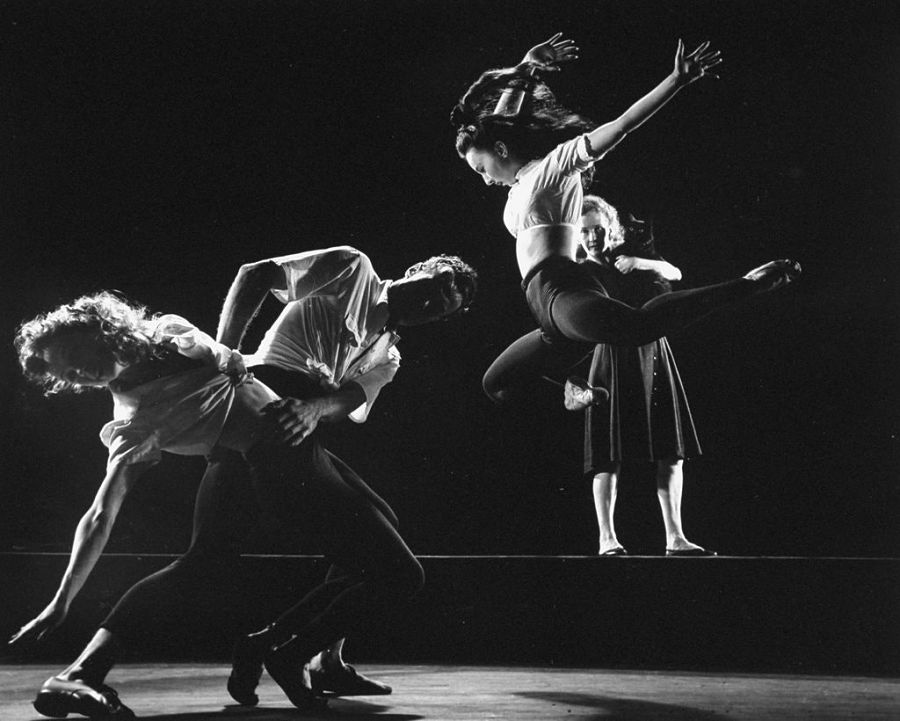

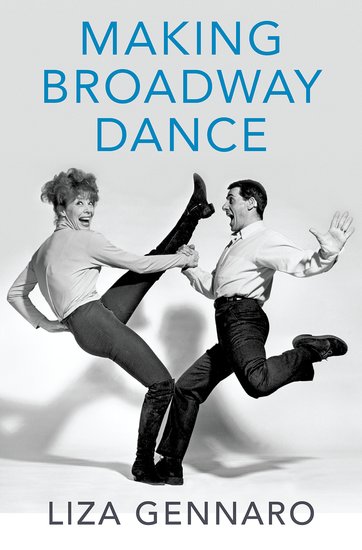

With many theatres still suffering pandemic-induced shutdowns, fans of big, dance-filled Broadway musicals have few opportunites to partake of the real thing. But Broadway dance devotees can imbibe vicariously, thanks to two new books from Oxford University Press, filled with intoxicating descriptions of musical theatre choreography. The disjointedly written Making Broadway Dance by Liza Gennaro (daughter of famed Broadway dancer and choreographer Peter Gennaro, and a theatrical choreographer in her own right) proffers smartly analytical passages spotlighting iconic Broadway dances of the past. Not a how-to book for aspiring choreographers, the verb in its title might more properly be “watching” or “interpreting,” as it takes an observational perspective, putting forth illuminating lenses through which to view dances already made.

