The Avignon Theatre Festival in France is one of the largest in Europe. For three weeks, the ancient walled city of Avignon hosts thousands—yes, thousands—of productions, most of them in the fringe or OFF Avignon program, which this year comprised 1,580 productions, including circus, mime, dance theatre, multimedia, and solo shows, in addition to comedies and dramas. Besides performances, the festival offers exhibits, film series, round tables, documentary series, “thought workshops,” and numerous professional development opportunities.

How does a town of roughly 90,000 souls accommodate so much theatre? For the duration of the festival, every corner of this 14th-century city is transformed into a space for performance or special events, including museums, churches, castles, courtyards, schools, gymnasiums, the city university, restaurants, and actual theatre spaces that operate year-round. Performance spaces in Avignon may only be outnumbered by cafés and eateries, which line every street and square and nestle in the courtyards and gardens of various monuments and complexes. During my recent 10-day visit, I was struck by the all-encompassing celebration of the arts reflected in creative street decorations, murals, and the joy expressed by everyone about theatre. On my first day, I found the streets bustling with performers promoting their shows in costume, singing and dancing or just walking up to people with a flyer to talk up their show. Every wall was covered with show posters and everyone was talking about theatre. I felt like I was in theatre heaven!

This year’s festival, which ran July 7-26, marked its 76th edition, and the last year of programming by longtime artistic director Olivier Py, who has had the post since 2007. Some in the French media were surprised when Portuguese theatre artist Tiago Rodrigues was selected to replace Py, as this will be the first time a non-French national leads the festival. But if I learned one thing during my visit, it is that Festival d’Avignon is a truly international endeavor, with artists from nearly every continent participating, and performances in French predominantly but also in Arabic, Persian, Greek, Chinese, Zulu, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, English, Russian, German, etc. I was particularly impressed by the remarkable lineup of artists of Middle Eastern and North African heritage, whose work made up nearly a quarter of the shows in the official main program.

The first show I saw at the Festival was presented at the Opera Grand Avignon. Tiago Rodrigues’ adaptation of Racine’s Iphigénie, directed by Anne Théron, one of the few women directors in the festival, had the narrators and characters describe the play’s events as memories. Many lines were preceded by “I remember,” which made us question the accuracy of what we were being told, especially when the characters disagreed on their versions of the facts or refused to speak their line as the narrator decreed it. According to the program, with this adaptation Rodrigues means to imagine what would happen if men were not compelled to follow the gods’ commands—a question which inspired Theron to examine the narrative from a woman’s perspective. An impressive Mireille Herbstmeyer as Clytemnestra propelled the core of this examination, questioning the inevitability of the sacrifice and encouraging Agamemnon to “remember” an alternative ending. Ultimately Agamemnon could not, despite his deep anguish, and Iphigenia accepted the gods’ demand, but on her own terms. A disappointing outcome, perhaps, except for the subtle breeze that is heard, as winds begin to blow. It left me wondering if anyone actually wins when women lose? A question that resonated even more deeply in light of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent overturning of Roe v. Wade. It was a reminder that women pay with their lives when society is unable or refuses to honor them as whole human beings.

The other production of a classic that impressed me was La Tempesta, adapted from Shakespeare by Italian artist Alessandro Serra, who also directed and designed the scenery, costumes, and lighting. This visually stunning production, also presented at the opera house, began in very dim light on a bare black stage with a massive, dark grey, parachute-like balloon flowing from the ceiling, bellowing into giant waves and bubbles, that suddenly dropped at the moment of the shipwreck, as a very playful Ariel wrapped it around herself while taking her orders from Prospero. The costume design was a beautiful mix of contemporary and period styles, impeccably constructed and detailed. Prospero, Ariel, and Miranda were in light grey pantsuits made of slightly shimmery fabric that rendered their outfits simultaneously austere, fluid, and fashionable. The other shipwreck passengers’ costumes were period, colorful, and stunning without being overbearing or excessive. Serra leaned into the play’s commedia dell’arte roots, amplifying its masque and clown elements. Trinculo and Stephano, in true Arlecchino and Brighella fashion, delivered hilarious lazzis. At the end of Act IV, these two, along with Caliban, began by walking onstage in underwear; a costume rack was slowly flown in from the ceiling, as the three danced around the rack and helped themselves to an excess of costume choices. They disappeared, and then a tall narrow shaft of light shone upstage, revealing the full court as spirits in ostentatious costumes. It was a bizarre yet absolutely gorgeous scene, and it is eternally etched in my mind.

