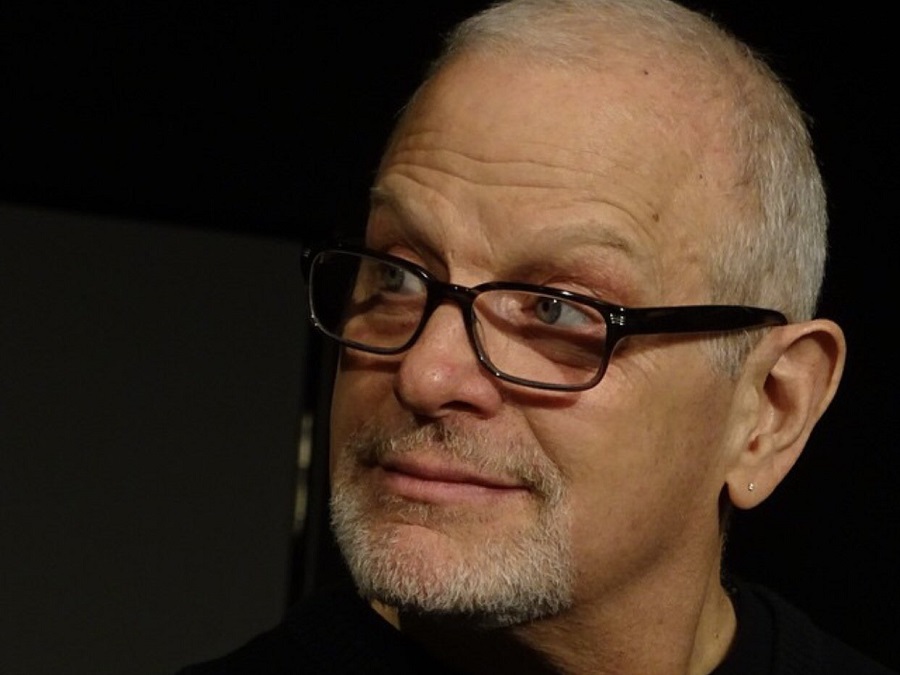

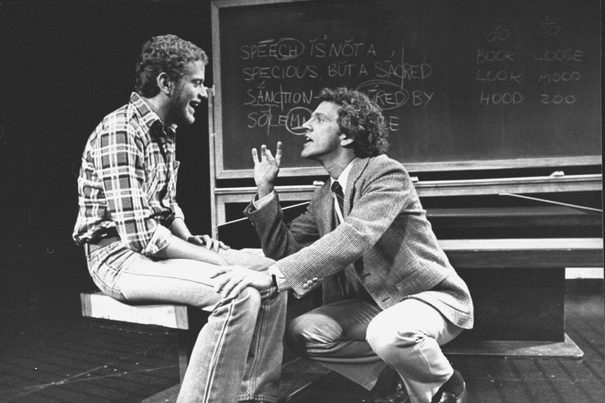

By the time I met and befriended Lewis Merkin, I had already played the radical Deaf student Orin Dennis—the role Lewis originated in the original 1980 Broadway production of Children of a Lesser God—in two different regional productions. My current roommate, James Caverly, understudied my friend John McGinty in the same role on Broadway in 2018. The fraternal bonds of those who have inhabited the role run deep; indeed, there are few male Deaf actors who have not yet stepped into Orin’s shoes. In this industry, staple roles for us are scant, which is why Mark Medoff’s play was so groundbreaking when it first appeared on Broadway in 1980 with Lewis in the seminal role. With his recent passing on March 9th at the far-too-young age of 66, we have lost a true trailblazer and a giant of the Deaf theatre community.

Born in Philadelphia to Deaf parents, Lewis knew from a young age that the theatre would be his calling at a time when roadblocks stood in every direction, especially for Deaf people. Instead of waiting around for opportunities, Lewis knew he had to create them. When he pulled together a production of Peter Shaffer’s Equus for himself to star in at the Pasadena Playhouse, it ended selling out its original run. As fate would have it, Gordon Davidson, founding artistic director of Center Theatre Group and eventual helmer of Children of a Lesser God, was among the lucky few who managed to obtain a ticket, and, based on what he saw, ended up offering Lewis the role that would soon make him famous. Before long, Children was a Broadway smash, running for over two years and winning the Tony for Best Play. Conquering one side of the Atlantic, however, wasn’t enough for Lewis, so he decided to leave the show and take Equus to the Young Vic in London instead.

As one of the very first Deaf actors, if not the first, to become an international star on the mainstream stage, he decided to explore other avenues, including creating new work that represented his intersectional identities as a Deaf, gay, and Jewish man. Language of One, which he co-wrote with Drew Emery, had its New York premiere in 1995 at the Vineyard Theatre, with Lewis as the star. He also toured with the National Theatre of the Deaf for several years.

Even as his health began to decline amid a global pandemic, he continued to have his hands in multiple projects. Most notably, he was involved with the development of A Thousand Faces, a new musical about the great silent screen star Lon Chaney and his Deaf parents. A video of Lewis performing in American Sign Language the song “Like You, Like Me” is featured on the home page of the musical’s website, and he was enthusiastically looking forward to eventually playing the role in a full production.

With New York Deaf Theatre, Lewis was also serving as the head writer for Meat Expectations, a new American Sign Language musical, the development of which will continue in his memory. In a radical new approach, the signed lyrics are being created first before anything else is added, including the music. After Lewis’s passing, a brief video clip of this creation process quickly made the rounds on social media in which Lewis, per usual, ended up leaving the rest of the team in stitches of laughter. I was incredibly fortunate to find in Lewis a great peer, mentor, and source of inspiration as a fellow multifaceted Deaf theatre artist. The fact that we shared the same birthday (Dec. 18) only deepened the connection.

After our initial meeting, we quickly became steadfast theatre companions. Before the pandemic shut the world down, nary a month went by that we didn’t see at least a few shows together. Since we both lived in Queens, we would ride the same train back home and rehash the minutiae of every show and nuances of every performance.

The very last thing the two of us attended together was Jagged Little Pill on March 10, 2020, a mere two days before Broadway shut down. Less than two weeks later, unable to stay away from the stage, Deaf Broadway was inadvertently founded in my living room. A collective of Deaf actors, we provided American Sign Language access to major works of the American stage via a virtual interface. Lewis memorably played the role of Larry in our version of Stephen Sondheim’s Company, and while the two-dimensional quality of the Zoom platform was naturally unable to contain his infectious energy, I will never forget the raw emotion in his teary eyes as he signed “Sorry-Grateful,” nor the twinkle of exquisite, mischievous joy as he danced drunkenly in the second act.

One of the very last times I saw Lewis in person was last summer, at the open-captioned performance of the Public’s Merry Wives at the Delacorte, after which we found a small café nearby and caught up with each other at an outdoor table under the stars. It was a quintessential New York evening that will stay with me always. That was the night he told me about the cancer that would soon rob us of his light, but he was still hopeful, and, as was typical of Lewis, quickly brushed the topic aside in favor of talking about our work.

Indeed, our friendship was kindled by the theatre, sustained by the theatre, and will live on through the theatre. Now Lewis has joined those stars that shone down on us that night last summer, helping all those who follow in his footsteps navigate the perilous journey to the stage and guiding the way for the generations of Deaf performers to come.

Garrett Zuercher, a veteran stage and screen performer, is also one of the founders of Deaf Broadway, a collective of Deaf actors who make theatrical productions visually accessible in American Sign Language.