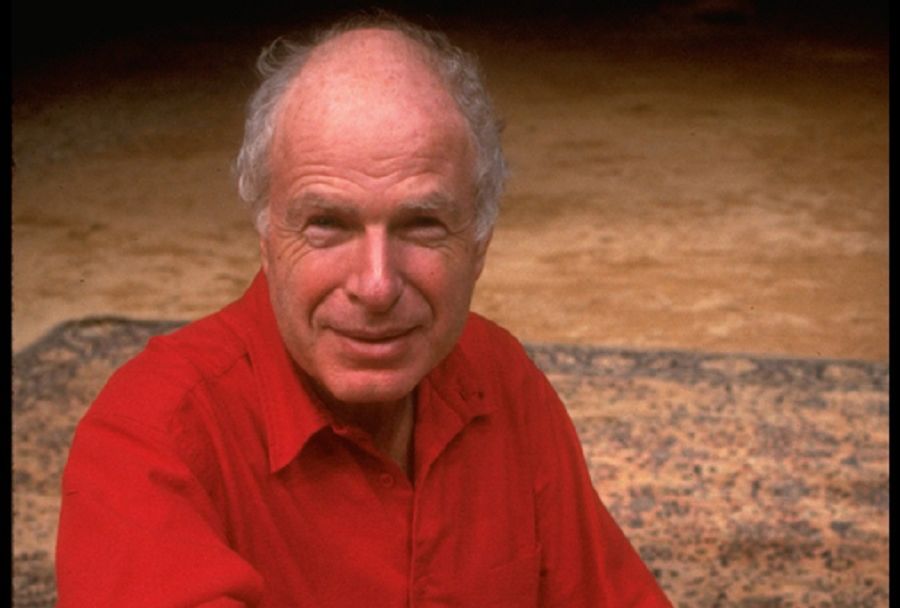

It is impossible to summarize the life and career of Peter Brook. He was 97 years old when he passed away on July 2, and for over 75 of those years he was working at the very height of the profession. His productions of Marat/Sade, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Mahabharata are the stuff of legend. His books The Empty Space, The Open Door, and Between Two Silences are seminal texts for actors and directors.

His influence is everywhere. I began my professional career as an actor, and many of the directors I worked with during that time were heavily influenced by Peter Brook’s work: JoAnne Akalaitas, Robert Woodruff, Anne Bogart, Peter Sellars, Sir Peter Hall. They all had different views on Peter. Some were activated by his writing, others by his productions. Some rejected his experiments. One would refer to him as a “cultural carpetbagger,” another as “the most important director of our time.”

But whether one loved his work and writings (as I did) or were pushing against it, the influence was astounding. His protean output was such that it pushed us all in new directions, whether by honoring his theses or by actively pressing against them. Objectively speaking, it is hard to think of a more crucial and significant voice in the Western theatre in the second half of the 20th century. It doesn’t matter where you go: Whether performing outside with a carpet on the sand or in a producing theatre, whether doing Shakespeare or devised work, whether with seasoned artists at the top of their skills or with non-professional actors, Peter had been there before and had something to say on the matter. And what he had to say mattered deeply to many of us.

There are plenty of books written about the art and the craft of acting and directing. Peter’s writings were crucial to so many of us because they were about far more than craft. They were philosophical texts. They didn’t only teach us what to do; they taught us who to be. They taught us not only how to consider making work, but how to consider why we make work at all. When I directed Henry V with maximum-security inmates at a men’s facility in the corner of the Mojave desert (the first full-length play I ever directed), I thought of Peter’s work continually. We had next to nothing to make the play with in that prison chapel, and I found such comfort and clarity in Peter’s belief that in the end, a person can enter an empty space, someone is there to watch, and a theatre is formed.

There was something of the mystic about Peter Brook. He was a seeker in every way. He was immensely curious. Having examined one idea fully, he’d shift to another, easily setting down what came before and unapologetically moving to new ground. He helped remind us that the vagaries of the profession shouldn’t push us away from what is finally sacred about the work that we do.

In The Open Door, he writes: “’Holy Theatre’ implies that there is something else in existence, below, around, and above, another zone even more invisible, even farther from the forms which we are capable of reading or recording, which contain extremely powerful sources of energy.” Every director and actor I know understands this on some level. Peter’s brilliance as a writer and lecturer was twofold: He could help us consider things that we never thought of, and just as usefully could put into words things that are deeply understood but unarticulated. One could say, reading Brook, Wow, I never thought of that, or, Aha, there it is—I’ve always known that, and by Peter giving voice, it refined and validated our deepest thoughts and instincts.

While Peter could make work of epic scale, and was a showman of the first order, it was in his later work where the distillation of his genius most powerfully manifested. By the end, what to leave out, for Peter, was clearly as important as what to include.

So it was the honor of a lifetime to have him bring his spare and gorgeous production of Battlefield to us at the Guthrie in 2017. Over dinner with his colleague Marie-Hélène Estienne and the director Dominique Serrand, Peter told the most astounding stories of his journey and learnings, none of them about the theatre, all of them about the human experience, and the curious sensation I had was both that he had told these stories before to others, and also that they were for our ears only. On the opening night of Battlefield, we were in the Kitchak Lounge, which looks out at the cantilever that juts from the building, allowing sweeping views of the Mississippi River. He held my hand as I shared with him that it is called the Endless Bridge. He paused, leaned toward me, and said quietly in my ear, “The Endless Bridge. That would be a great title for your book.” If I ever do write a book, I may indeed use that title, but it could just as easily be the name of Peter Brook’s biography. He searched endlessly to create bridges: between cultures, between classical work and our contemporary age, across the great distances that stretch between people, and not least of all, between and among artists themselves.

My goodness, what a thinker, what an artist, what a human. How lucky we are that he lived and worked in our time. The empty space that Peter wrote about is now, upon his passing, an empty space in many of us. We will wait (patiently, as it will certainly require) for another like him to walk in and inhabit that space, seeking to engage, delight, provoke, connect, and love us in the astounding way that Peter Brook did.

Joseph Haj is the artistic director of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis.