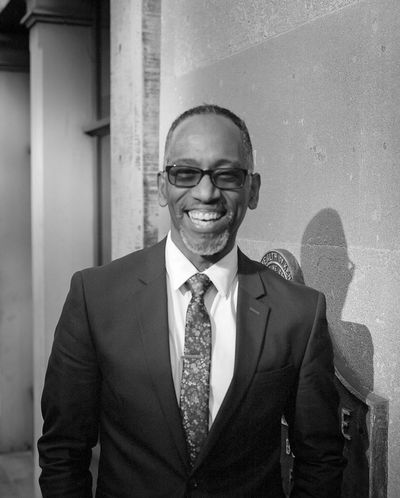

“We have not yet announced the death knell of the Humana Festival,” Robert Barry Fleming insisted to me in a wide-ranging interview last month. The artistic director of Actors Theatre of Louisville, Fleming started at the job in the summer of 2019, and less than a year later, like theatre leaders everywhere, he found himself shepherding his organization through unforeseen existential crises due to COVID-19 and the racial justice protests of 2020.

Among the challenges unique to his position: While Actors Theatre is a year-round regional theatre with a full season for audiences in northern Kentucky and southern Indiana, since the late 1970s it has been known outside Kentucky primarily as the home of the annual Humana Festival of New American Plays, an incubator of acclaimed playwrights and plays that also served as a social gathering for theatremakers and critics from all over the U.S. and the world. What most of these happy attendees didn’t know or care to think much about was that the festival ran on the no- or low-wage labor of a large company of young apprentices, pressed into service to help mount as many as six full productions in a few months. The learning and networking opportunities of this program were undeniable, but so was the exploitation, and the pernicious privileging of those who could afford to work for so long for so little.

What most of us also didn’t know: The support of the Humana Foundation, which underwrote the festival bearing its name since the early 1980s, was not locked in forever but had to be renegotiated every few years, and the foundation appointed a new CEO, Tiffany Benjamin, last December. And so, with both the status of the apprentice company and the nature of Humana’s support in question, no festival was planned for spring 2022 (the theatre hosted a virtual exhibition of new plays in 2021 after skipping 2020 due to the pandemic). When the festival’s non-occurrence became clear earlier this year, Stephanie Wolf, a journalist at WFPL in Louisville, wrote a widely circulated piece announcing this as news, though Actors Theatre had not put out a release. In our recent chat, Fleming told me that a long overdue conversation with Benjamin about the future of Humana’s support for the theatre’s work was still yet to happen; as I prepared this piece for publication this week, I was told that this meeting would be happening any moment.

In the meantime Actors Theatre, which as of 2020 had a budget around $9.5 million, has hardly been idle: The theatre recently premiered Still Ready, a live, in-person staging of what was originally a virtual docuseries by Christina Acosta Robinson and Ken Robinson; hosted the finals for the Southern Fried Poetry Slam, one of the largest such competitions in the world; has continued to grow both its digital library of animated shorts, music, and community conversations, and its virtual-reality/expanded reality experiments; and maintained its work at the intersection of art and wellness with the Kentucky Nurses Action Coalition, the Clinic, and MindFest. Its fall season is slated to Kate Hamill’s feminist deconstruction of Dracula, Cheryl L. West’s popular Fannie: The Music and Life of Fannie Lou Hamer, and Fleming’s own new adaptation of A Christmas Carol: Ghost Story.

Of course, that looks like only half a season. When I asked Fleming if more would be forthcoming, he reminded me that the spring Humana lineup used to be announced the previous November, and alluded to maintaining “a similar cadence” of programming announcements. Is it possible that we haven’t heard the last of the Humana Festival of New American Plays? While it is unlikely to take precisely the same form as it did of yore, after talking to Fleming, I wouldn’t bet against Actors Theatre remaining a player on both the regional and national theatre scene.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: Over the past few years I’ve talked to a lot of leaders who took over organizations and then faced years of pandemic and protest. That’s not exactly what you signed up for.

ROBER BARRY FLEMING: The details quite were different than what was anticipated. But I think the overall journey is very on target.

Apart from those extraordinary circumstances, can you tell me more about your specific experience? Did you come into a situation where you felt you were set up for success? Were there some issues to solve, or deficits to retire?

