Out in the hallway of the Su Teatro Culture and Performing Arts Center, a call-and-response chant between a union organizer and strikers is building. “Se Puede.” “Si se puede!” “Se Puede.” “Si se puede.” “Se Puede.” “Si se puede”! “Se Puede.” “Si se puede!” Soon those strikers are marching into Su Teatro’s 300-plus-seat mainstage theatre, placards aloft, shouting, “Huelga! Huelga! Huelga! Huelga!” “So begins Su Teatro’s Papi, Me and César Chávez.

Written and directed by Anthony J. Garcia (he/him), the young-adult-appropriate musical is narrated by 10-year-old Gloria, whose father, a migrant laborer, tries to resist the call of the soft-spoken firebrand who keeps nudging him to join the United Farm Workers Union. It’s 1966, the year Chávez and supporters marched 250 miles, from Delano, Calif., to Sacramento, to protest exploitative wages and dangerous working conditions.

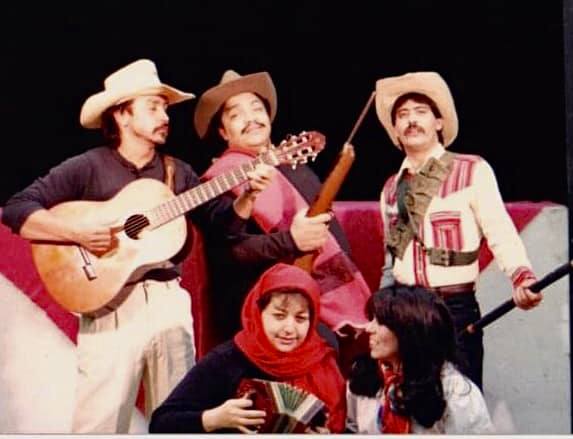

A musical celebrating Chávez and exploring his meaning for a young Chicana is especially apt at one of the oldest Chicano theatres in the country. Founded in the era when the teatro campesino tradition was ascendant, Su Teatro is now celebrating its 50th year honoring that tradition. Indeed, the cultural wing of the UFW and Chicano activists saw performance as integral in connecting laborers and deepening community.

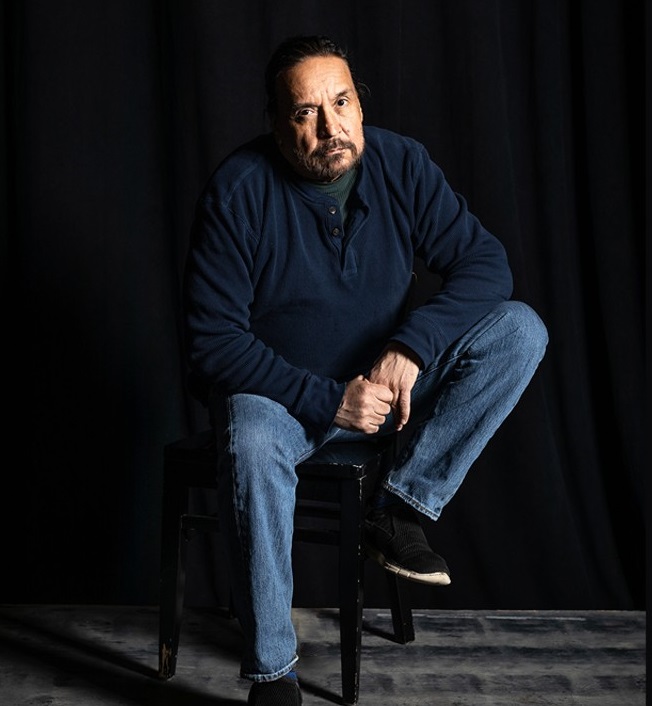

During intermission, Garcia, Su Teatro’s executive artistic director, kneels in the aisle to say hello. It’s opening night, and while the onstage band has been ace and the ensemble as a whole has suffused the theatre with the energy of a proud resistance movement, the young college student portraying Gloria (Vianney Aguilar) hasn’t yet calmed the nervous quaver in her voice. “They’re a little green,” Garcia tells me, without apology and with his customary easy candor.

That Garcia says this to a journalist, pen and notebook at the ready, might strike some as odd. Instead, it’s a deft reminder of what he values even more than upbeat reviews: process. He loves the kind of work that brings people into a space, into community, into their own and their families’ stories. It’s not an anti-aesthetic argument. The work is the aesthetic.

“A lot of times, people don’t understand that the community engagement, the authenticity of what people are doing onstage, is really a core part of the aesthetic of the organization, of the work that we do,” Garcia says in a later interview in the center’s roomy black box theatre. He believes his actors understand it, and, he thinks, the young star of Papi does too, in her bones. “There’s an aesthetic there that I don’t know I can duplicate with somebody just going out there and going, ‘This is just a role.’ This is not just a role [for Aguilar]. This is a step in what she wants to see in herself.”

Some of Su Teatro’s best productions remain indelible in my memory. Northside, by Colorado’s poet Laureate Bobby LeFebre, about the rampant gentrification of a Denver neighborhood, and Garcia’s documentary play War of the Flowers, about the female-led fight to unionize the Kitayama carnation factory in Brighton, Colo., in the 1960s, come easily to mind. Su Teatro’s collaboration with Denver’s Black theatre company, the Source, for a moving production of Gospel at Colonus, also remains a standout. But the ones with rougher edges are often just as meaningful.

