Discovering, owning, and expressing one’s own identity constitutes perhaps the scariest yet most validating process humans undergo. And now more than ever, that identity can be complicated, contested, fluid. Where does identity come from, and how does it take shape? According to Asian American actor Jodi Long, it’s rooted in a web of influences, what she calls “imprints”—some stemming from our DNA, some from emotional relationships with parents, others foisted upon us by society.

Long, 68, is most widely known for her television work, in memorable roles on All American Girl, Café Americain, and Sullivan and Son. For her role as Mrs. Basil E in the Netflix rom-com Dash & Lily, Long won the 2021 Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Daytime Fiction Program, becoming the first Asian American to capture the prize in that category. But Long started her career as a stage actor, appearing in numerous Off-Broadway productions and five Broadway shows, beginning with her Main Stem debut at the age of seven in the Sidney Lumet-directed 1962 musical Nowhere to Go But Up. It is to those theatrical roots that she is now returning with her new one-woman show, American Jade, running at Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, Pa., May 20-June 11.

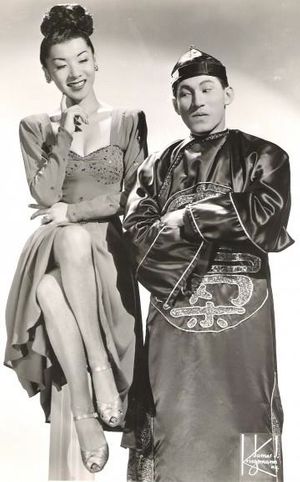

The autobiographical show, written and performed by Long and directed by Eric Rosen, reveals her grappling with the imprints that formed her identity. Central to the story are her Australia-born Scottish/Chinese father, Larry Long, and her Japanese American mother, Kimiye Tsunemitsu. Billed as Larry and Trudie Leung, they were nightclub entertainers in the 1940s and ’50s. Long’s father went on to perform in the original production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song, which was noteworthy as the first Broadway musical to feature a largely Asian cast, though it was criticized for its stereotypical renderings of Asian characters. Forty years later, Long experienced a profound “full circle” moment when she was cast in the 2002 “revisical” of the show, in a substantive rewrite of the book by David Henry Hwang.

I spoke to Long earlier this month via Zoom about her connections to her parents, her identity as an Asian American actor, and the barriers performers of color continue to encounter in the theatre field.

LISA JO SAGOLLA: What’s motivating you to present this very personal theatrical work now?

JODI LONG: I actually started writing this play in 2000. It was just a way for me to put down stories that I felt were important to get out there, because no one really had stories like my parents’ stories. And I knew if I didn’t write them down, they would be lost. By 2002, I had a first draft. But I was doing the Flower Drum Song revival at that time, and a writer friend of mine said, “You have an incredible story in your family history with that particular musical,” and suggested doing a documentary. She was a Caucasian woman, and an accomplished screenwriter, but the people who were doing financing for projects like that would say to her, “Why are you doing this story about Asians?” When she realized she wouldn’t be able to finish the film, she gave me all the wonderful footage she had taken with my parents.

It sat in my closet until, one day, I happened to run into Christine Choy at a memorial service in New York. She’s the Academy Award-nominated director of Who Killed Vincent Chin?, that documentary about the man who was murdered because they thought he was Japanese, though he was really Chinese American. I asked her, “Hey, are you still making films?” By then she had become a professor at New York University, but I sent her my footage and she was interested in my story. She and I were able to raise some money, and we made the documentary together. I ended up writing it. It’s called Long Story Short, and it won the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival in 2008.

But the play has its own evolutionary process. To answer your question as to why now, it’s because now I can be more frank. Both of my parents are dead, and I can really delve deeper. I did a lot of workshops of the play over the years, and it really evolved as I grew and became a better writer. Also, I don’t think this country was ready for this play 20 years ago, but with all the new awareness about experiences of people of color, the stories we have to share, and, unfortunately, all the terrible Asian hate that went on during the pandemic, I think now is the time.

You chose Eric Rosen to direct you in this play. Why? And what impact has he had on its evolution?

I was so impressed with what he did in developing the Kansas City Repertory Theatre when he was artistic director there. He’s not only a creative director and playwright, but he understands the business side of actually getting theatre going. And I’m really interested in that—in how we cultivate the next generation of theatre artists so they can create challenging and inspiring work in a way that’s sustainable. So I called him up. I invited him to meet me for coffee and he just started asking me questions. A lot of those questions turned into writings that are now in my new play.

