I was one of more than 700 people who traveled or telecommuted to Pittsburgh for Theatre Communications Group’s 32nd National Conference in June. After three years held at a distance—TCG’s last in-person convening was in Miami in June 2019, with virtual conferences taking place in the summers of 2020 and 2021—this year marked our organization’s first hybrid conference, offering in-person events June 16-18 and virtual programming June 15-17. It was an ambitious four-day undertaking that involved some behind-the-scenes pinch-hitting by volunteers and members of staff. As an attendee and sometime conference worker, both in person and online, I appreciated the patience and fortitude of everyone involved.

It was also my first TCG conference. While I cannot speak to the experience of past conferences, several people told me that the city always sets the tone. I’m not sure if that same sentiment applied to those who tuned in virtually, but I have the City of Bridges to thank for a new perspective on the industry I cover.

The Three Sisters: the “Roberto Clemente” (Sixth Street), the “Andy Warhol”(Seventh Street), and the “Rachel Carson” (Ninth Street) Bridges. (Photo by Michael Baker International)

The August Wilson African American Cultural Center. (Photo by Joshua Franzos Photography)

To me, this year’s conference was about healing, about finding new ways to take care and show up for ourselves, for our work, and for each other. While I would doubt that any shared life-altering epiphany has ever been reached while sitting in upholstered banquet chairs, I mean it when I say that it was genuinely nice to meet everyone and share rooms together, whether behind masks or on Zoom. For an industry still grieving the immeasurable losses of the COVID-19 pandemic while attempting to address the systemic inequities embedded in our practices, I think that the conference provided some much-needed time to consider a way forward together.

Conference programming centered around three arcs: Redefining Our Art, Transforming Our Practices, and Tending to Our People. With sessions focused on subjects such as “Trauma-Informed Theatre: Lessons from Care Work,” “Rethinking the Canon,” “Harm Reduction & Transformative Justice,” “Native Futures Are Our Future: Indigenous Multimedia and VR Artistry,” “Together We Rise: Dream Session for a Queer American Theatre,” and a series of forward-thinking sessions held by TCG’s 2022 Inheritors Curation Team, there were ample opportunities to envision the future of theatre. Following is my day-by-day report of events and conversations, compiled from firsthand experience, videos, and transcripts.

Wednesday, June 15

I arrived in Pittsburgh on the morning of the 15th. My fabulous Uber driver, Garcia, showed me around the area en route to the Westin, recommending local restaurants and wishing me well. This set me up for a productive week. The virtual programming kicked off with a plenary keynote conversation between Pittsburgh icons and Carnegie Mellon alums Tamara Tunie and Billy Porter. Both vouched for the importance of free after-school arts programs as vital to their development.

Billy Porter.

Tamara Tunie.

“I’m the last of a generation of people who had access to things that our government set up to help,” Porter said. “I was grandfathered into benefiting from a government that actually cared about its people.” He marveled at “the arts education that we were exposed to in a public school situation for free,” vividly recalling a three-ring binder bursting with double-sided pages listing after-school activities. These programs gave Porter the opportunity to perform in his first musical alongside 150 classmates; his was the only role not double-cast. For her part, Tunie remembered choosing an instrument and joining the choir in the fourth grade. Both credited high school performing arts teachers with steering them toward the BFA programs at Carnegie Mellon. Tunie also recounted her alienating college audition experience as the only Black person out of 100 applicants trying out for the program.

“This is what we’re talking about when we’re talking about access and opportunity,” Porter said. “I didn’t even know it was there. I didn’t even know Carnegie Mellon had a program like that. I had no idea.” He added, “I wouldn’t be sitting here if somebody hadn’t given me an opportunity.”

Porter struggled throughout his 20s to fit into the limited roles offered to queer actors, often being dismissed as “too flamboyant,” until he realized his originality was in fact his strength.

“Everybody told me that my queerness would be my liability, and everybody was right for decades,” he said. “But in the middle of that journey I chose myself, because I knew that however the chips may fall, wherever this may lead, it’s going to be rooted and based in my authenticity. So let me let all the other stuff go and just simply be in this moment with myself.” He continued, “I was waiting for Clive Davis to discover me. I was waiting for Stephen Sondheim to write something for me. No: Write it for yourself. Do it yourself. Creativity comes from inside you.”

