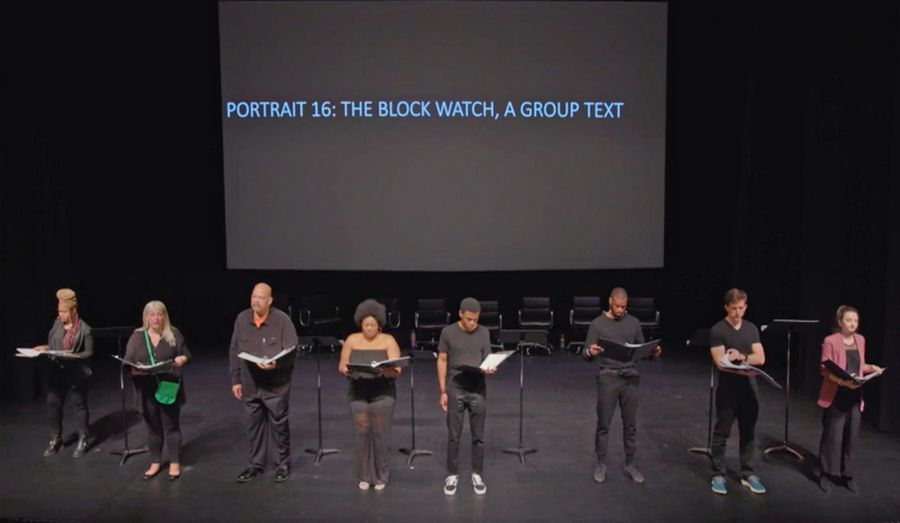

TyLie Shider’s Whittier is a contemporary docudrama following a diverse community of neighbors quarantined in Whittier, Minn., days after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. The play is inspired by the graffiti, lawn signs, and murals created in protest of Floyd’s murder. It is adapted from focus groups, interviews, and talks Shider conducted with neighbors, small business owners, and community leaders of faith during the 2020 uprisings in his neighborhood.

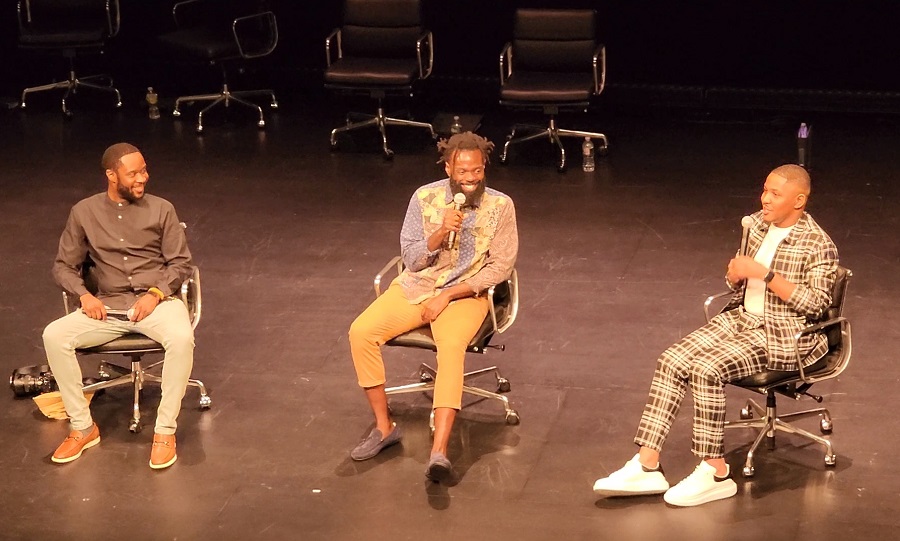

Shider is the inaugural playwright in residence at ArtYard in Frenchtown, N.J., which presented a staged reading of Whittier on Sat., May 21, 2022, at its 162-seat McDonnell Theater. The Whittier reading was directed by Andrew Binger and produced by Deonté Griffin-Quick, ArtYard’s guest theatre curator. These three Black, New Jersey-bred theatremakers sat down for a conversation to discuss the show’s gestation and their work in the theatre. As a 2022-23 McKnight Fellow at the Playwrights’ Center, Shider will return in the fall to workshop Whittier in the city of the show’s inspiration.

