Few playwrights create a language for the stage so distinctive it cannot be mistaken for anyone else’s. Count the controversial David Mamet among them. The clipped, coarse, poetic patter of his work, commonly identified as Mamet-speak, crops up in his plays (Glengarry Glen Ross, Speed-the-Plow) as well as his film scripts (The Verdict, House of Games). Staccato fireworks spill from the mouths of characters whose verbal blood sport and power dynamics, tinged always with the threat of violence, play out against a shifting landscape of secrets, lies, hard truths, and grift. Little wonder, then, that actors are drawn to his work, as in the new Tony-nominated revival of his seminal American Buffalo, on Broadway now, and an all-female version of Glengarry, slated for Broadway next season.

But even as Mamet’s plays are frequently produced across the country, a vocal segment of the theatre community views him as seriously out of step for his increasingly right-leaning politics. His well-documented conversion from liberal to conservative, combined with incendiary, even trollish public comments he’s made on sensitive issues, have made him persona non grata among some colleagues and audiences.

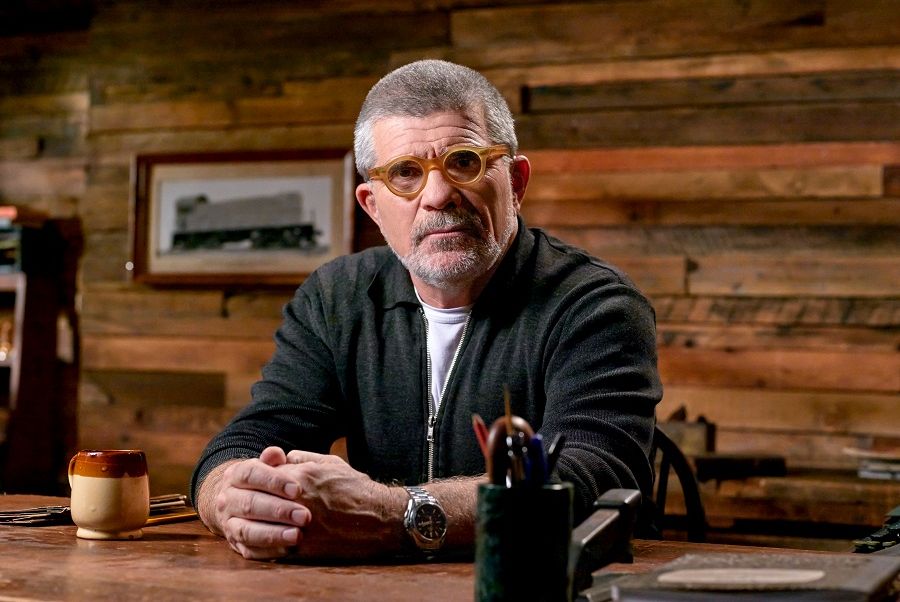

Mamet, 74, appears unfazed, perhaps in part because an informal repertory of star actors associated with his work remains loyal, despite his seeming pariah status. He also continues to enjoy the support of producer Jeffrey Richards, who has made Mamet’s work, both premieres and revivals, a perennial Broadway commodity.

In a recent interview, Richards told me that in dealing with Mamet, he steers clear of politics. “I only talk to David about his plays and work with him as a producer works with a playwright,” said Richards diplomatically. “I’ve found that I’m able to produce his plays because they’re of great merit,” adding that Mamet’s “place is secure in American theatre as one of our foremost dramatists.”

Mamet, who speaks in much the same idiom as many of his characters, is an unrepentant provocateur with a persona that, like his art, is neither pretense nor bluff. He feels no need to explain or apologize. In a recent phone interview, his idiosyncratic voice came across loud and clear. The co-founder of the Atlantic Theater Company (and its affiliated acting school), and the author of numerous books on writing and acting, as well as a number of plays published by TCG Books, continues to have strong opinions about craft, the state of the American theatre, and myriad other topics.

Speaking from the West Coast, fresh from a tour promoting his new book, Recessional: The Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch, the prolific writer has, as usual, multiple projects in the works, including novels and plays. He’s not hurting for work. It’s no surprise, then, that he doesn’t care to dwell on his polarizing reputation.

“I never stop to think about it,” he insisted to me. “Here’s my question for you: Who’s on the other pole? Woodrow Wilson said it’s easy to get the mob to agree with you—all you have to do is agree with the mob.”

Has he paid no price at all for his sharp right turn, then? “I might have paid a price, but whatever price I paid is minuscule to the benefits I’ve reaped,” he said.

