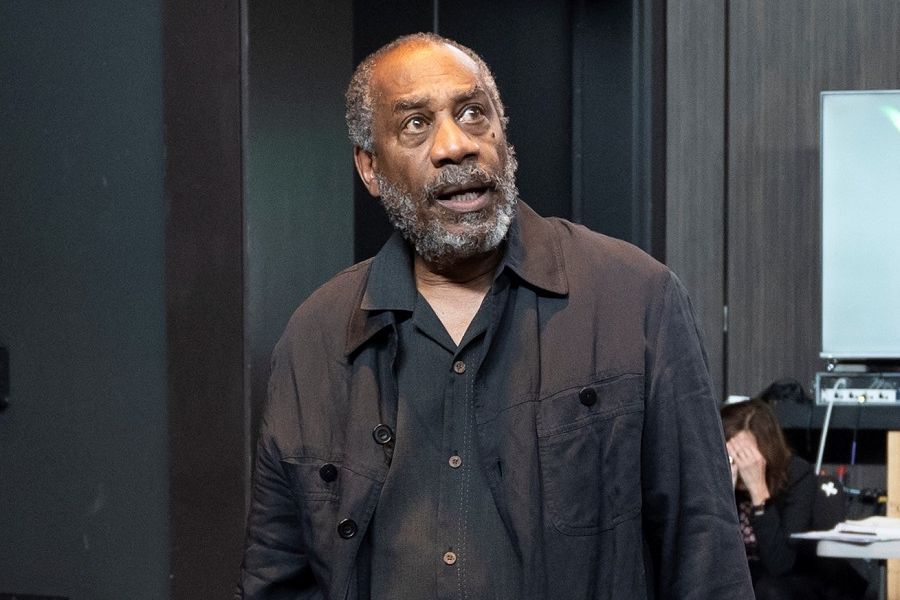

Apart from the white beard he wore in his later years, the great political comic Dick Gregory would not seem to have much in common with Shakespeare’s misguided tyrant King Lear. But that is the unlikely link between Joe Morton’s most recent two stage projects: He played Gregory in the one-man show Turn Me Loose Off-Broadway back in 2016. That play’s director, John Gould Rubin, and the show’s designer, Christopher Barreca, subsequently stayed in touch with Morton, and now the three have cooked up a new production of Shakespeare’s apocalyptic tragedy, which started previews last night at the Wallis in Beverly Hills (it runs through June 5).

Though best known as Olivia Pope’s scheming dad on the TV show Scandal, as well as for roles in such blockbusters as Terminator 2 and Speed, Morton has a long and versatile career onstage and in independent films, including a memorable trio with auteur John Sayles (Brother From Another Planet, City of Hope, Lone Star). I spoke to him a few weeks ago, while Lear was still in rehearsals.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: Why do Lear now? Is this a role you’ve always dreamed of doing?

JOE MORTON: I’ve done a lot of Shakespeare. But I think when it was brought up, I think mostly it became about family. The only reason to do this play is to talk about family—obviously, in this case, two very dysfunctional families, the family of Lear and his daughters and Gloucester and his sons. So what we’ve decided to do is cut all of the other characters except for the Fool and France.

Not even Kent?

No Kent, either. It’s a very streamlined version, and it takes place in the somewhat distant future—we’re talking about maybe 2040, 2045. We are dealing with a planet that is in distress, and is in clear communication between human beings and the atmosphere outside, with the gods. So when we call on the gods, as it might have been when the play was done hundreds of years ago, it’s real, and the curses have some effect, not only on those who are being cursed, but those who are doing the cursing. So it is both a technological world and a mythical world all at the same time.

I want to hear more about that. But first I want to ask about your process in finding your way to Lear. Do you draw on your own family history and psychology, or do you work more with the text and the space?

All of the above. It is drawing on what we understand about families, and it’s a very collaborative process. We’re still at the table at this point, and we are all talking about family involvements and how those work. Including the Fool. In most productions, the Fool is a means for entertainment and humor with very little effect on Lear. In our production, what John and I came up for the Fool is that he very much has influence on Lear. At one point in the play the Fool is gone for two days, so we decided that the Fool has tried to decide where he’s at, what his relationship is not only with the king but with the world in general. He comes back as someone trying to get Lear to understand the mistake he’s made—that splitting the country and banishing Cordelia was not a good idea, it was terribly incorrect and will be terrible for all of us. That’s what his thing is throughout the play. Which makes him a person that has wants, that has needs, that has relationships—makes him an integral part of the play as opposed to comic relief.

It’s a mountain of a role, Lear, even with some lines cut.

The emotions are still huge, because now it’s concentrated on the family, so it’s even bigger in that sense. We’re just looking at what these families are going through; we’re able to concentrate on all that, and nothing else gets in the way. It’s probably more emotional done this way, because there’s nothing to get in the way.

The other thing about a role like Lear is that there are so many iconic takes on it, onstage and on film. Surely you must have seen a number of them, but have you avoided looking at them as you prepare?

I’ve seen a few, and we talk about that all the time. But I believe we are discovering things we haven’t seen in other Lears, specifically the relationship between Lear and the Fool. In many productions, there is very little difference between Regan and Goneril, and we’re discovering that there are huge differences between those two characters—that they don’t approach what they’re attempting to do in the same way, so we’ve discovered the inner conflicts between them and what they want.