TyLie Shider: I want to take this opportunity to shed some light on theatremakers from New Jersey. I think because of our coveted proximity to New York, it is easy for us to get swallowed up by the hubbub and lights of the larger city. The first person who comes to mind when I think about New Jersey-bred theatremakers is Amiri Baraka and the mission-oriented plays he contributed to the Black Arts Movement in the ‘60s.

Andrew Binger: This is an outstanding opportunity to shine a light on Black theatremakers and to tell a Black story by a Black storyteller. And we’re taking up space intentionally to showcase this work. Best of all, we get to do this in our home state and continue to enrich the New Jersey arts and theatre communities. Wherever Whittier goes, we’ll be able to say a part of the play’s journey happened in New Jersey. I hope more and more great work will find its way or its start in Jersey, and professional artists from Jersey (and beyond) will see the state as a destination.

Deonté Griffin-Quick: I love this idea of “taking up space intentionally.” This collaboration among Black men is so special to me, because we don’t see enough of it, especially in New Jersey. We’re often overlooked by the New York and Philadelphia markets. So I think we’re adding to the legacy of Black New Jersey theatremakers. I also want to celebrate folks like Ricardo Khan, Marshall Jones III, and Rodney Gilbert, who have created great work here too.

Shider: I was born and raised in Plainfield. It was a predominantly white Republican suburb when my maternal grandparents moved there from the South in the ’60s and ran into the race riots in ’67, which led to a “white flight” and the ensuing decline of jobs and businesses. Thus I inherited a very different city than my parents, and I wouldn’t necessarily call it a theatre town—although it is the home of funk! My uncle, Garry Shider, left home at 16 and formed a funk band, and eventually joined Parliament. What part of Jersey are you all from? Would you call where you’re from a theatre town?

Griffin-Quick: I grew up in Linden, and it was not—and still isn’t—a theatre town by any means. Growing up, some of my earliest memories of theatre were at Newark Symphony Hall and going across the bridge to Broadway. I think we can all agree that for a long time we were not aware of all of the professional theatre here in New Jersey.

Binger: I was born in the City of Newark and grew up in the greater Newark area: Orange, East Orange, etc. I also remember Newark Symphony Hall, but didn’t understand the New Jersey theatre scene until much later. I remember my first New York theatre experience seeing The Lion King on Broadway.

Shider: How did you get started in the theatre?

Griffin-Quick: My grandmother wrote plays for our community choir when I was a child. So I always attribute that to the genesis of my desire to be an actor. Then I went to the Academy for Performing Arts in Scotch Plains, where I trained and eventually branched off to do local theatre shows.

Binger: In elementary school, we had a few activities that I didn’t realize were theatre experiences—skits and whatnot. It wasn’t until middle school where I could actually take a theatre class.

Shider: Deonté, you and I met through the Kennedy Center’s Arts Across America.

Griffin-Quick: Yes, the Kennedy Center reached out to me and the New Jersey Theatre Alliance team to participate in the Arts Across America program, a digital platform launched at the beginning of the pandemic to showcase artists and organizations telling the stories of their communities. As the curator of that showcase, I put out a call for artists working with some of our member theatres, and your name came up because you were working with the Theater Project at the time.

Shider: Yes, Mark Spina and the Theater Project have been very integral in the professional development of my plays. Andrew, we workshopped one of my cerebral plays after meeting at 48 Hours in Harlem, am I remembering correctly?

Binger: That’s right, TyLie, we met at 48 Hours in Harlem in 2018. Being from Jersey, I was excited to hear someone else was also from Jersey and figured it would be valuable to stay connected. And we workshopped Manual Weapons of Fire shortly afterwards.

