This is one in a series of stories marking the two-year anniversary of the COVID-19 shutdown. The full package is here.

The Chinese Lady is back in New York. This time, on her own terms. When 14-year-old Afong Moy was brought from Guangzhou to New York by traders in 1834, she did not have a choice. When they branded her the first Chinese woman to set foot in America and made her live as a traveling museum exhibit, she had no control over how she or her culture were represented to the American public: her bound feet, her attire, and her use of chopsticks, were all sources of exoticism and spectacle. Then, in 1850, for one last trick when the allure had faded, they made her disappear. Afong Moy was practically erased from American history.

In The Chinese Lady Lloyd Suh has given Afong a voice and a space to tell her story, albeit 188 years late.

“I am back in New York. Or I should say, we are back in New York. The three of us: Me, Atung, and of course, The Room.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

The Chinese Lady is currently playing at the Public Theater (Feb. 23-April 10) on Lafayette Street, in the same city where the real Afong Moy made her first reported appearance. Its rumination on Asian representation and the white gaze comes amid an escalation of anti-Asian hate crimes. It has another kind of timeliness too: As the most-produced play of the U.S. 2021-22 season, it is helping theatres find their way back out of the lockdown necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Suh (he/him) recalls being “haunted” by the story of Afong Moy while doing research for another play in 2015. “I wasn’t terribly self-aware of the ways in which she was haunting me at the time,” Suh said. “But as I began to think about her and research more, and then eventually began to start exploratory writing, the layers of that haunting just kind of grew until I knew that I had to do something with it. It became a play once I realized that I couldn’t wrestle with it just on my own in my head in some theoretical way. That I needed to get in the room with peers and wrestle with this together.”

The opportunity to develop these ideas came at Magic Theatre in San Francisco, where Suh was attending a benefit and artistic director Loretta Greco offered to put him in a room with some people where he could experiment with new material. Then, as recipient of the 2017 Roe Green Award, Suh began a week-long residency at Cleveland Play House, which allowed him to produce a first draft of The Chinese Lady without a definitive ending. From there he went home to New York and participated in a series of one-day readings with friends at New Dramatists, where he’s a resident playwright. This is when his show’s ending finally clicked.

“The moment when I was able to tie it all together was the moment when I realized we’re these actors: the idea that we’re always ourselves, in the theatre, even at the top, when we’re inviting an audience to imagine themselves as a 19th-century audience—we’re always, always ourselves. The actors are always the actors, the audience is always themselves. And we’re conjuring her imperfectly because she is unknowable.”

In this way, Suh speaks to the consequences of a whitewashed history. Many of the reasons for Afong Moy’s erasure are still with us today.

“The first the first the first.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

The full world premiere of The Chinese Lady—a commissioned co-production with Ma-Yi Theater Company—took place at Barrington Stage Company’s St. Germain Stage in Massachusetts, where it ran July 20-Aug. 11, 2018). This is the same production, under Ralph Peña (he/him), that has made its way to the Public, after first having a brief New York run at the Samuel Beckett Theatre at Theatre Row (Nov. 7-18, 2018) and a staging last fall at Long Wharf Theatre. Peña, the artistic director of Ma-Yi, has long been a close collaborator of Suh, who said they “have a certain shorthand, a certain shared vocabulary not just around the work, but I also feel like we have similar ideas of what we want our theatre to do, and how we wanted to challenge and or advance a conversation around what it is to be an Asian American performing artist.”

For actor Shannon Tyo (she/her), who originated the role of Afong Moy in 2018, this play was kismet. “It actually came around at a really interesting time in my life,” Tyo said. “At the time I received the script, I was in the midst of taking this really deep dive into Asian American history.” As an adopted person, Tyo did not have Asian American culture passed down at home, and Tyo was further fascinated by the wealth of AAPI experiences that had not been discussed in school. She happened to be looking for a way to share these stories when The Chinese Lady fell into her lap.

“Learning that stuff made me feel more grounded and more centered,” Tyo said. “It was like an answer to the very microaggressive comment that Asian Americans often get, which is like, ‘Where are you really from?’ And it felt like an answer to that, like, ‘Oh, I’m from here.’ You don’t have to look for another justification. Asian Americans have a history in America, even though it hasn’t been focused on.”