You know, I’ve seen lots of Lears, and many of them are wonderful. Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, they’re terrific. But even in the way I want to do the opening—all of them that I’ve seen, the opening is very stern and very formal about what he’s going to do with the country. I am approaching it as a man looking forward to retirement, so the opening is like, “Wow, I’m going to get rid of all this stuff, it’s going to be great. I’m going to live my life. Things are going to be just terrific.” I think his plan was that he was going to mostly be living with Cordelia, and everything was just going to be cheery. That’s how I approach the opening, so it gives me a further distance to fall if, say, Cordelia doesn’t comply with the plan. That’s where the horror begins.

The old saw about Lear is that actors take the role when they’re old enough to look the part but young enough to still pull it off. Obviously you feel you’re in the right place, at age 70. Do you ever think of retiring, as you say Lear does?

Do you know any artist that talks about retiring? I mean, Olivier was really old when he did this part. It’s kind of the opposite of the Scottish play; I think that’s a young man’s play. I see older guys doing it, and I think, yes, I understand why you want to do it, it’s a wonderful role. But it should be for a young man.

So I’ve seen Fran Bennett and Andre De Shields do this role, and I wonder how race plays into your conception of the role, if at all?

What we’ve done is that daughters are a mixed bag: One is Black and one is white. Edgar is white, Edmund is Black. Gloucester is white, and the Fool is being played by someone who identifies as they. So we are dealing with all those contemporary issues at once, and it seems to be working. I suppose in our way we are not doing anything differently than what they did with Hamilton.

You’re bringing your whole self and who are you to the role, but you’re not drawing the lines clearly.

Yeah, it’s not about Black and white.

Can you tell me more about what you’re drawing on for this role?

Well, I have two daughters of my own—there you go. I have that to draw on in terms of my relationships with them. One is, as in this case, much older than the other. As we are playing it in this play, they come from two different marriages. So there’s that to contend with.

The thing about Lear is the madness. We have been talking about what what that means and what that looks like. Edgar has his kind of madness, and Lear has his. And we’ve been telling stories about situations we’ve been in, parents we’ve been around who have gotten older, or who had had problems with their minds beginning sort of slip away and come back again, as we all have with our older parents or relatives.

Also, as I said, the play is being done both technologically and mythically, and part of that effort is to bring the audience into Lear’s mind, so that we are trying to give them a way to experience what that madness is, as opposed to just watching it happen. So when he’s out in the storm, we have the ability, for instance, to project images of the audience on two pillars that are giant video screens, so they are in some ways complicit—I can see them as if I’m seeing them in my own mind. There are all kinds of storms: They can be electrical glitches, they can be storms of language, they can be actual weather, they can also be debris. The audience will be brought into those storms. By the end of the play, we would like them to feel like there is actually a storm outside the theatre. We’re trying to put the audience in a kind of a whirlwind of our imaginations, and to understand what’s happening to these individuals and what it costs them to do the things that they’re doing. Because that in itself is a storm.

In the Hopkins film version, when he meets with Gloucester near the end, there is almost a Beckett feeling to it, like two old tramps waiting for you-know-who.

It’s interesting you say that, because Beckett has come up several times in our conversations about the play. We were talking yesterday about the fact that Edgar’s language changes, not so much toward Beckett, but he goes from almost gibberish to rhyming couplets, like Puck, toward the end. It’s just a marvel that these plays were written hundreds of years ago, and we’re still doing them and still discovering them as if they are new.

You mentioned other Shakespeare you’d done, but the internet is sometimes bad with theatre credits. There was a Two Gentleman of Verona many years ago…

I did Henry IV a couple of summers ago with Tom Hanks.

I read about that, with him as Falstaff—I wish I’d seen that.

And I’ve done The Tempest twice. Once in Stratford—in Connecticut, not on Avon—and the other with Shakespeare & Co., with Tina Packer and her company.

Did you play Prospero?

No, I was Caliban in both of those. Now I’d love to do Prospero. I also did Measure for Measure at the Delacorte many years ago.

Obviously you’ve had a rich career in media, and with that voice, I imagine you’ve cleaned up in voiceover.

You know, it’s funny, everyone talks about my voice, and it pleases me. Mostly what I do are like documentaries and books on tape. I don’t seem to have the skill to do commercials. Every time I meet a commercial agent, they say, “Oh, we’re gonna make a fortune!” And I keep saying, “No, I just don’t have the ability to sell a product.” A couple years ago, I did The Water Dancer, Ta Nehisi-Coates’s first novel, on tape. That’s gorgeous.

How did you catch the acting bug in the first place? Was your voice part of it?

In a certain sense, I guess it was. I went to Hofstra University, enrolled as a psychology major. It was our first day of orientation. They took us around the campus to show us what our first year would be like, blah, blah, blah. They took us into the theatre. They showed us a skit. When the skit was over, I literally could not get up out of my seat. I just sat there staring at the stage. It had nothing to do with the skit; it had nothing to do with anything but the environment in which I was sitting, and the work light up on the stage. I thought to myself: I’d been singing and writing music my whole life. Maybe I could be an actor? I finally got up out of my seat, walked to the registrar’s office and changed my major from psychology to drama.

Wow, that’s a real road to Damascus moment there.

Yeah, I think we all have those moments in our life where that thing happens, where we know we could go one way or the other, and we make whatever choice we make. It’s a very palpable kind of moment for all for most people.

How do you make time to do theatre in the midst of your busy career?

I do mostly television these days, and television has a hiatus. That’s what this is. But for most of my career, if I do something like Speed or one of those bigger films, they have paid for my ability to do a low-budget film, and maybe I do a low-budget film that pays for me to be able to do theatre. It all sort of works out.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org