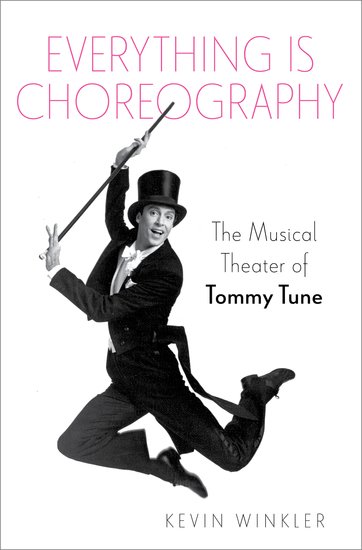

Kevin Winkler, on the other hand, in his Everything Is Choreography: The Musical Theater of Tommy Tune, takes us behind the scenes and into the rehearsal room with the eponymous Broadway director-choreographer, and documents the complicated journeys and processes involved in the creation and mounting of hit Tune-helmed tuners.

Winkler’s book isn’t a biography, thoroughly investigating Tune’s career yet supplying little information about his personal life. (For that, you have to read Tune’s own 1997 book, Footnotes, a wily memoir that proves more provocative than revelatory.) Arguing that Tune is the last in Broadway’s lineage of star director-choreographers (the others being Agnes de Mille, Jerome Robbins, Bob Fosse, Gower Champion, and Michael Bennett), Winkler claims that Tune kept the American musical thriving during the 1980s when Broadway, dominated by British imports, was at a low point—and that Tune did so by looking backward. Eschewing the pageantry and wow-worthy technological effects embraced by the creators of the era’s mega-musicals, Tune instead mined the unique talents of star performers and reimagined old-fashioned dance styles: tap, ballroom, precision chorus lines, vaudeville specialties, and titillating Ziegfeld-esque tableaux.

Winkler supports his point with vivid descriptions of the staging of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1978), A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the Ukraine (1980), Nine (1982), My One and Only (1983), Grand Hotel (1989), and The Will Rogers Follies (1991), all of which Tune singly or collaboratively directed and choreographed. Unlike the dry, wordy dance descriptions, over-stuffed with pointless details, that bogged down Big Deal, Winkler’s 2018 book on Bob Fosse, the descriptive writing here is lively, accessible, streamlined, and image-packed. We really sense the energy, rhythms, moods, and sounds of the movements, and are able to feel the theatricality of the choreography, and, hence, understand how Tune’s staging worked to drive the drama in his productions.

Yet in order to accept the author’s inclusion of Tune among Broadway’s director-choreographer greats, one needs to separate the two roles and understand that Tune’s membership in the club is based on his extraordinary talents as a director, and his ability to conceive the overall staging of a show and communicate all of its essential dramatic points visually and through movement, be they technical dance moves or more pedestrian body postures, gestures, or actions. It’s harder to consider Tune a great choreographer, as his dances are not notable in terms of invention, and, as we learn from Winkler, he often delegated the devising of steps to his assistants, preferring to keep his focus on the show’s larger movement picture.

Because Winkler discusses Tune’s work in terms of the various elements of a musical, and in the context of what else was happening at the time on Broadway—and in American politics, which I would argue is reflected in any interpretive discussion of a musical—his book will appeal to everyone with a bent for musical theatre, even those with no particular interest in choreography.

The same cannot be said for Gennaro’s book, which may be a tough slog for readers lacking a solid dance background. As I myself am enamored with the study of musical theatre dance, I was predisposed to delight in reading Making Broadway Dance, especially considering how in sync Gennaro’s perspectives on the topic are with my own. For example, in her dissections of Broadway choreography, she always begins with a dramaturgical lens, showing how dance functions to convey a musical’s dramatic ideas; similarly, I began my research into musical theatre dance by writing a doctoral dissertation focused on the dramatic functions of dance in 1960s Broadway choreography.

Moreover, the first choreographer Gennaro singles out for lengthy discussion in her book is Agnes de Mille. She devotes one chapter to unearthing the modernist influences on de Mille’s choreography for Oklahoma! (1943), and another to applying a feminist lens to de Mille’s dances for One Touch of Venus (1943), Bloomer Girl (1944), and Carousel (1945). Likewise, my first journal article—published 32 years ago, when very few dance scholars were writing about Broadway—was titled “The Influence of Modern Dance on American Musical Theatre Choreography of the 1940s,” while the first scholarly conference paper I presented was “The Portrayal of Women in the American Musical Theatre Choreography of Agnes de Mille.”