For example?

I started telling him how I felt about this incident that occurred when my parents were not together, and I had to wait for my father to pick me up downstairs in a cold vestibule because my mother wouldn’t let him into the apartment. Eric told me it was a fascinating story and that I needed to write it down. And there I was, all of a sudden, going so much deeper into my experience of being a child of a vaudevillian entertainer who was pretty self-centered. My dad came from that era of performers like Mickey Rooney; they were always “on.” I would roll my eyes as a kid when he would be telling stories and always had to be the life of the party. So it was interesting when I started to write about how I really felt. I was a daddy’s girl—I love, love, love my dad. But there were definitely issues between us.

I understand your parents were headliners on what came to be called the Chop Suey Circuit, a network of nightclubs, mainly in San Francisco and New York, that presented acts by Asian American entertainers. And your parents also performed in USO shows, at New York’s Palace Theatre, and on Ed Sullivan’s TV program in 1950. Can you describe their act?

I always tell people it was sort of like Stiller and Meara with tap dancing and singing. It was something I did not want to talk about when I was a kid, because I thought what my parents did was really corny. I was really young when they were playing the clubs. But I was backstage all the time, and I was very impressionable as a child, so I do remember certain things vividly, particularly about the Forbidden City. That was a club in San Francisco, and that’s all reflected in the play.

My parents really broke barriers. They played a lot of clubs in the New York Tri-state area and were typically the only Asian American act on the bill. And I think they were the first Asian American husband-and-wife team to perform on Ed Sullivan’s show, and they were doing comedy, song, and dance, not spinning plates.

You make such an important point, about the stereotypes associated with Asian American entertainers back then, and even now. Just yesterday, when I told a friend of mine I was interviewing someone whose Asian American parents had performed an act on the Ed Sullivan show, her immediate response was to tell me how fondly she remembered watching “those Chinese acrobats.”

Yes, I think that casually racist thing still comes up so often and in different ways. Many people are completely unaware of that unconscious bias and the assumptions they make. Yet those are part of the imprints that make us who we are. Everyone is affected by them. But if we can, we go beyond them.

Having spent your childhood backstage, on the road with showbiz parents, did you always want to be a performer yourself, or did you ever consider pursuing a different kind of career?

I always drew myself onstage. You know, when kids are four or five years old, and they draw policemen or nurses, I drew a picture of myself right in the middle of my parents on a stage. My mother did not want me to be an actor because she saw how hard it was for my dad, never knowing what your next job would be. But my dad felt you had to do what you love. For a brief time when I was a teenager, I thought I wanted to be a lawyer. So I went to a performing arts high school, thinking I could get higher grades there and get into a better college. Instead I ended up getting hooked on acting.

After you graduated from the intensive, conservatory-style acting program at Purchase College, what happened?

It was really hard to get seen for roles. Things were very difficult then for Asian American actors. Now, since Hamilton, there’s a whole generation that wouldn’t care if George Washington was played by an Asian. But back when I first got out of college, I’d go to an open call for a play, say Our Town, and when I walked in, they’d say, “What are you here for?” and when I said Emily, they’d say, “Oh, we’re not doing it like that.” I would say, “Like what? I’m young enough to play Emily.” But they wouldn’t audition me, and I would just leave. The problem is, you can’t get better as an actor unless you work. I wanted to keep up my craft, so I did a lot of regional theatre. We really felt in my day that to be a good actor you needed to do theatre work first, then you could go do film and television.

In the late 1980s there was this wonderful National Symposium on Non-Traditional Casting held in New York. There were panel discussions among theatre professionals and lots of famous actors did scenes showing them in roles they wouldn’t normally be cast in. James Earl Jones did a scene as Big Daddy from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. I did a thing from The Dining Room. During that time I got the chance to play Cherie in Bus Stop and Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday. We really thought it was the beginning of a big change. But it wasn’t. It was just us showing we could do it, and then theatres went back to casting the way they always did. Things are starting to change now, thank goodness, but it’s taken a long time to get to this point.

Lisa Jo Sagolla (she/her), a New York-based arts critic, is the author of The Girl Who Fell Down: A Biography of Joan McCracken and Rock ’n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s. She teaches at Columbia University’s Teachers College and Rutgers University, and is currently researching a chapter on the Broadway musical Timbuktu! for a new book on Geoffrey Holder.