This is one in a series of stories marking the two-year anniversary of the COVID-19 shutdown. The full package is here.

At a time when the American theatre was facing perhaps its most difficult challenge yet—the COVID-19 pandemic—one Florida theatre saw a unique opportunity. Unable to produce live events, Florida Studio Theatre, the state’s largest subscription theatre, turned to one of FST’s core programs: new-play development. With the launch of its Playwrights Project, FST hired more than 30 of the nation’s top writers to develop new work for its five stages.

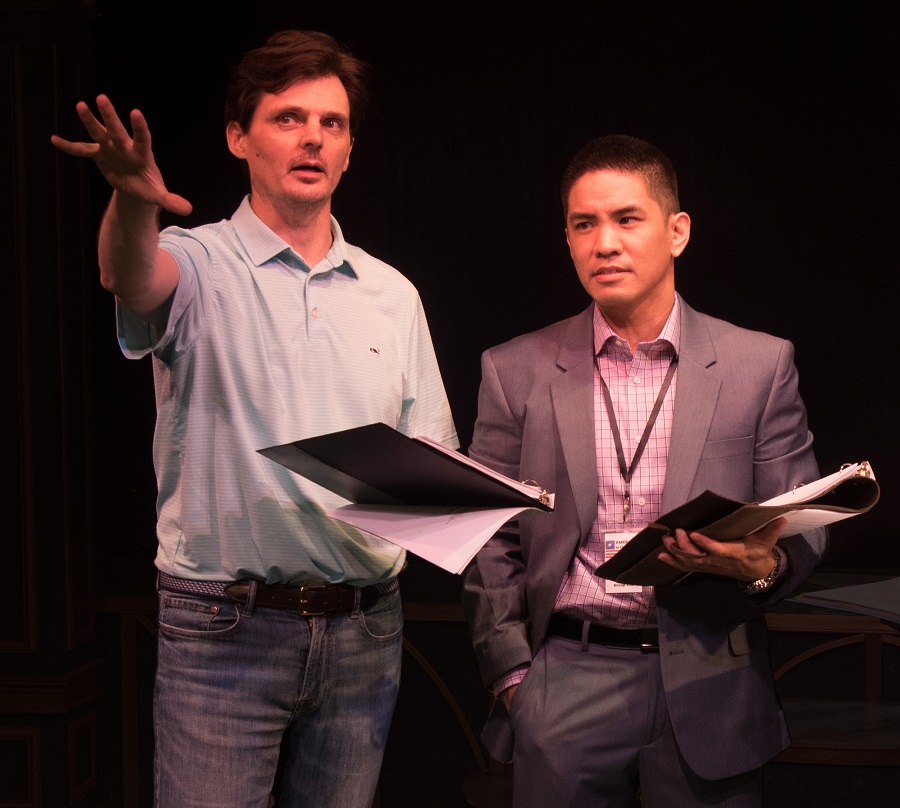

One of those plays, America in One Room by Jason Odell Williams, recently wrapped up its world premiere production at the same theatre that gave it birth. For Williams (he/him), a New York-based playwright and television producer, this opportunity could not have come at a better time. This is his story.

It was the faces that drew me in.

Five-hundred-plus photos splashed across several pages of The New York Times. Young faces. Old ones. All walks of life. From all over America.

I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the beginning of my next play.

The people in those photos had just been part of a radical experiment. Over 500 registered voters were invited to a Texas resort in late September 2019 to take part in a three-day conference to discuss some of America’s most pressing political issues: healthcare, immigration, the economy.

And while a play about strangers discussing politics might not seem like the obvious choice, I kept coming back to those faces. Who were these people? Why did they take time out of their lives to do this? Did they think it would make a difference in the world? Did it make a difference?

They called the event “America in One Room.” And for months that section of the newspaper sat on my desk, getting a little dusty, a little yellow with time. I was busy writing and producing for television, but still, I kept thinking that might have found my next play. The idea stuck with me. I’d think about it while walking the dog or running in Central Park. Maybe there’s something there? Eh, I’ll get to it eventually.

Before I knew it, five months had passed, and it was March 2020. Everything was shut down, and I was suddenly out of a job. Several planned productions of my plays were cancelled across the country. So writing a new one seemed pointless. But then I remembered a quote attributed to Carrie Fisher, one of my writing heroes: “Take your broken heart…make it into art.”

Yeah. I’ll definitely do that, Carrie—right after this next episode of Bojack Horseman.

Then came a phone call out of the blue. A life raft, really. Catherine Randazzo, Florida Studio Theatre’s literary manager, said that while live productions were shut down, they were going to use the time to develop new work, commissioning 20-30 plays from writers around the country. Did I have any ideas?

I dusted off that newspaper article and pitched on the fly. She loved it. A week later, I had been commissioned to write America in One Room. Richard Hopkins, FST’s producing artistic director, even told everyone in this new “Playwrights Project” not to self-edit or write more traditionally “producible” plays with smaller casts and production budgets. Instead, Richard said something not many theatre producers ever tell writers: He encouraged us to think big—to “blue sky it,” as they say. Write the biggest, boldest, most audacious thing we can think of, and they would figure out how to make it work. There were no promises for a production, or even a reading, but that didn’t matter. I had purpose again. A reason to get up and work and create each day.