While Afong Moy was toured from city to city in a show of Orientalist curiosity, the journey of The Chinese Lady to several U.S. stages has encouraged regional theatres to have vital conversations about AAPI inclusion and representation.

“Barrington is in a predominantly white community,” said Peña. “I had never before been in that kind of environment. It was very interesting for me to sort of see how they responded to the story. There were a lot of talkbacks, and it was fascinating to me how people saw Afong Moy. It’s different from how New York audiences received her.”

As an example, Peña noted that while audiences at Barrington focused on Afong Moy’s bound feet as a sign of exotic otherness, even eroticism, New York audiences were more inclined to see the person behind Afong Moy’s sideshow persona. Peña added that among audiences unfamiliar with the history, “I think there was probably less awareness of the reversed gaze that the play was hoping to do. It was received differently. And I think that that’s a mark of a good play, that you can bring different experiences to it.”

In fact, this malleability is intentional. Suh said he hopes that each production of The Chinese Lady can be a reflection of its own time and place. “When I have an opportunity to talk to the different creative teams in advance of different big decisions being made,” said Suh, “I try to urge as much as possible to the personalization, and the localization, that they identify particular goals for that production, the feel of that city, of that moment, of those artists, of the community conversation that’s happening in that city…it’s going to mean something different everywhere.”

“The place I began was a place of endless possibility and earnest good hope. It was a place of aspiration and empathy, where we could all look upon something we’ve never seen before and recognize that the world is so much more vast and varied than we could ever have imagined.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

The Chinese Lady next made its way to the Milwaukee Repertory Theater in Wisconsin (Feb. 13-March 24, 2019), where artistic director Mark Clements (he/him) was captivated by Afong Moy’s story. “It was just a very subtle play,” said Clements. “I think it’s like a small, subtle play, which has a huge amount to say in a very nuanced and economical way. And I think I was very drawn to that kind of writing.”

He wasn’t the only one; his audiences responded very well, he recalled.

“One of the things we felt was that the Afong Moy role was just such a tour de force for that actor to play,” he said (Lisa Helmi Johanson took the role in Milwaukee). “I think about what the play had to say about cultural appropriation or misappropriation, and that was just such a really original, exciting role for someone to create.”

The pandemic shutdown would have an impact on subsequent productions of The Chinese Lady, but it also had material impact on its playwright’s fortunes vis a vis Milwaukee Rep. Like many theatres, they shelved many production plans and pivoted to other priorities—including, Clements said, their new-play development program.

“It was fortuitous in some ways, because we did actually end up being able to develop a number of our new plays in a more extensive way, in a more comfortable timeline for everybody,” Clements said. “I am hoping that will be seen in the work that we eventually produce.”

One of those new plays in development is Suh’s The Heart Sellers, now slated for Feb. 2023, and commissioned as a direct result of their collaboration on The Chinese Lady.

“The act of writing plays is kind of a future tense activity,” said Suh. “Because the writing of it presupposes that one day, you’ll get in a room with others, for an audience. And that day is nebulous, and potentially non-existent, and far off into the future in some speculative way. During the pandemic, that was compounded, obviously. And so the aspiration wasn’t just about: Maybe one day I’ll be able to get in a room and work on this. The aspiration was about: Maybe one day the world would be better. Maybe one day this industry will come back…I allowed myself to think about it as something that one day, in a different world, might have a resonance.”

There was also a co-production of The Chinese Lady performed in Los Angeles in Sept. 2019 at the Greenway Court Theatre by Artists at Play and the Greenway Arts Alliance.

“I have been waiting for you for so long.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

The Chinese Lady next headed for Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, Conn., where a version of the original Ma-Yi production was scheduled to premiere in the company’s 204-seat proscenium black box theatre on March 18, 2020.

“There was a moment where I went into the space,” recalled Long Wharf artistic director Jacob Padrón (he/him), “and I was really taken aback by just the beauty of all the elements, the set looked fantastic, the costumes looked beautiful, the props, the lighting, just everything. Any time you go into that tech process, you’re always looking for that alchemy, you know, for all the elements to come together right before the audience comes and participates in the process.”

But while inside the theatre everything was coming together, outside the world was falling apart. On March 12, the first day of tech rehearsal, The Chinese Lady had to close before it even opened.

