NEW YORK CITY: It’s the end of an era. Theatre Communications Group (TCG), the national organization for theatre and the publisher of American Theatre magazine, has announced that founding publisher Terry Nemeth will retire in the fall. A search for his successor is currently underway.

For almost 40 years, Nemeth has led TCG’s publishing programs, including TCG Books and American Theatre magazine. TCG Books has grown to become the largest independent trade publisher of dramatic text in North America, with a catalog of nearly 500 titles, including 18 Pulitzer-winning plays (soon to be 19, with the coming fall publication of James Ijames’s 2022 winner, Fat Ham). As the nation’s essential magazine for professional nonprofit theatre, American Theatre has been providing theatre professionals, students, advocates, and audiences a comprehensive journal for more than 30 years. A search process is now underway to identify a successor, and Nemeth will be honored at the TCG National Conference in June 2022 in Pittsburgh and online.

“Terry founded TCG Books on the conviction that plays are literature and worthy of the same resources, respect, and critical attention as any other literary form,” said Teresa Eyring, executive director and CEO of TCG, in a statement. “So many playwrights and authors have been impacted by Terry’s kindness, commitment, and business acumen. He is beloved, both within TCG and the theatre field, and we look forward to continuing his legacy of championing plays and playwrights.”

In a statement, playwright David Henry Hwang enthused, “Nobody has done more to keep play publishing alive in America than Terry Nemeth. He has ensured that our plays can be read around the world and by future generations, and that we would be paid for our work. I’m sad to see Terry go, but I am grateful for his legacy, which brings me joy.”

Playwright Lynn Nottage added in a statement, “Terry has been such a nurturing, supportive, passionate, and important caretaker of the work of playwrights. Over the years, he has championed our plays and ensured that the work continues to have a glorious literary life beyond the stage. His commitment to publishing and amplifying plays of both emerging and established playwrights is unparalleled, and there are generations of readers who have gained access to our work because of Terry’s vision and advocacy.”

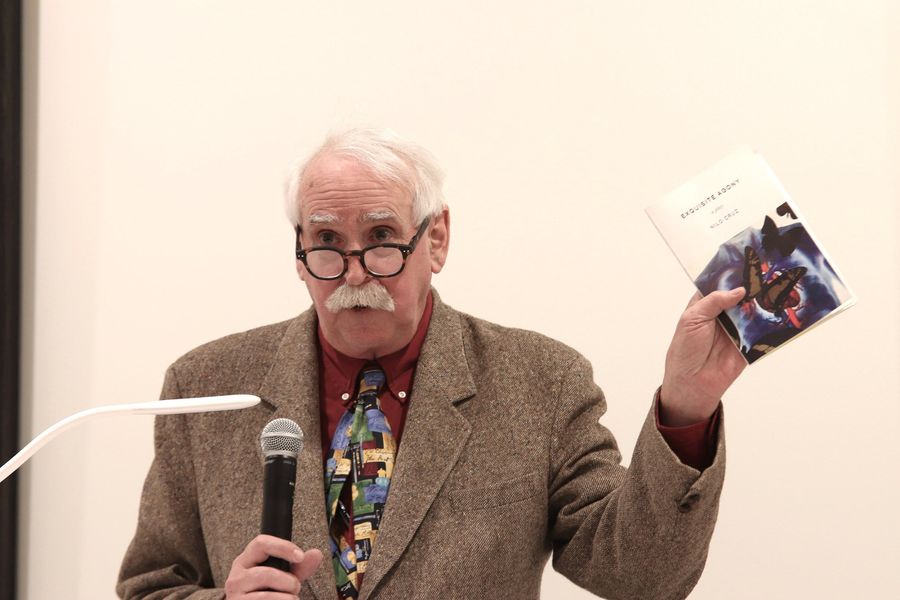

Nemeth, who won an Obie for play publishing in 2003, is a Long Island native and proud grandfather. I spoke to him earlier this week about his extraordinary career in publishing, both before and at TCG.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: How did you get into publishing? Was it always your dream to make and sell books?

TERRY NEMETH: Well, I thought I was going to be a writer. I won the high school poetry prize and edited the high school literary magazine. Then in 1968, I dropped out of college and hitchhiked to San Francisco. I got a job in a bookstore there called Paul Elder, an old carriage trade bookshop, a beautiful old store. They were just bought by Brentano’s, and had just bought a new space up the street where they were going to bring in paperbacks for the first time, and I got to spend my first two months working in this bookstore, receiving every paperback book ever published in the United States: every New Directions book, every Grove Press book, every Doubleday paperback, every Vintage.

Were you already a book lover?

When I came to San Francisco I had two books in my backpack: Cold Mountain poems, and The Dharma Bums. I was a big Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac fan.

