On Oct. 3, 1933, the Jüdische Kulturbund, a group of Jewish Berlin artists who made a deal with Goebbels to continue their artistry outside of the racially accepted mainstream, inaugurated their theatre division with a production of Nathan the Wise, an 18th-century fable of religious tolerance among Jews, Christians, and Muslims set during the Crusades. The symbolism of the programming choice would not have been lost on anyone.

The Nazis later banned the play for its message of diversity and accord, but immediately following WWII, dozens of German theatres reopened with new productions of Nathan the Wise. Some who attended the first performance at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin on Sept. 7, 1945, had emotional breakdowns and had to leave the theatre on hearing Nathan’s narrative of how his family was murdered by Crusaders.

Ironically, in 1933 the Kulturbund had to defend the choice of producing a play by a Gentile, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, which implicitly advocated mere tolerance in the face of murderous oppression. Lessing’s Shakespearean tale of a humane Jewish merchant, a visionary Muslim leader, and a Templar Knight who turns his back on war in 12th century Jerusalem has often had doubters. Yet as those of us involved with the Theater J/Folger Theatre production of my new adaptation have discovered, Nathan the Wise, far from being a dated costume drama, is a timely and surprisingly exuberant rebuke of prejudice and intolerance. (The production run through April 10.)

As obscure as Lessing is now, he was revolutionary in his day. A true polymath, he was the first genuine German intellectual. He was an art critic, archaeologist, playwright, pamphleteer, the first dramaturg, and author of a book on the practice as well as a book on semiotics. He was also the co-founder of a short-lived German national theatre.

Though his life spanned only 52 years and he wrote just a handful of plays, his influence on German theatre and literature from the 18th century on was outsized. He led fellow artists away from the strictures of French neoclassicism, dramatizing the concerns of middle- and working-class characters, blending drama and comedy in a strikingly modern way, championing Shakespeare, and penning the first German tragedy of private rather than public feelings. His was a theatre of everyday people.

Lessing could also be a provocateur who found himself at odds with authorities. As liberal Enlightenment thinkers, he and his friend the philosopher Moses Mendlesohn (the model for Nathan) proposed that faith and reason could commingle, and, contrary to Christian precepts, that reason did not have to serve God exclusively. For them there was no single truth, nor should dogma be allowed to constrain freedom of thought. When Lessing was managing a private library, he edited and disseminated texts that questioned the primacy of Christian doctrine. The result was a public dispute with a prominent Lutheran pastor, which led the local government to ban Lessing from publishing religious materials. In response, he decided to move free thinking to his “old pulpit, the stage.”

Lessing died two years before Nathan the Wise was staged. The premiere failed partly due to its four-hour length. But once Schiller later compressed the play, it became a success, with Goethe labeling it a masterpiece and regarding Lessing as one of the great figures of German literature.

In the 20th century Nathan the Wise ran into the opposition of various religious and intellectual figures for purportedly diminishing the specificity of the tribe in favor of a common humanity. Most famously, Hannah Arendt wrote that Lessing could never have argued for an emancipation of Enlightenment-era Jews as Jews. For her, tolerance was understandably a low bar, and Lessing’s “humanity” was an abstraction that implicitly supported the illusory Jewish dream of assimilation in 18th-century Germany.

But the word tolerance is mentioned just once in Nathan the Wise—and in a negative light. Reading the play as a plea for tolerance mistakenly represents Nathan to be compliant and submissive, nullifying the humanism he represents. It also disregards the multi-religious Jerusalem created by the Sultan Salah ad-Din, where all are free to practice their religions.

Later in her career, Arendt changed her mind about the play and Lessing. She quoted Nathan addressing the Templar Knight, who has no interest in being thanked by a Jew for saving his daughter’s life in a fire. But Nathan will not be deterred. He insists: “We must, must be friends.” Arendt recognized that rather than just a personal appeal for acceptance, Nathan’s overture is a social and political act that dignifies difference. “Friendship,” Arendt wrote, is the “central phenomenon in which alone true humanity can prove itself.”

Nathan the Wise is not just the “classic drama of friendship” but arguably the first multicultural play. Though we now tend to overuse the term to denote a plurality of cultures, Lessing’s play urges not just coexistence but mutual respect. In keeping with that ethos, the play presents the first positive portrait of a Muslim leader in Western theatre.