Yet despite my kinship for its content, I found reading Gennaro’s book more frustrating than fun. Unlike Winkler, whose contextualizing of Tune’s work doesn’t stray beyond Broadway musicals and the cultural issues reflected therein, Gennaro attempts to situate musical theatre choreography within the larger history of dance in America. Her book’s primary mission is to demonstrate how the making of Broadway choreography constitutes an artistic dance practice, and that it should be recognized as such, not written about dismissively, as it still often is in scholarly circles. Hence her work is targeted to an academic audience, not to Broadway buffs. She goes to great lengths to surround her descriptions of a selection of exemplary Broadway dances (largely by de Mille, Robbins, Champion, Fosse, and Bennett) with explanations of everything else that was going on in the American dance world. But she doesn’t connect the dots for us. Consequently, we read many short, fact-packed paragraphs on discrete, superficially treated topics and don’t know what to make of the abundance of unrelated information. For those new to dance, it’s too much to absorb, and for connoisseurs, it’s unnecessary.

That said, despite its disorganization, Gennaro’s book contains some of the best academic writing about musical theatre dance I have ever read. My big concern is that Broadway dance fans may be put off from persevering through her worthy treatise because of its reader-unfriendly tone and presentation. Is it really necessary to clutter the text with both bottom-of-the-page footnotes and parenthetical citations? To include bibliographies of both print and video resources at the end of every chapter? And why cite the exact same source in six separate parenthetical references within a single paragraph?

Here’s what I recommend, readers: Start in the middle of the book. Skip the messy first chapter, which reads like a rough draft of a graduate school research paper, and go right to the center of Chapter 2, where Gennaro writes an exquisite blow-by-blow description of Oklahoma!’s famous dream ballet, insightfully comparing a duet portion of it to the similar “Puritan Love Duet” from American Document (1938), a work by modern dance genius Martha Graham, de Mille’s revered, influential friend. Read Chapter 3’s wonderfully interpretive descriptions of One Touch of Venus’s “Forty Minutes for Lunch” and “Venus in Ozone Heights,” and Bloomer Girl’s Civil War ballet, all of which contain illuminating historical references to folk and concert dance.

Then indulge in the next two chapters on Jerome Robbins, where you’ll gain a rich understanding of how he surpassed de Mille in his dramaturgical employment of Broadway dance. You’ll also be treated to Gennaro’s explication, undoubtedly drawn from her practical experience, of some concise choreographic advice Robbins once gave to Fosse. Additionally, Gennaro provides valuable clarification of the contributions her father made as co-choreographer of West Side Story, the dances for which are commonly credited to Robbins alone.

In the book’s final two chapters, Gennaro meanders through the shifting terrain of Broadway dance over the last 60 years or so. Those chapters’ highlights are her keenly detailed deep dives into Fosse’s “Big Spender” from Sweet Charity (1966), Champion’s “Shriner’s Ballet” from Bye Bye Birdie (1960), and Bennett’s “Always Mademoiselle” from Coco (1969). Culminating with discussions of the impact of the AIDS epidemic, gender discrimination faced by women director-choreographers, and post-modern and physical theatre-influenced innovations brought by 21st-century Broadway dance-makers, Gennaro’s book will reward intellectual readers willing to forge meanings themselves out of the wealth of disparate information served up by the author. While Winkler gives us Tune on a silver platter, Gennaro makes us dance for our supper.

Lisa Jo Sagolla (she/her), a New York-based arts critic, is the author of The Girl Who Fell Down: A Biography of Joan McCracken” and Rock ‘n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s. She teaches at Columbia University’s Teachers College and Rutgers University, and is currently researching a chapter on the Broadway musical Timbuktu! for a new book on Geoffrey Holder.