“So then, like everyone else, we got that moment of having to shut down and hoping that it was going to be just a pause,” said Padrón. “Then the pause turned into days, turned into weeks, turned into months. Early on we made the decision that we were going to save the sets and the costumes. We didn’t know when we were going to be able to get back to it.”

Indeed, said Long Wharf’s director of production, Nicole Bouclier (she/her), they considered many options for the production, including filming it. “I had done a round of budgeting for that. Filming is so tricky when you don’t have the infrastructure. It’s such a different beast than producing theatre.”

They didn’t end up filming the show, but one expense they did meet: They paid the entire cast and crew for the cancelled run.

“The way that you spend your money reflects the values of your institutions,” said Padrón. “Show me your budget, and I’ll show you your values, as the saying goes. All of the humans that go into creating the community to tell a story—folks need to be paid for that work, for that labor, that physical labor and that emotional labor. So even though we weren’t able to bring in revenue from ticket sales, it felt really important to acknowledge the work that had happened by paying everybody for the work that would have happened had we not been shut down by a global pandemic.”

Not including pay for full-time staff, Long Wharf’s original production of The Chinese Lady had a budget of $180,000. The pandemic would force Long Wharf to make significant cuts across the board. “We downsized our staff to half,” said Bouclier. “We were over 55. And I think we cut it down to a lean 22.” From the overhead costs of renting and maintaining a building, to the installation of air purifiers in all shared theatre spaces, as well as investing in masks and twice-weekly PCR testing kits, the pandemic was an expensive time for the theatre.

All the same, the team at Long Wharf saw the pandemic as an opportunity for innovation. They were able to continue the LAB, an experimental artist-led hour of showcased material. They also produced a film of their production A Little Bit of Death and staged an outdoor summer musical presentation of Passing Strange. They even held a virtual “State of the Union: Artistic Congress” where playwright/activists Luis Alfaro and Dominique Morisseau discussed the political landscape and offered love letters to the future of American theatre. In his love letter, Alfaro wrote, “A great pause has become the great possibility.”

These words inspired Padrón to take Long Wharf Theatre in a new direction, he said: In February, Long Wharf announced plans to leave behind its headquarters altogether and adopt an itinerant model.

“This is an opportunity to use this pause to imagine the possibilities,” said Padrón. “And I think that there is an opportunity to get back to, I would like for us to usher in a sustainable model that allows the company to be financially healthy.”

“I speak for myself, and my voice is beautiful.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

