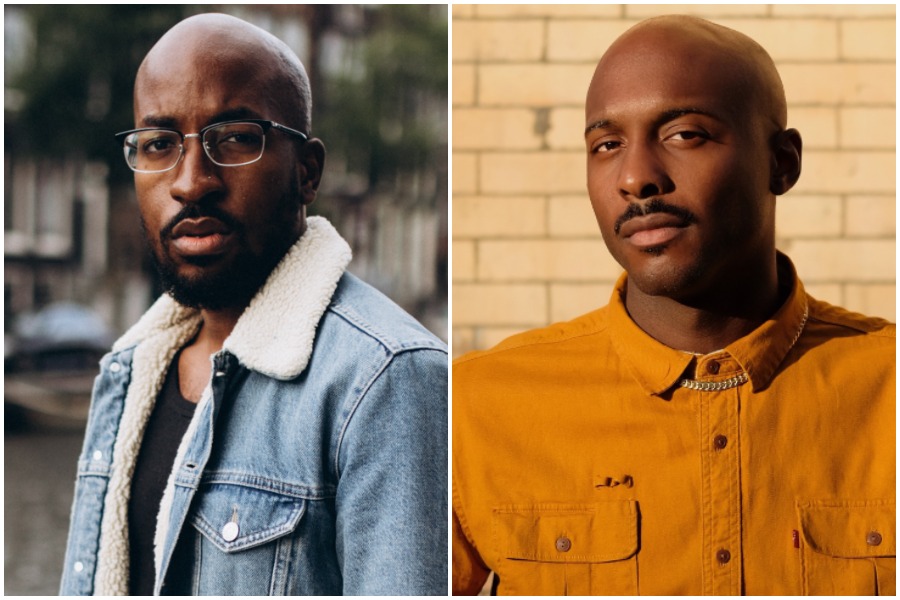

Dave Harris and Mansa Ra first met in New Haven, Conn.; both were in Donald Margulies’s playwriting class at Yale, and both taught playwriting units at Co-Op High School there. Now they’re back together in the same building again, each with a new play at the Roundabout Theatre’s Off-Broadway space, the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, where Harris’s Exception to the Rule just opened downstairs at Roundabout Underground, and Ra’s …what the end will be is in previews upstairs at the Laura Pels Theatre (opening night is June 2). Their plays have little in common: Harris’s depicts six Black high school kids sparring and bonding in a seemingly endless detention, while Ra’s is a drama about love and loss among three generations of gay Black men under the same roof. But in a recent conversation over Zoom, the two writers found some common ground in their parallel journeys and ambitions, as both come from tight-knit communities that have supported their dreams and inspired their writing, and both have alternately struggled and succeeded in building similar networks of support and connection in the predominantly white theatre field.

Harris recently had Tambo & Bones produced at Off-Broadway’s Playwrights Horizons, and Ra’s last New York production was Too Heavy for My Pocket, also at the Roundabout. If the dialogue in their new plays flows freely and thoughtfully as this conversation, audiences should be in for a treat.

—Rob Weinert-Kendt

Mansa Ra: I think it is wild that we are two Black people under the age of 50 who have spent a significant amount of our time writing plays. It is not a career trajectory that I planned on. I guess I was just curious, when did you accept, “Yeah, I’m a nerd, I write plays”?

Dave Harris: It’s funny, because my answer ties very directly to why I wrote Exception to the Rule. I grew up in Philly and we had this group called Philadelphia Young Playwrights that a bunch of Philly playwrights came up through. Like, Quiara Alegría Hudes was a part of it—she brought us to see In the Heights when I was in middle school. So I spent most of my middle school and high school reading and writing plays, but never thought it was going to be a thing. I went to college and thought I was going to be in the sciences. No one in my family had done the four-year college experience, so I was like: if I go to college, I have to do something that sounds legit. I’m gonna work in a lab because you can’t fuck with that.

Mansa: Right? No one asks follow-up questions about a job in a lab.

Dave: I thought, this will be the path out of generational poverty. Halfway through undergrad, I had a teacher, Deb Margolin, who slapped me upside the head and was like, “All the people in your life didn’t work as hard as they did for you to go off and do something that you don’t love.” And it kind of hit: So many people in my family work from a place of fear and not from a place of desire. And if I’m going to take all the things I was born toward, whatever luck and institutional support I’ve been able to have that people in my family haven’t, the only way to really change the trajectory would be for me to pursue something that I love. I’ve watched so many people in my family not get the chance to do that, and end up living whole lives working just to keep the landlord away. So if I can build a life where I have the luxury to not do that, then I have to relentlessly pursue it as far as I can.

Mansa: Wait, Dave—you wrote your first play in middle school? And now, being the amazing playwright that you are, you are living a career without fear?

Dave: The fears that I had growing up, I don’t have any more. At least practically. I remember the first time I went grocery shopping and wasn’t looking at the price of every single item. It’s absurd to me that that’s come through writing.