Shider: Right! I’m excited to work with you all on Whittier. This play has been gestating in my mind for a while now, and I am anxious to share it with a live audience and learn more about it. How important is a live audience to new-play development?

Binger: Live audiences are critical to new-play development. It’s like having a personalized focus group. Now that we’re back to in-person programming, you’ll get the opportunity to see how the audience reacts and hear their feedback in real time. They’ll ask questions and offer up feedback that’ll help guide future revisions of this piece.

Shider: That sort of civic engagement inspired the play. I think theatre is incomplete without a live audience.

Griffin-Quick: I think having a live audience makes a huge difference when developing a new play. We have to know how audiences connect and respond to a play in its early stages so that the playwright can further process and refine the work. We’ve seen a lot of virtual programming over the past two years, and it’s fine. But there’s nothing like getting artists and audiences in the same room feeding off of each other’s energy.

Shider: Although Whittier is set against the backdrop of the 2020 uprisings in Minneapolis, I wanted to zoom in on the way in which a diverse community of neighbors came together to protect their neighborhood in the wake of a recent tragedy. Therefore, the play is less about the inciting incident and more about the ensuing series of events it caused. At the time, I was writing about the Plainfield riots in 1967, which corresponds with the Newark Rebellion, and I was gripped by the similarities between the past and the present: police brutality, uprisings, the threat of outside agitators, etc.

Griffin-Quick: It’s so interesting that stories of different times and different communities can still be so connected. And I think we have a responsibility to keep telling these stories. That’s why I’m so excited that we brought this play reading to the East Coast, because it feels like the conversation has been silenced. We aren’t talking about these issues the same way we were in 2020. But they’re still relevant.

Binger: I really think the last two years will probably serve as a jumping-off point for so many rich stories. In 2020 so many people saw the challenges Black individuals live for the first time. Artists are always doing great work capturing and amplifying these moments. This play can help reignite some of the fervor and energy we need to continue having these conversations. We can’t let that rebellious energy die.

Shider: The Black Arts Movement took up residence in alternative spaces. ArtYard feels like a new and alternative space for theatremakers. I think this collaboration is the beginning of something great.

Griffin-Quick: I agree. I’m grateful that we are all working on this project together, because there is something unique about it. Three Black artists coming together to produce theatre in a space that was designed to center the needs of artists is really something remarkable. I think the model that ArtYard is incubating could have a great impact on the field as we look at more equitable ways to support artists and the communities we serve.

Binger: Over the last few years I’ve been very interested in the idea of space. We need art in traditional spaces as well as non-traditional spaces. How can we bring people into our space and go where the people are? How can we transcend boundaries in our work? This made the work of our predecessors quite powerful.

Shider: I want audience members to walk away with a new “friend in their head” from the play. Perhaps there is a character in the play they could relate to. What do you all want audiences to take away from the staged reading?

Griffin-Quick: I hope the audience leaves understanding the true meaning of community. As you said, this story is ignited by a tragic incident, but the focus is more so on the shared experience that came afterward. As a society, how can we support and hold space for one another? Because we are more alike than different.

Binger: After seeing this piece, I hope people are encouraged to continue fighting for justice in whatever way they are able to. We all have different strengths and bring different things to the table. How can we work collectively to ensure we tell these stories, but also so that we change the realities that inspire these stories?

Shider: Yes, a call to action.

TyLie Shider is a Minneapolis-based writer and a 2022-23 McKnight Fellow in Playwriting at the Playwrights’ Center (PWC).

Deonté Griffin-Quick is a nationally recognized, award-winning arts administrator, actor, and consultant who serves as director of programs and services at New Jersey Theatre Alliance.

Andrew Binger is an educator, actor, director, consultant and arts administrator from Newark, N.J., where he is the producing artistic director of Yendor Theatre Company (YTC).