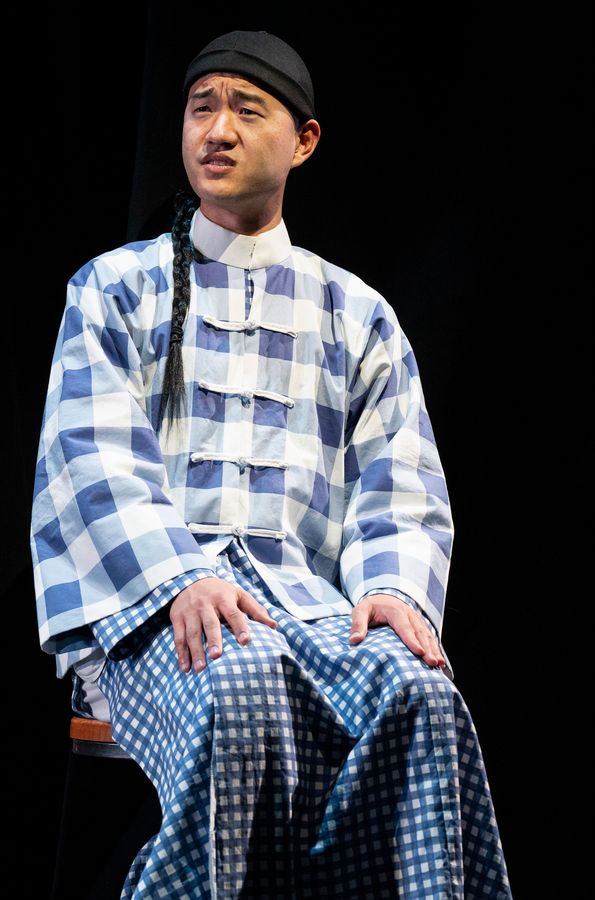

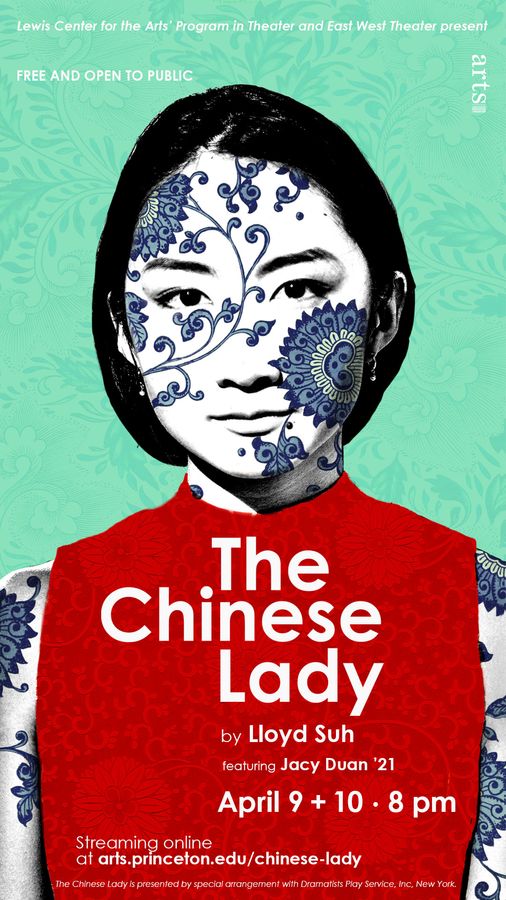

In April of 2021, The Chinese Lady made a detour to New Jersey, to Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts, where senior Jacy Duan (she/her) was preparing to perform in an empty theatre. Duan had submitted a proposal for The Chinese Lady to the theatre department during her junior year in January of 2020. She chose the play for her senior thesis.

“I wanted to do something that had a strong Asian female character,” Duan said. “I realized that I had never actually played a role in any show in which the character was written to be Asian. I’d done so much theatre at that point, but then suddenly realized that I had never done that before. Which was very weird. And so this was really important to me. I really wanted to do something that spoke to my Chinese American background.” When Duan first read the play, she cried.

The theatre department approved her proposal and planned to stage a small production in their black box space in January 2021, with a full season of musicals and larger productions in their main theatre. Then the pandemic happened, and one by one every live production was canceled.

Except The Chinese Lady. With only two characters, a single set, and a five-person production team, the play was deemed isolation-friendly. Besides Duan, the production consisted of her co-star junior Jonathan Som, who played Atung, director and Princeton alumnus Richard Peng, scenic and sound designer senior Minjae Kim, costume designer and stage manager junior Megan Pan, and lighting designer sophomore Angelica Qin.

“This show actually ended up being the tentpole show of our season,” said Duan. “It was just originally supposed to be this small, intimate black-box exploration, and ended up being the show they spent the most money on that year.”

At first, Duan and her production team did not know if they would be allowed to perform when the university’s theatres closed. They rehearsed over Zoom without blocking, got tested three times a week, and waited. After a lengthy appeals process, they were granted permission to film the production in the Wallace Theater in March. They had three weeks to rehearse in the space before filming. The catch? No one else could be in the theatre. Even the cameraman had to press record and leave. This meant everyone was multitasking. Duan had to do hair, makeup, and intricate costume changes by herself. She even had to do some of the sewing, as no one was allowed to touch the costumes.

Despite the complicated filming process, the virtual production had a special benefit. “Such a unique thing that came out of this was, because it was filmed and put up virtually, me and the director asked if we could have Chinese subtitles,” said Duan. “My parents are Chinese immigrants and they speak English, but not very well. They do not understand theatre. And so they’ve been seeing shows I’ve been in my entire life, but they’ve never understood what was going on or had a very basic understanding.” Subtitles meant that The Chinese Lady “was the first time my parents were able to fully understand a show I was in…That’s something that definitely would not have happened if we were just doing the show live.”

Duan said that her parents loved the play and were very proud. (Of the production’s 300 streams, 6 were from Duan’s father watching the production on repeat.) They were even able to share the film with her grandparents and other relatives in China.

The Princeton production happened to stream April 9-10, 2021, just three weeks after shootings in Atlanta that killed eight people, six of whom were Asian women. People kept remarking on the timeliness of Duan’s production, which was of course coincidental.

