On a cloudy Wednesday morning, less than a week before he was to make his overdue, pandemic-postponed Broadway debut, musical theatre writer Michael R. Jackson was scrambling. His idiosyncratic, existential, metafictional musical A Strange Loop was days away from opening, after the creative team had been forced to cancel a first preview performance when COVID-19 cases were discovered within the company. That meant less time for Jackson to finesse scenes and songs, causing a burst of small panic behind the scenes. Originally scheduled to start previews on April 6, the production launched instead on April 12, just in time for the show’s understudies to spring into action and for Jackson to make revisions. It opened just two weeks later, on April 26, becoming a bona fide critical smash, with Jackson being celebrated for the musical’s craftsmanship, fearlessness, and unbridled humanity. Sales have been strong, and last night’s Tony wins—for Jackson as the show’s book writer, and A Strange Loop as best musical—are sure to bolster the show’s fortunes.

That Wednesday before opening, Jackson was thinking back to the beginning of rehearsals.

“It was a really exciting and emotional day,” Jackson, 41, recalled from the Washington Heights apartment he’s lived in for 15 years. “I told the room that day that it was really amazing that this thing I wrote alone in a room up the stairs of this little old lady in a bungalow house in the middle of nowhere in Jamaica, Queens—that I wrote this monologue as a little life raft for myself on my little Compaq Presario laptop—somehow, over the years, blossomed into this mighty ship that landed on Broadway.”

The seeds for that ending were planted, he thinks, when he added the lyric to the opening number calling what we were about see a “Big, Black, and queer-ass American Broadway show.” He confessed, “Even when I wrote that, I didn’t think the show was going to Broadway, and that wasn’t even what I was trying to do. I was trying to make what felt like a Broadway show to me—my version of what that was supposed to be. So it’s just wild, all that manifesting and that sort of artistic rigor ended up resulting in the show going to Broadway. It feels like a miracle or magical, or something otherworldly, that that could happen.”

A Strange Loop follows Usher (played Jaquel Spivey in his first professional gig out of college), a 25-going-on-26-year-old “overweight-to-obese” Black queer musical theatre writer making a musical about a 25-going-on-26-year-old “overweight-to-obese” Black queer musical theatre writer, ad infinitum. The character’s name is both a reference to the blockbuster-selling R&B singer-songwriter and to the day job the character holds at The Lion King on Broadway, counting down intermissions while assisting entitled wealthy patrons to their seats and dreaming up his breakthrough show; we spend the majority of the show in his mind. Accompanying Usher is a Greek chorus of six “Thoughts,” played to perfection by the spectacular sextet of L Morgan Lee, James Jackson Jr., John-Michael Lyles, John-Andrew Morrison, Jason Veasey, and Antwayn Hopper, each of them contrasting, conspiring against, or calling him out at every turn.

The origins of Jackson’s crowning achievement have become somewhat mythic: Shortly after graduating from New York University’s Dramatic Writing Program in 2002, a 21-year-old Jackson wrote a thinly veiled monologue, a coping mechanism for his career anxiety as a fresh-out-of-college playwright called “Why I Can’t Get Work,” that became the kernel for the show. That monologue was about a young Black gay man walking around New York assessing his life, his career trajectory, and his worth as a Black gay man who is “too fat,” “too femme,” and “too Black” for the culture.

Two years later, while Jackson was attending NYU’s Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program, a peer of his, Darius Marcel Smith, performed an original song about a one-night stand with another man, and the guilt and shame that came along with being a God-fearing Christian. Inspired, Jackson jotted a lyric in his notebook: “All those Black gay boys I knew who chose to go on back to the Lord.” This phrase, and a musical motif from Tori Amos’s “Pretty Good Year” (the third single from her sophomore effort Under the Pink) inspires him to pen “Memory Song,” snapshots from his coming of age in Detroit as a gay boy with a religious and homophobic upbringing; it would be the first song he’d write as composer and lyricist, and the first germ of what would one day be A Strange Loop. The monologue soon grew into a solo show titled Fast Food Town, performed to mixed reviews Off-Broadway at Ars Nova.

Originally titled “Gayville”—a riff on Exile in Guyville, Liz Phair’s seminal 1993 bedroom-pop indie-rock debut, itself a response to the 1972 Rolling Stones’ cock-rock album Exile on Main Street—Jackson’s musical followed an ultra-self-aware, disillusioned, and furious 20-something undergoing a quarter-life crisis and the downward spirals that come with wading through a liminal space of being a postgraduate, pre-career artist trying to find their corner of the sky. While Phair’s influence looms over the project (check out “Inner White Girl”), her inclusion was a bit more deliberate at first.