“What I have learned in recent years about Su Teatro and Tony’s vision is how that place is my community—it’s like home,” says Chrissy Deal (she/her), a director at the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation, Denver’s premiere arts and culture funder. “It’s like a home for storytelling. I don’t go to every performance, but when I do go, when I invite friends, or go with my family, or take my kids, and we learn together. We feel comfortable there. We feel welcomed there. And that’s what I have come to really appreciate, and realize that it doesn’t happen anywhere else in the city.”

The milestone celebration began in earnest with a reprise of El Corrido del Barrio, a work about the imminent domain removal of as many as 300 Mexican families out of their neighborhood west of Denver’s downtown to build what became the Auraria Campus, a complex of three colleges. The commemoration of the theatre’s anniversary continues through August 2023. Why nearly two years? Because one year cannot accommodate all the work Su Teatro plans to revisit, shows like Corrido and Papi, Me and César Chávez.

Garcia says he hasn’t seen Papi in the 17 years since it debuted. “There was a whole different intent when we started it,” he says. He remembers talking to a classroom of kids, who, when he asked if they knew who César Chávez was, thought he meant Julio César Chávez, the boxer. He grins. “They all knew who he was. So, it’s like, okay, we should do something so they can learn who he is. And it kind of morphed into this.”

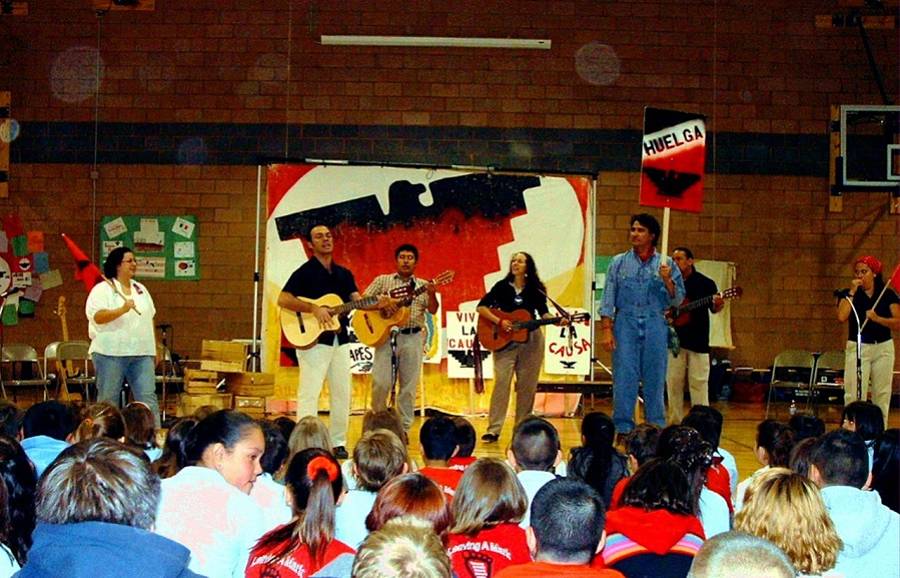

Though Papi, Me and César Chávez hadn’t received a mainstage production in years, it hasn’t been sitting in mothballs. In various guises, the show has been a staple of the organization’s outreach and education program for 17 years, traveling around the Denver area and the state. Mica Garcia de Benavidez (she/her), who heads the education program, recalls a particularly poignant stop in the tiny rural town of Gilcrest, where Hispanics comprise 52 percent of the population. “We did it in the evening there for the whole community, not just for the high school,” said Benavidez. “You had kids who understood it on a very different level, understood what their family has gone through.”

Benavidez, Garcia’s daughter, attended her first Su Teatro show when she was a few days old. Now she is managing director and director of the organization’s Cultural Arts Education Institute. It may speak to a lovely irony, or just art mirroring life, that while rehearsing this recent iteration of Papi, Garcia was struck by the precedence of the Gloria-Papi dynamic over the original educational inspiration. He says he noticed “how much it says about the relationship between the daughter and the father, and about the sacrifice of the previous generation, and really not very much about César Chávez.”

Su Teatro owns the building on Santa Fe Drive, emblazoned with a mural of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent of ancient Mesoamerica (a project of nearby Metro State University students and artist Carlos Fresquez). That’s a good thing, because Denver continues to be in the throes of a real estate land grab. If LeFebre and Garcia decided to mount a sequel to Northside, it might feature a long-established Chicano theatre trying to care for and feed a community amid a dramatically changing corridor, where multi-storied apartment buildings are crowding out art galleries and other small businesses, and modest homes just a block off the corridor are being devoured by developers.

“We owe less than $100,000 on the building, and we’re going to get it paid off this year,” Garcia says proudly. The Su Teatro board has started to take issues around gentrification seriously. “So many of our people, our communities are losing their spaces because they can’t hope they can’t hold on to it. We’re not going to be in this position, but we have to start looking at what we do with the space that we have. Can we expand our footprint? What can we do with that space? The cultural arts education program is actually bigger than our theatre program. It generates more revenue, more activity. How does that expand?”

He knows these will remain vital questions—sure to be tackled during Su Teatro’s next 50 years.

Lisa Kennedy lives in Denver. She writes on film, theatre, and culture for a number of publications and teaches nonfiction writing at Lighthouse Writers Workshop.