Taking Stock

Mamet, who grew up on the South Side of Chicago with an appreciation for the sacred, the profane, and the Socratic method, is by turns both Talmudic and blunt in his work.

“Like with the things I’ve been writing about that concerned me or troubled me or piqued my curiosity, an artist doesn’t really write about the future, he writes about the present,” Mamet said. “The decay in American society, in American culture, has been operating for many years. If you go back to the literature of the 19th century, people said it was operating then. So a lot of the things I was writing about many years ago, the chickens have come home to roost. So be it.”

An adherent of economist Milton Friedman’s free-market beliefs and a combatant in Donald Trump’s culture wars, Mamet nevertheless views a divided America’s inability to rationally or civilly discuss its differences, much less reach compromise, as a dire warning sign.

“We’re at a cataclysm in American history, and the question is, are we going to accelerate our decline or are we going to look at our situation and emerge into a healthy maturity as a country?” Mamet asked rhetorically. “Most of the country is, however they describe themselves, centrist—a little bit to the left and a little bit to the right. But they all want to put food on the table, educate their kids, get married, have a peaceful community and be better—Black and white, liberal and conservative—because, a) it’s a command from God and, b) it makes things a little bit easier than having people screaming at each other all the time.

“The question is, how are we going to reach this middle ground? The answer is the Constitution, which is a blueprint for disparate people getting along with each other in the easiest possible way. That’s what we’ve got to come back to.”

Still, the playwright doesn’t believe that theatre or the arts have much to say about this process. “No, that’s called propaganda and agitprop,” he said. “There’s a lot of propaganda in plays in New York now about how this group is good and that group is bad, blah, blah, blah. We don’t need to have our prejudices take over the theatre. It’s a misuse of the experience. People say, what about changing people’s lives? My answer to that is, what play did you ever see that’s changed your life? That’s not the purpose of the theatre.”

If anything, Mamet puts his faith in the free-market working of capitalism to give people hope—which I told him that some see as ironic, given the apparent anti-capitalism of his iconic early plays (not to mention his once leftist offstage politics). Then, as is Mamet’s habit, he inverted the interview to make a point.

“Let me ask you question. How do you feel about capitalism?”

“I resent it,” I said, “because it doesn’t reward writers very equitably.”

“Well, let me ask you a question. When they pay you for your work, do you accept the check?”

“I do.”

“Then the next question is, would you like to get paid more for your next job?”

“Of course.”

“Okay, so you’re all in favor of capitalism. Me too. All the people screaming about capitalism, including the ‘voice of reason’ in Congress and all of these actors, they all pick up the check. That’s capitalism,” Mamet continued. “Here’s the thing: You can scream about how bad capitalism is in our society, but if you scream about how bad communism is across the street they kill you.

“My plays are not an indictment of capitalism. One can easily say King Lear is an indictment of capitalism because, look, he’s the king, but he gave up a little bit of power and everybody else wanted to be the king, so they took away all of his servant men. Nobody hates capitalism. Even the people screaming about it are doing it for what they can get out of it, because that’s how human beings live. The alternative to capitalism is slavery, in which case you don’t have to worry about it. But the only problem with slavery is you’re a slave.”

Mamet’s tendency to make swaggering, sweeping statements which mirror the terse, incendiary dialogue of his plays can be, as critics note, reductive rather than revelatory when applied in conversation or in his nonfiction writing. But the polemicist and dramatist in him always seem ready for a rhetorical scrap.

Push and Pull

Mamet drew particular ire with recent comments he made on Fox News, in the midst of a right-wing campaign against alleged “groomers” that underpinned Florida’s recent so-called “don’t say gay” bill, that teachers “are inclined to be pedophiles.” When I pressed him on that comment, he doubled down, though with a slight clarification.

“Well, I stand by everything I said, because I said it,” he said. “I would say it a little bit differently. I would say that pedophiles are inclined to be teachers, and that’s true because I’ve met them myself. All of my daughters who went to public schools and private schools met them. That’s just the truth. It’s always been a part of education.”

Some wonder how he squares this slur with the action of his play Oleanna, in which a female student incites a male teacher to violence by alleging non-existent sexual harassment on his part. “The play Oleanna is about an incident between a teacher and a student,” Mamet replied. “It’s a tragedy. You have two protagonists involved, each one of them acting from what they consider the best possible motives, and they end up destroying each other. That’s what that play is about.”

At last Mamet interjected, “Now, do you want to talk about the theatre or do you want to talk about politics?”

“Let’s talk theatre,” I affirmed.

“Let’s do that then,” he said.

Even on this subject, though, it’s hard to avoid contention. For one thing, many contemporary reviews have complained that his recent works lack the sharp intellectual edge of his earlier plays.