Otherwise La Tempesta followed the basic plot and was performed entirely in Italian (with French surtitles), except for Caliban’s final line, which was spoken in English and formed as a question (I think): “Was I a fool to take this drunkard for a god and worship this dull fool?” Possibly a message to both the U.S. and the U.K. in our choice of leadership.

The most ambitious and awe-inspiring production I saw in the festival was Le Moine Noir, based on the short story The Black Monk by Anton Chekhov, directed by celebrated Russian artist Kirill Serebrennikov. It was performed in German, English, and Russian by a cast of 22, who exhibited mastery in choral singing, movement, and dance, which only intensified over the course of the nearly three-hour performance at the 13-century Palais des Papes’s beautiful courtyard. The story of a young scholar suffering from delusions of grandeur was told in four parts, each amplifying a different aspect or perspective of the story. The scenic design, also by Serebrennikov, included three cabins, their wooden skeletons covered in transparent plastic, a giant disc which was later revealed to hide an additional three progressively smaller discs, and projections. There was a piano, several benches, and minimal flowers/greenery, brought on and off to shift the space of the garden where the young scholar takes refuge during his illness.

The show involved three iterations of the same basic story: A young scholar, who has been having hallucinations in which a monk dressed in black tells him he’s a genius chosen by God, visits the countryside where an old gardener tells him he should marry his daughter, Tanya. At first the scholar laughs off this offer, then gradually falls in love with Tanya and the idyllic country life, only to become ill and die a tragic death. Each time in Serebrennikov’s production, the story was told in a different rhythm and language, and with different emphases; in the third repetition, told in Russian, the monk’s speeches took on a despotic aura, and the young scholar’s death was made all the more devastating by the strength of his resistance and intellectual agility. It might be easy to assume that the self-aggrandizing scholar has a reference point in Putin. But in an interview, Serebrennikov explained that he chose to tell this story with three different actors speaking different languages to place the story in a diverse world with multiple perspectives, and to emphasize the universality of the scholar’s experience.

In the transition to a fourth scene, the ensemble moved the cabins to the sides of the stage, making room for an exquisite dance of monks in black robes, a la whirling dervishes, while a smaller group of the ensemble harmonized in Gregorian chant-style choral singing. The scene was breathtaking in its choreography, musical arrangement, and staging. The sheer energy it took to carry on a demanding performance like this was mind-boggling to me. I was in awe of this diverse and virtuosic ensemble. At the end of the performance, the audience rose in enthusiastic standing ovation and applauded for what felt like over 10 curtain calls. It was past 1 a.m.

The main reason for my attending the festival this year was the significant inclusion of artists of Middle Eastern heritage; nine out of the 41 shows in the main program were by Middle Eastern artists. I have never seen a theatre festival outside of the Middle East dedicate that kind of visibility to the region. I was particularly interested in seeing fellow Iranian artist Amir Reza Koohestani’s show En Transit, which had received a lot of early publicity. Based on Anna Seghers’s novel Transit, the play places the heroine, a Jewish woman fleeing the German occupation of France, and a contemporary Iranian artist traveling to Chile for a show at the same transit terminal in Marseilles. The two stories are linked by the same interrogating officer and the same volunteer legal assistant. The time warp in the play was matched by the intransigent bureaucratic labyrinth reflected in the production’s Kafkaesque design, housed in an austere light grey stage with two cubicles on either side and an interrogation table in the center. Strategically placed cameras captured the tension and helplessness of the travelers, whose faces were projected on the whole of the upstage wall, engulfing the characters in one another’s’ misery and making it impossible for the audience to look away.