Placing value in his authentic self prepared Porter for the opportunities that would follow, including the roles of Lola in Kinky Boots and Pray Tell in Pose.

With the wisdom of Billy Porter and Tamara Tunie still resonating in the back of my mind, I put on my blazer and went to moderate a discussion on virtual theatre. My session, “Making Virtual Theatre Work: How to Reach Audiences at Home”, featured BroadwayHD founder Bonnie Comley, Geffen Playhouse associate artistic director Amy Levinson, Audible Theater artistic director Kate Navin, Arlekin Players Theatre managing producer Sara Stackhouse, and Ricky & Dana Young-Howze of the Young-Howze Theatre Journal. Panelists shared their pandemic-born innovations and explored the ongoing potential of virtual theatre.

“For us it’s actually about creating a new genre, and I think there’s something interesting there to talk about,” said Stackhouse, whose company in June produced The Orchard, a Chekhov-inspired production incorporating robots, holograms, film production, streaming software, and gaming technology to create an interactive viewer experience. The key, Stackhouse said, is to learn “what tools, ideas, ways of interacting and having meaningful experiences are being used by other industries and other sectors,” and see what talented theatremakers can do “at the cross section of those things.”

Along with this genre-carving practice, though, come the responsibilities of building infrastructure and reaching new audiences.

“The book manuals have not been written yet,” said Ricky Young-Howze of the lack of training for virtual theatre. “There aren’t as many teaching artists [for the virtual medium] as there need to be.” Theatres, he said, also need to think about “who could never come into the theatre because they couldn’t physically access it, economically access it, or socially access it, where they would feel excluded.” The next step, said his partner Dana Young-Howze, after “finding the people who need this,” is “not just creating content for them, but listening to what they want.”

The first day of virtual TCG programming was rounded out by a keynote conversation between activist/policy expert Julian Brave Noisecat and theatre producer/climate justice leader Ronee Penoi. A member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen and a descendant of the Lil’Wat Nation of Mount Currie, Noisecat recognized Native-led movements like Idle No More, the fight against the Keystone XL Pipeline, and the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation for solidifying the connection between Indigenous rights and environmental activism.

Noisecat’s activism begins at the intersection of climate change, environmental advocacy, land occupation, broken treaties, and the marginalization of Indigenous history. He explained that political advocacy depends on the power of a compelling narrative, and movements often fail because of faulty storytelling techniques. In this time of division, he emphasized, it is more important than ever that all communities are fairly represented in media and that their lived experiences are reflected in public policy.

“As an insider in Indigenous storytelling,” said Noisecat, “what I really appreciate is the stuff that gives us visibility on this broader stage, where other people can also read, watch, or listen to our stories, but where I as an insider can also see stories, people, places, and cultural things that I know, that feel intimate to me. As a Native person, that’s a very novel experience in America.”

He highlighted FX’s series Reservation Dogs (created by the Native sketch comedy troupe the 1491s) and the book There, There by Cheyenne and Arapaho author Tommy Orange as impactful examples of Indigenous representation.

I walked away that first day with a lot on my mind. Knowing that it took decades for the industry to shine its light on a star like Billy Porter left me wondering just how much talent we’ve unknowingly relegated to the wings. There’s something to be said about being ahead of one’s time and reclaiming creative control, but there’s still the problem of flawed storytelling. Maybe the lack isn’t in the talent of the actor but in the depth of the character; maybe you’re missing the technology to best equip your artists or the outreach to connect you with an unfamiliar audience. Access happens where there’s an abundance, not a scarcity, of opportunity. It stands to reason that as theatremakers, we are only bound by the environments we create.

