In her new book Pinter and Stoppard: A Director’s View (Methuen Drama), Carey Perloff explores her collaborations and discoveries in the rehearsal room alongside two great English playwrights, with an eye to what future interpreters can learn about these writers and their work. In this excerpt, which has been condensed and edited for this context, she hones in one of Pinter and Stoppard’s less noted commonalities.

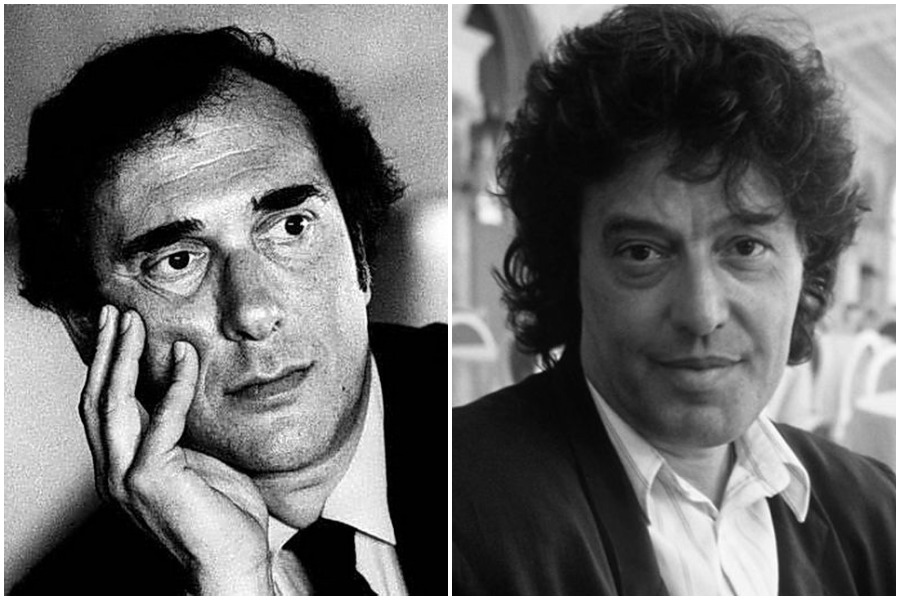

If finding a playwright’s “voice” is a key to realizing their work onstage, a crucial aspect of both Pinter’s and Stoppard’s life histories is that both are Jewish. Not only Jewish, but Central European Jews who came of age in the traumatic period of the Second World War and the Holocaust. This salient fact has begun to be more deeply explored in recent years; for me, the “Jewish thread” has consistently informed my own understanding about, and interpretation of, their work. In the New York theatre, where Judaism is pervasive, the fact that these two major figures happened to be Jewish may seem inconsequential. But in the universe of post-war Britain which Pinter and Stoppard entered as young men and young writers, it was significant. I would like to argue that Pinter’s and Stoppard’s Jewish heritage ultimately had a profound impact upon their plays and is a useful angle to explore in the rehearsal room.

One could argue that Pinter always wrote from a place of opposition, that he needed an enemy to energize his activity in the world. In an interview with Laurence Bensky in 1966, Pinter commented,

Everyone encounters violence in some way or other. It so happens I did encounter it in quite an extreme form after the war, in the East End, when the Fascists were coming back to life in England. I got into fights down there. If you looked remotely like a Jew you might be in trouble. Also I went to a Jewish club, by an old railway arch, there were quite a lot of people often waiting with broken milk bottles in a particular alley we used to walk through.

Of course, the flip side of violence was a kind of sexual charge that Pinter talked a great deal about when remembering his wartime life in London. Many years later, I wrote to him about a speech in Old Times in which Anna, trying to persuade Kate not to go out walking in the park that evening, says, “The park is dirty at night, all sorts of horrible people, men hiding behind trees and women with terrible voices, they scream at you as you go past”; I wondered at the tone of the speech, the graphic violence in it, and asked Pinter for his thoughts. He wrote back immediately, “I don’t understand why you don’t understand the speech ‘The park is dirty at night’. It seems simple enough to me. The park embodies a menacing, alien world, violent, sinister, dangerous, as opposed to the comfort, peace and security of their room. The speech actually refers to the atmosphere of Hyde Park in the ’50s and ’60s quite accurately.” But he went on to say, “The park was full of prostitutes then, men behind trees etc. It was a very ugly and—to some, very exciting place. Our conversation definitely revealed something else, which is that Anna is expressing her own revulsion and fear in the speech.” The fraught atmosphere of his youth became the visceral reality of his characters, for whom the outside world is almost always a place of threat and potential danger.

