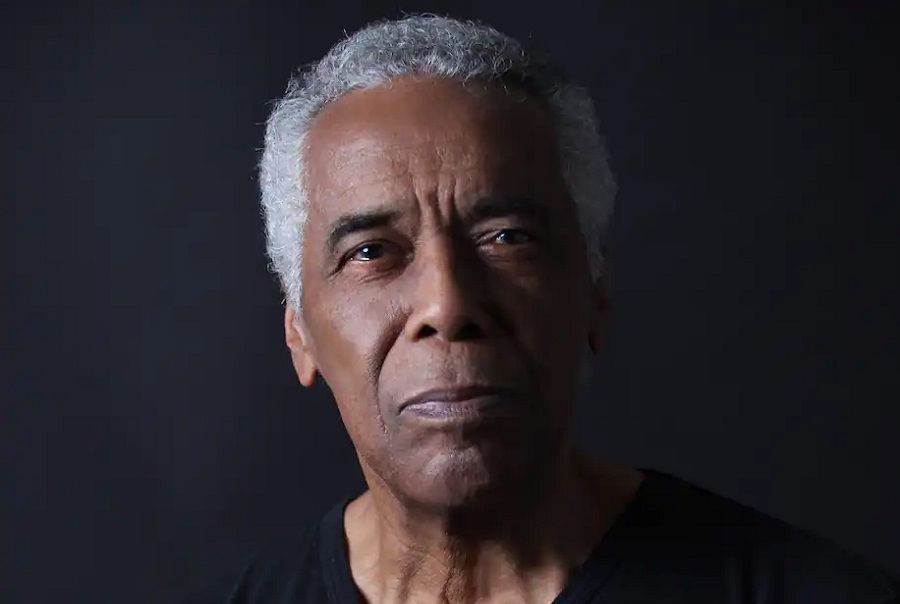

Actor, producer, and cultural activist Robert Hooks is now best known as one of the founders of the historic Negro Ensemble Company (NEC), where he served as executive director and producer. But his career stretches beyond that milestone; he also created two other major Black theatre companies during the 1960s, and worked as an actor on Broadway, on TV, and in film for decades. Among his numerous awards and accolades are an NAACP Image Award for Lifetime Achievement, an induction into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, a producing Emmy for his PBS special Voices of Our People, and a Tony nomination for his lead role in Hallelujah, Baby! At NEC, he helped guide the company’s productions to 11 Obie Awards, 2 Tony Awards, 4 Vernon Rice Drama Desk Awards, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, one Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and other distinguished theatre awards.

I spoke to Hooks, now 85, earlier this year about his extraordinary career.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: Mr. Hooks, you were born and grew up in Washington, D.C., the youngest of five children. How would you describe your childhood there, and how did it lead you to the theatre?

ROBERT HOOKS: We grew up in what’s called the Foggy Bottom in segregated Washington, maybe 10 blocks from the White House, but still segregated Washington. My street, Newport Place, was one single street wedged between 21st and 22nd, and N and O Streets, in Northwest Washington. I was nine years old when I started acting. My oldest sister, Bernice, was a recreational counselor in the summer; she would do things and events for the community. This particular summer she was putting on a play called Pirates of Penzance. She didn’t ask me, she told me I was going to be in the play. I said, “You got to be kidding me. I’m not going to be in some play. My buddies will all run me off the block.” I just said, “I won’t do it,” and she said, “You will do the play.”

We all lived in a railroad flat. There was one bed for all five of us. We all slept in that one bed; the girls up top, boys at the bottom, and being the smallest, I was kind of stuck in the middle. I continued to refuse to do this play, but my sister—well, all the Hooks have very big toes, but my sister Bernice’s big toes were bigger; she could lift things with them. So I’m still denying, “I’m not going to be in your play,” and one night, I’m lying in the bed, and I feel Bernice’s big toe in my thigh. She gave me this vise-like grip. I didn’t want to yell—I’m nine years old, and there was no noise in bed—so I tearfully relented and agreed to do the play.

The auditorium was packed. It was at Francis Junior High School. I was in elementary school at the time, but the plays were done at Francis, which was in the Georgetown neighborhood, a couple of blocks from my house. I had never been on the stage, but we had rehearsed, and thanks to Bernice, I knew what I was doing. The play ran for two weeks and sold out every show. All my buddies said how much they liked what I did in the play. That was the start of being on a stage and loving what I was doing up there.