“Garrison Canal” by artist Andrea Polli, located at Garrison Place between the 900 block of Liberty Avenue and Exchange Way. These lights are programmed to respond to real-time changes in local weather conditions and are connected to a weather station in Downtown Pittsburgh. (Photo by Alexandra Pierson)

Thursday, June 16

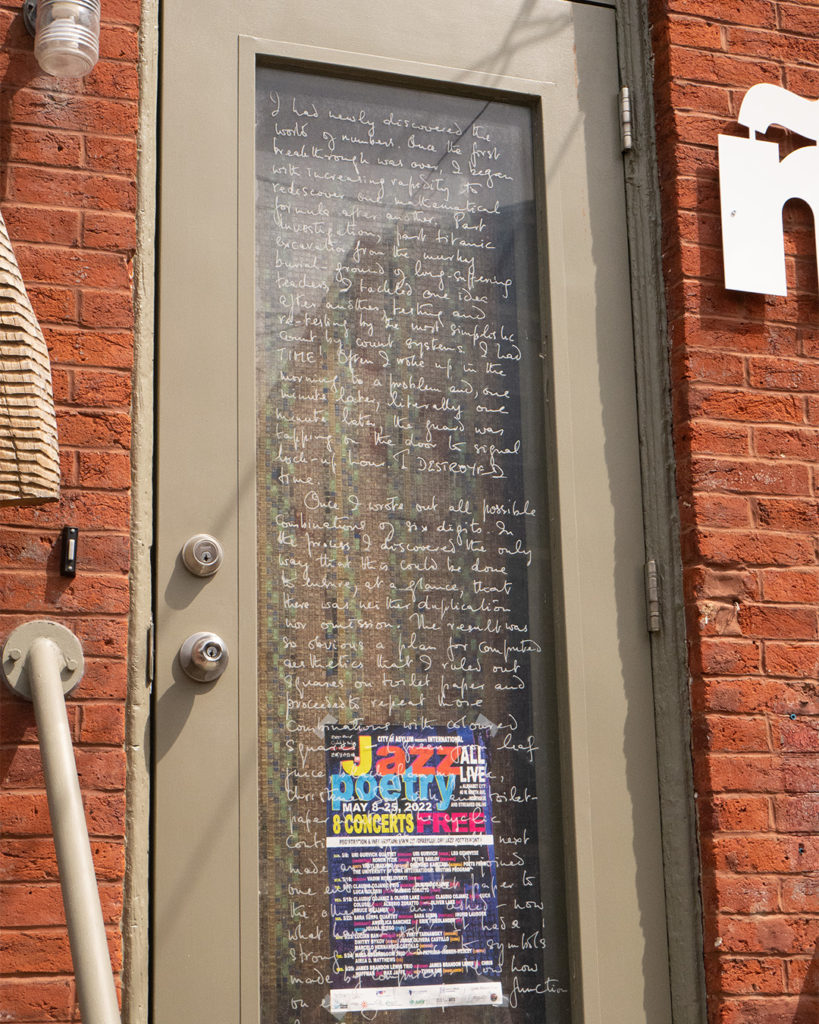

For the conference’s first in-person day, you might say I woke up on Pittsburgh’s Northside, as I hopped on a morning trolley and followed a City of Asylum walking tour down Sampsonia Way. This nonprofit hosts the largest sanctuary residency program in the world for writers living in exile under threat of death, imprisonment, or persecution in their native countries, providing them with three years of free housing, healthcare, and access to social services and resettlement.

Our helpful guide, City of Asylum’s manager of special projects, Erin Roussel, told us all about the program’s history. A member of the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN), City of Asylum welcomed its first writer-in-residence, Huang Xiang, and his wife, Zhang Ling, in 2004. A poet, calligrapher, and advocate for constitutional freedoms during the post-Cultural Revolution period in China, Huang Xiang spent a total of 12 years in prison and labor camps for his work, which was later banned from publication.

Part refuge, part relief, each of the residency homes along Sampsonia Way feature unique, artist-created “house publications,” i.e., literary texts incorporated into their facades as public art. Huang Xiang’s “House Poem” was the first in the series. The buildings currently house five resident writers and one artist. The tour culminated at Alphabet City, Asylum’s bookstore/cultural center/restaurant/performance venue, which has offered free online and in person public programming since 2016.