Being alert to attack was part of Pinter’s DNA. When he came to write The Birthday Party, Pinter explained that the impetus for the play was an image of a man sitting alone in a room, startled by a knock at the door. “The idea of the knock came from my knowledge of the Gestapo,” Pinter told Mel Gussow in 1988. This aggression was not an abstract or metaphoric notion to Pinter; it grew out of his lived experience. As critic Francesca Coppa points out, “The plotline of The Birthday Party was being played out as the most utter realism throughout Europe during Pinter’s childhood and teens.” Thus, when Barry Davis of The Jewish Quarterly asked Pinter in 1992, “In the final analysis, you feel a Jew when you feel beleaguered?” Pinter replied that he identified “with Jewish suffering…particularly in relation to the Holocaust. I find that the poetry, the art that has come out of the Holocaust, is very strong and leaves a very strong impression.”

An obsession with the use and misuse of language, and the delight in the sound and structure of words, is central to Pinter’s work. A desperate desire for clarity is coupled with the impossibility of ever achieving a true connection between thought and speech. “I don’t think she’s got it clear,” Max frets in The Homecoming. While the Jewish American linguistic tradition belonging to novelists like Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud was quite different from Pinter’s own creative impulses, and while he never characterized himself as an “Anglo-Jewish writer”, there is no doubt that his passionate love of language and his ability to mine emotion with the precise and often surprising word is closely connected to the language he heard and studied during his Jewish upbringing. To speak in Pinter is rarely to confess or to reveal; it is to bear witness, to remember, to hide, to protect, to play games, to interrogate, to debunk, to learn, to query, to attack, to destabilize.

Perhaps this is why so many exchanges in Pinter’s dialogue are non sequiturs—speech acts do not follow each other in a predictable way. It is certainly why Pinter’s texts are so hard for actors to memorize. Pinter’s acute focus on the shape and possibilities of the English language was connected to his opposition to cliché, cant, and political obfuscation. Years later, in the wake of fascism and the horrors of war, the poet Spooner would lament to his host Hirst in No Man’s Land: “All we have left is the English language. Can it be salvaged? That is the question.” The implication is that the right words can save us from barbarity. As well as making us laugh.

As to Stoppard, nee Sträussler, I have always wondered whether the feeling of emptiness and “not knowing” that resulted from his traumatic childhood was in the back of his mind when, in his first major play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, his character Guildenstern watches the Player trying to “enact death” and emphatically corrects him: “No, no, no…you’ve got it all wrong…you can’t act death. The fact of it is nothing to do with seeing it happen—it’s not gasps of blood and falling about—that isn’t what makes it death. It’s just a man failing to reappear, that’s all—now you see him, now you don’t, that’s the only thing that’s real: here one minute and gone the next and never coming back…” The mysterious disappearance of his father, and by extension of his whole personal history, would prove to be a crucial theme for Stoppard throughout his playwriting career.

So was the notion of luck. After all, it was in some ways an act of luck that the Sträussler family landed in England after the death of Eugen, just as in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, it is luck that determines whether the coin lands on “heads” or “tails,” and a lucky accident in Travesties that maroons a group of famous artists safely in Zurich during the war.

After age 5, there was nothing left of his father in Stoppard’s life. With his mother Marta and his brother Peter, the Strausslers remained in India for the duration of the war; Marta worked for the Darjeeling outlet of the Bata shoe corporation. It must have been a desperate time for her, though Stoppard’s own memories of India are happy ones. In 1945 Marta met and married Major Kenneth Stoppard, returning with him to England after the war with her sons, who took her new husband’s surname. That seems to have been a given, but in her biography of Stoppard, Hermione Lee reports that in the journal he kept for his son Ed in 1975, Stoppard wrote that he regretted losing his original surname, and wished that he had learned more about his family history: “Mummy has a curious reluctance to talk about the past. I intend to persuade her to do so.”

In his most recent (and most Jewish) play Leopoldstadt, Stoppard puts this sense of disconnection into the mouth and hands of the matriarch Emilia, a woman who spends the first act of the play holding a family photo album. As she looks at the small black-and-white snapshots, she remarks sadly, “You don’t realize how fast they’re disappearing from being remembered…Here’s a couple waving goodbye from the train, but who are they? No idea! That’s why they’re waving goodbye. It’s like a second death, to lose your name in a family album.” By the time he wrote the heartbreaking ending of Leopoldstadt, Stoppard was in the midst of a long journey of self-discovery, part of which involved a meeting in 1999 in Prague with the widow and two daughters of his father’s boss at the Bata hospital.