Was there something special about the Bay Area publishing scene in those days?

Oh, yes. I became manager of the paperback department and had five people working for me. But I and my assistant got really pissed off at the manager of the whole store and quit two days before Christmas. Then I got a job at Bookpeople in Berkeley in February of 1970. Bookpeople was a book distributor, and their claim to fame is they were the only source for the Whole Earth Catalog, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive—all the counterculture books that you could possibly imagine were in one warehouse on University and Seventh Street.

Did you carry Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book?

No. You know, one time when I was in Brentano’s, Abbie came into the store and dramatically stole a book from me. And I just thought, “I don’t fucking care, you do whatever you want to do. I’m not gonna be your pawn today.”

How did you go from book-selling to publishing?

At Bookpeople I was in charge of all the small press distribution, so I worked with a couple of 100 different small publishers: Don Allen at Four Seasons, who had Gary Snyder, Richard Brautigan, Lew Welch, Robert Creeley. Lawrence Ferlinghetti would drive over in his Volkswagen and deliver books on our receiving dock, because he didn’t want to pay the freight from San Francisco; he had his little poodle in the front seat and he would load the books on the dock. I worked with small presses—my job was to help them get their book in the best shape possible to sell the bookstores. And with three other people we started our own small publishing company, Mudra, a literary letterpress. We published Robert Bly, Robert Creeley, David Meltzer, lots of good stuff. About the same time, Bookpeople decided to start their own publishing company called Wingbow Press, and our first book was Alcatraz Is Not an Island, which was written by Indians of All Tribes, who had occupied Alcatraz Island.

Was it a good business at the time, or was it more of a labor of love?

When I left Bookpeople there were probably 50 people working there. It was employee-owned because we had gone on strike. When the original owner took part of Bookpeople and then sold the Whole Earth Catalog to Random House, which was like 30 percent of our business, we went on strike and bought the business from the owners, and we became an employee-owned company. Everyone who worked there had an equal share, no matter what your job was or how long you’d been there. Our best-selling book there was Cultivators Handbook of Marijuana, of which we sold 1.2 million copies, and we did a book of underground comics called Last Gasp. We did a lot of poetry: Ed Dorn’s Gunslinger, Diane Di Prima’s Loba. So as a West Coast publishing company, that was doing pretty damn well. I left there in 1982.

So did TCG lure you away from there?

No, my wife and I wanted to move back [to New York]. There was family here on both sides, we had kids, and we wanted to be near the grandparents, so we decided to come back. I thought I had a job in Boston with Charles River Press, but he gave it to somebody else he had known longer. So all of a sudden I’ve got no job but I’m here, I’m living with my wife’s parents, we have two kids in the house. So I started looking for a job in New York. And the day I got offered this job, I got offered three jobs in the same day. One was with John Wiley & Sons, the textbook publisher on 3rd Avenue; Globe Pequot Press, which is up in Chesterton, Conn.; and TCG, which was the highest-paying job, so I took that one. I started in October of ’82. Peter Zeisler hired me.

What was TCG publishing at that point? There was no American Theatre magazine and no real play publishing program yet, was there?

The publications at that point in time were the newsletter, called Theatre Communications. Lindy Zesch, who was deputy director, had championed the publishing side before I got there. We were bringing out Theatre Profiles every two years, and Jim Leverett, director of literary services, had created Dramatists Sourcebook, as well as a series called New Plays USA, an anthology where we first published Lee Breuer, David Henry Hwang, and Emily Mann. Subcribe Now was in print, and Artsearch was already available. We also wanted to expand, but we didn’t quite know by how much. The first two years of my job were really were taken up with launching the magazine.

We didn’t publish a single-author play until Swimming to Cambodia in 1985. And the book program as we know it really started when we were doing some research about Athol Fugard—we did a story about him in the newsletter, and he was one of the early cover stories in American Theatre magazine—and we realized there was no Fugard in print. Here he is, one of the titans of world theatre, and no books in print? So we republished an anthology of his plays in 1986. There was also no Sondheim in print, so we did Into the Woods. We also did Coming to Terms, a Vietnam anthology, and we did a book on Fugard called Truths the Hands Can Touch by Russ Vandenbroucke.

Another source for our books was the national conference. I didn’t come from a theatre background, so the conferences were where I learned about Suzuki and Boal, who were there. Jo Carson and George C. Wolfe were once on a panel together—can you imagine? The conferences were also how I met August Wilson.

Has the book program always been driven by that impulse, simply to publish the authors you feel deserve to be in print?