The sub-context for most of us is that we were inheriting organizations that had ongoing structural deficits that were going to have to be navigated, and cultural climates that are the reason we have a #MeToo movement as well as a Black Lives Matter movement. These issues are prevalent and ubiquitous in most sectors, and our sector is no less impacted by them, in spite of the narrative of our progressive, enlightened position. We’re still Americans and still human and still fallible in that way.

So yeah, there was a combination of things that I now can discern or understand as challenges about artistic relevance—a feeling that what we were doing did not have its pulse on what was resonant for people, and the general public reifying the sense that our popular form was now an elitist form for a niche audience, generally a niche audience that was predominantly white and affluent. So we’re kind of jesters for the ruling class, and how effective is that, really? And the lack of infrastructure support, both in physical as well as in sustainable practices—while you can sustain some things for a short term, if they are rooted in exploitation, they are doomed to not be sustainable, because that’s not really a natural state for the human animal. Building capacity and ambition alongside artistic innovation is always challenging, and all of that was just kind of amplified. The subscription model failing, the landscape of philanthropy changing priorities—all of those things intersected simultaneously with two public health crises that are endemic: a lack of investment in our physical, psychological health as a nation, and the construction of race and how that’s led to a foundation of genocide, a foundation of misogyny, on the artificial construction of value based on race and gender.

All of those things intersect with a movement that really foundationally has some fictional narratives about what was really happening with the regional theatre movement. Some people remember it as this great moment of bringing the ethos of Europe to America, and saying, “Here’s what culture and art really looks like. We see it on each coast; let’s bring that to the center of the country.” But American culture is deeply informed by genocide and the enslavement project. You don’t find popular culture and American culture not being deeply interwoven with Blackness, even if the form in which that Blackness is doesn’t look like Black or brown people. We have our Adeles, our Jack Harlows; Blackness is all over. And it’s fundamentally American. But our disassociated relationship to that has informed the regional theatre as much as it’s informed any part of our cultural as well as economic system. So it’s this very layered thing.

That’s a very long answer to a question about what were not new problems. But they got amplified in this pandemic environment, where the level of sexism, of the detrimental impacts of the racial construct in North America, have come to a head and continue to have economic as well as cultural impact.

I want to clarify one thing: Many people talked about the end of the Humana Festival as we knew it as being the end of the Actors Theatre of Louisville, but obviously that was just one project of a theatre that programs shows year-round for northern Kentucky and southern Indiana. The Humana Festival was like another season within a season, and it brought a lot of attention and excitement. I do want to ask about your larger plans for the theatre, but first I need to ask about the Humana Festival. At what point did your path diverge from the Humana Foundation? Or is that even how this went down?

My first statement to a local interviewer who wanted to do the story was that there has no new news around this. The Humana Foundation had lost a CEO and were in the process of hiring another CEO. And that party was not in place in the fiscal year that met people’s expectations of when the Humana Festival was supposed to happen; we completed a cycle of support, and a conversation about what support would look like after that agreement had not taken place, because there was no one to have that conversation with in the CEO position. Then, after Tiffany was hired, I was to have a meeting in January, but they couldn’t fit it in the timetable before I went to direct Grace at Ford’s Theatre. And a really ambitious writer decided to write about it anyway, so an article was written cherry-picking things. I have not announced the end of the Humana Festival to this date. I have not had that meeting with Humana yet about the specifics of how they might support us.

So actually, nothing happened—but a lot happened. What I think I observed was that, just like apple pie and hot dogs are American, so is blaming a Black queer for everything that goes wrong or doesn’t work existentially for people, in a culture that is really used to using certain groups as punching bags. People had a lot to say about a lot of things that had nothing to do with Humana and nothing to do with the facts, but they actually needed to work through a lot of stuff. The only thing that has happened is a cycle of support has ended, and there is to be another conversation about what kind of support they might have that would give me an informed position to say, “Here’s how that might evolve into new work.” People’s expectation, that I am an arrogant person who’s just making independent decisions, does that align? Like, if two kings, Jon Jory and David Jones Sr., make a decision to do a Humana festival, do you really think I have enough agency to just say, “Oh, I’ve decided I’m changing this”? That’s not actually aligned with anything that would be recognizable in North American society, as if a Black queer just gets to make whatever decision he wants, independent of discourse. I just found it really fascinating to see how the story escalated, and where it gave people time to really express other displeasures about the changes that are naturally happening in the world, and using this scenario to work through some coastal elitism. It’s like, whatever you’re doing, the only thing that matters is your apprentice program and the Humana Festival.

