In the new book The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II (Oxford University Press), hundreds of letters both from and to Hammerstein reflect on every aspect of his life and career. Following are four excerpts from letters written by Hammerstein. The first is to Florenz Ziegfeld, the producer of the original production of Show Boat in 1927. This excerpt is from a letter dated February 16, 1931:

Jerry [Kern] had, what I consider, a wonderful idea in writing a sequel to Show Boat with Kim playing the lead and Robeson playing old Joe’s son, now a successful concert singer. I think this is a germ of a great idea and since Edna Ferber would have to come in on it any way, having created the characters, I should think she might be interested in writing the book herself.

No sequel transpired, but it’s a fascinating notion to contemplate.

This is from a letter to Herman Levin, producer of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and later My Fair Lady. Though it was written by appears that Hammerstein was both an advisor and investor in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. From January 1950:

I saw the show for the second time last week and enjoyed it very much, but there is one blot on it so easy to remove that I don’t understand why you haven’t done something about it. After Channing finishes “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” there is only one possible thing to follow it with—a blackout. If Helen Hayes, Ezio Pinza, and whatever stars you can think of made an entrance following that number, nobody would listen to what they had to say. How then can you expect them to do anything but cough—as they do immediately they see two subplot characters stroll on to play an unimportant scene, and follow it with a reprise. Believe me, Herman, the show falls from one of its highest peaks to one of the lowest valleys in the space of a split second when those two people enter, and a lull is nothing to introduce when you are approaching the end of your second act. I imagine that the original purpose of this reprise was to plug the song, but this is a very expensive plug indeed, and an unfair burden to impose on a musical play. The songs are there only to serve the play, and not vice versa.

If I seem didactic and pompous about this, I am sorry. But it is an offensive thing to me as a showman to see so unnecessary an excrescence on so agreeable a surface. Please forgive the intrusion. It is a gesture of friendship to you all.

The book also contains a wonderful exchange between Hammerstein and Joshua Logan, the original director of South Pacific. In a letter to Hammerstein, Logan goes on for several impassioned pages explaining and defending changes he’s been making while directing replacements to the Broadway cast and directing the company for the national tour. Here is an excerpt from Hammerstein’s much shorter and calmer reply, from May 31, 1950:

Once you start making changes it becomes almost a compulsion to make further changes, to lean over the parapet too far. Shakespeare has lived for many years without changes in the text except for cuts…performances of Shakespeare, however, have been changed a great deal again and again, but the text has been kept sacred. No sane man adds or subtracts words within the lines, although now and then scenes are cut. The most extreme example is Gilbert and Sullivan. Here the text is kept inviolate. Now what of the production, and the direction, and the performance? In the cases where liberties have been taken, mainly in the United States, Gilbert and Sullivan can become very dull. The most successful performances of Gilbert and Sullivan are the D’Oyly Carte presentations and these happen to be the productions that adhere religiously to Gilbert’s original direction and conception. I advance this example not as positive proof that this should be done with all works because I do not believe it should be done with all works, but I do advance it as an indication, a very strong indication, that the longevity of a work depends a great deal on the maintainence [sic] of the original form, and if variations are to be made, they should be made slight and made with great care indeed. Making changes can so easily become an accumulative pastime, not only on the part of one who makes them, but—and this is the main danger—those who follow are likely to be encouraged too much to make further changes. “Oh!,” say they, “you can make changes, can you? Well, now I’ll try my hand.” And after a succession of directors who have not had the sacredness of the original work drummed into them and the inviolability of the original conception, all add their own and put their dirty little fingers in the pie and what have you got—Hollywood!

Rodgers and Hammerstein were both known for checking in on their shows regularly. Here are two excerpts from a long letter from Oscar to John Cornell, the stage manager for The King and I on Broadway. These are notes for Constance Carpenter, who had been Gertrude Lawrence’s understudy as Anna, and who took over the role officially after Lawrence died suddenly in September 1952. The second excerpt refers to Anna’s song, “Hello, Young Lovers.” This letter is dated February 13, 1953:

Please tell Connie that she should be more firm with the Kralahome [the King’s Prime Minister]& on these two speeches that follow each other. When she says: “I expect a bargain to be kept on both sides” she had a sort of pleading gesture last night. She leaned forward as if she didn’t expect it at all, but was asking them to be done. I think she should be straightened out when she says this, and also when she says: “For the time being” there should be a note of defiance and a challenge and the statement of an issue for the audience to watch. There shouldn’t be any quavering in the voice, or any suggestion that she is just whistling in the dark. This is the firm side of Anna, and this is the place to show it…

Please forward my suggestion to Connie that instead of imagining the young lovers being down at about where the horn section is, that it would be better if they were out, if she called out into the night, out into the front. She may answer that she has always been doing this. I don’t know, but if she has I think it’s wrong. I think the lovers ought to be somewhere on the first balcony. They are all the young lovers in the world she is really talking to. The song is bigger than that. She makes it small by singing down to the orchestra pit on her left.