When summer was over, I went back to school. One of my teachers had seen Penzance and decided she wanted to start a drama club at Stevens Elementary School, and she wanted me to be a part of it, which I was happy to say yes to. When I graduated and went to Francis Junior High, I joined the drama club, and continued drama at Armstrong Senior High School. The school drama groups taught me discipline and even made me a better student in my regular school classes too.

Then my mother married Joe Dickerson and moved to Philadelphia to live with him and his five young children. It was certainly a new life of adjusting for me. I was in my first year of high school at West Philadelphia High. For the first time in my life I was attending an integrated school, and that reality blew my mind. West Philadelphia High had a wonderful drama club. I graduated in June 1956 and got a job, though my mother and everyone else wanted me to go to college. In fact, I did apply to Temple University and was accepted. But as it turned out, I never attended Temple; I was too busy studying drama at the Bessie V. Hicks School of Drama.

I came across material that stated you actually met Malcolm X. Can you say more about that?

I had moved to New York, and I was working as an IBM machine operator at a sweater factory, Greyson-Robinson and Company. And there was this small, very energetic Asian woman who was an employee in the sweatshop, Yuri Kochiyama, who also worked to protect the sweatshop employees against management and the owners. It turns out she was a popular New York Civil Rights activist and union organizer. She would have Friday meetings at her Harlem apartment with Greyson and other garment district workers. I always wanted to know what moved her to do that, and I asked her to talk to me about what she was doing with and for the workers. She invited me to a meeting at her apartment up in Harlem. She and her husband Bill had a big family; they were a Japanese family that had become American citizens. But Yuri was always into Civil Rights, and she also knew, and worked with, Malcolm X.

One Friday evening I’m sitting there at a Kochiyama apartment meeting, and Malcolm walks into the living room. I almost fell to the floor in shock. You could see him orating on the street corners in Harlem, which I did on occasion because I lived there, but I never thought I would be face to face with him. Except now I was in Yuri Kochiyama’s apartment, where this was obviously possible. So Malcolm came in to talk, and I just happened to be there that Friday. I stood in the middle of the floor with Malcolm. I shook his hand, we chatted, and I was shaking in my knees.

You also met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. What was your experience like with Dr. King? YOu mentioned that he helped you to realize how you could fulfill your political responsibility to society.

It was a very interesting experience, and I will remember it for the rest of my life. I was doing a play called The Blacks, a Jean Genet play, which had taken New York theatre audiences by storm and astonished them with its artistic and political power. All the top-flight Black theatre actors working at the time did The Blacks at one point or another in its historic Off-Broadway run. The show opened during the height of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement at the turn of the 1960s. Leaders of organizations like NAACP, Martin’s organization SCLC, SNCC, and CORE would raise needed operational funds in New York City. I was doing The Blacks and producer Sidney Bernstein came back to the dressing rooms and said we were going to have a surprise that night—that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta, were coming to see the play.

Now, I’m doing one of the play’s leads, Deodatus Village, which is just a great role. I came in to replace the brilliant James Earl Jones in that role and had worked my ass off onstage to make the role my own. The night when Dr. and Mrs. King are in the audience and enjoying the show, I’m centerstage as Village delivering a commanding monologue. At one point in my speech, I choose a member of the audience; I always chose to address a woman in the audience. In this case, Martin and Coretta were sitting right on the aisle in the St. Mark’s Playhouse. I zeroed in on Coretta, thinking she would be a little nervous, but that’s okay—I would have fun with that. But she wasn’t. It was like she was a part of the cast, she was so good. She was responding to me and I’m looking at Martin, and Martin is looking at her as if to say, “What the heck’s going on here?” I did the whole monologue with her—to her. They came backstage afterwards. We took pictures, and then we went and had food and drinks at our favorite after-show hangout spot, the Orchidia, all on the tab of our producer, Sidney Bernstein.

Now here I am sitting across the table from our righteous hero Martin Luther King, apologizing to him for not being with him and the others on the frontlines in the South—I mean, I’m up on the stage acting and having fun in New York. He said, “No, no, no, hold on. Just stop right there, young man.” And that’s when he explained to me, “What you all are doing on the stage, what these writers, the Black writers, are writing about, what you’re doing up on that stage for the Black community and everyone else is just as important as what we’re doing on the front lines in the South. So keep doing what you’re doing, representing Black folks.”