Koohestani developed this piece, inspired by his own experience of being held in the transit terminal of the Munich airport. He had just completed a show at a major German theatre about immigration and was on his way to Chile for another production when he was held at the border and questioned about overstaying his visa. The experience reminded him of Seghers’s novel and the similarity of his situation to the refugees fleeing Europe during WWII. At the roundtable organized by Amnesty International, Koohestani noted that during WWII the government of Mexico processed 88,000 refugees, essentially saving them from certain death. But today governments in Europe and the U.S. are busy erecting endless bureaucratic obstacles, even for a visiting artist contracted by a national theatre. Indeed, Koohestani said he was surprised that German border patrols had not even heard of the national theatre that hosted him in Munich. He realized that theatre artists and audiences exist in a bubble and that theatre doesn’t actually impact policy. He wondered out loud if seeing theatre should be required training for border patrols. Might that change their view, and possibly improve their attitude toward people crossing the border?

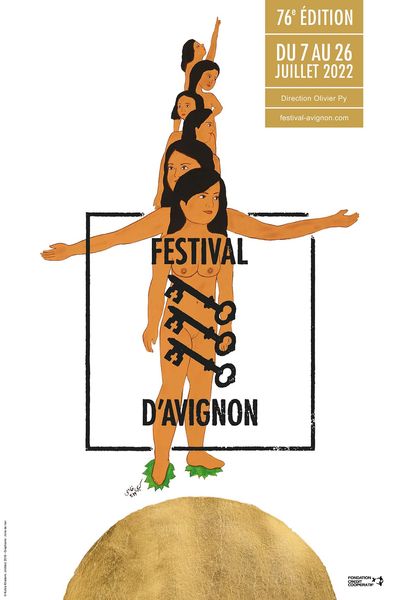

The other Middle Eastern artist on the Amnesty International roundtable was Kubra Khademi. Known mainly as a performance artist, Khademi fled Afghanistan in 2015 and settled in France, where she was awarded a Chevalier d’Ordre des Arts et Letter by the French Ministry of Culture. Khademi’s artwork, selected as the Festival’s key art, depicts six naked women standing in a straight line in a neutral stance, the first one standing on two green leaves, the second one extending her arms out, the last one pointing to the sky. They each look in a different direction and are situated above a golden dome. According to the program information, Khademi’s representation of nudity is not sexualized, but rather a natural depiction of the female body. She also incorporates elements of classical miniature painting in her work, reclaiming mythic narratives dominated by the patriarchy by placing female bodies within iconic imagery.

Various configurations of the same female bodies, battling a dragon or holding a Kalashnikov, are included in Khademi’s exhibit at Collection Lambert under the title “First But Not Last Time in America.” The exhibit also includes photographs and video from the series, “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Hot Season,” created in collaboration with American artist, Daniel Pettrow. In the video, Khademi represents a Taliban fighter, and Pettrow an American politician. In side-by-side split screen, the two dress, Khademi wrapping her turban and Pettrow shaving and putting on a shirt and tie. The photographs include large images of their passports and collages of the two artists in character holding hands in one image, and reaching for one another’s crotch in another. The collection is a damning and critical representation of the U.S.-Afghanistan relationship, and Khademi did not hold back at the interview programmed by Arte in their Artistes en Resistance series, where her video Armor was shown. It shows Khademi walking the streets of Kabul in custom-made medieval metallic armor which emphasized her breasts and buttocks. The performance was intended to highlight the daily harassment Afghan women experience, but it resulted in Khademi being forced to leave Afghanistan due to the threats and harassment she received following it. Khademi, like many Middle Eastern women artists, walks a tightrope of simultaneously criticizing the oppression in her homeland and the global power dynamics that sustain it.