“I stopped reading them decades ago,” he said of reviews, “because when they’re good they’re never ever good enough, and when they’re bad they’re devastating.” Indeed, the author has dismissed both critics and opponents as purveyors of “group-think” and the “woke agenda” who cannot abide his nonconformist ways.

Another theatrical topic, another controversy: There’s the apparent irony that this champion of free speech, who has complained of liberals impinging on the rights of dissent, expressly prohibits talkbacks following staged performances of his work, on pain of a $25,000 fine. What’s that about?

“It’s called a contract,” he deadpanned. “It’s an obscenity to have talkbacks, because what it does is it turns the play into an English class. And the actors should not be put in a position, nor the director nor the playwright, of defending their work. There’s a reason there’s a curtain in the theatre. The curtain comes down, and, as Shakespeare says, ‘You that way, we this way.’”

The place for open discussion, he insists, is in a bar or restaurant or at home, not in the theatre. “An artist really has nothing to say to the audience other than communicating through his art,” Mamet said. “That’s it. The talkback is a terrible misuse of the theatrical experience, which has been, like many things in life, taken over by zealots.”

Against the Method

What keeps in him in the game, then? Well, for one thing, the list of actors who repeatedly want to work with him, and vice versa, is long and distinguished. Jeffrey Richards confirmed that performers still covet the opportunity to say his words.

“I think one of the most exciting and challenging elements of being in a David Mamet play is that he has reinvented, in a sense, language for the theatre,” Richards said. “There is a certain rhythm that an artist has to adapt to be able to bring to light these very vivid personalities in David’s plays.”

The Mamet style isn’t the exclusive property of a generation or type of actor, as witnessed by the diverse personalities and approaches represented in this current revival of American Buffalo with Laurence Fishburne, Sam Rockwell, and Darren Criss. But Mamet, who has written about acting and has directed onstage and in film, can’t resist casting even this topic in oppositional terms.

“What I’m looking for in an actor is the knowledge and the courage to stand still and say the stupid fucking words, because when one does that and one has talent what you get is greatness,” Mamet said. “That’s when the real individuality of the actor comes out. It’s not what they can do with the script or to the script, it’s can they say the stupid fucking words without manipulating them.

“To do that you need a couple of things,” he continued, sparking to the subject. “You need the knowledge, the understanding to stand still and the technical ability to speak, and then whatever talent you have—and who knows what talent is, that’s why they call it talent—will come out. What comes out is not the actor’s thoughts but their soul. If they can act, they can do any play that I wrote or any play that anybody else wrote.”

Mamet has famously disparaged the Method as it’s commonly understood, including in his book True and False. “I went to the Neighborhood Playhouse School in New York. Sanford Meisner was my teacher. Lee Strasberg was across town. They both came out of the Group Theatre, which came out of psychoanalysis. They had the greatest possible aspirations for theatre—how to bring to life to an actor working under imaginary circumstances—but they had no idea how to get there, because their idea was it had to do with feelings, and acting has nothing in the world to do with feelings. Zero.

“So actors who haven’t been to school to learn to use their feelings but have been trained to use their voice and their body—that’s the pool you want to appeal to.” The actors he came up with in Chicago in ’70s, he said, including Joe Mantegna and William H. Macy, “hadn’t been to school, they just showed up and said, ‘Okay, I can figure this out,’ and as they did it, they got better, and I’m very indebted to them.”

Though dismissive of or reductive about certain acting technique traditions, Mamet draws on many established influences for the aesthetics he espouses. He and Macy co-founded the Atlantic Theater Company in 1983, where they developed what they call the Practical Aesthetics acting technique, based on the principle that the actor’s primary challenge is to bring to the stage “the life of the soul,” and that the purpose of every element of a production is to simply, truthfully tell the story. The Atlantic Theater Company Acting School teaches the same straightforward acting principles.

As for how conscious he is of his own style, he said, “You know, I don’t have any choice. People say, ‘I want to write like you,’ and I say, ‘Why don’t you write like you?’ Miles Davis once said it takes a long, long time to sound like yourself.”

Influences on his own writing abound.

“I’m very grateful for inspiration. I was talking to a friend who’s in the Special Forces, where they do all this incredibly stringent physical training. He said the best benefit of it is that it trains your mind to break down your preconceptions about what you thought you were capable of. That’s what I find one of the wonderful things about inspiration—in my case, very much Chekhov, Pinter, and Beckett—is that it imprints on you the idea of what you might be capable of if you put your mind to it.”

Where Theatre Grows

As for the state of theatre, Mamet is not sanguine, but he’s also not overly nostalgic.