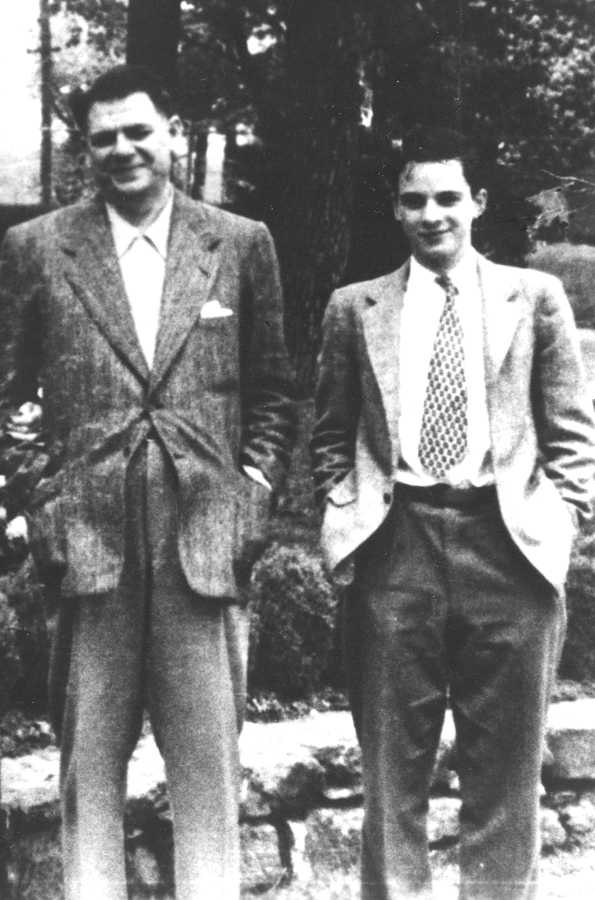

To close, we have a complete letter, this one to a 23-year-old Stephen Sondheim. Hammerstein had been Sondheim’s mentor since he was a teenager, and set him on a course of study to write four musicals—an adaptation of a play he admired, an adaption of a play he liked but felt could be improved, a musical based on a novel or short story/stories (Sondheim chose Mary Poppins, which he abandoned before completing), and an original musical. That musical was titled Climb High. Here we have Hammerstein’s Aug. 6, 1953, response to a draft of the script, which ends with a reference to another idea, a show about the Mizner brothers, to which Sondheim would return 50 years later (in the form of Bounce/Gold/Road Show):

Dear Stevie:

Regarding “Climb High,” not only did we like the original conception, but only a couple of months ago when you restated your theme it sounded good then. At the time I suggested that it was perhaps the prologue that started us off not liking the boy, whereas if you told the story in its proper chronology, without flashbacks, you could get the audience to like him and go with him, as with a son, and be anxious when he went off the track all through the play. Then it would be taking the form of a conventional “race.” I think as I look back on it that you have fallen down badly with your other characters with whom he comes in contact. They all seem shallow wisecracking young people. You know a lot of young people who are nicer than these. I don’t think a play should be filled only with nice people, but it is good to have a variety, and some characters who are foils for others.

Going back to the beginning, however, there is no doubt that a story can be told about a man who instead of learning how to use the tools of his craft, learns only how to put on the proper costume for it, thinking that he is going on a shortcut, and finding in the end that you must always go back and learn how to use those tools. It is as if a caddy on a golf course practices with whatever he can, with whatever clubs he can afford to buy or borrow or steal, whereas another comes out in just the proper kind of slacks or shorts, and well tailored shirt and shiny clubs, and never learns to hit a ball. This is your story and it is perfectly sound. In fact it is the story of “Death of a Salesman.” The salesman, however, had a wife who was very real, long-suffering but really strong and loyal to a touching degree. He had sons who were jerks, but you could trace their jerkism to the salesman himself. He had passed on his phoniness to them. The friend next door was a nice feller and so was his son. The salesman kept deceiving himself and deceiving fewer and fewer other people until finally he couldn’t even deceive himself any more, and so he killed himself. This is a good straight, strong, honest treatment of the same theme.

I would like to talk this over with you at great length (not the salesman, but your play) when you return, or if I go out there—whichever comes first.

The story of the Mizners is of course good material. I agree with your analysis of Wilson. When he cheated he was cheating cheats. His view of life and his behavior may well have been more logical than those of “normal” people. Certainly he was a most entertaining figure. Would your idea be to get any rights from the estates or from Alva Johnson, or to use only factual material and build your own story? The decision whether to make it a biography or a fiction inspired by Mizner is a big one to make. At this moment I don’t know which would be the best.

I have shown your letter to Dorothy and I wouldn’t be surprised if it resulted in a letter to you. She writes to everyone else in the world, why not you?

Love from us both.

Oscar

The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II, compiled and edited by Mark Eden Horowitz, is expected to be released by Oxford University Press on July 6.