“There was an old, old, old draft of A Strange Loop wherein Usher, the character in the musical, was writing these mashups of his songs to Liz Phair songs, mostly to her Exile in Guyville album, and there was a narrative also within the piece where he was trying to reach out to her and get her permission to use her music in the show but also talking to her through his own music mashed up with hers,” Jackson explained. “In real life, I was trying to track her down and get the rights to use her music as well.”

Eventually Phair got back to Jackson, encouraging him to write his own material and make it personal. So he scrapped the mash-ups and began to purge, but thankfully he didn’t take himself too seriously. As a result, A Strange Loop is a disruption, an existential treatise on the soul as it wrestles with topics and taboos at the crossroads of the sacred and profane, all while eviscerating the musical theatre form. Yet its most alluring takeaways come from Jackson’s obsession with the self and with self-identity—an impulse that no doubt be traced to the singer-songwriters he adored growing up.

“There was a song I had written in the show that’s no longer in it called ‘Fan Boy’ that was a mashup against the Liz Phair song called ‘Strange Loop,’ and for years I never knew what the term ‘strange loop’ was—it was just a song on the album that I just really liked,” he clarified. One day it dawned on Jackson to type the phrase into Google, which led him to Douglas R. Hofstadter, the scholar of cognitive science and comparative literature. In his Pulitzer-winning 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Hofstadter coined the term “a strange loop” to describe the navel-gazing nature of individualism and intelligence, writing: “In the end, we are self-perceiving, self-inventing, locked-in mirages that are little miracles of self-reference.” The term, used to describe the paradox of one’s sense of self, is also mirrored in Jackson’s allusions to what W. E. B. DuBois called the “double-consciousness” of African American selfhood created by racism and anti-Blackness. Thus began a series of strange loops, with Liz Phair leading Jackson to Hofstadter, which in turn led him to the title and structure of his groundbreaking hit.

A Strange Loop is hardly the first metafictional musical. There was Jonathan Larson’s semi-autobiographical rock monologue-turned-musical, tick, tick . . . BOOM!, adapted by Lin-Manuel Miranda into a feature film last year. There’s also Jeff Bowen and Hunter Bell’s [title of show], a one-act musical about four characters creating the musical they’re simultaneously performing, which played at the Lyceum Theatre 14 years prior. Yet Jackson’s acclaimed pop-rock Bildungsroman actually follows a lineage of sui generis metafictional musical theatre writers of the post-Black Arts Movement tradition. Like Kirsten Childs’s The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin and Stew’s Passing Strange before it, A Strange Loop is a funny, life-affirming coming-of-age story about a young, gifted, and Black creative as they journey toward self-discovery and self-acceptance. Fusing gospel, jazz, punk, and blues with rock music, Passing Strange is a fourth wall-breaking picaresque odyssey of Black identity and code-switching against a backdrop of Berlin’s 1987 May Day riots. Through a mélange of ‘60s girl group pop, R&B, and showtunes, The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin explores a young woman’s battle with internalized racism and self-worth while surrounded by racial profiling, de facto segregation, and sexism in the wake of 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

A Strange Loop continues the conversations that began with those genre-defying musicals, merging gospel, folk rock, bedroom pop, and alternative music while forging a new path for Black and queer storytelling in the age of Truvada. In American theatre, white gay men have co-opted and oversaturated the marketplace for LGBTQ narratives. Whether it’s the gay Civil Rights movement (Mart Crowley’s The Boys In The Band, Dustin Lance Black’s 8), or the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes, Steven Dietz’s Lonely Planet, William Finn’s Falsettos), or collective trauma (Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife, Moisés Kaufman’s The Laramie Project, Martin Sherman’s Bent, Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy, and Douglas Carter Beane’s The Nance), or even queer joy (Fierstein’s La Cage aux Folles, Sherman’s The Boy From Oz). Naturally, a show centering a plus-sized, dark-skinned Black queer man with ambition stands in opposition by design. But A Strange Loop goes further than that, showing no qualms about interrogating such issues as the HIV stigmatization of the Black queer community, racial fetishization, internalized homophobia, parental blackmail, self-loathing, and the paradox, trauma, joy and vicissitudes of being Black and queer and religious.

Indeed, in its brisk 90 minutes, A Strangle Loop both deconstructs and glorifies Black art and queer iconography with absolute abandon. Bristling with references to The Golden Girls and Designing Women, advice columnist Dan Savage, and spoken word artist Audre Lorde, Stephen Sondheim and bell hooks, Scott Rudin and Betty Friedan, the show skews the lines between gay and straight, Black and white, high and low culture with aplomb, putting the musical-within-a-musical in a league of its own, while bridging divides very few of the aforementioned shows have.