But Nathan the Wise is hardly a philosophical tract. While early translators and adaptors chose to overlook the work’s humor, I heeded an editor who characterized the play as “a sophisticated comedy of ideas” with a serious core of moral thought. Nathan’s most famous speech (cribbed from The Decameron) tells of a magical ring and two copies given to three sons by a father who can’t decide which he loves the most. The sons squabble, then litigate. But the judge they choose to decide the case—surely an inspiration for Brecht’s wily Azdak—rules that they are all too selfish to deserve the ring. The end of the play leans further toward comedy, with a family reunion and a cascade of revealed identities. Even before he began his writing career, Lessing had startled his parents by telling them his goal in life was to become the German Molière.

Like The Merchant of Venice–-its obvious prototype—Nathan the Wise exposes hypocrisies, emphasizes truth-telling, and centers on a Jewish businessman. But as a moral fable, it is far brighter and more hopeful than Merchant. Lessing concludes with Salah ad-Din’s statement that Nathan’s adopted daughter Rachel is the embodiment of the ring speech—the three received religions all in one person. Through the years, critics have referred to Nathan as the “anti-Shylock,” and some of the actors who played one role have also played the other.

Prior to the Theater J/Folger production, there have been just two American productions in recent memory, including an Off-Broadway version in 2017, in an adaptation by Edward Kemp. I have yet to find evidence that Nathan the Wise has ever been seen professionally on the West Coast, and there seems to be only a coterie of American theatremakers who’ve ever heard of it. Despite its affinity with a number of the Bard’s plays, I’m not aware of a single Shakespeare festival in England or America that has produced the play.

How is it that an insightful, always relevant, and pungent “confection” that provides opportunities for diverse casting—one that has been a staple of the German repertoire since Schiller adapted it in 1801—has largely been ignored in this country? Could it be that its title announces a play that might not be of interest to a wide audience, or that producing classics not by Shakespeare has become all too rare in the U.S.? The clotted scholarly translations that were never meant to be staged may have hindered production. But now that multiple adaptations are available, there is every reason for this truly modern classic to find the audience it deserves.

Michael Bloom is a writer-director and the author of Thinking Like a Director and a new version of Nathan the Wise.

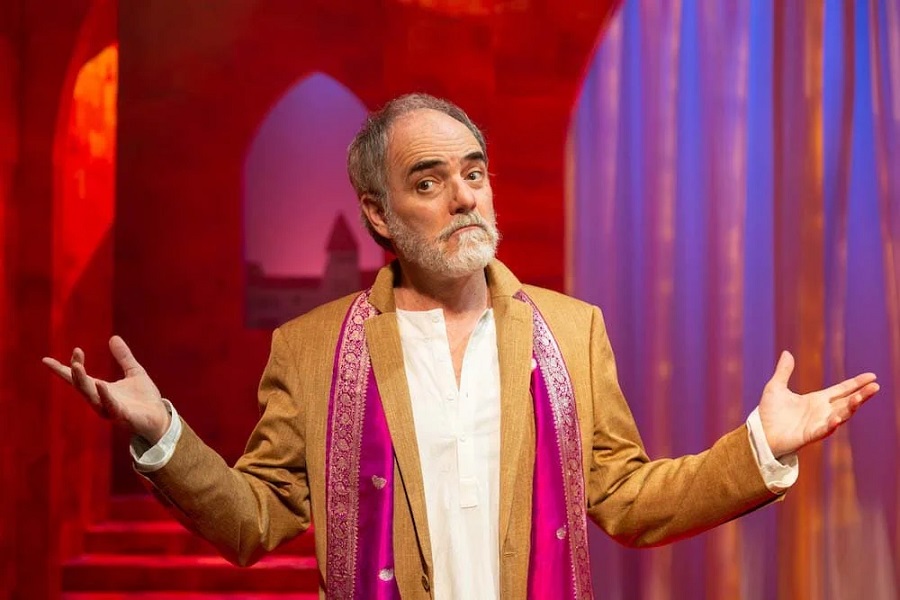

Creative credits for production photos: “Nathan the Wise” by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, adapted by Michael Bloom, directed by Adam Immerwahr, produced by Theater J in association with Folger Theatre, with set design by Paige Hathaway, costume design by Ivania Stack, lighting design by Colin K. Bills, sound design by Sarah O’Halloran, props design by Pamela Weiner, choreographer by Amanda Herring, cultural competency consultant: Adam Ashraf Elsayigh, casting by Jenna Place, NYC casting by Calleri Jensen Davis, production stage manager: Anthony O. Bullock, assistant stage manager: Carrie Edick, assistant stage manager/COVID-19 safety officer: Taylor Kiechlin