That encouragement from Martin really meant a lot to me. Malcolm was doing his thing his way, and Martin was doing his thing his way. And I admired them both. I befriended them, and we were friends over the years.

In 1960, you made your Broadway debut replacing Louis Gossett Jr. in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, and then you went on the national tour with the play. You mentioned that you’d seen the original production of Raisin in the Philadelphia tryout before it arrived in New York City. Let me ask you three questions together on this one: How did you make this happen? What was it like working with that cast? And what was the experience like working with the director, Lloyd Richards?

It was a great and life-changing experience for me. I saw the play in previews in Philadelphia, the first Black play I had ever seen in my life, the experience prompted me, a few months later, to just pack up and move to New York, because I knew I wanted it. When that curtain went up on A Raisin in the Sun and the lights went up, I thought I was in my own living room on Horton Street. That’s what it looked like, and that kind of got to me. I’m sitting there at the end of the play crying like a baby because of what I felt watching people who looked like me on that stage telling their own story; it just took me aback emotionally. The applause was so exciting and amazing; I was the first one on my feet, yelling “Bravo” and clapping—so much so, I broke the band on my wristwatch and the whole thing fell on the floor and I couldn’t find it, I was too busy clapping and yelling. That defined it for me.

After I saw Raisin in Philadelphia at the Walnut Street Theatre, I just had to go backstage to meet this amazing cast. I couldn’t get into Sidney Poitier’s dressing room because it was too crowded; I couldn’t get into Claudia McNeil’s dressing room because it was also too crowded. And then I looked down at the end of the hall to the men’s dressing room, so I go down there to meet some of the guys. I walk in, there’s Ivan Dixon, Lou Gossett, Douglas Turner Ward, Ed Hall there’s Lonne Elder III. And there’s young Glynn Turman—at the time he was just a youngster playing Travis in the play. Now he’s doing grandfather roles, for crying out loud! That’s how long ago it was. Anyway, I start talking to these guys, and I tell them I’m a local actor, and ask them what they thought I should do. I said, “There are no roles for me here in Philly.” Lonne Elder chimes in, “Well, come on up to New York and join the unemployment line like everybody else.” We all got a big laugh! They were so nice to me; I couldn’t believe the warm welcome they gave me.

A few months later I had moved up to New York to pursue an acting career. By then, Raisin was a big smash hit on Broadway. I go backstage, and I started hanging out with these great guys I’d already met in Philadelphia. One day I’m walking down 47th Street and I run into Ed Hall—actually, he was an understudy for Lou Gossett and Ivan Dixon. And he says, surprisingly, “Bobby, you should get over to Phil Rose’s office now, because Lou Gossett is leaving for Hollywood and they’re going to replace him.” I thought wow, this is my opportunity, right? But I’m also thinking, Ed Hall was the understudy for Louis and Ivan—why isn’t he replacing Louis in the role? I never learned the answer to that. But I ran up Broadway to 57th Street, 10 blocks up Broadway to get to Phil Rose’s office to audition, to be Lou Gossett’s replacement in the biggest Black play on Broadway. I run into the building. I go up to the seventh floor, and I don’t know which room it is, but the elevator door opens, and this little guy appears; I almost ran over him. I asked, “Could you tell me where Phil Rose’s office is?” He says, “It is right over there.” I rush in and the little man comes in right behind me. Yes, it was Phil Rose that I almost took out coming out of the elevator.

Phil Rose asked his assistant to bring a script in so he could audition me. He asked me how I knew about the role, since they hadn’t even officially announced it. I said, “Ed Hall told me about it. And Mr. Rose, I really don’t need a script. I know the role; I know all the lines; I know all the lines of everybody in the show.” He said, “Well, do you mind if I have a script? I don’t know the lines.” I read with him, he liked my reading, and he called the theatre immediately. He told me to go to the theatre because director Lloyd Richards was there. I’m blown away. I’m going to go read for Lloyd Richards, to replace Lou Gossett! I get to the theatre. I walk out on the stage. I’m standing there in the street just outside the stage door and Lloyd Richards walks out, and then from the wings walks the actress Billie Allen, who was Diana Sands’s understudy in the play. She and I get set to read the two scenes. After the first scene, Richards liked what I did and gave me a couple of notes for the second scene. I read the second scene as well. I’m feeling great, I’m feeling fantastic. And he dismissed Billie and he says, “We’re not going to audition any other actor for this role. It’s yours. Have your agent call Phil Rose’s office.” Well, guess what! I didn’t have an agent. I didn’t tell him that, but long story short, Diana Sands was so happy for me, that Diana called her agent and he represented me and made my deal for A Raisin in the Sun.

In 1961, you replaced Billy Dee Williams in the Broadway production of A Taste of Honey and went on the national tour with that show. A Taste of Honey was being produced by David Merrick, and at the same time you were in his show, you were picketing Merrick’s Subways Are for Sleeping, which was on Broadway and did not have any Black dancers or singers. I also read that at that same time, Merrick was mentoring you to become a producer. What is the story behind this?

David knew that I was picketing Subways Are for Sleeping while I was doing A Taste of Honey. I did three Broadway plays for David Merrick. He liked me, even though I was picketing another one of his shows. He understood my commitment as a Black artist. One day while I was on the picket line, his right-hand man, Jack Schlissel, walked over to me and said, “You know David Merrick likes you. He has to like you because you would have been fired in a hot minute for picketing his show.” I learned a lot from David Merrick, who was one of the top producers on Broadway at the time, though not the nicest man to other actors.

You replaced actors in many of your Broadway roles, but in Tiger Tiger Burning Bright in 1962, you finally created your own role with the character Dewey Chipley. I notice that your name was listed as Bobby Dean Hooks at that time.

That was my real name before I changed it. I changed it when I did Dutchman, because my dear friend Roscoe Lee Browne came on opening night to see me in that, and we went out for drinks afterwards and he says, “You’ve got to get rid of that Bobby Dean. What you did on that stage tonight, you were Robert Hooks.” I changed it while I was still doing Dutchman. From that point on, my professional name was Robert Hooks, but everybody that knew me from back in the day still calls me Bobby, and that’s okay.

You mentioned that in 1962, you replaced James Earl Jones in Jean Genet’s The Blacks. Every major Black actor of the time was in that legendary production. What else could you share about that production that most people do not know?

First of all, it was a legendary play, and the original cast was just phenomenal. A lot of people who were in it—Roscoe, Cicely, Maya Angelou—would go off and do other shows, TV shows or whatever, and the producer would let them go. Then they could always come back to the show when that gig was over. I did it three times, because I was in the play for quite a bit, but I would be called off to do a movie or TV show or another play, and I could always come back. A lot of people didn’t understand how the understudies took that. Well, the producer let everybody know he was going to do this. We all wanted to go back to The Blacks because it was so incredible, and the producer always let us come back.

In 1964, you were in Tennessee Williams’s The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore. You played the role of the stage assistant and Tallulah Bankhead was the star. What can you tell me about that experience?

I had a wonderful relationship with Tennessee, and with several of the other people in the play, including Tab Hunter, who was doing his first Broadway play at the time. Tennessee and I drank after the show; he drank like crazy, but what a brilliant man. And I had a great time being his friend.

The role that I played in The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore was not written in the original play. They had done the play the year before, and Tallulah Bankhead wasn’t in it then either. The two new characters Tennessee wrote for this production were called Stage Assistants. They were kind of like Kabuki characters, played by me and the fine actor Conrad Mathieu. We were the two characters that were added to the new production of the play that was done the following year; the play had opened in 1963 with a different cast. It didn’t work, it got terrible reviews, but Tennessee Williams said, “Look, let’s get Tallulah Bankhead to do it.” They did it the very next season, which is really rare.

Tallulah Bankhead, this wonderfully talented woman, drank a lot, but when she was in action onstage you’d never know she was soused! Also, Tallulah possessed a mane of thick, gorgeous hair, and she liked me to come in and brush it for her. It was fun. She called me in every night; I would brush her hair and we’d talk politics and Civil Rights. She reminded me she was a friend of the Kennedys. We would talk presidential politics. Then one afternoon, while in rehearsal, came the moment that stopped time for us on Broadway, and for many around the world. Conrad and I were taking a break; we’re standing there, and cars started screeching and pulling over, people were yelling, “They shot John F. Kennedy in Dallas!” I knew John F. Kennedy was a friend of Tallulah’s.