Back at the Westin, conference programming continued with a hybrid opening plenary featuring the launch of the 2022 State of the Artist study facilitated by Khanisha Foster and Susan V. Booth; the presentation of the Alan Schneider Director Award to Seema Sueko; and a grounding moment led by healing artist Rebecca Kelly G. Positing a series of powerful prompts, such as, “What might theatremaking look like in 2027, and what needs to happen now to get us there?” and “What does your ideal day in the life of an artist look like, and how is that different from your daily life now?,” Foster and Booth garnered a variety of responses from theatremakers from diverse disciplines and communities. Sueko highlighted the potential for playwrights to submit scripts as audio files, reasoning that giving literal voice to a playwright’s language can help us experience their rhythms and intentions.

“How many people sat in their living rooms and decided how to make theatre from here on out?” asked facilitator Khanisha Foster, looking back at the past two years of pandemic and protest. “How many of us have decided we are not going back into a rehearsal room with panic in our bones? That we want the space, and time, and energy, and honoring to do what our body, minds, and spirits are capable of. If we don’t ask now, then when?”

The point seemed clear: that by visualizing the industry we hope to create, we are able to more clearly define the work ahead.

Following the plenary, I made my way to the “Making Home: Contemporary & Devised Performance in Pittsburgh” session with director, performance-maker, and community organizer Lyam B. Gabel and theatre director and educator Adil Mansoor, moderated by Chanel Blanchett, programming manager at Pittsburgh’s Kelly Strayhorn Theater. Taking inspiration from the tradition of Black homemaking, the Strayhorn hopes to engage artists in deconstructing the complicated concepts of home and belonging, striving to be a home for creative experimentation, community dialogue, and collective action rooted in intersectional anti-oppression and the liberation of Black and queer people.

This practice of cultivating belonging is important for Gabel, who lived in New Orleans for eight years before coming to Pittsburgh for graduate school.

“I make a lot of work about archives,” explained Gabel. “I do long processes where I do oral histories and then create performance from those oral histories. Although it’s not strict documentary performance, it’s kind of docu-fiction or docu-fabulation. It’s a hybrid between narrative and documentary work.” Their recent project, the dance floor, the hospital room, and the kitchen table, interweaves 32 oral histories and countless hours of research into an immersive media archive of queer care, stitching together stories from COVID-19 and the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

“Thinking about home and community and all those things, how those networks of care can get built inside of a rehearsal room, have been really important to my practice and also my livelihood as an artist,” Gabel continued. “Theatre has this really incredible ability to create networks of care that can help to sustain us. I think it has to, unfortunately, because it does not sustain us in other ways sometimes, financially, which is something that I know a lot of people are working to remedy. But there is something that I have relied on theatre to do since a very early age, which is to make home and literally sustain me through those networks. That’s now a part of the active process I’m engaged in when I’m making work. It’s not just about what we’re making, but also about the connections that we’re making with one another as we’re making it, and being really intentional about how those things can help to sustain the process.”

For Adil Mansoor, who was raised outside of Chicago and moved to Pittsburgh 12 years ago, his journey involved not only carving a path into the theatre industry, but also finding a sense of home within it.

“When I moved to Pittsburgh, if I’m totally honest, the barrier to access when it came to entering the theatre community here was high,” Mansoor said. “I didn’t know how to enter a theatre. I didn’t study it in undergrad, I wasn’t an actor, I couldn’t afford a free internship, I couldn’t apply for the jobs. I just was like, ‘How do I do this?’” The people who welcomed him, he recalled, were “dancers and silk screen printers and museum workers. So my practice was developed in other disciplines. I knew theatre was where I felt the most alive, that kept being true, but I grew up in other disciplines in Pittsburgh.” At that point in his life, he felt hurt that “the one place I wanted to be, all of the doors were closed,” but now he counts himself grateful for what he’s learned outside the theatre industry. “To have DJs as your sound designers and architects as your set designers teaches you a lot about really figuring out what you’re trying to do,” he said.

Mansoor, whose current play Amm(i)gone is an adaptation of Sophocles’s Antigone that doubles as an apology to and from his mother, credits Karla Boos, artistic director of Pittsburgh’s Quantum Theatre, for giving him his start. Both Mansoor and Gabel agree that Pittsburgh has a unique infrastructure in place to support new work.

“Something that’s really incredible to me about the Pittsburgh arts community,” said Gabel, “is that there are resources here for artists making work, which is not true everywhere. Getting to experience that has been really transformative for my practice. Not that I did not have any access to resources, but in New Orleans a lot of the access to resources come from national funding organizations, and in Pittsburgh there’s a robust local funding and foundation network. That is something that feels really unique to the ecosystem here.”

