Director and teacher Andrei Belgrader died on Feb. 22. He was 75.

Andrei the Great.

I met Andrei Belgrader in 1980 as a first-year student at Yale Drama School. He was walking with his shoulder bag slung over his shoulder, black vest on over a T-shirt, wearing a baseball hat and smoking his cigarette in a black plastic holder. He looked different than the other teachers. And he was.

The Beckett quote, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better,” was something Andrei embodied.

I remember being in his third-year acting class and his making us do an exercise—we had to get up in front of the whole group, walk back and forth, and pick a body part we thought was exceptional and sort of riff on it. I picked my eyes, I said, “My eyes are like Elizabeth Taylor’s,” and then built on it from there, parading before the class, and blurting out how people I looked at collapsed, overcome with the mesmerizing beauty of them. There was Andrei lying on his side like a big cat, lit cigarette in hand, howling with laughter. Which of course made you braver and freer and made you go further into the ridiculous and beyond. The relaxing, imaginative, play-room atmosphere he created made the class completely different from our other classes and not at all competitive. He was a breath of fresh air, interested in who we were and what we could create.

He was unafraid of taking time. When I did Waiting for Godot with Tony Shalhoub, Christopher Lloyd, and the one and only Richard Spore, he asked my eight-year-old, Amedeo, to be in the play. He thought there was something about Amedeo that was right for Beckett and that she was something of a philosopher, and, of course, he was right about that.

In the opening of the play, he wanted me as Estragon to struggle to take off my shoe. I struggled, but he wanted me to make it harder, and then harder, and even harder, until it was taking two, three minutes, and he was saying, “No, you should take even longer.” I was pretty limber and I managed to get myself into all those different contortions with my hands, with my legs and my feet over my head. It became a whole routine—it must have taken four minutes or something, and the longer it took and the longer I struggled without having the shoe fall off, the funnier it was. That was all Andrei: pushing you to have the courage to go far beyond your self-consciousness and finding freedom in the task at hand.

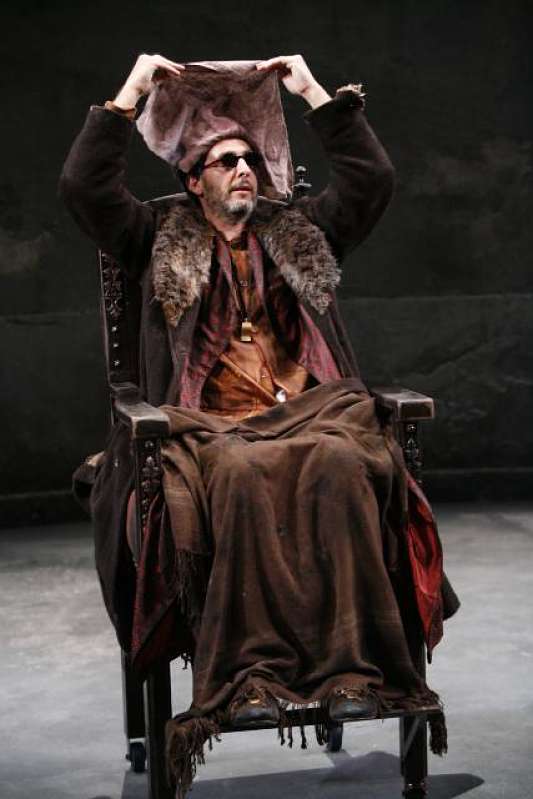

He did the same thing when we did Endgame. One of the first lines of Hamm is, “Can there be misery loftier than mine?”, with a yawn indicated in the middle of the line. He wanted me to not do the yawn there but to “puff myself up like a balloon,” because there could be no one in the world who could suffer the way I suffered as Hamm. He pushed and cajoled and challenged me some more to set the tone immediately. Fifteen years later, I’m still working on that one line, still searching.

One day after a Saturday matinee, Edward Albee came back to our dressing rooms and he was so delighted. He said, “You got the cruelty and the humor—you got both!” That was Andrei. He always used to tell us: “Don’t try to be good.” And I would ask, “What do you mean by that?” “Don’t try to be good, just be.”

He would be pushing you to unbelievable imaginative extremes, but not for a result, never. He was pushing you to reach beyond yourself. When things would come together, eventually, they would happen in an organic way that grew as time went on.

The same thing happened in The Cherry Orchard. In rehearsals there were many people in the cast who said, “I don’t know what I’m doing, this is terrible.” They were in tears, and I would say, “We’ll get there, Andrei has his own approach to doing things.”

He wanted me to do this big crazy Russian dance as Lopakhin after I did “The cherry orchard is mine…” speech. He wanted me to do the high kicks, slaps and all, “like you almost want to make a hole in the floor and break it,” he told me. He kept pushing and encouraging me to go further. I figured out the choreography, but not hurting myself was a big challenge, and sometimes I gave myself a big headache by doing all those high kicks and stomps. He wanted it to be this kind of primitive dance of exultation over the ruling class. And it became just that—Andrei’s dance of defiance.

In the proposal scene that I did with Juliet Rylance, he said, “You can kneel, you can try to say the words, but you don’t have to speak, you can take as long as you want,” and we did, until we were both bursting at the seams and it became almost like a real-life impossible proposal, with neither one of us able to say the words, never able to get them out. Andrei dared you to be brave.

He knew about leaving home. The Cherry Orchard is about leaving your home, and he never talked about it: escaping Soviet-controlled Romania under the dictatorship of Ceaușescu, or that he was Jewish and that he lost his extended family in the Holocaust—he never talked about it. He was a man who valued freedom above all. He knew what it meant to not be able to express yourself.

The joy he got when you took off! The delight! The patience that you would get there, somewhere that you had never imagined. He believed you could do anything. Planning a workshop of Ubu Rock, an infamous production he did at the ART, he wanted me to be Ubu. I told him, “You know I’m not really a rock ‘n’ roll singer.” He said, “I think you are; I think there’s an inner Elvis Presley in you.” And there was! There is!

Andrei…How much I will miss him. I am only one of many. I cannot imagine not going on another impossible adventure with Andrei again. I know I will carry him inside me always. The way he looked at you and appreciated you, he didn’t have to say, “I love you”, you knew it. It was silent. He was very shy that way, but you knew; you felt his belief, even when you failed. He was always looking for your inner genius. He made you feel like maybe, perhaps, you had one.

“Blessed be” was how he always said goodbye.

Blessed be, my dear friend.

John Turturro (he/him) is an actor, director, writer, and producer.

Creative credits for productions: Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett, directed by Andrei Belgrader, with set design by Andrei Both, costume design by Elizabeth Hope Clancy, and lighting design by Michael Chybowski; Endgame by Samuel Beckett, directed by Andrei Belgrader, with costume design by Candice Donnelly, lighting design by Michael Chybowski, and set design/decor by Anita Stewart