He related the story in an essay written for Talk Magazine entitled “On Turning Out to Be Jewish.” It seems that one of the women he met, Zaria, showed him a scar on her hand, which she had received from having walked through a glass door as a child; she told Stoppard that it was his father (everyone’s favorite doctor at the hospital) who had stitched her wound. Stoppard writes that, as he touched her scar, he realized it was the only thing of his father’s he had encountered since leaving Zlin as a child. This was a wrenching Proustian moment for a person who had barely evinced sorrow upon learning of his father’s death the first time round. “In that moment, I am surprised by grief, a small catching up of all the grief I owe,” he wrote about the incident.

This prevailing sense of loss (and survivor’s guilt) underlies much of his work; Stoppard seems both preoccupied by and reconciled to the despair that comes with a culture being lost over time, as his past (and the language and world view attached to it) was to him. Imagine it: In May 1933, four years before Stoppard was born, 50,000 books by Jews and other “traitors” were burned in Berlin, in a fanatic attempt to eradicate Jewish culture. Stoppard, full of a Central European love of culture, is obsessed with lost artifacts and with the fragments of ancient writing that have survived. There is a crucial scene in Arcadia in which a young pupil, Thomasina, despairs about the disappearance of so much Greek literature: “How can we sleep for grief?” she exclaims. To which her tutor Septimus replies, “By counting our stock…We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those left behind.”

I remember the day we staged that scene when I rehearsed Arcadia in 1994, and again in 2014. It is a scene filled with despair in spite of its comic overtones, and as we worked, it was hard not to hear, in Thomasina’s outburst, an echo of those burned Jewish books, written by an artist who understood in a profound way that knowledge and writing will keep being lost or destroyed and then rediscovered, generation after generation, by a people obsessed with learning and always on the march. Another beautiful articulation of this idea can be found in The Invention of Love: “Have you ever seen a cornfield after the reaping?” asks Housman. “Laid flat to stubble, and here and there, unaccountably, miraculously spared, a few stalks still upright. Why those? There’s no reason. Ovid’s Medea, The Thyestes of Varius…the lost Aeschylus trilogy of the Trojan war…gathered to oblivion in sheaves.” The mourning for a lost culture and the gratitude for fragments left behind has characterized Stoppard’s work from the beginning.

Although Stoppard did not live in the shadow of war violence and the Holocaust as Pinter did, his work inevitably deals with moral questions about what it means to live a “good life” and how one can deploy language as a bulwark against fascism, cliché, and repression. True passion in a Stoppard play always lies in thought and speech. As Young Housman tries to parse a Catullus Ode with his older self in The Invention of Love, he asks, “The point of interest is—what is virtue?, what is the good and the beautiful really and truly?” Alan Jones, Dean of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco during my tenure at American Conservatory Theater, believed that the key to understanding Stoppard was his “brilliant rabbinical method of endless interpretation,” most passionately realized in The Invention of Love, in which young Housman says, “Scholarship doesn’t need to wriggle out of it with a joke. It’s where we’re nearest to our humanness. Useless knowledge for its own sake. Useful knowledge is good, too, but it’s for the faint-hearted, an elaboration of the real thing, which is only to shine some light, it doesn’t matter where on what, it’s the light itself against the darkness, it’s what’s left of God’s purpose when you take away God.”

For all his silliness, words and knowledge have always been sacred to Stoppard. In the 1980s, when he became involved with campaigns to support dissident Soviet and Eastern European writers, Stoppard began to experience firsthand the dangerous ways in which political regimes distort language to mean its opposite—misuse of language that leads to peaceful protestors being called “agitators” at the same time that political dissidents are forced to become garbage collectors and menial laborers. One of the first jokes he heard when he went back to Prague in 1977 was “Definition of a pessimist? A well-informed optimist.” The deployment of language both as a legacy and as a mordant means of resistance has been central to Stoppard’s aesthetic and life’s work.

The disconnect between memory and the present, and the question of what can be salvaged from the ruin of the past, is as aching in Leopoldstadt as in No Man’s Land. This is probably why the characters in both plays expend so much effort avoiding thoughts of the past, while staring obsessively at faded snapshots in a photo album. “For a playwright, the relationship between the author and what is being transmitted is like a blurred photograph,” Stoppard told Hermione Lee. The past, even when unknown or misunderstood, is the most fertile of material, particularly for two outsiders who were able to write both about what they saw when they looked through the window onto the landscape of English culture, and about what it felt like to know that there was another nearly lost world behind them, waiting to be reimagined in the theatre.

Carey Perloff (she/her) is an American theatre director, playwright, author, and educator. She was the artistic director of American Conservatory Theater (ACT) in San Francisco from 1992 to 2018.