No one is safe from critique. One of the biggest targets of Jackson’s ire is Tyler Perry, the multimillionaire movie media mogul, well known for his lowbrow, Chitlin’ Circuit-inspired entertainment, full of ham-fisted messages about the power of prayer. Hallmarks of Perry’s works are satirized and spoofed with surgical precision in A Strange Loop: The stalwart matriarch, the low-income black sheep with an addiction to crack cocaine, the “Strong Black Woman” meandering through life as a lonely spinster with an offstage Ken doll lover interest. Jackson’s contentious relationship with Perry began when a childhood friend introduced him to the impresario’s work shortly after he arrived in New York in 1999; as a gag gift for her birthday, he purchased tickets to see a staged production of Why Did I Get Married? at the Beacon Theatre, starring R&B vocalist Kelly Price, who wore a fat suit in the first act. In A Strange Loop, Usher calls Perry out for his “simple-minded hack buffoonery,” but the mockery is tinged with anxiety; we get the sense that Usher might genuinely be afraid he will create such color-by-number material himself. With each gibe, Jackson holds up a mirror to both the protagonist and himself with profound hilarity and heartbreak.

In one of the show’s most subversive, farcical numbers, “Tyler Perry Writes Real Life,” Usher is confronted by his Thoughts as they masquerade as historical Black figures: Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Marcus Garvey, Harriet Tubman, and a proxy for every Oscar-bait antebellum picture simply given the name Twelve Years a Slave. Throughout the tune, the Thoughts chastise him for imagining that he is above Perry’s work, especially when an agent offers him an opportunity to quickly ghostwrite a gospel play—news that overjoys his devout parents but repulses Usher. While Usher’s critiques about Perry’s oeuvre have been echoed by his peers, it is his pointed criticism of the filmmaker’s stigmatization of Black queer sexuality and HIV that come into sharpest focus, especially where Perry’s “hate the sin, not the sinner” ethos is concerned. Toward the end of the show, Usher leads his Thoughts in a revival number titled “AIDS Is God’s Punishment,” ridiculing Perry’s proclivity to perpetuate stigma and condone the belief that people living with HIV are sinners who deserve punishment for loving and living out loud. It is a primal scream, Usher’s direct confrontation with the fear mongering and homophobic scripture preached down to him as a youth, as well as a moment of grief for a friend he lost to AIDS. Jackson doesn’t just critique Perry and the Black church here; he also zeroes in on the American theatre and its role in disregarding Black queer people and their stories in favor of white comfort.

“Being willing to challenge any assumptions or popular points of view, being able to question any orthodoxy or status quo—to me that goes in all directions,” Jackson said. “That means if Black Twitter is into something and I’m not into it, that means being willing to risk the ire of Black Twitter, that means being willing to risk the ire of the theatre world, that means being willing to risk the ire of liberal Democrats, of conservatives, of whomever—white people, Black people, everyone, treating everybody the same—and being willing to stand alone, if necessary, in your truth.”

A lot has changed for this musical theatre provocateur in recent years. A major career shift came when A Strange Loop was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2020, becoming only the 10th musical to earn the honor overall and the first to win the award without a Broadway run. Jackson, who was watching an episode of Bravo’s The Real Housewives of Atlanta while conversing with playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins when he received the news, not only made history as the first Black artist to win for writing a musical; he has also become part of a string of Black-authored Pulitzer winner, with Jackie Sibblies Drury’s divisive critical race experiment Fairview nabbing the award in 2019, and Katori Hall’s The Hot Wing King taking the award in 2021 and James Ijames’s Fat Ham winning it this year.

That win was part of the momentum building behind A Strange Loop, which had its Off-Broadway premiere at Playwrights Horizons in 2019, then a limited engagement at Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company last year. Joining a team led by producer Barbara Whitman and Page 73 Productions, the show’s current Broadway outing has attached an impressive Rolodex of stars to its co-producers’ roster, including RuPaul Charles, Don Cheadle, Jennifer Hudson, Mindy Kaling, Billy Porter, Ilana Glazer, Alan Cumming, Zach Stafford, Cody Renard Richard, Benj Pasek, and Justin Paul. It garnered a record 11 Tony nominations, and though it only took home two of those, they were ones that count: Best Book of Musical and Best Musical. (Best Original Score went to Six.) These wins cap a busy awards season that saw it take home Outstanding Production of a Musical at the 2022 Drama League Awards, and an Outstanding Actor in Musical Award for lead actor Jacques Spivey, who also got an Outer Critics Circle Award and a Theatre World Award honor. Meanwhile L Morgan Lee’s performance earned her the distinction of being the first openly transgender performer to originate a role in a Pulitzer-winning piece of theatre and the first to receive a Tony nomination. Jackson was also included in Time Magazine’s Time 100, an annual listicle of the most influential people in the world, where he was nominated by Porter.

