Just 24 hours after Beanie Feldstein announced her departure from Funny Girl, American Jewish theatremakers Emma Jude Harris and Gabrielle Hoyt met in person for the first time. 3,000 words, 10 oat milk lattes, and one last-minute Broadway trip later, their resultant dialogue touches on questions of Jewish identity, race, gender, American stories abroad, and the power of Barbra.

GABRIELLE HOYT: Hello, gorgeous.

EMMA JUDE HARRIS: We’re kibitzing!

GABRIELLE: Today we’re discussing Jewish bodies in theatre.

EMMA: And our own Jewish bodies have intersected—finally!—just in time for Funny Girl to explode the internet.

GABRIELLE: We originally wanted to address (via transatlantic dialogue) an op-ed published last month in The New York Times by Pamela Paul titled “Let Actors Act.” In the piece—which also set theatre Twitter aflame—Paul cites Adrian Lester’s performance in the critically acclaimed U.K. import The Lehman Trilogy. Praising the performance of Lester, a Black British actor, in a series of Jewish roles, Paul attempts to argue that actors should be allowed “to portray people who are not like themselves.” The article implies (in classic bad-faith-free-speech-screed fashion) that actors have, in 2022, been discouraged from or even “lambasted” for doing so. Of course, using the agency-free passive voice (who’s doing the lambasting, Pamela?), Paul avoids assigning her strawman an identity. Instead, as she is wont to do (I’d cite her recent columns but I don’t want to give her the clicks), Paul implies that the art of acting is under attack from a faceless menace, ending her article with a horrendously condescending (and wrong), “Bravo to Adrian Lester, who makes you forget the color of his skin, his nationality and his religion—and gives himself over entirely to his performance.” Oy!

EMMA: It’s both bizarre and highly indicative of Paul’s trademark lack of rigor that she picked The Lehman Trilogy as her non-problematic supposed problem play. Given the U.K. theatre industry’s egregious track record of erasing Jewish cast and creatives from Jewish stories, Lehman Trilogy has actually been fairly diligent about Jewish representation: The production has a Jewish director (Sam Mendes) and a rabbinical consultant, and Jewish actor Adam Godley playing one of the three titular German Jewish immigrant brothers both on the West End and on Broadway. As an American Jew living in London who has been involved in calling out several antisemitism scandals in UK theatre, I think these stats pass muster.

The play does have an issue regarding identity and representation, but it is not the casting of gentile actors as Jewish characters that is problematic (or non-problematic, as Paul would have it), but rather how the piece “profoundly underplays” the Lehman brothers’ relationship to and complicity in slavery in their financial beginnings in the antebellum South. Questions created by Lester’s casting coalesce not around his non-Jewishness but around his Blackness—the very quality that, according to Paul, Lester’s acting prowess supposedly negates. (It’s worth noting, too, that while Lester happens not to be Jewish, Paul’s argument effectively erases the existence of Black Jews.) Lester’s onstage presence Hamilton-s the text (I use Hamilton as a verb here to refer to the practice of erasing a history of anti-Blackness, specifically chattel slavery, using Black and brown cast members’ bodies revisionistically). The casting choice, at best, nods to the fact that the Lehman brothers enslaved Black people, gesturing to this part of their narrative without bothering to build a nuanced interrogation into the playtext. At worst, it offers theatrical cover for historical crime.

GABRIELLE: One reason for the creators’ reluctance to address this issue seems pretty clear to me. The Lehman Trilogy centers a Jewish family amassing power and influence within the U.S., a tricky subject, and one that automatically invites accusations of antisemitism. Its creative team, composed of Stefano Massini, Ben Power, and Sam Mendes (of the three, only Mendes is Jewish), has not shied away from that portrayal, characterizing the play as a “parable of American capitalism.” Unfortunately—as is so often the case with such origin stories—The Lehman Trilogy doesn’t account for the fact that enslavement provided the foundation for said American capitalism. The original Lehmans were Jewish; they also enslaved people. Casting Lester means that a Black British man plays a German American Jewish man who enslaved Black people and profited from that enslavement. But the play, originally cast with three white British actors playing multiple roles, makes no move to address this issue, despite the resonances of Lester’s casting.