“It just goes to show that this is something that has been going on,” Duan said of this unplanned resonance. “This is something Asian women have been experiencing and enduring since Afong Moy. It’s not a singular experience; it’s something that’s been happening and will be happening.” As Duan put it, The Chinese Lady “really epitomizes all of the issues that we are going through. Asian women aren’t seen as people—we’re more objects of fetishization than we are people. Even now, when we see stories of Asian hate crimes, the majority of the time they’re happening to elderly Asian women. And that’s a huge issue, that Asian women aren’t seen as people who can be strong, who can fight back, who are human beings.”

Suh also noted that the harmful rhetoric spread about the pandemic’s origins in Wuhan, and the rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans, have influenced responses to The Chinese Lady.

“I definitely feel like the play lands differently, not just for the audience, but for the performers,” said Suh. “Some things might have more of an edge to them, some things might have more vulnerability. I feel like what’s happened over the past couple of years is that this country is now in a very self-aware reckoning about what it is to be an American, what it is to live in a country that has the kind of history that it has, and how the color and the origin of our bodies, influences the way we navigate that history. I think that reckoning has a big impact on the way that performers speak those words, but also the way audiences receive them.”

Added Daniel K. Isaac (he/him), who originated the role of Atung, Afong Moy’s onstage translator, and is now in the Ma-Yi production at the Public, “When we did this play in 2018, it might have been a struggle at times for audiences to believe that someone who is Asian-bodied in America could have struggles or incidents of hate crimes against them. And now we wonder if that burden of labor is easier, or at least more widely accepted, given the statistics that have come to light. It certainly does affect our performance.”

A sobering reminder of the stakes involved came on The Chinese Lady’s first preview at the Public, which included a celebratory performance of Yip’s Dragon Style Kung Fu and Lion Dance, a troupe based in New York’s Chinatown. One of Yip’s performers arrived at the theatre with his eye bruised and glasses broken, as he had been brutally attacked on the way in. Though he could not see well as a result of his injuries and was unable to perform his original role, he insisted on playing one of the instruments so that the performance could continue.

“They told us right before we had to go onstage,” recalled Isaac. “So we just compartmentalized that as fast as we could.”

As Suh put it, this frightening real-life backdrop gives the play “a present-tense urgency. That this is a conversation that a lot of my peers want to be having, they want to be having with each other, and they want to be having with audiences within their communities.”

“But before we can move on to a new set of traditions, we must live in a slow dismantling of the old ways.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

In October of 2021, The Chinese Lady finally opened at Long Wharf (Oct. 12-31, 2021). Jacob Padrón felt it was the right decision to pick up where they left off.

“The more that we started to talk about how we would re-emerge as a theatre company,” said Padrón, “and what story we wanted to actually come back with, the play felt more timely than ever. The other thing that just felt right was that we could really frame this as an intermission—that the play that we stopped with is the play that we’re going to return with. It also felt really, really important to honor the work that had already been put into place by the actors, by the director, by the designers, by the stage management crew.”

This time around, The Chinese Lady premiered on the theatre’s main Claire Tow Stage. “The HVAC system in our smaller space just wasn’t up to snuff for the audience,” explained Bouclier. This meant that the proscenium staging would have to be redesigned to accommodate a three-quarter thrust configuration.

With those adjustments, the show was able to go on as planned. For many, including Suh, it was their first time back in a theatre.

“I mean, just on a metaphorical level, it felt like the thing that was put on hold was coming back,” said Suh. “And just that felt momentous, it felt like there was a life thing happening there. It just felt like reemerging. There was hope. I remember, I was in the lobby and they gave me a ticket. And I was like, ‘What do I do?’ I forgot how to be in a theatre. Recognizing that I had forgotten how to be in a theatre made it just feel so special. Somebody asked me recently, ‘What do you think is the future of theatre?’ I don’t know what the future of the world is, or what the future of anything is. But the only way I could really answer it was to say that it felt like the impulse to gather, the impulse to share space and to be with people and tell stories in person is growing stronger rather than weaker.”

Meanwhile, though, Ma-Yi Theatre Company was not idly waiting for in-person theatre to return. The idea of Ma-Yi Studios, Peña said, was to “employ artists during the pandemic, because I knew not everyone qualified for unemployment, not everyone qualified for assistance from the government, so they needed to make paychecks. And that’s how we got media out to them, by creating digital work.”