Like many writers for the theatre, he has also become an in-demand writer for TV and film. He recently joined the creative team of the Amazon original series I’m a Virgo, a half-hour superhero satire from writer-director-producer Boots Riley (Sorry to Bother You), starring Jharrel Jerome. Jackson is also developing a TV series for ABC Signature and sold an original pitch to write an untitled horror feature for A24, which Ari Aster and Lars Knudsen are producing under their Square Peg banner. But not to worry, theatre fans, Jackson is still at work on various stage works: White Girl in Danger is a new pop-rock musical partly inspired by classic daytime soaps and ’90s-era Lifetime movies, in development with the Vineyard Theatre Off-Broadway and director Lileana Blain-Cruz; and Teeth, based on the 2007 indie vagina dentata horror comedy by Mitchell Lichtenstein, is being workshopped in collaboration with composer-lyricist Anna K. Jacobs. Jackson has also been commissioned by LCT3, Lincoln Center Theater’s program for emerging artists, to pen Accounts Payable, an original musical inspired by the days when he was slumming it as a finance clerk and executive assistant.

From those bleak early to his current success, Jackson’s North Star has been his dedication to his craft and to the truth.

“I do feel like I’ve changed in a lot of ways,” Jackson said of the past few years in the spotlight. “But I also feel like I am the same person I’ve always been, which is to say I’ve always been somebody who has been trying to get at the truth of life as I understand it and constantly try to scavenge and dig deeper and get past the surface level answers of questions I might be having or that confuse me. I feel like as a young person, a young writer, I was doing that from a much younger perspective.

“That has been the trail I tried to blaze: to be willing to have an unpopular opinion and have a nuanced opinion,” he continued. “That’s only gotten more important to me, especially over these last couple of years, as lots of cultural conversations have taken hold and really gotten louder. I have lot of criticisms and questions in places where I stand apart from my peers, and I have to be willing to stand in that place. I try to stand in that place respectfully and with compassion, even when I want to read people for fucking filth. Even when I have utter contempt for some people and ideas that I see being bandied around.”

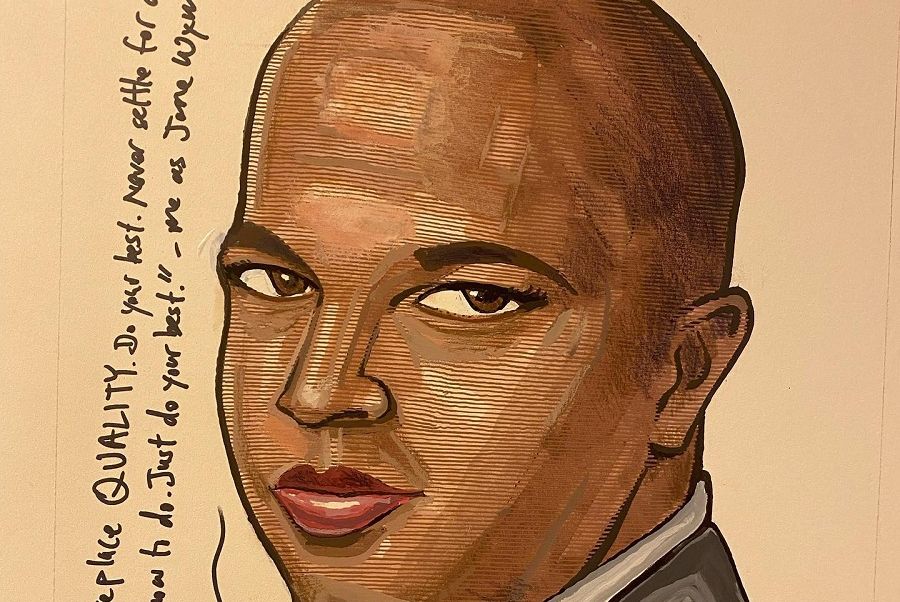

As uncompromising as his show’s protagonist, Jackson stood in his truth, and, upon receiving his Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical to a standing ovation, encouraged the American theatre to opt for quality in art. This is a fulcrum moment not just for Jackson, but for every outcast and outlier building their life rafts on the island of misfit toys that is the theatre at its best. As a patron sings to Usher in “A Sympathetic Ear”: “If you’re not scared to write the truth, then it’s probably not worth writing / And if you’re not scared of living the truth, then it’s probably not worth living.”

Marcus Scott is a New York-based playwright, musical writer and journalist. He’s written for Architectural Digest, Time Out New York, The Brooklyn Rail, Elle, Essence, Out and Playbill, among other publications.