“I look back over a 50-year career in the theatre at the things people were yelling bravo and hosannah about five decades ago, and most of them are unwatchable, and the same is true of literature,” he said. “Go to used book stores, if they still exist, and you look at the books published to great praise by well-known, renowned authors—I mean, I wouldn’t use them for confetti.”

He does, however, think something crucial has been lost.

“The theatre grows in bohemia,” he said. “That’s the only place the theatre can grow. It can’t grow at a university, and it certainly can’t grow on Broadway. Bohemia only takes place in the cities, where you have the intersection of ne’er-do-wells and outcasts. There’s a wonderful book called Terrible Honesty by Ann Douglas that is a sociological history of New York in the ’20s. It said what happened to the music, dramatic, and literary scene then was the intersection of the Jewish world, the Black world, and the gay world—all these different worlds of outcasts in New York that learned from each other and gave rise to a wonderful social energy. As the cities die because they’re no longer any use, there’s no more bohemia anymore. There’s no more garage or storefront theatre.”

Theatre, he said, “is for young people who demand, ‘Let me in there, I’m never getting out,’” adding, “That’s the only way to get into the theatre—you can’t get into the theatre by going to drama school and getting praise for doing a production of Peer Gynt where everyone’s a fucking potato.”

Asked about demands for theatre to become more equitable and representative, Mamet sounds like, well, Mamet.

“I don’t know what equity and inclusion means, and I don’t know if anybody does,” he said flatly, then added, “Here’s what I think: My Black brothers and sisters in the theatre for 150 years were excluded from full participation, so it’s wonderful, it’s great they’re being included.”

While it’s hardly intended as a nod to gender diversity, let alone #MeToo, the prospect of an all-female Glengarry does at least transfer the piece’s agency to women. It’s not the first time an all-female Glengarry has been tried, but when Jeffrey Richards came to Mamet with the idea to do it on Broadway, Mamet said he told him, “It seems like a stunt, but okay, if it’s going to put ceviche on my luncheon table, I’ll certainly vote for it.”

An all-women Glengarry was set for a Broadway production in early 2020 when the pandemic hit. Richards put the project in mothballs until this year, when an April 12 reading was held at New York’s MCC Theater with Patti LuPone, Felicity Huffman, Rebecca Pidgeon, Rosie Perez, Renée Elise Goldsberry, and Yolonda Ross. The consensus was that the play transcends gender, and that in this staging, the toxic masculinity audiences associate with the piece may require a reset of expectations.

“We realized it didn’t make any difference. It was just fucking great,” Mamet said. “You could play that play in masks. Any good play you could play in masks. Any good play you could do on the radio so that somebody’s race or gender, thank God, won’t make any difference, because we know we’re listening to a story.

“We were all blown away,” he added. “The reason we were all blown away is that it wasn’t a stunt, it’s actually a great idea.”

“It was indeed a very successful reading,” said Richards, adding, “I’m hopeful that we will be able to put together a stellar company and I’m hopeful it will include some of these artists. It’s at least a year away, I think, maybe sooner. We’ll see how everything comes together.”

For an Encore

Though he’s not asking for a pass back into polite theatre society—the hostility seems to be mutual—Mamet insists it is not his intent to stir the pot through his work.

“My job is writing an entertainment to the best of my ability,” he said. “It might be a farce or a comedy of manners or a tragedy, or a drama-comedy. It’s an entertainment. It’s not my job, though it may be the result, to stir up people’s feelings.

“People tend to forget in the age of mass entertainment that art, and the two major sub-categories of drama, tragedy and comedy, really comes out of religion. Tragedy just means we’re all flawed, but there’s an underlying order in the universe which you can violate at your own peril. Comedy just means we’re all flawed, but there’s an underlying order in the universe that’s going to come and save us at the last moment and restore us sadder but wiser to the status quo.

“When art starts getting divorced from religion, and entertainment starts getting divorced from art, all that we’re left with is convention. If you look at almost all movies these days, all it is is convention, either with special effects or with sex. The problem with that is they’re all the same. I mean, after you get done showing nakedness and people copulating and doing it in groups, then what? After blowing up one building, you blow up two buildings, then you blow up the world, what do you do for an encore, as my dad used to say?”

Health permitting, he expects to keep churning out ever more new work across mediums.

“I like to write,” Mamet said. “I mean, what else am I going to do all day? I can do three things, right: I can read, I can take a nap, or I can write. If I do them in a rotation that’ll fill up the day pretty quick. I have too much self-respect to learn how to play golf.”

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance writer and the author of the 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.