“It’s created a different kind of work,” said Peña of the two years of pandemic lockdown, which shut down three planned Ma-Yi productions. “As soon as we shuttered those three shows, I began talking to funders about moving to an all-digital format. This was in March 2020. By April, we had a studio up and we decided to do digital work. And that’s sort of created a whole new creative vocabulary for us that we had never done before.”

The company purchased $200,000 worth of digital equipment and converted their midtown rehearsal studio into a recording studio. They hired a consultant to teach them the basics of streaming and sent remote kits with cameras, computers, lighting, and sound equipment to the actors’ homes so they could set up their own studios.

The result, Peña said, was work that reached close to 3 million people worldwide, including in places lke India, China, Singapore, and Japan. “They were all fascinated by what ‘Asian American’ means, basically, or that there’s such a thing as Asian American theatre,” he mused. It wasn’t a revenue stream per se (“We stream for free, we only ask for donations”), but it certainly raised awareness. “We didn’t raise a lot of money, but it’s fascinating—like, a million viewers from India? That’s insane, but that’s what happened for us. And I don’t want to lose those audiences. So right now we’re trying to figure out how to do both.”

“This Room was built with a hope that it might serve as a platform for understanding, for learning, for sharing.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

The next stop on the The Chinese Lady itinerary was Artists Repertory Theatre in Portland, Ore. (Oct. 19-Nov. 14, 2021). Director Lava Alapai said she felt a certain kinship with Afong Moy.

“I read it, and I was immediately drawn to Afong’s story,” said Alapai. “I’m an immigrant myself; I came from Okinawa, Japan. And coming to America was strange. I mean, my memories of home, driving away from it for the last time—that memory never goes away, leaving your home for the last time…So her story is one that I related to in the way that you come to America, and then you have expectations put upon you or expectations that are set in motion, and as a young person, you don’t know what or how to do it, or what your place in the world may be. And her story was one that I had never heard of.”

The cast and crew wanted to pay respects to the very real history that they were bringing to life onstage. “Because this was based on a real person,” Alapai said, “we put a little offering to Afong and Atung under the set, for them to join us. And then we sent that spirit along to the next cast” (at Philadelphia’s Interact Theatre).

Alapai noted the particular history of Chinese Americans in Oregon. In fact, the Armory where the show was performed was initially constructed as a National Guard outpost to quell anti-Asian riots in the late 19th-century, after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act and a rising white backlash against Asian immigrant workers. It was important, Alapai said, to “acknowledge that we were putting this play on in a place of exclusion, where we were now removing that exclusion and including this story, and the people around this neighborhood, and around this armory. Now the Armory is a place of inclusion.”

“Like cracks in a bell or a story of when it first rang, we can only simulate the past, not in pursuit of the literal truth but some other less tangible truth about ourselves and the nature of truth itself.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

Although The Chinese Lady is a new play, that doesn’t mean it hasn’t already been subjected to radical reinterpretiation: At InterAct Theatre Company in Philadelphia (where it ran Oct 29-Nov. 21, 2021), for instance, the creative team made the bold choice to present the events of the play in reverse chronological order.

“When I first read it,” said director Justin Jain (he/him), “I couldn’t shake this nagging tug to say, we have to center this here and now—it has to be in 2021. This is in the wake of the cultural reckoning that has happened over the pandemic, and the anti-Asian fears stoked by COVID-19 as well as the Atlanta shootings, and things that were happening locally in Philadelphia. There’s a lot of tension with the Asian community and in some of the high schools here. I couldn’t help but feel like: I can’t just enter this piece in the 1830s and play nice with our audience until the end, when it sort of zooms back into the present. For me, it was really important to stay present and to stay grounded in this moment.”

So InterAct’s production began in the present day, with the actors appearing as themselves. Then, as the story moved back in time to 1834, audiences witnessed the performers transform into Afong Moy and Atung.

Another of InterAct’s creative decisions was to bring Philly-based Chinese American musician Mel Hsu onstage to explore the concept of colonized sounds and music from the homeland.

“In the true story of Afong Moy, she didn’t come to America by herself,” said Jain. “She came with an unnamed female attendant. I kind of wanted to honor that spirit as well. So on our stage, we have Atung, Afong Moy, and this unnamed female servant, who also served as a kind of musical bridge between the audience and the play.”