Mansa: That’s incredible. I get so annoyed when young people are told, “Don’t pursue a career in the arts, there’s no money in it.” It’s absurd. I was just at the Laura Pels Theatre today, and there are so many people employed who are building and painting the set—that’s a career in the arts. It’s amazing that you got the right advice so early.

Dave: How do the people from home interact with your career and your work? That’s the thing I feel like I’m always battling; it’s like all my writing exists far from the place that I grew up in, and my family have so much distance from this world. So I wonder for you, with your second play at Roundabout, do you feel that distance?

Mansa: I’m a second generation college student, which is to say, me and my mom were the only ones with degrees in my family. That by itself creates distance. When I got into Yale, my grandmother was like, “Oh, that’s so good, baby…That’s up north somewhere, right?” Not that she didn’t care, but it just isn’t a part of her world. So when I went to school, it was important to me that my first play was for my grandmother. The same way you said that our families didn’t sacrifice and work so hard for us to not be pursuing our dreams, but also not for our lives to be disconnected from them—we are a part of their legacy. So everything I write, I make sure that my community will enjoy it.

I’ve gotten some criticism for that. More than a few of my friends have told me that my plays are really polite, soft, or kind of downplayed. Y’all, that’s because my grandmother doesn’t curse. I’m always writing for my community, even if they have to save all year to come see it—which is usually the case. My uncle came to see my play and the cab from JFK to Harlem was 100 bucks. He was so shook, but I was like, “That’s how much it costs, bruh.” I don’t take their investment for granted. My plays can’t get too far away from my family, because they matter too much to me.

Dave: Yeah, I was getting my family to come up to see Tambo & Bones and it was like, “Okay, here’s money for the Uber, here’s for the train, hotel”—it’s so many steps. I can’t wait to eventually get it to play in Philly, where I can just be like, “Yo, y’all can come through there.”

But I think a lot of my writing comes from a sense of community, and also a sense of contention with community. One of my first professional play readings ever was at the Great Plains Theatre Conference for my play White History. I remember when the play was over, this older Black director stood up and was like, “I’ve never been more offended in my life. I spit on this play,” and then he mimed spitting on the ground. And I was like, “Oh shit, it’s about to go down!” So yeah, out the gate, much of my writing is battling to deeply complicate and push against a dominant narrative within a community to reach someplace new.

Mansa: I was literally just about to say that what I love about your work is that it is always so clear about what community it is being performed in front of. The work is meta, sometimes really directly, sometimes not very directly, but it always takes a stand. I just assumed that’s from slam poetry. Your essay about what it meant to be a slam poet making art about pain was so moving. What did you do? Did you flip him off or something?

Dave: Oh no, we just went back and forth in the talkback. And honestly, I kind of love that. I hope to upset my own truths in order to write. There are some plays that empower and construct a truth to be agreed on, and some that unsettle. I think they’re both worthy things in theatre. Of your plays, I’ve only interacted with …what the end will be and Too Heavy for Your Pocket, and I think there’s something so huge about them. They have a classical structure that can both hold a kind of “universal” experience, but also are so specifically for the community you see. That’s a special thing. Roundabout has its own history, and to build that space where it’s like, Hey, this is where we can sit in the space and feel both challenged and held—that’s a remarkable gift.

Mansa: People are paying way too much money and sacrificing too much of their time to sit in the audience for me not to do that. I’m glad you brought up Roundabout’s history, because I want to talk about it. I will share a story. I was talking to a mentor early in my career, and I was telling her, “I’m really excited about a reading coming up at the Roundabout Theatre.” And she said, “Oh my God, that’s amazing—I didn’t know they did anything other than white plays.”

Dave: I had an interesting realization with Miranda Haymon the other day: I voice-memoed them and was like, “I think these are the first two plays at Roundabout that are about Black people in the 21st century.” Which is not a judgment specifically on Roundabout; the American theatre loves old-school Black people. Even in TV and film too, the number of period pieces and biopics I am offered to work on is outrageous. Like, we’re doing this again? I mean, I’m so happy that Alice Childress is having a moment right now. I’m obsessed with literary lineage. But there’s a certain element of it where we’re producing a comfortable Blackness, a very familiar Blackness. I think we’re more adjusted to seeing a kind of Black struggle narrative. Which is valid, but also it’s exciting to me that our plays are bringing two very different 2022 ideas of Blackness into the space. I think new play artists like Miranda have been championing that too—they have been with the company for so long and have such artistic and administrative skill that we’ve been able to build an incredible artistic home on this production at Roundabout, and it’s been so supported by the theatre.