Mansoor concurred, pointing to the support the Strayhorn and the New Hazlett have given to emerging Pittsburgh creators in various disciplines, in particular Strayhorn’s Freshworks residency program and the New Hazlett’s Community Supported Art (CSA) performance series as lifelines to the field, and lauding innovative Strayhorn programming director Ben Pryor.

There is certainly no shortage of new ideas brewing in Pittsburgh, and both Mansoor and Gabel want the field to recognize that theatre can thrive outside of New York.

“It feels like a lot of times in order to get credibility you have to leave,” said Gabel, “that your work has to be seen somewhere else and then it’s credible. It’s really transformative when our leaders start looking in their own backyards and being like, ‘Who’s here? Who’s doing something interesting?’ Maybe they haven’t shown something in New York, but that doesn’t actually mean, especially with the right support, that they couldn’t be making really amazing things.”

But all work and no play makes for dull theatre, and Mansoor rightly said that after a difficult few years, it is time to start the healing process. Speaking of the fatigue and despair of many of his friends and colleagues in the field, Mansoor said he felt the urgent need “to figure out what we can do to instigate joy, even if it’s just tomorrow or next week or next year. It feels like a really big puzzle. I want to keep making this work. I want to keep making it with you all. I would really like to have joy while we do this very, very hard job. So what are the ways to center joy and care without shifting away from rigor? I don’t think those words are the opposite of rigor at all. I actually think they’re intrinsically the same or connected.

“As a field, how do we find joyful rigor?”

In the spirit of instigating joy, I grabbed dinner from Condado Tacos and headed over to the opening night party at the Mattress Factory, thrown by the Pittsburgh host committee.

Thursday was certainly a busy day, but when things finally slowed down, I found myself reflecting on concepts like home, sanctuary, and joyful rigor. For the residents of City of Asylum, the program provides very real artistic refuge and personal safety. At the same time, I considered whether theatre could be a place of sanctuary for us. For members of a weary and weathered field, whose spaces often no longer look like home, how might we visualize our sanctuary? I could definitely use more joyful rigor in my day, and if there’s one thing I’ve taken from my time in Pittsburgh, it’s the idea that a better way is possible.

Friday, June 17

At the session “Race and Intimacy for Artists, Management, and Administrators: What to Know,” educator, activist, actor, director, and intimacy coordinator Kaja Dunn explained that she’s not just on hand for combat choreography or steamy scenes; in fact the true role of the intimacy coordinator is to prevent harm, both physical and emotional. No cast member, she said, should be asked to comply with unwanted physical contact or violate their bodily autonomy for a performance. In particular to safeguard cast members of color, LGBTQ+ performers, young performers, disabled performers, and other underrepresented theatremakers on sets or stages, Dunn emphasized that rehearsals should have an intimacy coordinator. If a script deals with harmful cultural stereotypes or requires young actors to kiss, an intimacy coordinator can step in, ask questions, and establish boundaries.

“You cannot colorblind choreograph,” said Dunn. Nor should theatres skimp on other culturally specific services: If they are going to cast more diverse performers, they need to make space. This means providing a hairstylist who regularly works with different hair textures, makeup that matches cast members’ skin tones, and a wig budget, if required. If performers are expected to supply their own foundation or braid their own hair, theatres should compensate them for those costs.

Harm can be done in more subtle but insidious ways in the rehearsal room; Dunn advised theatremakers to ask, “Are you using people’s cultural knowledge and capital without compensation?”

