This is one in a series of stories marking the two-year anniversary of the COVID-19 shutdown. The full package is here.

Coal Country began long before the first rehearsal. I had been invited by the Public Theater to do a workshop with Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen on their as yet “Untitled Upper Big Branch Mine Project” five or six years ago.

I was a huge fan of Erik and Jessica’s docutheatre work; Exonerated blew me away, followed up by their magnificent Aftermath. With this new project they were expanding their unique format to include the music of folk-country genius Steve Earle. He’d accompanied Erik and Jessica on the interviews, knew the families, and wrote songs based on their experiences.

They’d gather actors to read through mountains of transcripts of their interviews with the family members and survivors of the 2010 Upper Big Branch Mine disaster in West Virginia, a completely preventable tragedy caused by a gross prioritization of profit over human life, in which 29 coal miners were needlessly killed, and the CEO of the coal company did just 12 months of jail time. The survivors and families of those killed were left with nothing but raw, nagging grief.

Most productions that reach the stage are years in the making, but I’ve never been a witness to an evolution as complete as that of Coal Country. With each workshop, other actors and I watched as Jessica and Erik honed down what was essential for the story. They put a timeline of events on huge maps all over the rehearsal space, and they added and subtracted voices through much trial and error. We read through pages and pages of the actual trial.

I couldn’t participate in the final workshop, which was designed to incorporate Steve’s music, and thought, Well, I’ve kissed this one goodbye. When I ran into Jessica in August 2019, and she told me the Public would mount it in spring 2020, my heart sank that I wouldn’t be part of it, but I wished her much success with all the grace I could muster at the time. Then I got a call a week and half later asking me if I’d play Patti Stover. I literally fell to the floor.

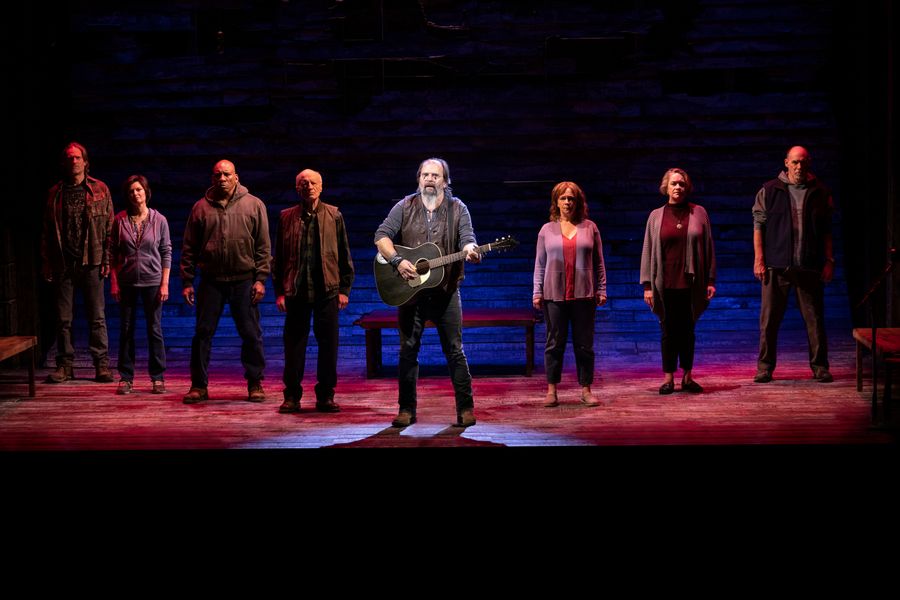

Despite my previous involvement, neither I nor any of the actors quite knew what this piece was going to be. Was it a play? A musical? Steve Earle would be right onstage telling the story with us through his songs and underscoring. We were playing real living people, who we were encouraged to inhabit with just their spoken words as our foundation. The project’s message felt more urgent than that of most plays; the three creators were very clear that they had been entrusted with these sacred stories, and owed an enormous duty to get them right, to do these 29 souls and their families the justice they hadn’t received.

The concise 90-minute narrative it became was potent and piercing, which we discovered as we began to perform it in early March of 2020. We couldn’t help but notice the palpable effect it had on those watching. To me it seemed that Coal Country had created a space for those witnessing its stories to get angry, to touch their own grief and humanity, and to connect to their inherent compassion. It was unlike anything I had ever done before.

We had two weeks of previews and opened on March 3. That weekend, the Public arranged for the people we were portraying to come from West Virginia to New York to see it. Aside from the wonder of seeing themselves onstage, they were uniformly stunned to see utter strangers in the audience care about what had happened to them; they didn’t think their stories could matter to anyone, especially not New Yorkers. We assured them that yes, every night, people cared—they cared so much they stayed after just to tell us so.

Three days later, the pandemic shut everything down.

Theatre cannot exist without an audience. It unites people’s spirits in one place, and I don’t care what religion you follow, it’s spiritual. That’s why it feels different than film or TV; a bunch of humans gather in the same space and focus on the same thing at the same time, breathing together. And yet COVID-19 made that kind of shared space the riskiest place to be, its means of transmission transmission reliant upon our proximity to each other and the very air we all share.

Two years later, now that we and the audience are safe to go back to the theatre, the Public and Audible have worked to bring it back (at the Cherry Lane Theatre through April 17); they feel the story still matters, and that it ought to have the life it was denied.

How does being back feel? I asked my castmates.

One said, “Bittersweet.” I agree. It’s been so sweet to come back to something we hadn’t fulfilled the promise of, but bitter, too; the shiny exhilaration we all felt during the first production has been indelibly marked by the last two years, with its huge loss of life, the lingering tension and terror and fear, the massive social upheaval in the U.S., and the collective exhaustion of all of it. I’ve been wary.

Then, during the third week of rehearsal, Erik Jensen had a medical emergency and was rushed to the hospital for surgery. And suddenly the fragile reality of life burst upon us. All through tech we watched Jessica run back and forth from the hospital to rehearsals. (Thankfully, Erik is okay now.) Whatever trepidation I had about committing to this show 100 percent again was replaced by the immediacy of the present moment—the urgency of making the most of this second chance for Erik and Jessica, for these families, for these miners, and for all those who have suffered similar fates. We need to try to get this right, right now, no matter what; even if we only play for a week, it will be one week longer than we played in 2020.

We shut down almost exactly two years to the day of when we will open (March 12, 2020, and, fingers crossed, tonight, March 10). I don’t think of two years in the same way I did before; this pandemic has played with time, sped it up and slowed it down, turned it inside out. I read a recent commentary in The New York Times on an W. H. Auden poem about suffering; the commentator had read it years before. She noted how it resonated more profoundly now—that her lived experience made the poem mean more to her. A castmate said the same thing happens with Coal Country; those watching give it significance through their lived experience. I think that aptly describes how it feels to be back. My lived experience over these past two years has deepened its resonance for me, heightened even more its necessary universal truths, and its lessons for humanity. Simply that. It has that power.

To be returning from this pandemic’s isolation, in this New York theatre community, with this show, this particular story, is helping me understand and make sense of the past two years. Just as it helps those who watch it make sense of their own grief, sorrow, and joy. And hopefully, help us all commit to changing how we operate in this world, that we might engage with compassion, as we come into relation with each other again. That’s how I feel. Grateful. Honored. Delighted. Blessed. To be a part of Coal Country again.

Mary Bacon won the 2020 Drama Desk Award for her performance in Coal Country and for her New York theatre career.