The interesting thing for me is that Exception to the Rule is—it’s kind of a hood-ass play. I wrote it very much with the kids I grew up with in mind. And so we’re bringing in energy where we’re like, we’re gonna curse every other word, we’re saying nigga every other word. For us, it’s more about, this is really fun; we’re actually getting to embrace the side of us that we very rarely get to play. One of our actors talked about how the characters he gets to play on TV almost always wear suits, and this is the first time where he gets to be like: I’m remembering who I was in high school, to perform in a language I don’t often perform in. I think that’s interesting to do in the context of white patrons, but also has been a fun experiment for us to make the space inside the room as much for us as possible, such that no matter who is in the audience, we actually can just feed off ourselves. I don’t take any audience for granted, but that’s part of the fun and the chaos.

Mansa: I love that. The very first line of …what the end will be is Keith Randolph Smith shouting, “Nigga, you just gon’ leave me out here?!” It was an intentional and empowering choice, inspired by Toni Morrison—the first sentence in Paradise is, “They shoot the white girl first, with the rest they can take their time.” It takes audacity to be authentic.

Especially in a space like the Roundabout, which I think has been really a culprit in so many injustices. When I read the We See You White American Theater demands, I had a realization: Roundabout does none of this. Conversely, the Roundabout has an abundance of resources. Like you said, the kids in your play get to be as musical with a profanity as they want. Who gon’ check me, boo? Literally no one at this white-ass theatre.

Dave: Each of my plays is responding to the last one, so it’s always fun for me to build the next complication. Exception to the Rule is about this character who is having a battle—if “success” means getting away from your community, what’s the cost of staying home, and what’s the cost of leaving? I feel like a lot of Black playwrights have mirrored that trajectory: So many of us come from a specific place and then end up in various institutions, whether that’s undergrad or grad school, or the American theatre and beyond. But when we’re in front of white audiences all the time, does that then affect how we write or doesn’t it? …what the end will be was a commission from Roundabout, right?

Mansa: Yeah, it was.

Dave: So for you, when you were building it, knowing that the next step would be the Laura Pels Theatre, was that folded into it? Was it, “Oh, I have a story I want to tell for my community,” or was the idea of doing it at Roundabout a part of it?

Mansa: What rings true in what you just said is each play responding to the last play. …what the end will be is 100 percent responding to Too Heavy for Your Pocket. So after two years of riding that wave, I wondered about the exact opposite direction? What is the furthest thing I could tell from this beautiful family drama set in Nashville, Tenn., in 1961? Hmm. Maybe a gay Black family today, in the heart of COVID.

Also I have to say: I negotiate fear a lot when I write. I’m frequently scared by my art. I’m not an extrovert like you.

Dave: Interesting, do I read to you as an extrovert?

Mansa: Dave, you’re a total extrovert! For me, the fun about being a playwright is I can get the the actors to do it.

I wanted to tell an explosive drama for the Laura Pels Theatre that doesn’t have to be rooted in any degree of naturalism, that doesn’t need to be historically accurate, or that it makes my grandma feel good. It was really just: If how can I make myself and my communities proud? That was the real endeavor for the piece.

Dave: Also it’s seeing the full lineage. I know that’s kind of built into the structure of the family play, but I remember when I read the script for …what the end will be, I was like, Oh we’re getting the full patriarchal lineage of this family onstage at the same time. That sort of generational dispute—there’s so much to navigate within that, and that’s what I find exciting about your play, that we’re going to watch father to son, father to son, with so many different lenses.

Mansa: Oh, thank you. I just have one more question. You and I are just so young. We have decades of storytelling ahead of us, God willing. In 40 years, when we talk again for the press, what do you hope your legacy in this industry will be?

Dave: I have the exact same question about legacy on my list for you. I am obsessed with lineage. In grad school we would pick a playwright and read their first produced play, their most recently produced play, and two plays from the middle to see if we could map not just what’s shifted in their craft, but also, what’s shifted in their world? Are they doing the thing where their plays are responding to each other? How does having multiple productions affect the way you write your next play? The thing that’s always excited me most about theatre are the playwrights where I feel as if I’m going to spend my entire life chasing them. Those for me are the ones who every single play feels like it could have been written by a different writer. I remember, I saw An Octoroon at Theatre for a New Audience and was like, “Oh, that’s the bar.” Then I remember reading all of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s other produced plays, and I was like: Oh my God, these are all so structurally unique. Each one tries to push a different formal boundary. Same with Julia Cho. Same with Anne Washburn. So if someone watches a play I write 40 years from now, and then reads Exception to the Rule and then Tambo & Bones and is like, wait, they’re the same person?! I would love that.

One of the questions on my list for you was how you track your literary ancestors. Who are the writers you’d say you wouldn’t exist without? And then, projected into the future, what have you built?

Mansa: Beckett, Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison, Tarell Alvin McCraney—those are the godfathers and godmother whose scope inspire me. They can put scope into a stunning grain of sand for you.

My life goal is to have a Vegas-style revue in the Memphis Pyramid, so Memphis city school students who are brilliant poets and playwrights are able to do that at home. I think it’s a crying shame that we have to travel to the Great White Way in order to be our best selves as Black people. By the end of my career, I would love to at least set up one more trade route in the Chitlin’ Circuit of the 21st century.