You know, great creativity and art can happen in many pockets, but there’s the sense that what was valuable about Humana is how it brought Julianne Moore, John Turturro, Kathy Bates, to the fore, not anything rooted in the local community, which is very complex and formed by plantation capitalism. It’s a quintessential North American narrative of disassociation, of exploitation, of a complicated entrepreneurial spirit which created something that captured the imagination and fed stories into an ecosystem that was in desperate need of a clear identity. And what better place to do it than in a place that is diminished by questions like, “Do people wear shoes there?” and “Why do you talk funny?” I mean, I grew up in Frankfort, Ky. I was formed in Kentucky, and Kentucky is as Black and queer as I am, in spite of what Mitch McConnell or anybody like him says. And the deep lack of a sense of humor around the surreal nature of who we are as North Americans in the 21st century—I think it just gets people stuck in a place where it’s like, boy, your discernment and ability to read a story is very limited and reduced. That’s what we’re here to help with. That’s what artists have always been here to help with. Like a court jester, you tell truths that are very uncomfortable for people, you make connections that people generally don’t have the time, energy, or imagination to make.

I don’t think the only things that mattered at Actors Theatre were the Humana Festival and the apprentice program, necessarily, but can you talk about what ATL’s commitment to both new work and to mentorship looks like now?

You know, I think sometimes people talk about growth without really having an end game for that growth. Which reveals much more about inherent human insecurity about value. It’s like, if it’s not bigger and better and larger, then it’s not healthy. One of the things I think I bring as a BIPOC leader is: What’s the quality? Is it useful to have 40 more actors in an oversaturated field? Is that responsible? Is it responsible to do that while they’re exploited within your system, because you have to have certain numbers to work at a certain scale? Are these operating assumptions really serving a sustainable model that leads to good professional development? Or are you demonstrating some of the shadow parts of your society’s insecurities, and need to reevaluate?

We are always looking for partnerships that allow our capacity to match our ambition. It makes no sense to have 40 apprentices when you have 30 employees; how would I possibly responsibly shepherd their experience, and assure that their compensation does not put them in a vulnerable position? This doesn’t make sense to some funders, so for me, that means I guess those aren’t relationships that make sense to continue. We can’t continue an unsustainable model that clearly does not align with our mission, values, and vision. You can’t do a festival where you do not work within those means, and offer work only for the privileged who can afford to go to a graduate school or do an apprenticeship where their economic privilege can augment the lack of compensation. So many things that were rigged in our systems had their own permutation at Actors Theatre; it’s not exclusively here, it’s every regional theatre I’ve ever worked at, to a greater or lesser degree. And it’s in every sector, because it’s a value that is fully vetted by the culture. So my job really is about saying, in what ways do these compromising, unsustainable practices manifest in your current organization? And what can we do to address them in a way that creates safe, equitable spaces, where the #MeToo movement and the Black Lives Matter movement are only relevant in how you are responding to those in responsible and thoughtful and innovative ways?

So rather than 40 apprentices, we just recently became the Society of Directors and Choreographers Foundation Lloyd Richards New Futures Residency theatre. We can do that excellently; that is something we have capacity to do. I think it’s a great place for a BIPOC director or choreographer to hear my own particular way of leading and being engaged in a company that is working through a history of the Breonna Taylor killing, the DOJ being in our backyard to navigate our policing, a place that has had the Humana Festival, a place that is both extraordinarily innovative and extraordinarily challenged by the plantation capitalism narrative. This is a very exciting, dynamic place to have discourse in art and culture.

We’re also continuing to investigate partnerships that are sustainable; we’ve got an extraordinary philanthropist, Christina Lee Brown, who is deeply invested in her Envirome Institute at U of L. They’re extremely invested in comprehensive health, and we know that there’s an intersection between health, storytelling, and the kind of work we’re doing with The Clinic. We also have shows that could win Obie and Tony awards down the line, in that very traditional way, that we’ll be able to announce; the scale of those will be within the the context of the capacity that we have. You can always see how that is being supported: We have a 990 where you can check my salary, you can check everything, so people don’t have to guess that information.

The scale we work at will be the scale that we can fund. We have a couple of projects in development that might not look like a traditional workshop or reading because of the hybrid nature of the work and how it gets developed, how it gets supported. It may look a little bit different, because the model of The Lark and the Humana Festival and Sundance, is not sustainable. That’s not a person’s fault. That’s the reality of the ecosystem that people now get an opportunity to authentically mourn, then innovate and make space for what is next.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org