Wali Jamal, Justin Emeka, E.G. Bailey, and Sha Cage. (Photo by Kitoko Chargois)

Caroline B. Jackson Smith and Wali Jamal. (Photo By Kitoko Chargois)

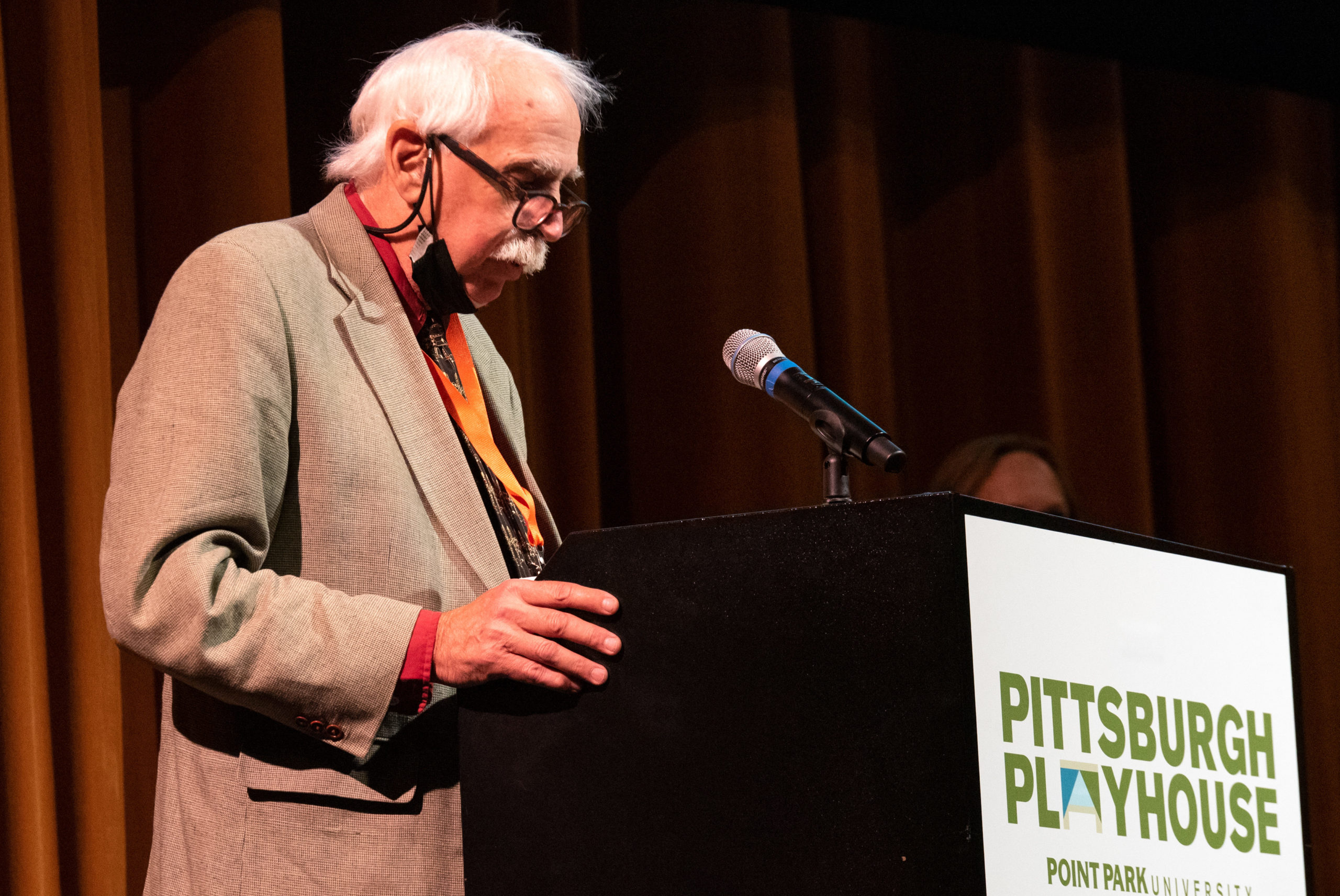

The conference coincided with Juneteenth or African American Emancipation Day, the U.S. federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery under General Order No. 3 on June 19, 1865. A special session, “The Meaning of Juneteenth and August Wilson’s 100-year Journey to Freedom,” was held at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center across the street from the Westin, featuring E.G. Baily, Justin Emeka, Sha Cage, Wali Jamal, and Caroline B. Jackson Smith. At the time of the conference, a production of Two Trains Running was playing at the Pittsburgh Public Theatre, directed by Emeka, who also played the role of Holloway alongside Jamal, who played the show’s punctilious undertaker, West.