Another Middle Eastern woman artist featured in the main program of the festival was Hanane Hajj Ali, performing Jogging, a piece that earned Hajj Ali the Prize for Best Actor at Edinburgh Fringe in 2017. As the audience took our seats in Theatre Benoit XII, Hajj Ali, dressed in black and reclining in a square of light on the black stage, was stretching and warming up. She took a sip of water, and the gurgling sounds became louder; the audience quieted down and the show had begun. Hanane began to jog within her small square of light. Her breathing filled the theatre. She introduced herself as a 50-something woman, a citizen of Beirut, a cool hijabi who married a genius director and who starts her day by jogging in the streets of Beirut. Her tone was upbeat and fun as she told us that she copes with everything that goes wrong, including a pigeon shitting on her head, by thinking about all the great roles, especially the Greek classics. Medea came up, and Hajj Ali confessed that she once thought of killing her 7-year-old son to end his suffering when he was diagnosed with cancer. Fortunately, he was successfully treated, but the experience led her to research other Medea-like cases in Lebanon, specifically the stories of Yvonne and Zahra. As we learned bits and pieces of their tales, Hajj Ali deftly used disarming humor and subversive audience participation to situate the viewer within these women’s person stories.

Performed mainly in Arabic, with English and French surtitles, the show highlighted Hajj Ali’s impressive versatility and stamina, as her breathing guided us through the emotional journey of the play, almost cradling us in what felt like a generous and necessary maternal act to protect us from the harsh realities described in the play. We were invited to understand a woman citizen’s frustrations in a misogynistic and corrupt country. The piece ended with an adaptation of a poem by Warsan Shire, with the closing line: “No one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear saying, Leave, run away from me now, I don’t know what I have become, but I know that anywhere is safer than here.”

Poetry was the main offering in Shaeirat by Henri Jules Julien. This two-part, four-hour program featured poets Carol Sansour and Asmaa Azaizeh (Palestine), Rasha Omran (Egypt), and Soukaina Habiballah (Morocco) performing their own writing, some alone, some accompanied by another performer and/or projections. I was delighted to see poetry performance programmed in a theatre festival. Historically, poetry was performed throughout the Middle East, and to this day it is among the most cherished art forms in the region.

I would like to close by touching on a very special Off Avignon production I saw, Les Perses (The Persians) by Aeschylus, directed by Tilemachos Moudatsakis, in a production from Crete. Performed in Greek with French surtitles, the show had a cast of three men and one woman portraying the chorus, as well as the messenger Atossa, the Queen Mother, the late king Darius, and Xerxes, the current king who wages war against Greece. The performance was physically demanding and emotionally intense. The men represented the battle scenes in tight, sequential tableaux, moving energetically between the chorus passages and representing specific characters. Atossa’s monologue describing her dreamt premonition of the defeat to come was moving and intense. The messenger’s description of the battle scenes and the extent of destruction brought on by the Greeks was heartbreaking, making one wonder how anyone could ever engage in war again after hearing it. The lyrical sections of the text were delivered beautifully as songs, some sounding to me like Greek folk songs. The costume design was simple but creative and distinct, recycled jeans with character-specific color patches, and in Atossa’s case, rhinestones. There was no other scenery or props.

As I sat there, an Iranian, a Persian, I marveled at the commitment of this Greek troupe to tell this sobering tale of war and its violent execution. It was a cautionary tale, I believe. As the Greek language filled me, I was transported to the ancient theatre of Epidurus, and I imagined Aeschylus’s original audience and their response to this harsh reflection of their nation’s ability to destroy another nation. I was reminded of the power of live performance to communicate the human condition on a visceral level, regardless of the actual language spoken. I was reminded that for millennia, theatre artists have challenged their audience to critique their leaders and empathize with their so-called enemies. And I appreciated, so very deeply, the opportunity to be in community with artists from the far corners of the earth. I felt a part of a global community that has thrived for centuries and is an invaluable contributor to a living world culture. I felt at home.

Torange Yeghiazarian (she/her) is a playwright and director who served as the founding artistic director of Golden Thread Productions, the first American theatre company focused on the Middle East.