I had to go in and tell Tallulah what had just happened, but she was onstage working with the director, Tony Richardson. She’s sitting on the stage in a chair. Tony’s on the apron of the stage and they’re talking, and I walk in, and Tony looks at me as if to say, “Come on, Bobby, I’m rehearsing here.” I walked over to Tallulah and I whispered in her ear that John F. Kennedy had just been shot and he’s dead in Dallas. She has this great voice, a very heavy voice. She let out this sound; it was almost scary. It was like out of one of the horror movies, and she raised herself out of the chair and fell backwards and fainted on the stage. Tony, of course, was going out of his mind. “What the hell is going on?” I told him. So when people ask, “Where were you when John F. Kennedy was shot?” It’s easy for me. I was doing a play with Tallulah Bankhead, and we were in rehearsals, and it was an amazing, scary scene, because I thought maybe she was dead.

You actually played Clay in the original stage version of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman in 1964. Most people know the movie version with Al Freeman Jr. as Clay. What was it like creating Clay for the stage?

I saw a reading of that play when they were trying to get the producer for it. Al Freeman Jr. was reading the role of Clay. They finally ended up taking the play to Edward Albee and his company, Theatre 1964. Then I get a call from my agent, saying that they want me to come in and talk about doing Dutchman. I say, “But I thought Al Freeman Jr. was doing it?” For some reason, they still offered me the role. Al never did the play at all onstage. The play was a big success and they bought it for the movies. Then Al did the role in the movie, but a lot of people get confused and think that Al Freeman Jr. originally did Dutchman and I took over the role from him. Al did the movie version; he was wonderful in the movie, as was Shirley Knight—but Shirley was no Jennifer West. I did the play with Jennifer West. Man, she was so brilliant every night. The play Dutchman hit the live audiences harder than the movie version.

In 1965, you played the lead in the New York Shakespeare Theatre Festival’s production of Henry V. It was called a “triumph” by a critic, who said, “Robert Hooks’s King Henry was especially good, combining fiery grace with an almost tragic sensitivity.” You were 28 and you were the talk of the town. What did all of this mean to you at that time?

At that point, of course, Joseph Papp, the producer of New York Shakespeare Theatre Festival, had seen me do Dutchman and The Blacks. He had also seen me do Tiger Tiger Burning Bright. He said, “I’ve been following you. I’d like you to consider doing Henry V in the park.” And I thought, ”Am I ready to do Henry V?” I asked Papp that same question. He said, “No problem, no problem, I’ll work with you, and you’ll be fine as Henry.” Usually, they’d go after James Earl Jones or somebody, but Papp wanted me. We labored hard on my approach to the role, and it turned out beautifully in the end.

By this time, I had already started my first theatre company, the Group Theatre Workshop, with a group of youngsters from the mean streets of New York who wanted to be in the theatre. I was working out of my living room. I even reconstructed it, and together with the students built a stage right there in my rented apartment. I had these great kids off the streets of New York, from all five boroughs, maybe 60 or 70 students, coming into my apartment every day, studying acting, voice, movement, and reading and performing poetry. There were some incredibly talented young actors: Hattie Winston was one of them, Antonio Fargas was another. Just a lot of excited young theatre wannabees, 18- and 19-year-olds.

Because these were youngsters, and I wanted to experiment and do a real adult stage piece, the young performers would have to play grown-up roles. Douglas Turner Ward, who had written two hilarious new comedies, Happy Ending and Day of Absence, had gotten a producer friend to option his plays and was trying to get financing to produce them. I had personally helped him in doing it. We would constantly do backers’ auditions. But his friend couldn’t raise a dime or get any interest from backers at all. I asked Douglas to let me do the smaller play, Happy Ending—it’s a four-character play, and I had some good young actors who could play the grown-up roles.

While producing, you continued your acting career. In 1967 came Hallelujah, Baby!, which won the Tony Award for Best Musical, and got a young Leslie Uggams the Tony Award for Best Leading Actress. Arthur Laurents was the book writer for the show. Did you have any dealings with him?