EMMA: The creative team has seemed overly eager to prove they are qualified to tell this Jewish story. In interviews, adaptor and translator Ben Power has described feeling like an “outsider” in the rehearsal room as a “non-Jew, non-American” (apparently being an Anglican white English man helped him understand the Lehman brothers’ experiences as German Jewish emigrants to America?). Playwright Stefano Massini often refers obliquely to his own “background in the Jewish faith,” rarely bothering to specify that he is not, in fact, Jewish, but rather an Italian Roman Catholic whose father saved a Jewish worker at his factory, earning the young Massini free admission to a Jewish school as a result. Clearly, these artists want to combat any charges of appropriating Jewish narratives, but they’ve failed to examine the historical erasure they’re perpetrating within their work.

GABRIELLE: I can’t believe that we’re putting this piece in conversation with Funny Girl, given how tonally and stylistically different they are—but similar issues arise! And they’re both U.K. imports…which I didn’t even know until you told me.

EMMA: Yes! Producer Sonia Friedman and director Michael Mayer (both Jewish, but who’s counting?) transferred their London revival of Funny Girl to Broadway this year, but the production originally premiered at the Menier Chocolate Factory in 2015. It starred Sheridan Smith, who is decidedly not Jewish, was well known for her West End turn as Elle Woods, another powerhouse role written by men for women to ruin their voices on. Her similarly non-Jewish understudy Natasha J. Barnes infamously went on regularly due to Smith’s frequent indispositions, and the two formally shared the role on the national UK tour in 2017.

The announcement of Beanie Feldstein’s casting for the Broadway transfer was met with jubilant, expectant discourse about the significance of a fat, queer, Jewish woman playing Fanny (along with wannabe Streisand heir Lea Michele’s name trending, due to the perceived snub). But less than a year later, Feldstein shared via Instagram that she was leaving the production months earlier than planned. The time between these two events was characterized by gossip about Beanie’s voice; a mixture of tepid, scathing, and sexist reviews; declining sales and frequent unexplained Beanie absences.

This mishigas is in keeping with Funny Girl’s grand tradition of rumors, flops, near misses, and perennial casting drama. The unofficial U.K./U.S. “Fanny Parade” that led to this moment consists of the following women, some of whom are Jewish, some of whom are vocally qualified, some of whom are actually funny, some of whom are the right age for the casting, and none of whom are all of the above (excepting OG Barbra, of course—more on her later). The Fanny Parade is as follows: Lauren Ambrose (neither Jewish nor vocally appropriate), who was rumored to be attached to a 2011 Bartlet Sher Broadway production that was scrapped entirely after losing its funding; in the U.K., the aforementioned Sheridan Smith and understudy Natasha J Barnes; Idina Menzel, who in 2020 was reportedly in talks to star in Mayer’s Broadway transfer despite being 28 years older than Barbra when she originated the role; Beanie Feldstein, a funny, lovable Jewish actor and sophomore Broadway performer who got the part, despite not being able to sing it; Julie Benko (also Jewish), her acclaimed standby; and finally Lea Michele, an unfunny practicing Catholic with Jewish heritage, initially spurned from the Broadway transfer despite seven years of cosplaying as Fanny Brice fanatic Rachel Berry on Glee, who has now, despite serial allegations of horrible behavior, emerged as the one Fanny to rule them all, proving that the Ryan Murphy Cinematic Universe is in fact our reality.