Jamal has the unique credit of being the only actor in the world to have appeared in all 11 of August Wilson’s plays, including not only 10-play American Century Cycle but also the autobiographical solo show How I Learned What I Learned.

“What immediately affects me about August Wilson, what the legacy of August Wilson means to me primarily, is opportunity,” said Jamal. “I didn’t get into theatre until I was in my late 30s. I always wanted to be in it. I always did. When I was going to Carrick High School, I wanted to take theatre. They told me I couldn’t take drama because there wouldn’t be any parts for me. It was pretty much right, but that was before August. Now almost any high school kid can have an opportunity to experience theatre and portray characters that represent them clearly, respectfully, and truthfully.”

While Wilson created an indelible collection of roles for Black actors, and helped employ a generation or two of great Black actors, including Samuel L. Jackson, Denzel Washington, and Viola Davis, Emeka noted, perhaps paradoxically, that “a lot of Black people don’t feel like they have a right to August Wilson because they can’t speak that way, or they don’t have that authentic of a ‘Black experience.’ I’m interested in empowering the next generation of Black actors to find themselves through the work without trying to be Anthony Chisholm or Stephen McKinley Henderson. They’re beautiful, but you don’t have to be them in order to do August Wilson.”

At the same time, Emeka clarified, it is not enough for theatres to just stage August Wilson’s plays and repeatedly use the N-word, as his plays do, without context. There needs to be an acknowledgment of the history and legacy involved. It is important to “set the work up right,” he said, as a holistic experience for the audience.

Even Wilson himself expressed the need for his plays to be staged with a certain cultural reverence. There were theatres he would return to and places he would never work again. Advocating for artistic control was a central part of Wilson’s playwriting journey.

As Oberlin College theatre department chair Caroline B. Jackson Smith explained, “After the first couple of plays suffered with white producers, they went to a different model of producing, and it had to do with partnering with other regional theatres so that they built their way to Broadway as their own producers. They had to select which regional theatres would be able to do the work in the responsible way that it was being crafted.”

No one would deny how hard Wilson worked to tell stories and bring his characters to life. The freedom to express oneself can also feel like a burden, though, as the ambition to influence and advocate requires a tremendous amount of effort.

“I think that’s what the tie-in between August and Juneteenth means for us now,” Jamal explained. “In his plays it’s always, always stressed that you’ve got to work, that freedom comes with work. All freedom means is that now we’re going to work. We’ve been working for 300 years, but now we can work for ourselves. That’s what it’s all about.”

He quoted Two Trains Running: “Freedom is heavy. You got to put your shoulder to freedom. Put your shoulder to it and hope your back hold up.”

Across the street in the Westin’s Allegheny ballroom, a hybrid plenary with remarks from elected officials, followed by a legacy conversation with the members of SITI Company, was already underway.

As the first Black mayor in Pittsburgh’s history, Ed Gainey offered his thoughts on how to bring communities together.

“Arts and culture changes lives,” Gainey said. “That’s the power of art. That’s the power of theatre. That you can express how we should be living, what life should be. Through arts and culture we begin to know one another, we begin to respect one another, and when that happens we eliminate racism.”

He spoke about the importance of arts education and his desire for arts funding to serve as an investment in Pittsburgh’s future.

“When I took office, because this city has often been siloed and segregated, I wanted to change how people see this city,” Gainey said. He and his wife Michelle created the Pittsburgh Paints initiative, which celebrates local artists from different cultures with a monthly rotating art exhibit in the mayor’s executive conference room. “I turned my conference room into a canvas room for the whole city to be educated,” Gainey said.

For their part, SITI Company, now in the midst of their final season, were led in a virtual colloquy from their frequent base in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., by frequent collaborator Jessica Hanna, looking back on decades of not only making essential, ensemble-created theatre works but forging an influential training aesthetic inspired in part by their work with Japanese theatremaker Tadashi Suzuki. As founding member Ellen Lauren put it, “Plays are what a company does, but they’re not what make a company.” And her colleague Steven Webber chimed in, in bittersweet past tense: “We were not employees of an institution. The company was our bodies; it was us.”

The long day of reflection concluded with the Vibes N’At Pittsburgh BIPOC Artist Celebration hosted by TCG and the Kelly Strayhorn Theater at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center. The lineup included performances by Geña y Peña, Mai Khoi, #notwhitecollective, Alumni Theatre Company, Mita Ghosal, Jacquea Mae, and DJ Samira Mendoza.