Like many theatres that have produced The Chinese Lady, InterAct found it attractive both as part of a mission to diversify their programming and their audiences, and as a COVID-conscious return from shutdown.

“As a two-hander, The Chinese Lady presented maximum reward, artistically, for minimal risk, in terms of the size of the company involved,” said Seth Rozin (he/him), InterAct’s artistic director. “It felt prudent to us to not test fate when it came to COVID exposure.”

For actor Bi Jean Ngo (she/her), who played Afong Moy at InterAct, the play offered a kind of healing.

“I think coming out of this time of social isolation, where we’ve just been talking through screens, and when the country and the world has been so partisan, so politically divisive, and there’s been so much hate, so much violent hostility, it was a really magical moment every night to stand there and be in true community with everyone,” Ngo said. At the end of the play, “The lights came up on the audience as I was saying these words, so we could all really look at each other and spend the last few moments of the play holding each other’s gaze, and holding each other in a greater sense of responsibility, human responsibility toward each other.”

“I have shared it with you in hopes that you might see what it means for the present, and how it might shape the future. I have shared it in the hope that you might recognize some part of it as your own.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

After the Public run, The Chinese Lady’s journey is far from over. The Kitchen Theatre Company in Ithaca, N.Y. will stage it March 22-April 10, and that same production will go to Geva Theatre Center in Rochester April 20-May 8. The last production on the books at presstime: The show’s Chicago premiere at TimeLine Theatre (May 8-Jun 18).

“We read The Chinese Lady soon after, or while it was playing at Milwaukee Rep., which is going back now a few years, and immediately fell in love with it,” said TimeLine artistic director PJ Powers (he/him). “Eight weeks before the COVID shutdown, we featured it in a one-night only reading in our Timepieces play reading series, and it blew us away, blew the audience away. The discussion afterwards was so vibrant, and we decided pretty quickly to to program it for what would have been our 2020-21 season. So it was scheduled to be done in spring of 2021.”

The pandemic forced them to postpone the production, so on May 13, 2021, the play’s intended opening night, TimeLine produced a live virtual program featuring excerpts from Chinese Lady, as well as a conversation among Suh, director Helen Young, and some experts in Chinese American history. “It was a way to both sort of keep the story and spirit of our production alive until we could finally do it, and it was also a way to provide some visibility to some AAPI organizations and lend some support,” said Powers.

The Chinese Lady wasn’t the only thing put on pause at TimeLine: The theatre was in the midst of a capital campaign to build a permanent home when the pandemic shut them down; in the four months leading up to March 2020, they had received $4 million. They retained their staff, despite some furloughs and salary adjustments.

“We tried to keep a commitment throughout the pandemic, whenever possible, to put money in the pockets of artists, because we just knew how much hurt there was,” Powers said. “Some of the virtual programs we did were a small way to put someone on a contract for a week or two, or put money in their pocket, or give them a week of health or pension.”

The stakes for their new home were raised when their building’s landlord sold the property. While TimeLine works on the permitting process for its new space, with hopes to begin construction this summer, the company opted to rent Theatre Wit as a venue for its spring productions, including The Chinese Lady.

“But if we take the time to really look at each other. To really look at each other. Then we might see, through all that vastness and variance, something true and real and wonderful.”

—“The Chinese Lady”

For Suh, having his play land at the Public after all this offstage drama is positively life-affirming.

“Oh, it feels extraordinary,” he said. “I mean, I almost can’t even put it into words. My first playwriting teacher was Dennis J. Reardon, who is a great writer and incredible teacher, and was one of Joseph Papp’s early playwrights. His play The Happiness Cage was the first play to ever be performed in the Newman. And so, even as a college undergrad, wondering about whether playwriting was for me, the Public Theater was a pretty iconic place in my mind. To be able to work there in conversation with all the writers who have done critical work there, especially in co-production with Ma-Yi, which has been my artistic home for almost the entirety of my professional life, is especially extraordinary.”

Though American history tried to erase Afong Moy, her story is now reaching audiences far and wide.

“It feels it’s all part of a journey,” said Ralph Peña. “I don’t think this is the end of the story for The Chinese Lady.”

Or for the Chinese lady herself. There’s no telling how far her story can go.

Alli Pierson (she/her) is associate editor of American Theatre. apierson@tcg.org