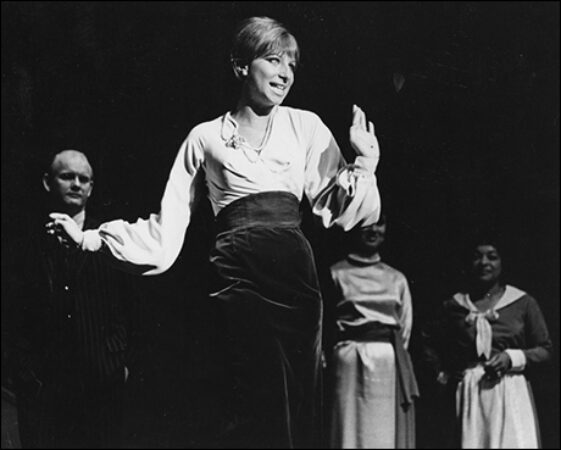

GABRIELLE: What hits me hardest—having just seen the show, and of course having obsessively followed the drama weeks now—is how tremendously disempowering this feels. Barbra Streisand famously took on the role of Fanny Brice at 21. Jule Styne, who had considered Mary Martin and Carol Burnett for the role, described her as looking like a “Cossack” in her audition. But by age 26 she’d delivered an iconic performance onstage and on screen, conducted an affair with co-star Omar Sharif that became an international incident, and accepted an Academy Award while wearing a see-through matching pants set. Though much of the coverage she received at the time contained misogyny and antisemitism, both covert and overt, there’s no denying the power she gained from the role or the control she exerted over her own image.

EMMA: The great commercial hits of the Broadway canon rarely intersect with explicit Jewishness, and even more rarely do we find positive portrayals of explicitly Jewish women. Babs’ arc as she became the greatest star mirrored that of the figure she was embodying, Jewish comic Fanny Brice, portrayed in the musical as an impossibly talented Jewish woman who succeeded against the odds because of her talent. Funny Girl became a success because Babs’ extraordinary talent was a direct mirror for Fanny’s. The meta-arc of the show celebrated the impossible success of not one but two genius Jewish women.

I’d like to don my specialty embroidered “American Reform Jew living in the U.K.” yarmulke once more to point out that the plot and themes of Funny Girl are fundamentally anathema to British society: piercing ambition; cultural assimilation; the commercial success of Yiddishkeit; sexual and professional desire; and Jewish contributions to vaudeville, burlesque, and variety shows. In the U.K., the striving that is at the heart of the American dream, the American immigrant experience, and the American musical is viewed as déclassé. Why the producers decided to start the production’s journey in England continues to baffle me, and feels indicative of their lack of actual care for the story they were telling.

GABRIELLE: These points get at the heart of both Funny Girl and Barbra’s success: that striving can be sexy. Brice, as portrayed in Funny Girl, is a try-hard, a workaholic, and a control freak. So, by all accounts, is Streisand. In the show, these traits earn Fanny professional success, personal fulfillment, and (for a while) a smokin’ hot husband. And as for Streisand…again, did I mention the affair with Omar Sharif and the see-through pants set?

Contrast Streisand’s initial success to the fates of Fanny Brice onstage and Beanie Feldstein offstage in 2022. Beanie has been pushed out of the role—humiliatingly so—and even while performing, I would argue that she is never granted the control that Barbra exerted. Part of this is because she can’t sing the part, a fatal blow in a musical where belting chops equal narrative power. But even within the staging, she’s so frequently swallowed by sets, swathed in voluminous costumes, or towered over by her fellow cast members. She’s rarely given the chance to take space and just be funny—a task at which she would have excelled, and in which she would have been able to exert some control over the theatrical world around her.

EMMA: Ironically, given the lack of space that Beanie is afforded in this production, much of the buzz around her casting was predicated on how supposedly empowering the concept of “fat Jewish Fanny” was. This girl-power-fueled hot take ignores the inconvenient truth that Funny Girl is a fundamentally sexist musical about a Jewish woman who can be “funny” or “gorgeous” but certainly not both. Furthermore, the show makes clear that, for funny girls, domestic bliss can’t coexist with stardom. Fanny ends the show successful but alone, bereft of the gorgeous Nicky Arnstein, who made her “feel sort of beautiful” until he didn’t (not to mention absconding with her money). Sure, Fanny ends the show with a spirited reprise of “Don’t Rain On My Parade,” but even this moment of supposed empowerment can’t undo the show’s corrosive, misogynistic message—if you’re good for a laugh, you’re wrong for the guy—blasted out for nearly 3 hours at $100 a pop.