Friday proved to be a great day for listening and expressing gratitude. Pittsburgh provided an excellent backdrop to examine history, from honoring the legacy of August Wilson to recognizing the city’s first Black mayor. There’s a lot of conversation happening right now around EDI initiatives and addressing systemic injustices in theatre, but it’s not often that we get to hear from the people on the front lines of that advocacy. Wilson paved one road to change, and that was only the beginning. It’s also important that creative teams consider the expertise of intimacy coordinators and sensitivity readers to avoid harm. And when harm occurs, procedures need to be in place to address it. Every theatre should strive to be a place playwrights want to revisit, not regret.

Saturday, June 18

I started my last day co-hosting a live version of AT’s Offscript podcast, featuring longtime arts journalist Sharon Eberson, City Theatre co-artistic director Monteze Freeland, and Quantum Theatre artistic director Karla Boos.

As for what sets Pittsburgh apart from the art scenes in other cities, both directors agreed that there is a strong network of support for artists.

“The theatre community here is loyal,” said Freeland, who came to the city from Baltimore. “It’s rich, it’s full of life and support. It opens and holds the door open for new people. You hear a lot of times in other cities that people have a hard time breaking in. I think we actually embrace new artists here in Pittsburgh. When they get here, we’re excited about their talent, we’re excited about what they can bring to our community, and we hold those doors open. Of course, there’s more work to do, but we have a breadth of theatre that allows for that to happen on many different levels.”

Boos echoed the sentiment, saying that this openness is especially true of mid-size performance companies. She described from personal experience how August Wilson, a Pittsburgh native who mostly didn’t live or work in his hometown in his adulthood, nevertheless fostered a legacy of good will there.

“We are all, in the present theatre, the spiritual brothers and sisters of August Wilson,” said Boos. “In 1990, when I was incredibly young and wanted to start a theatre in Pittsburgh, I sought out August Wilson, found him in the Crawford Grill, and talked to him about my idea to start a theatre. I was no one from nowhere, and that man extended his generous spirit. It was instrumental. Monteze is not kidding when he says we have had a tradition of embracing people for, in my experience, 30 years. And we love our differences. We love a kind of collegiality that makes all boats rise.”

Though Pittsburgh’s arts community is strong, there is still work to be done toward making theatres accessible, inclusive, and anti-racist. Freeland emphasized the key difference between words and actions when it comes to organizational change. While many theatres shared messages of support in response to Black Lives Matter and We See You, White American Theatre, he advised us all to pay attention to which theatres are driving change from within.

“Sometimes you have to clean up inside of your house before you can open the door and invite people in,” said Freeland. “At least that’s how I was raised. So I think there’s value in that and there’s a purpose in that. We should be looking at those companies who are inside actually doing that work from the ground up, and making sure that those who are coming into your own spaces know that work is happening.”

He pointed to Pittsburgh Playwrights’ Ground Up Theatre training program, which provides free theatre training for people of color in Pittsburgh to address disparities in industry education and hiring practices, while ensuring that diverse candidates are set up for success. He stressed that making sustainable theatre in Pittsburgh requires engaging with all the layers of a community. This means partnering with local restaurants, organizations, and community kitchens, uplifting residents of color through opportunity, and creating safe environments where people are valued.

My conference experience ended with a canceled flight, which gave me a few more hours in the Steel City. I was fortunate enough to spend that time at the Forbes Tavern toasting the legacy of Terry Nemeth, who will retire this fall after nearly 40 years as the publisher of TCG Books and American Theatre, and who was the subject of a heartfelt farewell tribute at the conference’s closing plenary.

As a long champion of Wilson’s work (TCG Books helped realize the playwright’s dream of publishing the entire Century Cycle), the tribute to Nemeth provided a fitting capstone for a conference which both honored and contextualized the good work of the past, as well as learned from those improving the field.

Can theatre heal itself, and might it heal us? Gathering together last month in Pittsburgh felt like a pretty good start.

Alexandra Pierson (she/her) is associate editor of American Theatre. apierson@tcg.org