As I dug into the idea, I researched the real-life event further and even did some internet sleuthing to track down some of the faces from the article. Many were kind enough to return my cold emails, and I spoke on the phone for over an hour each to four people who attended the America in One Room conference. They shared some remarkable insights—like how they nicknamed the event “A1R”—and how most of their breakout session group still stayed in touch via text chain. Two of these former strangers now considered each other close friends—and no, they don’t identify with the same political party.

That was the lightbulb moment and the central dilemma taken up by the play: Could strangers from across the political aisle find common ground, or, more importantly, at least find a way to treat each other with respect and dignity? The answer from the conference seemed to be a resounding “Yes.”

As I started to dig deeper and read more press coverage about the findings from the 2019 convention, it appeared that my hunch was right. Across the board, participants felt less animosity toward their fellow Americans and more connected to one another on a human level. They felt more hope for our country after the conference. Opinions shifted, eyes were opened, and a middle ground was found. Yet if you turn on cable news, that idea seems more far-fetched than colonizing Mars.

So maybe a play inspired by (and very loosely based on) this event could tackle the thorny questions about who we are as a nation and help show that, as cheesy as it sounds, there’s more that unites us than divides us, and there’s still good reason to have hope.

It took dozens of drafts—some really awful, terrible drafts. The cast size was 5, then 10, then 9. There was audience participation in the play, then none, then just a little bit. Was there too much talk about politics in the play? Not enough? How faithful to the real-life event did we need to be? (As it turns out, not very!)

The 2019 event provided a framework for balanced, respectful, and informed deliberations guided by a neutral moderator that purposely omitted hyper-partisan talking points. But that doesn’t make for great drama, so I needed to turn up the volume on the tensions and exaggerate some of the conflict that the original event was expressly designed to mitigate.

There were Zoom readings. So many Zoom readings. With a large cast and lots of overlapping dialogue, it was a major challenge to figure out what was working and what was not. Would it be better when we did it in person? Or was that section just a case of sloppy writing? I thought maybe I’d never find out.

In July came another amazing phone call from Catherine at FST. The theatre had been cleared to do in-person workshops and America in One Room was going to be one of them!

Fully vaccinated, my wife and I flew (for the first time in 18 months) to Sarasota. It was a whirlwind rehearsal process. We only had five days from the first read-through to the staged reading for the public. The cast was a mix of locals and out-of-towners. Some had been in the Zoom readings. Some were reading the play for the first time.

Script changes were made throughout the week, including a significant cut just a few hours before the public reading. When I finally sat in the packed house of about 150 patrons, all of us wearing masks, there was a buzz in the air. This was the first live performance I’d seen in nearly two years. Same for most of the folks around me. It was thrilling just being in a theatre again.

Oh yeah, and the play was a hit: laughs, tears, audience members talking back to the actors, chiming in, loving every minute. It was a real highlight of my theatrical life. I didn’t think it could get any better.

Then, four days later, yet another lovely phone call came from Catherine. Florida Studio Theatre had decided to present the full world-premiere production of America in One Room in their upcoming mainstage season. The play would run for 12 weeks. Nine actors, nine understudies. During COVID! No easy feat.

There were challenges and logistical hurdles, not to mention trying to get the script right. But somehow, with the unwavering support of FST, we pulled it off. Opening night was a hit. The audience responses were memorable. One patron named Valerie told me, “I wish everyone could see and think about this play,” and another named Kim called the show “excellent and thought-provoking.”

Another bit of feedback was especially meaningful. I heard from Valentin Bolotnyy, a fellow from Stanford’s Hoover Institute, who was one of the research collaborators behind the real America in One Room project, who had flown across the country to see the production. He wrote to me, “You captured the essence of the experiment really well; when we create the space and time to listen and actually get to know each other, to understand that each individual is not a stereotype but a complex and nuanced human being, to let our humanity shine through, better understanding, hope, and healing are possible. The play is a gift to America—it gets audiences thinking and reflecting on their own lives in ways that are crucial if we are to heal our social fabric.”

No spoilers here, but the play ends with a question for the onstage participants and the audience about whether they have hope for this country. Two years ago, I would have said, no way. But as corny as it sounds, after spending countless hours with this play and seeing how the real A1R participants learned to listen and respect each other’s opinions, I do have hope for this country after all.

As divided factions, we’re pretty stubborn. But as individuals, we’re open-minded, respectful, and genuinely decent. All it takes, it seems, is a little less time spent on social media or cable news, and a little more time talking and listening to people we may not agree with politically or socially.

In March 2020, if you would have told me that a play I hadn’t written yet would be playing to packed houses less than two years later while a pandemic was still going on, I’d have thought, “Everything you just said is crazy!” But that’s what happened. And it’s all thanks to a single New York Times article, the real-life America in One Room event, and a glorious phone call from Florida Studio Theatre.

And, of course, those faces. The faces of America.

Jason Odell Williams is a playwright and television producer. He lives in New York City with his wife and daughter.