GABRIELLE: In actuality, many of the issues within Funny Girl have nothing to do with Beanie, or with Barbra, for that matter. They have to do with Brice. The show’s book largely glosses over her actual act, and it’s easy to see why. She often performed in blackface and redface, and her Jewish humor contained wildly offensive stereotyping that would never fly today. Even in 1964, the book of Funny Girl softened Fanny’s jagged edges. The 2022 production goes further: In the original Broadway cast, Fanny’s maid, Emma, was played by renowned Black actress Royce Wallace. In the current revival, she’s played by Ephie Aardema, a Fanny understudy who is herself white and Jewish. Meanwhile, the role of Fanny’s Black confidante is taken by the character of Eddie, enlivened by a virtuosic, Tony-nominated performance from Jared Grimes. In the musical, Eddie is not only Fanny’s friend and choreographer; he also pines after her both romantically and professionally, lamenting that “I taught her everything she knows” while she goes onto bigger and better things. Given the complex and troubled legacy of Jewish and Black performers in musical theatre—a legacy that Brice herself embodies!—I found the show’s treatment of Eddie’s race disconcerting, to say the least.

EMMA: In addition to erasing Fanny’s complicity in anti-Blackness, the piece never really deals with her Jewishness beyond the most flippant smattering of additional Yiddish (thanks, Harvey). A “Mazel Tov Fanny” banner written in transliterated English feels like an indicator of this production’s superficial engagement with diasporic 20th-century Ashkenazi Jewish immigrant identity. Funny Girl doesn’t unpack the antisemitism Brice faced, nor does it address the internalized antisemitism she presumably felt: In 1923, sick of being a sight gag, she underwent a “nose bobbing”(rhinoplasty) from a quack doctor in a Baltimore hotel room. Unlike Brice, Babs defiantly refused a nose job, but insisted on being filmed only from the left side.

Beanie, meanwhile, has been the recipient of fatphobic critiques her whole career. Clearly, based on reviews and how she’s been treated, her unruly Jewish body is still not accepted on a Broadway stage. One of the tragedies of this debacle, for me, is how portraying an unconventional-looking, talented, hilarious Jewish character has exposed the unconventional-looking, talented, hilarious Jewish Feldstein to such mistreatment. Regardless of whether or not she can sing the role, her body has been devalued, and neither the producers of Funny Girl nor the script itself reckon with that harm.

GABRIELLE: The common problem in both The Lehman Trilogy and Funny Girl (and again, I cannot believe that I just typed this sentence) is one of silence. They both, at heart, deal with the status of Jews in America. That’s a complex story! Yet the idea seems to be that if you get the “right” kind of people together in a room, you’ve absolved yourself of addressing such complexity. In the case of Lehman, this magical thinking leads to Jewish and Jewish-adjacent creatives deciding not to discuss the Lehman Brothers’ enslavement of Black people…while casting a Black actor in a starring role. As for Funny Girl, a similar mentality leads to casting Beanie Feldstein—a fat, queer, Jewish, wildly appealing performer who cannot sing her role—in a dated piece with a problematic plot, rife with its own elisions. Of course she couldn’t carry the show!

EMMA: In 2022, who could? And why am I positive it’s not going to be Lea Michele?

GABRIELLE: For me, our discussion of these two shows has crystallized why, so often, questions of casting Jewish roles become massive firestorms. With its status as religion-but-also-ethnicity, ethnicity-but-not-quite-race, often-privileged-yet-frequently-persecuted, over-and-under-represented-in-entertainment, Judaism often does not fit within the reductive language and thought processes we use to discuss representation in theatre. There’s a desire, I think, for performers with marginalized experiences to “fix” problematic works and narratives with their mere presence. Because the very concept of a marginalized experience gets complex when attached to Judaism—who gets to claim it, who does not, and what that even means within a specifically American Jewish context—the moral framework frequently attached to representation begins to fall apart. Such a framework relies on the belief that performance, authenticity, identity, and ethics are one and the same—which is false. These concepts are related, but they are not the same. And telling Jewish stories and casting Jewish roles really brings that problem into sharp…profile, let’s say.

EMMA: What you’re really talking about is casting as absolution. And maybe it’s a bit Christian to be aiming for absolution.

Gabrielle Hoyt is a dramaturg, writer, and director. She is pursuing her MFA at Yale. @gabhoyt

Emma Jude Harris is a director and dramaturg who works across forms in opera, new writing, and early modern theatre. She is currently based in London. @HeyEmJude

Ephie Aardema’s name was initially misspelled in this piece.