Right. And we decided we were going to start doing single volumes of contemporary playwrights. We started looking at authors: Marsha Norman wasn’t in print; we brought her back. Same with Tina Howe and David Henry Hwang. All those people were actually published by New American Library (NAL) in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but their editor left and the company let the program languish so no one was doing it. Grove was doing Pinter, Beckett, but not American playwrights.

Is that because they just didn’t see the financial incentive?

Well, I always thought you could make money selling books. If you do it right, it should be able to pay for itself. At the start, we pretty much paid for the book program every year by our sales, because we weren’t getting any grants for the program then.

I’ve heard you say many times that that the book program is committed to playwrights rather than to individual plays. Has that approach developed over the years or was it there from the start?

That came right away, with the realization that there was no Fugard in print. So if you’re going to publish Fugard, that meant you should be publishing Fugard, not just one play. Craig Lucas might have been our second or third author, Tina Howe, Marsha Norman—all those people we continue to publish, because we felt working with them was important. You were establishing a relationship, and also it gave us a foundation. We didn’t have to say, Oh, what’s the next hot play? Instead, it was, What’s the next play by one of our authors?

The publishing business has changed a lot since you started in it. Can you talk about that?

Well, you have to look at the whole history of trade publishing, and the way it’s been conglomerated—it’s down to about four companies. It used to be 40, and then it was 30, then it was 20. And the requirements for sales became different. Mid-list fiction started to get lost, short story collections were unheard of; literary criticism, are you kidding me? As the publishers consolidated, the level of sales that they required for publication grew higher. Plays and poetry were like [gestures with a flatline]. The only people publishing poetry those days were Athenaeum, New Directions. So there was this whole open market, and at the same time that happened, there was this incredible playwright surge, with all the new playwriting programs and workshops in the ’80s and after. That stuff had to go somewhere. It turned out that as New York publishers were consolidating, that gave room to a blossoming of independent publishing in the ’80s and ’90s, and we were part of that.

Who has been your main competition over the years?

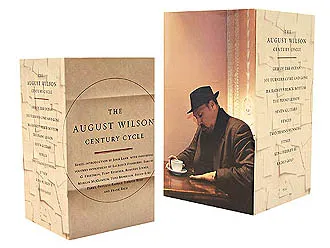

Grove Atlantic was for a while, but not really anymore. Overlook did stuff for a while—they did the Albee collections, which we tried like hell to get, but his agent wouldn’t give it to us. We tried to get August Wilson for a long time, but he was happily published with NAL; Arnold Dolin was his editor. When he left NAL after the first six plays, he took Jitney to Overlook, and then he left Overlook and there was no one to publish his plays anymore.

And that’s when you swooped in.

Our first with him was Gem of the Ocean, then King Hedley II and Radio Golf. And then he started talking to us about how he always wanted to have a hardback set of his work—that was his dream, from his days in the Pittsburgh library when he was a kid. I was in Seattle for the TCG national conference, and we had just brought out Gem of the Ocean, and I kept inviting him out but he was saying, “I’m not feeling that good.” Finally he decided to come, and we went to lunch at one of his greasy spoons. He had flapjacks with eggs over hard in between each flapjack, plus his cigarettes. He was with his oldest daughter, and he was saying, “How soon do you think you can get this out?” That’s when I knew that something wasn’t right. No one had said anything, but I just got this chill over me.

Did he live to see the boxed set, then?

No, he didn’t.

The other big title you’ve had is Angels in America.

One thing I have to say about Tony is that he has as much to do with the success of the book program as anyone, because the fact that we were his publisher made everyone else go, well, if we’re good enough for Tony Kushner… Everyone wanted him: Random House would have given him five arms and three heads to get him in there. And he stayed with us. That gave us a base. From ’93 to ’96, about 40 percent of our sales was Angels in America. On top of that, the same year we published Angels, we went to Consortium Books Sales & Distribution. We used to do our own distribution, because that was my background. I was worried about giving it to someone else, but a good friend of mine who worked with me at Bookpeople became the director of Consortium, so I felt I could trust them with all our books there. So the combination of Tony sticking with us and moving to Consortium was really when our sales started to take off.

Are you generally sanguine about book publishing?

You know, my big regret—about 25 years ago, there was a bookshop in Stony Brook that I was seriously considering leaving here to go and buy. I used to go there when I was a kid. It was a great bookshop. I met with the owner and spent about a week going through all her financial reports; three years prior, Borders had opened about five miles away, and it was sucking half her sales away. I told her, “I can’t do this,” but I was close. That would have been my dream, running a bookshop.

What do you plan to do after you retire?

There’s a Barnes and Noble near me that I might work at part-time. There are some old guys on the register there, and there’s always one old guy at the end of the counter who answers people’s questions. I could be that guy.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org