He and I had a few little problems with how I was interpreting my character, who starts off as a Pullman porter, then goes into the military, after which he becomes a Civil Rights advocate. I didn’t have any serious problems with Arthur’s take on my character portrayal, because it was understood from the very beginning that it was up to me to do the role as I saw and felt it, and if some dialogue wasn’t right, I just said, “I can’t say that.” Burt Shevelove, who directed it, and Betty Comden and Adolph Green and Jule Styne, four of the most heavyweight Broadway musical people ever, were with me all the way. They wanted me to be happy with my character. Arthur and I had our little story thing, but everybody else was happy with what I was doing. I was acting, singing, dancing, and creating a dynamic character. I didn’t win the Tony Award, but I was nominated for it, which for me was just as important career-wise.

What happened the night of the actual televised Tony Awards to the world was a weird and mind-blowing experience for me. I was up for the award with three other actors: Robert Goulet, Tony Roberts, and David Wayne. Diahann Carroll had been asked to give the award for the Best Actor in a Musical. She came backstage, glided into my dressing room and we hugged, and she said, “Oh, I hope you win.” Mind you, she was presenting the award. I had written a little acceptance speech, just in case. I’m sitting out in the house after we did our performance. Finally it comes down to the Best Actor in a Musical. Diahann is up there looking gorgeous, and she’s got her envelope. She opens the envelope, and she looks over my way and she said, “The winner is Robert.” I actually had gotten up and I am out of my seat, I was on my way out to the aisle…and she finished, “Goulet.” And there I stood in the aisle, looking like a fool. I’ll never forget that. I went backstage afterwards, and I said, “Diahann, how could you do that?” She said, “Well, you know, Robert Goulet is a friend of mine too.”

You were one of the founders, along with Douglas Turner Ward and Gerald Krone, of the Negro Ensemble Company. There has been so much shared about how the Negro Ensemble Company came into existence. What do you think has not been told about the creation of that company?

Because I had produced Doug’s two one-acts to great success, the attention and acclaim led the Ford Foundation to ask us to propose what our ideal Black theatre company would look like. The three of us knew exactly what we wanted to do. We wanted to create a continuum; we wanted to do more than just a play here, a play there. We wanted to do a series of plays every season. We had a training program; incidentally, the Group Theatre Workshop, my early company, became the training program for the NEC. Nobody had ever done it before. Nobody’s ever done it since; we’ve created opportunities. We’ve done over 450 plays. Actors, you name them, they came through the Negro Ensemble Company, including Denzel Washington and all the rest of them. I am proud of our accomplishments. We decided we wanted to create something different. We wanted to create something that would leave a legacy, which we’ve done. Not too many other theatre companies can say that.

In 1980, you, Sidney Poitier, Maya Angelou, Brock Peters, and Cicely Tyson went to Washington to testify before Congress on the state of Black artists in the entertainment industry. What would you like to share about that experience?

We were trying to get the industry to open its doors and level the playing field for Blacks to come into the industry as producers, directors, writers, whatever. There were all kinds of problems with white producers doing Black material; they just wouldn’t do it. So there was a dire need. Washington had to hear it. We were friends with congressmen and congresswomen. I think it was Mickey Leland from Texas who was with us when we went to Washington. We also did one out here with one of the Congress people out here, but we got them to open up. It’s in the Congressional Record. We did it twice in Washington with the people you just named—we all sat in front of Congress and let them know what the problems were in the entertainment industry. And it worked. After we did those Congressional hearings, the industry opened its doors to Black producers. One of our dear friends, Charles Johnson, became one of the top Black producers in the industry. We wanted to level the playing field for Black talent on all levels, not just actors or dancers and singers but in administration, producing, designing.

How would you like to be remembered?

The main thing I want people to remember about me is that my career and my success are more than myself, which is really the title of my upcoming book. What I’ve done, the legacy that I leave, is what I’ve done for others, what I’ve been able to do for other artists in this industry, Black artists in this industry. Acting is fine, and the credits are nice and all that, but that’s not why I’m in this industry. That’s not why I have been successful in this industry. It’s because I’ve done things for other people. And I’ve enjoyed doing things for other people, starting all the way back to the Group Theatre Workshop with those kids I got off the streets of New York when they didn’t have any place to go. And now their careers are blooming. That’s what I want to be remembered by.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.